Renewable energy in Australia

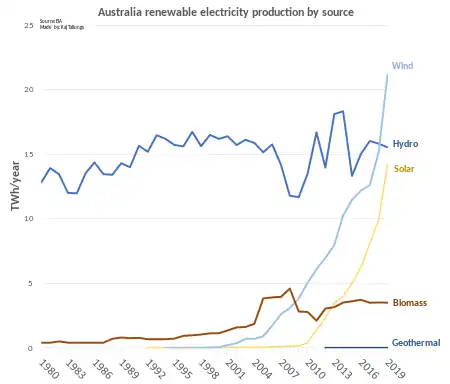

Renewable energy in Australia includes wind power, hydroelectricity, solar photovoltaics, heat pumps, geothermal, wave and solar thermal energy.

| Source | Generation (GWh) |

|---|---|

| Wind | 29,892 |

| Small solar | 21,726 |

| Hydro | 16,537 |

| Large solar | 11,740 |

| Bioenergy | 3,181 |

| Medium solar | 980 |

In 2022, Australia produced 84,056 gigawatt-hours of renewable energy, which accounted for 35.9% of electricity production.[1]

Australia produced 378.7 PJ of overall renewable energy (including renewable electricity) in 2016-17, which accounted for 6.2% of Australia's total energy use (6,146 PJ).[2] Renewable energy grew by an annual average of 3.2% in the 10 years between 2007 and 2017, and by 5.2% between 2016 and 2017. This contrasts to growth in coal (-1.9%), oil (1.7%) and gas (2.9%) over the same 10-year period.[2]

Similar to many other countries, development of renewable energy in Australia has been encouraged by government energy policy implemented in response to concerns about climate change, energy independence and economic stimulus.[3][4][5]

Renewable energy by fuel type

| Renewable fuel type | 2016–17 (PJ)[2] | 2020–21 (PJ)[6] | Change (%) | Share of renewables 2020–21 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass | 205.4 | 171.2 | −16.7 | 37.0 |

| Municipal and Industrial waste | 2.6 | 4.6 | 76.9 | 1.0 |

| Biogas | 15.0 | 18.0 | 20.0 | 3.9 |

| Biofuels | 7.1 | 6.2 | −12.7 | 1.3 |

| Hydro | 58.6 | 54.7 | −6.7 | 11.8 |

| Wind | 45.3 | 88.3 | 94.9 | 19.1 |

| Solar PV | 29.1 | 99.8 | 243.0 | 21.6 |

| Solar hot water | 15.7 | 19.7 | 25.5 | 4.3 |

| Total | 378.7 | 462.4 | 22.1 | 100.0 |

Timeline of developments

- 2001

A mandatory renewable energy target is introduced to encourage large-scale renewable energy development.

2007

Several reports have discussed the possibility of Australia setting a renewable energy target of 25% by 2020.[7][8] Combined with some basic energy efficiency measures, such a target could deliver 15,000 MW new renewable power capacity, $33 billion in new investment, 16,600 new jobs, and 69 million tonnes reduction in electricity sector greenhouse gas emissions.[8]

- 2008

Greenpeace released a report in 2008 called "Energy [r]evolution: A Sustainable Energy Australia Outlook", detailing how Australia could produce 40% of its energy through renewable energy by 2020 and completely phase out coal-fired power by 2030 without any job losses.[9] David Spratt and Phillip Sutton argue in their book Climate Code Red that Australia needs to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions down to zero as quickly as possible so that carbon dioxide can be drawn down from the atmosphere and greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced to less than 325 ppm CO2-e, which they argue is the upper "safe climate" level at which we can continue developing infinitely. They outline a plan of action which would accomplish this.[10]

- 2010

Mandatory renewable energy target was increased to 41,000 gigawatt-hours of renewable generation from power stations. This was subsequently reduced to 33,000 gigawatt-hours by the Abbott government, in a compromise agreed to by the Labor opposition.[11] Alongside this there is the Small-Scale Renewable Energy Scheme, an uncapped scheme to support rooftop solar power and solar hot water[12] and several State schemes providing feed-in tariffs to encourage photovoltaics.

ZCA launch their "Stationary Energy Plan"[13] showing Australia could entirely transition to renewable energy within a decade by building 12 very large scale solar power plants (3500 MW each), which would provide 60% of electricity used, and 6500 7.5 MW wind turbines, which would supply most of the remaining 40%, along with other changes. The transition would cost A$370 billion or about $8/household/week over a decade to create a renewable energy infrastructure that would last a minimum of 30 to 40 years.[14]

- 2012

In 2012, these policies were supplemented by a carbon price and a 10 billion-dollar fund to finance renewable energy projects,[15] although these initiatives were later withdrawn by the Abbott government.[16]

Of all renewable electrical sources in 2012, hydroelectricity represented 57.8%, wind 26%, bioenergy 8.1%, solar PV 8%, large-scale solar 0.147%, geothermal 0.002% and marine 0.001%; additionally, solar hot water heating was estimated to replace a further 2,422 GWh of electrical generation.[17]

- 2015

The Australian Government ordered the $10 billion Clean Energy Finance Corporation to refrain from any new investment in wind power projects, saying that the government prefers the corporation to invest in researching new technologies rather than the "mature" wind turbine sector.[18]

