Fertility tourism

Fertility tourism (also referred to as reproductive tourism or cross border reproductive care)[1][2][3] is the practice of traveling to another country or jurisdiction for fertility treatment,[4] and may be regarded as a form of medical tourism.[5] A person who can become pregnant is considered to have fertility issues if they are unable to have a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected intercourse.[6] Infertility, or the inability to get pregnant, affects about 8-12% of couples looking to conceive or 186 million people globally.[7] In some places, rates of infertility surpass the global average and can go up to 30% depending on the country. Areas with lack of resources, such as assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), tend to correlate with the highest rates of infertility.[8]

The main procedures sought are in vitro fertilization (IVF), artificial insemination by a donor, as well as surrogacy. These methods are types of assisted reproductive technology (ARTs).[9] Each of these three methods have varying popularity in different countries, with one method being more sought after in these destinations compared to another method in another country.

People are mainly driven towards fertility tourism due to lack of resources and high costs, while other contributing factors include cultural, religious, legal, and safety and efficacy issues.[10] Other impacts on the need for fertility treatments from other countries include those who are infertile, single, of older age, or identify as a part of the LGBTQIA+ community.[3] With these rising conditions, people end up having to travel to other countries in order to get the fertility treatments not accessible to them in their home countries.[6]

IVF

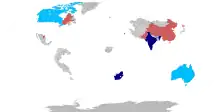

Destinations

About 20,000 to 25,000 women (often accompanied by their partners) annually seek cross-border assisted reproductive technology (ART) services.[11] Some countries are more popular than others as IVF destinations due to higher success rates and fewer regulations.[3] Even small countries such as Barbados provide JCI-accredited IVF treatment aimed at women from abroad.

Israel

Reproduction is a central goal in Israel, a leading fertility tourism destination for in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment with over three decades of major technologies in the assisted reproduction industry.[12] The trajectory of assisted reproductive technology is outlined through the expansion of IVF, the globalization of donating gametes, and the privatization of service.[13]

United States

Many Europeans travel to the United States because of the higher success rates and more liberal regulations under the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act, which was passed in 1992.[14] In the United States, affiliation between the right and left sides of the political spectrum motivated the protection of human life, even during the in vitro embryonic stages.[15]

India

India and other Asian countries are the main destinations for U.S. women seeking fertility treatment, being the destinations for 40% of U.S. women seeking IVF and 52% seeking IVF with egg donation.[16] The success rate of embryonic transfer through IVF has continually increased, resulting in more pregnancy outcomes.[17]

Mexico

In recent years, Mexico has become a destination for cross-border IVF treatment due to its liberal ART and egg donation policies with over 50 clinics throughout the country that utilize assisted reproductive technology.[18] Mexico does not have legal regulations that restrict or prohibit IVF or egg donations in Mexican clinics, making it a top destination for infertility treatment for people in the United States.[19]

Iran

The "Iranian ART revolution" is the term coined for the movement that has allowed the advancement of infertility treatment in Iran with over 70 operating IVF clinics, making it the one of the countries with the highest amount of clinics in the Middle East.[20][21] This may be due to various cultural or religious regulations against fertility treatments. In 2011, the mean cost of IVF ranged from $2250 to $3600 in government and private centers.[22]

Cost factors

Women from countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom may travel for IVF treatment and medications to save money. The cost of one IVF cycle in the United States averages US $15,000, while for comparable treatment in Mexico it is about US $7,800, Thailand $6,500, India $3,300, and Iran $2,500.[23][24] When calculating these costs, the costs of the hotel, travel, and hospital stay may also be considered in addition to the medical treatment.[25]

Egg donation

Egg donation is illegal in a number of European countries including Germany, Austria, and Italy. Many women then will seek treatment in places where the procedure is allowed, such as Spain and the United States where donors can be paid for their donation.[11] Almost half of all IVF treatments with donor eggs in Europe are performed in Spain.[11] IVF with anonymous egg donation is also the main ART sought by Canadians traveling to the U.S, and is the sought procedure for 80% of cross-border treatments by Canadians.[16]

Sex selection

Sex selection is prohibited in many countries, including the United Kingdom,[26] Australia[27] and Canada,[28] India,[29] except when it is used to screen for genetic diseases. Some women wishing to be sure of a child's sex may travel to countries where it is legal to perform a preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD, a potential expansion of IVF), which can be used for sex selection, such as in Iran and the United States.[30]

Multiple births

The rate of complications increases as more and more embryos are implanted.[31] Many countries have no restriction on how many embryos may be transferred into the uterus at the same time, increasing the risk of multiple pregnancy and resultant potential complications.[32] These complications may affect both the mother and the child. Birth defects have been thought to arise from IVF, however not enough information is available on this topic.[33] In 2005, 35% of all IVF–ET births in the US were multiple births (twins, triplets, or more).[34] The burden of multiple births generated by placing too many embryos is carried by the individuals and the home country.[35]

Donor insemination

Two thousand babies are born from treatments using sperm donations every year.[36] A woman may go to another country to obtain artificial insemination by donor. The motivation to seek donors from outside countries may come from a want for a greater variety of gamete donors. Stricter laws or an inability to meet the criteria necessary in ones respective countries are other possible reasons.[37] The practice is influenced by the attitudes and sperm donation laws in the host country.

There is generally a demand for sperm donors who have no genetic problems in their family, 20/20 eyesight, with excellent visual acuity, a college degree, and sometimes a value on a certain height, age, eye colour, hair texture, blood type and ethnicity .[38][39][40] According to sociology professor Lisa Jean Moore, there is "anecdotal evidence" that sperm from blonde, blue-eyed men is most in demand.[41]

Denmark

Denmark has a well-developed system of sperm export. This success mainly comes from the reputation of Danish sperm donors for being of high quality[42] and, in contrast with the law in the other Nordic countries, gives donors the choice of being either anonymous or non-anonymous to the receiving couple.[42] The maximum amount of families that may use the sperm of one donor is capped at 12.[43] Nordic sperm donors tend to be tall, with rarer features like blond hair or different color eyes and a light complexion, and highly educated and have altruistic motives for their donations,[44] partly due to the relatively low monetary compensation in Nordic countries. More than 50 countries worldwide are importers of Danish sperm, including Paraguay, Canada, Kenya, and Hong Kong.[42]

United States

US sperm is equally sought out for. Denmark and the United States both claim that they have the largest sperm bank supply. Specifically, the California Cryobank believes it is the largest sperm bank in the world. The donations from this sperm bank has reached over 100 countries and accounts for over 75,000 births globally. There is no limit as to how many families may use the donation of one sperm donor.[43]

Shortages

Some countries such as United Kingdom and Sweden, have a shortage of sperm donors.[45][46] Sweden now has an 18-month-long waiting list for donor sperm.[47]

As a consequence of the shortage of donor sperm in UK in the late 1990s and the early years of the