- 2017

An unprecedented 39 projects, both solar and wind, with a combined capacity of 3,895 MW, are either under construction, constructed or would start construction in 2017 having reached financial closure. Capacity addition based on renewable energy sources is expected to increase substantially in 2017 with over 49 projects either under construction, constructed or which have secured funding and will go to construction.[19] As of August 2017, it was estimated that Australia generated enough to power 70% of the country's households, and once additional wind and solar projects were complete at the end of the year, enough energy would be generated to power 90% of the country's homes.[20]

2019

In 2019, Australia met its 2020 renewable energy target of 23.5% and 33 terawatt-hours (TWh).[21]

2020

With the 2020 targets being achieved, many of the Australian states and territories committed to a greater 40% target for renewable energy sources by 2030, including Queensland, Victoria and the Northern Territory.[22]

- 2022

In July 2022, a report published by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering estimated that Australia would be generating around 50 per cent its electricity needs from renewable sources by 2025, rising to 69 per cent by 2030. By 2050, power networks would be able to use 100 per cent green energy for periods. However the report said that investment was also needed, not only in new renewable sources, but in services needed during the transition period – hydroelectric power, batteries and probably gas for a while.[23]

Hydro power

In 2022, hydro power supplied 19.7% of Australia's renewable electricity generation or 7.1% of Australia's total electricity generation.[1]

The largest hydro power system in Australia is the Snowy Mountains Scheme constructed between 1949 and 1974, which consists of 16 major dams and 7 major power stations, and has a total generating capacity of 3,800 MW. The scheme generates on average 4,500 GWh electricity per year.[24] A major extension of the scheme is ongoing as of 2020. Dubbed Snowy 2.0, it consists in adding a 2,000 MW pumped hydro storage capacity by connecting two existing reservoirs with tunnels and an underground power station. It is due to complete by 2026.[25]

Hydro Tasmania operates 30 power stations and 15 dams, with a total generating capacity of 2,600 MW, and generates an average of 9,000 GWh of electricity per year.[26] There are also plans to upgrade Tasmania's hydro power system to give it the capability to function as pumped hydro storage under the 'Battery of the Nation' initiative.[27]

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation (GWh) | 19243 | 14555 | 14046 | 17747 | 12920 | 17002 | 14166 | 14638 | 16128 | 16537 |

| % of Renewable Electricity | 55.4 | 45.9 | 40.1 | 42.3 | 33.9 | 35.2 | 25.7 | 23.3 | 21.6 | 19.7 |

| % of Total Electricity | 8.2 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 7.1 |

Wind power

In 2022, wind power supplied around 35.6% of Australia's renewable electricity and around 12.8% of Australia's total electricity.[1] Eight new wind farms were commissioned in 2022 with a combined capacity of 1,410 MW, bringing the total installed capacity to more than 10.5 GW. As of the end of 2022, 19 wind farms with a combined capacity of 4.7 GW were either under construction or financial committed nationally.[1]

Wind power in Victoria is the most developed with 8,655 GWh generated in 2021, followed by South Australia with 5,408 GWh, New South Wales with 5,384 GWh, Western Australia with 3,407 GWh, Tasmania with 1,859 GWh, and Queensland with 1,772 GWh.[35]

The largest wind farm in Australia is the Stockyard Hill Wind Farm , which opened in 2022 with a capacity of 530 MW. This overtook the 453 MW Coopers Gap Wind Farm.[35][1]

| Rank | Name | Capacity (MW) | Commissioned |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stockyard Hill Wind Farm | 532 | 2022 |

| 2 | Coopers Gap Wind Farm | 453 | 2021 |

| 3 | Macarthur Wind Farm | 420 | 2012 |

| 4 | Dundonnell Wind Farm | 336 | 2021 |

| 5 | Moorabool Wind Farm | 321 | 2022 |

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation (GWh) | 9259 | 9777 | 11802 | 12903 | 12873 | 16171 | 19487 | 22605 | 26804 | 29892 |

| % of Renewable Electricity | 26.6 | 30.9 | 33.7 | 30.8 | 33.8 | 33.5 | 35.4 | 35.9 | 35.9 | 35.6 |

| % of Total Electricity | 3.9 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 12.8 |

Solar photovoltaics

In 2022, solar power supplied around 41.0% of Australia's renewable electricity and around 14.7% of Australia's total electricity.[1] Twelve new large-scale (>5 MW) solar farms were commissioned in 2021 with a combined capacity of 840 MW, bringing the total installed large-scale capacity to almost 6.5 GW. As of the end of 2022, 48 large-scale solar farms were either under construction or financial committed nationally.[1]

Small-scale solar power (<100 kW) is the dominant contributor to Australia's overall solar electricity production as of 2022, producing 63% of solar's total electricity output (21,726 GWh of 34,446 GWh total).[1] In 2022, 2.7 GW of new small-scale capacity was installed across 310,352 installations, bringing total small-scale capacity to 19.39 GW.[1]

As of December 2022, Australia's over 3.36 million solar PV installations had a combined capacity of 29,683 MW of which 3,922 MW were installed in the preceding 12 months.[36]

| Rank | Name | Capacity (MW) | Commissioned |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Darlington Point Solar Farm | 275 | 2021 |

| 2 | Limondale Solar Farm | 220 | 2021 |

| 3 | Kiamal solar farm | 200 | 2021 |

| 4 | Sunraysia Solar Farm | 200 | 2021 |

| 5 | Wellington Solar Farm | 174 | 2021 |

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation (GWh) | 3820 | 4952 | 5931 | 7659 | 8615 | 11694 | 18126 | 22510 | 28561 | 34446 |

| % of Renewable Electricity | 11.0 | 15.6 | 16.9 | 18.3 | 22.6 | 24.2 | 32.9 | 35.8 | 38.3 | 41.0 |

| % of Total Electricity | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 9.9 | 12.4 | 14.7 |

Solar thermal energy

Solar water heating

Australia has developed world leading solar thermal technologies, but with only very low levels of actual use. Domestic solar water heating is the most common solar thermal technology.[37] During the 1950s, Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) carried out world leading research into flat plate solar water heaters. A solar water heater manufacturing industry was subsequently established in Australia and a large proportion of the manufactured product was exported. Four of the original companies are still in business and the manufacturing base has now expanded to 24 companies. Despite an excellent solar resource, the penetration of solar water heaters in the Australian domestic market was only about 5% in 2006, with new dwellings accounting for most sales.[38] By 2014, around 14% of Australian households had solar hot water installed[39] It is estimated that by installing a solar hot water system, it could reduce a family's CO2 emissions up to 3 tonnes per year while saving up to 80% of the energy costs for water heating.[40]

While solar water heating saves a significant amount of energy, they are generally omitted from measures of renewable energy production as they do not actually produce electricity. Based on the installed base in Australia as of October 2010, it was calculated that solar hot water units would account for about 7.4% of clean energy production if they were included in the overall figures.[41]

Solar thermal power

CSIRO's National Solar Energy Centre in Newcastle, NSW houses a 500 kW (thermal) and a 1.5 MW (thermal) solar central receiver system, which are used as research and development facilities.[42][43]

The Australian National University (ANU) has worked on dish concentrator systems since the early 1970s and early work lead to the construction of the White Cliffs Solar Power Station. In 1994, the first 'Big Dish' 400 m2 solar concentrator was completed on the ANU campus. In 2005, Wizard Power Pty Ltd was established to commercialise the Big Dish technology to deployment.[44] Wizard Power has built and demonstrated the 500m2 commercial Big Dish design in Canberra and the Whyalla SolarOasis[45] will be the first commercial implementation of the technology, using 300 Wizard Power Big Dish solar thermal concentrators to deliver a 40MWe solar thermal power plant.[46] Construction is expected to commence in mid-late 2013.

Research activities at the University of Sydney and University of New South Wales have spun off into Solar Heat and Power (now Areva Solar), which was building a major project at Liddell Power Station in the Hunter Valley. The CSIRO Division of Energy Technology has opened a major solar energy centre in Newcastle that has a tower system purchased from Solar Heat and Power and a prototype trough concentrator array developed in collaboration with the ANU.[44]

Geothermal energy

In Australia, geothermal energy is a natural resource which is not widely used as a form of energy. However, there are known and potential locations near the centre of the country in which geothermal activity is detectable. Exploratory geothermal wells have been drilled to test for the presence of high temperature geothermal activity and such high levels were detected. As a result, projects will eventuate in the coming years and more exploration is expected at potential locations.

South Australia has been described as "Australia's hot rock haven" and this emissions free and renewable energy form could provide an estimated 6.8% of Australia's base load power needs by 2030.[47] According to an estimate by the Centre for International Economics, Australia has enough geothermal energy to contribute electricity for 450 years.[48]

There are currently 19 companies Australia-wide spending A$654 million in exploration programmes in 141 areas. In South Australia, which is expected to dominate the sector's growth, 12 companies have already applied for 116 areas and can be expected to invest A$524 million (US$435 M) in their projects by the next six years. Ten projects are expected to achieve successful exploration and heat flows, by 2010, with at least three power generation demonstration projects coming on stream by 2012.[47] A geothermal power plant is generating 80 kW of electricity at Birdsville, in southwest Queensland.[49]

Wave power

Several projects for harvesting the power of the ocean are under development:

- Oceanlinx is trialling a wave energy system at Port Kembla.

- Carnegie Corp of Western Australia is refining a method of using energy captured from passing waves, CETO to generate high-pressure sea water. This is piped onshore to drive a turbine and to create desalinated water. A series of large buoys is tethered to piston pumps anchored in waters 15 to 50 metres (49 to 164 ft) deep. The rise and fall of passing waves drives the pumps, generating water pressures of up to 1,000 pounds per square inch (psi). The company is looking to have a 100MW demonstration project finished within the next four years.

- BioPower Systems is developing its bioWAVE system anchored to the seabed that would generate electricity through the movement of buoyant blades as waves pass, in a swaying motion similar to the way sea plants, such as kelp, move. It expects to complete pilot wave and tidal projects off northern Tasmania this year.[50]

Bio-energy

Biomass

Biomass can be used directly for electricity generation, for example by burning sugar cane waste (bagasse) as a fuel for thermal power generation in sugar mills. It can also be used to produce steam for industrial uses, cooking and heating. It can also be converted into a liquid or gaseous biofuel.[51] In 2015 Bagasse accounted for 26.1% (90.2PJ) of Australia's renewable energy consumption, while wood and wood waste for another 26.9% (92.9PJ).[52] Biomass for energy production was the subject of a federal government report in 2004.[53]

Biofuels

Biofuels produced from food crops have become controversial as food prices increased significantly in mid-2008, leading to increased concerns about food vs fuel. Ethanol fuel in Australia can be produced from sugarcane or grains and there are currently three commercial producers of fuel ethanol in Australia, all on the east coast. Legislation imposes a 10% cap on the concentration of fuel ethanol blends. Blends of 90% unleaded petrol and 10% fuel ethanol are commonly referred to as E10,[54] which is mainly available through service stations operating under the BP, Caltex, Shell, and United brands. In partnership with the Queensland Government, the Canegrowers organisation launched a regional billboard campaign in March 2007 to promote the renewable fuels industry. Over 100 million litres of the new BP Unleaded with renewable ethanol has now been sold to Queensland motorists.[54] Biodiesel produced from oilseed crops or recycled cooking oil may be a better prospect than ethanol, given the nation's heavy reliance on road transport, and the growing popularity of fuel-efficient diesel cars.[55] Australian cities are some of the most car-dependent cities in the world,[56] and legislations involving vehicle pollution within the country are considered relatively lax.[57]

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation (GWh) | 2400 | 2400 | 3200 | 3608 | 3713 | 3412 | 3314 | 3164 | 3187 | 3181 |

| % of Renewable Electricity | 6.9 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| % of Total Electricity | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.34 | 1.49 | 1.65 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

Government policy

Australia has implemented schemes to start the transition to a low-carbon economy but carbon neutrality has not been mentioned and since the introduction of the schemes, emissions have increased. The Second Rudd government pledged to lower emissions by 5–15%. In 2001, The Howard government introduced a Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET) scheme. In 2007, the Government revised the MRET – 20 per cent of Australia's electricity supply to come from renewable energy sources by 2020. Renewable energy sources provide 8–10% of the nation's energy, and this figure will increase significantly in the coming years. However coal dependence and exporting conflicts with the concept of Australia as a low-carbon economy. Carbon-neutral businesses have received no incentive; they have voluntarily done so. Carbon offset companies offer assessments based on lifecycle impacts to businesses that seek carbon neutrality. In Australia the only true certified carbon neutral scheme is the Australian government's National Carbon Offset Standard (NCOS) which includes a mandatory independent audit. Three of the four of Australia's top banks are now certified under this scheme. Businesses are now moving from unaccredited schemes such as noco2 and transitioning to NCOS as the only one that is externally audited. Most of leading carbon management companies have also aligned with NCOS such as Net Balance, Pangolin Associates (who themselves are independently certified under NCOS), Energetics and the Big Four accounting firms.

In 2011 the Gillard government introduced a price on carbon dioxide emissions for businesses. Although often characterised as a tax, it lacked the revenue-raising nature of a true tax. In 2013, on the election of the Abbott government, immediate legislative steps were taken to repeal the so-called carbon tax. The price on carbon was repealed on 17 July 2014 by an act of parliament. As it stands Australia currently has no mechanism to deal with climate change.

Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)

ARENA was established by the Australian Government on 1 July 2012. The purpose of ARENA is to improve the competitiveness of renewable energy technologies and increase the supply of renewable energy through innovation that benefits Australian consumers and businesses. Since 2012, ARENA has supported 566 projects with $1.63 billion in grant funding, unlocking a total investment of almost $6.69 billion in Australia's renewable energy industry.[58]

Renewable energy targets

A key policy encouraging the development of renewable energy in Australia are the mandatory renewable energy targets (MRET) set by both Commonwealth and State governments. In 2001, the Howard government introduced a 2010 MRET of 9,500 GWh of new renewable energy generation.

An Expanded Renewable Energy Target was passed with broad support[59] by the Australian Parliament on 20 August 2009, to ensure that renewable energy achieves a 20% share of electricity supply in Australia by 2020. To ensure this the Federal Government committed to increasing the 2020 MRET from 9,500 gigawatt-hours to 45,000 gigawatt-hours. The scheme was scheduled to continue until 2030.[60] This target has since been revised with the Gillard government introducing in January 2011 an expanded target of 45,000 GWh of additional renewable energy between 2001 and 2020.[61]

The MRET was split in 2012 into a small scale renewable energy scheme (SRES) and large scale renewable energy target (LRET) components to ensure that adequate incentive exists for large scale grid connected renewable energy.[62] A number of states have also implemented their own renewable energy targets independent of the Commonwealth. For example, the Victorian Renewable Energy Target Scheme (VRET) mandated an additional 5% of Victoria's "load for renewable generation", although this has since been replaced by the new Australian Government LRET and SRES targets.[62] South Australia achieved its target of 20% of renewable supply by 2014 three years ahead of schedule (i.e. in 2011) and has subsequently established a new target of 33% to be achieved by 2020.[63]

Renewable Energy Certificates Registry

The Renewable Energy Certificates Registry (REC-registry) is an internet based registry system that is required by the Australian Renewable Energy (Electricity) Act 2000.[64] The REC-registry is dedicated to: maintaining various registers (as set in the act); and facilitating the creation, registration, transfer and surrender of renewable energy certificates (RECs).

Carbon pricing

In 2012, the Gillard government implemented a carbon price of $23 per tonne to be paid by 300 liable entities representing the highest business emitters in Australia. The carbon price will increase to $25.40 per tonne by 2014–15, and then will be set by the market from 1 July 2015 onwards.[65] It is expected that in addition to encouraging efficient use of electricity, pricing carbon will encourage investment in cleaner renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power. Treasury modelling has projected that with a carbon price, energy from the renewables sector is likely to reach 40 per cent of supply by 2050.[66] Analysis of the first 6 months of operation of the carbon tax have shown that there has been a drop in carbon emissions by the electricity sector. It has been observed that there has been a change in the mix of energy over this period, with less electricity being sourced from coal and more being produced by renewables such as hydro and wind power.[67] The government at the time presented this analysis as an indicator that their policies to promote cleaner energy are working.[67] The carbon pricing legislation was repealed by the Tony Abbott-led Australian Government on 17 July 2014.[68] Since then, carbon emissions from the electricity sector have increased.[69]

Clean Energy Finance Corporation

The Australian Government has announced the creation of the new 10 billion dollar Clean Energy Finance Corporation which will commence business in July 2013. The goal of this intervention is to overcome barriers to the mobilisation of capital by the renewable energy sector. It will make available two billion dollars a year for five years for the financing of renewable energy, energy efficiency and low emissions technologies projects in the latter stages of development. The government has indicated that the fund is expected to be financially self-sufficient producing a positive return on investment comparable to the long term bond rate.[15][70]

Feed-in tariffs

Feed-in tariffs have been enacted on a state by state basis in Australia to encourage investment in renewable energy by providing above commercial rates for electricity generated from sources such as rooftop photovoltaic panels or wind turbines.[3] The schemes in place focus on residential scale infrastructure by having limits that effectively exclude larger scale developments such as wind farms. Feed-in tariffs schemes in Australia started at a premium, but have mechanisms by which the price paid for electricity decreases over time to be equivalent or below the commercial rate.[3] All the schemes now in place in Australia are "net" schemes whereby the householder is only paid for surplus electricity over and above what is actually used. In the past, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory enacted "gross" schemes whereby householders were entitled to be paid for 100% of renewable electricity generated on the premises, however these programs have now expired. In 2008 the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to harmonise the various state schemes and developed a set of national principles to apply to new schemes.[71] Leader of the Australian Greens, Christine Milne, has advocated a uniform national "gross" feed-in tariff scheme, however this proposal has not been enacted.[72] Currently each state and territory of Australia offers a different policy with regards to feed in tariffs[73]

Subsidies to fossil fuel industry

There is dispute about the level of subsidies paid to the fossil fuel industry in Australia. The Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) argues that according to the definitions of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), fossil fuel production and use is subsidised in Australia by means of direct payments, favourable tax treatment, and other actions. It is suggested these measures act as impediments to investment in renewable energy resources.[74] Analysis by the ACF indicates that these provisions add up to a total annual subsidy of A$7.7 billion, with the most significant component being the Fuel Tax Credits program that rebates diesel fuel excise to many business users.[75] This analysis is disputed by the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) who argue that the ACF's definition of a subsidy differs from that of the OECD and that the fuel tax rebate schemes are in place to ensure that all producers are treated equally from a tax point of view. However, the IPA acknowledges that regardless of perceived issues with the ACF analysis, some level of fossil fuel subsidy is likely in existence.[76]

Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol

Australia ratified the Kyoto Protocol in December 2007 under the then newly elected Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. Evidence suggests Australia will meet its targets required under this protocol. Australia had not ratified the Kyoto Protocol until then, due to concerns over a loss of competitiveness with the US, which also rejects the treaty.[77]

Policy uncertainty

The Australian government has no renewable energy policy beyond the year 2020, raising concerns about environmental sustainability for future generations.[78] The Liberal party's energy minister, Angus Taylor, has also stated that the government will not be replacing the 'Renewable Energy Target' (RET) after 2020.[78]

However, there are a range of state government based policies which are due to compensate for the lack of policies from the Australian federal government as stated below:

The Victorian Government has set a Victorian Renewable Energy Target (VRET) of 50% by 2030.[79] Victoria also has a long-term target of net zero emissions by 2050.[79]

The Queensland Government has a commitment to a 50% renewable energy target by 2030.[80]

The New South Wales Government aims to have zero emissions across the New South Wales economy by 2050.[81]

In 2016, the ACT Government legislated a target of sourcing 100% renewable electricity by 2020.[82]

The Tasmanian Government is on track to achieve its target of 100% renewable energy by 2022.[83]

The South Australian Government has a 75% renewable energy target by 2025.[84] The Liberal government says it expects the state will be "net" 100 per cent renewables by 2030.[85]

The Northern Territory Government has committed to a target of 50% renewable energy by 2030.[86] The Northern Territory Government is also set to have 10% renewable energy by 2020.[87]

Western Australia is the only state or territory yet to commit to a renewable energy target.[88] However, 21 Western Australian councils have called on the state's Labor government to adopt targets for a 50% renewable electricity supply by 2030, and net-zero emissions by 2050.[89]

Academic literature

Australia has a very high potential for renewable energy.[90] Therefore, the transition to a renewable energy system is gaining momentum in the peer-reviewed scientific literature.[91] Among them several studies have examined the feasibility of a transition to a 100% renewable electricity systems, which was found both practicable as well as economically and environmentally beneficial to combat global warming.[92][93][94]

Major renewable energy companies operating in Australia

BP Solar

BP has been involved in solar power since 1973 and its subsidiary, BP Solar, is now one of the world's largest solar power companies with production facilities in the United States, Spain, India and Australia.[95] BP Solar is involved in the commercialisation of a long life deep cycle lead acid battery, jointly developed by the CSIRO and Battery Energy, which is ideally suited to the storage of electricity for renewable remote area power systems (RAPS).[96]

Edwards

Edwards first began manufacturing water heaters in Australia in 1963. Edwards is now an international organisation which is a leader in producing hot water systems for both domestic and commercial purposes using solar technology. Edwards exports to Asia, the Pacific, the Americas, Europe, Africa and the Middle East.[97]

Eurosolar

Eurosolar was first formed in 1993, with an aim of providing photovoltaic systems to the masses. It focuses on solar power in multiple Australian capitals. They continue to install panels all around Australia.

Hydro Tasmania

Hydro Tasmania was set up by the State Government in 1914 (originally named the Hydro-Electric Department, changed to the Hydro-Electric Commission in 1929, and Hydro Tasmania in 1998). Today Hydro Tasmania is Australia's largest generator of renewable energy. They operate thirty hydro-electric stations and one gas power station, and are a joint owner in three wind farms.

Meridian Energy Australia

Meridian Energy Australia runs a number of renewable energy assets (4 wind farms and 4 hydro plants) and only produces renewable energy – it claims to be Australasia's largest 100% renewable energy generator.

Nectr

Nectr is an Australian-based electricity retailer that focuses on offering renewable energy plans and services. Launched in 2019,[98] it currently operates in New South Wales, South East Queensland and South Australia, planning to expand to Victoria, Tasmania and the ACT in 2022. Nectr is owned by Hanwha Energy, an affiliate of South Korea's Hanwha Group, one of the global leaders in renewable energy technology, including solar power (Hanwha Q Cells) and battery storage technologies. The company offers 100% carbon offset plans, GreenPower plans and also launched solar and battery installation bundles in Ausgrid and Endeavour within NSW.[99] Its parent company Hanwha Energy Australia is an investor in Australian utility-scale solar power assets,[100] including the 20 MWAC Barcaldine solar farm in Queensland and the 88 MWAC Bannerton solar farm in Victoria. It is currently developing two new solar farms in southern NSW with capacity to produce enough energy to supply 50,000 homes.[101]

Origin Energy

Origin Energy is active in the renewable energy arena, and has spent a number of years developing several wind farms in South Australia, a solar cell business using technology invented by a team led by Professor Andrew Blakers at the Australian National University,[102] and geothermal power via a minority shareholding stake in Geodynamics.[103]

Pacific Blue

Pacific Blue is an Australian company that specialises in 100% renewable energy generation. Its focus is on hydroelectricity and wind power. Power stations owned by Pacific Blue include wind farms: Codrington Wind Farm, Challicum Hills Wind Farm, Portland Wind Project and Hydro power: Eildon Pondage Power Station, Ord River Hydro Power Station and The Drop Hydro.

Snowy Hydro Limited

Snowy Hydro Limited, previously known as the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority, manages the Snowy Mountains Scheme which generates on average around 4500 gigawatt hours of renewable energy each year, which represented around 37% of all renewable energy in the National Electricity Market in 2010. The scheme also diverts water for irrigation from the Snowy River Catchment west to the Murray and Murrumbidgee River systems.

Solahart

Solahart manufactured its first solar water heater in 1953, and products currently manufactured by Solahart include thermosiphon and split system solar and heat pump water heaters. These are marketed in 90 countries around the world and overseas sales represent 40% of total business. Solahart has a market share of 50% in Australia.[104]

Solar Systems

Solar Systems was a leader in high concentration solar photovoltaic applications,[105][106] and the company built a photovoltaic Mildura Solar concentrator power station, Australia.[107][108] This project will use innovative concentrator dish technology to power 45,000 homes, providing 270,000 MWh/year for A$420 million.[109] Solar Systems has already completed construction of three concentrator dish power stations in the Northern Territory, at Hermannsburg, Yuendumu, and Lajamanu, which together generate 1,555 MWh/year (260 homes, going by the energy/home ratio above). This represents a saving of 420,000 litres of diesel fuel and 1550 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions per year. The total cost of the solar power station was "A$7M, offset by a grant from the Australian and Northern Territory Governments under their Renewable Remote Power Generation Program".[110] The price of diesel in remote areas is high due to added transportation costs: in 2017, retail diesel prices in remote areas of the Northern Territory averaged $1.90 per litre. The 420,000 litres of diesel per year saved by these power stations in the first decade of operation would thus have cost approximately $8,000,000.

Wind Prospect

Wind Prospect developed the 46 MW Canunda Wind Farm in South Australia, which was commissioned in March 2005. A second South Australian wind farm, Mount Millar Wind Farm, was commissioned in January 2006 and this provides a further 70 MW of generation. More recently, a third wind farm has reached financial close for Wind Prospect in South Australia. This is the 95 MW Hallett Wind Farm which is expected to be fully commissioned late in 2008.

See also

- Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets

- Climate change in Australia

- Solar power in Australia

- Wind power in Australia

- Geothermal power in Australia

- Biofuel in Australia

- Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz

- Garnaut Climate Change Review

- Green electricity in Australia

- Greenhouse Mafia

- Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy

- List of countries by electricity production from renewable sources

- Greenhouse gas emissions by Australia

- Photovoltaic engineering in Australia

- Natural Edge Project

- Renewable Energy Certificates

- Renewable energy commercialisation

- Renewable energy by country

- Renewable energy in South Australia

- Energy in South Australia

- Centre for Appropriate Technology (Australia)

References

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2023" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- "Australian Energy Update 2018" (PDF). Department of Energy and Environment.

- Tim Flannery; Veena Sahajwalla (November 2012). "Critical Decade: Generating a Renewable Australia". Canberra: Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- Poddar, S., Evans, J.P., Kay, M. et al. Assessing Australia’s future solar power ramps with climate projections. Sci Rep 13, 11503 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38566-z

- Poddar, S., Evans, J. P., Kay, M., Prasad, A., Bremner, S.Estimation of future changes in photovoltaic potential in Australia due to climate change. Environmental Research Letters 2023. 16 (11): 114034

- "Australian Energy Statistics 2022 Energy Update Report" (PDF).

- CSIRO (2007). Rural Australia Providing Climate Solutions p.1

- Australian Conservation Foundation (2007). A Bright Future: 25% Renewable Energy for Australia by 2020

- Teske, Sven; Vincent, Julien. "Energy [r]evolution: A Sustainable Energy Australia Outlook" (PDF). Greenpeace International 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2008.

- Spratt, David and Sutton, Phillip, Climate Code Red: The case for a sustainability emergency, Friends of the Earth, Melbourne 2008

- "Renewable Energy Target: Legislation to cut RET passes Federal Parliament". ABC. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Australian Government: Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator – LRET-SRES Basics

- "Research: Stationary Energy Plan | Industry". www.bze.org.au. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- "How to be fully renewable in 10 years". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 August 2010.

- "Taxpayers to back $10bn renewable energy fund". The Australian. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- Michael Safi; Shalailah Medhora (22 December 2014). "Tony Abbott says repealing carbon tax his biggest achievement as minister for women". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "Clean Energy Australia Report 2012" (PDF). Southbank Victoria: Clean Energy Council. March 2013. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- "Tony Abbott has escalated his war on wind power, causing a cabinet split and putting international investment at risk". 11 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "2017: Biggest year for Australia's Renewable Energy Industry"

- "Renewable energy generates enough power to run 70% of Australian homes". The Guardian. 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "Australia has met its renewable energy target. But don't pop the champagne". RenewEconomy. 8 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- de Atholia, Timoth; Flannigan, Gordon; Lai, Sharon (19 March 2020). "Renewable Energy Investment in Australia". Reserve Bank of Australia.

- Mercer, Daniel (11 July 2022). "Australia 'on track' to generate half its electricity from renewable sources by 2025, report finds". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Snowy Hydro: Power Stations. Retrieved 19 November 2010 Archived 21 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "About". Snowy Hydro. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "Hydro: Energy". Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2018" (PDF). Clean Energy Council.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2021" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2020" (PDF). Clean Energy Council.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2013" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2014" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2015" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2016" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2019" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Clean Energy Council. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2022" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- "Australian PV market since April 2001". apvi.org.au.

- Lovegrove, Keith and Dennis, Mike. Solar thermal energy systems in Australia International Journal of Environmental Studies, Vol. 63, No. 6, December 2006, p. 791.

- Lovegrove, Keith and Dennis, Mike. Solar thermal energy systems in Australia International Journal of Environmental Studies, Vol. 63, No. 6, December 2006, p. 793.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (3 December 2014). "Environmental Issues: Energy Use and Conservation, Mar 2014". Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- PJT Solar Hot Water Archived 20 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Clean Energy Australia 2010 (Report)" (PDF). Official site. Clean Energy Council. pp. 5, 42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- CSIRO Solar Blog. Retrieved Nov 2011, http://csirosolarblog.com

- 'CSIRO Gets Sun Smart at the National Solar Energy Centre', June 2008, http://www.csiro.au/places/SolarEnergyCentre.html Archived 4 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Lovegrove, Keith and Dennis, Mike. Solar thermal energy systems in Australia International Journal of Environmental Studies, Vol. 63, No. 6, December 2006, p. 797.

- Solar Oasis: About

- ABC Rural (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- Big energy role for central Australia's hot rocks Mineweb, 2 May 2007.

- Scientists get hot rocks off over green nuclear power The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 2007.

- Energy superpower or sustainable energy leader? (PDF) Ecos, October–November 2007.

- "FACTBOX-Main renewables being developed in Australia". Reuters. 4 February 2009.

- Renewable Energy Commercialisation in Australia – Biomass Projects Archived 22 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Department of Industry and Science (2015), Australian Energy Statistics, Table C.

- Summary of report – Biomass energy production in Australia Status, costs and opportunities for major technologies Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Queensland Government. Ethanol case studies Archived 20 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- The biofuels promise: updated thinking Ecos, October–November 2006.

- "Car dependence in Australian cities: a discussion of causes, environmental impact and possible solutions" (PDF). Flinders University study. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "Australia's weaker emissions standards allow car makers to dump polluting cars". The Conversation. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "About ARENA". Australian Renewable Energy Agency. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- "Coalition attempts to rewrite history on support for wind, solar and RET". 15 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Australian Government: Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator Archived 26 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Parkinson, Giles (4 April 2011). "RET: Hail fellow, not well met". Climate Spectator. Business Spectator. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "Benefit of the Renewable Energy Target to Australia's Energy Markets and Economy. Report to the Clean Energy Council" (PDF). Clean Energy Council. August 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "A Renewable Energy Plan for South Australia" (PDF). RenewablesSA. Government of South Australia. 19 October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- "REC Registry". Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- "Clean Energy Regulator – Liable Entities Public Information Database".

- "Clean Energy Australia – Investing in the clean energy sources of the future" (PDF). Clean Energy Future. Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Uren, David (23 January 2013). "Emissions drop signals fall in carbon tax take". The Australian. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Vorrath, Sophie (17 July 2014). "Australia dumps carbon price, as repeal passes Senate".

- Yeates, Clancy (13 April 2015). "Coal makes a comeback thanks to carbon price repeal, emissions rise". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Clean Energy Finance Corporation Expert Review". Clean Energy Future. Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- "Feed-in tariffs". Parliament of Australia. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "NSW slashes its solar feed-in tariffs". The Fifth Estate. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Solar feed-in tariffs VIC WA NSW SA TAS QLD NT ACT". Solar Choice.

- "Fossil fuel subsidies". Australian Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- O'Conner, Simon (25 June 2010). "G20 and fossil fuel subsidies" (PDF). Australian Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Berg, Chris (2 February 2011). "The Truth About Energy Subsidies". Institute of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- Australian Government (2004). Securing Australia's Energy Future Archived 30 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Renewable energy investment to slump beyond 2020 amid policy uncertainty". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Department of Environment, Land; Energy (27 August 2019). "Victoria's renewable energy targets". Energy. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Queensland Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, Powering Queensland Plan: an integrated energy strategy for the state, Queensland Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, retrieved 1 September 2019

- Edis, Tristan (2 July 2019). "While the government is in denial, the states are making staggering progress on renewable energy | Tristan Edis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Directorate, ACT Government; PositionTitle=Manager; SectionName=Coordination and Revenue; Corporate=Environment and Planning (19 August 2019). "Renewable energy target legislation and reporting". Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate – Environment. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Tasmania to achieve 100 per cent renewables by 2022". Energy Magazine. 3 July 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Harmsen, political reporter Nick (21 February 2018). "SA to be powered by 75pc renewables by 2025 under new target". ABC News. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Parkinson, Giles (16 June 2019). "South Australia's stunning aim to be "net" 100 per cent renewables by 2030". RenewEconomy. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Morton, Adam (19 June 2019). "Clean energy found to be a 'pathway to prosperity' for Northern Territory". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Vorrath, Sophie (17 January 2019). "NT on track for 10% renewables by 2020, with two new solar farms announced". RenewEconomy. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Shepherd, Briana (16 October 2018). "WA 'right at the back of the pack' in renewable energy race". ABC News. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Vorrath, Sophie (31 May 2019). "W.A. councils demand "true to science" 50% renewable state target". RenewEconomy. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Shafiullah et al., Prospects of renewable energy e a feasibility study in the Australian context. In: Renewable Energy 39, (2012), 183–197, doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.08.016.

- Byrnes, L.; Brown, C.; Foster, J.; Wagner, L. (December 2013). "Australian renewable energy policy: Barriers and challenges". Renewable Energy. 60: 711–721. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2013.06.024.

- Elliston et al, Simulations of scenarios with 100% renewable electricity in the Australian National Electricity Market. In: Energy Policy 45, (2012), 606–613, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.03.011.

- Elliston et al, Least cost 100% renewable electricity scenarios in the Australian National Electricity Market. In: Energy Policy 59, (2013), 270–282, doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.038.

- Elliston et al. Comparing least cost scenarios for 100% renewable electricity with low emission fossil fuel scenarios in the Australian National Electricity Market. In: Renewable Energy 66, (2014), 196–204, doi:10.1016/j.renene.2013.12.010.

- Solar Power Profitability: BP Solar Environmental News Network, 25 May 2005.

- Wind energy round the clock

- Edwards solar hot water

- "Kudos, PV solutions for the masses and IP wars: the importance of being Q Cells". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "About us". Nectr. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "Nectr switched on for 100 days". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "Nectr executive scores CEC Women in Renewables AICD scholarship". pv magazine Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Origin Energy. SLIVER technology facts sheet

- Geodynamics: Power from the earth

- Solahart Industries Archived 30 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Solar Systems.Solar Systems wins National Engineering Excellence award Archived 21 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Solar technologies reaching new levels of efficiencies in Central Australia ABC Radio Australia, 12 November 2006.

- Solar Systems to Build A$420 million, 154MW Solar Power Plant in Australia

- Solar Systems. Solar Systems home page Archived 21 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Large Scale Solar Power" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- Archived 3 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Australian Conservation Foundation (2007). A Bright Future: 25% Renewable Energy for Australia by 2020 27 pages.

- Australian Government (2007). Australian Government Renewable Energy Policies and Programs 2 pages.

- CSIRO (2007). Climate Change in Australia: Technical Report 148 pages.

- CSIRO (2007). Rural Australia Providing Climate Solutions 54 pages.

- Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Paths to a Low Carbon Future 33 pages.

- ICLEI Oceania (2007). Biodiesel in Australia: Benefits, Issues and Opportunities for Local Government Uptake 95 pages.

- New South Wales Government (2006). NSW Renewable Energy Target: Explanatory Paper 17 pages.

- Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator (2006). Mandatory Renewable Energy Target Overview 5 pages.

- Renewable Energy Generators Australia (2006). Renewable Energy – A Contribution to Australia's Environmental and Economic Sustainability 116 pages.

- The Natural Edge Project, Griffith University, ANU, CSIRO and NFEE (2008). Energy Transformed: Sustainable Energy Solutions for Climate Change Mitigation 600+ pages.

- Greenpeace Australia Pacific Energy [R]evolution Scenario: Australia, 2008 ) 47 pages.

- Beyond Zero Emissions Zero Carbon Australia 2020, 2010 )

- Ison, Nicky (2018). A plan to repower Australia (PDF). Repower Australia 2018.

External links

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)

- Office of the Renewable Energy Regulator

- The Australian Centre for Renewable Energy (ACRE)

- "Climate change", Australian Government – Department of the Environment

- Map of operating renewable energy generators in Australia

- Renewable energy farms and Energy Georeference World map

- Desert Knowledge Australia Solar Centre

- Renew Economy

- Articles

- Australia no shining star of renewable energy

- MRET policy 'stills wind farm plans'

- Green energy market unviable: Vestas

- Cool wind blows for investors

- Riches in energy harvesting, farmers told

- Renewable energy revolution for NSW cane growers

- Australian breakthrough snapped up – by eager Americans

- Renewable Energy projects in Australia – By State

- Renewable Energy projects in Australia – By Type

- At its current rate, Australia is on track for 50% renewable electricity in 2025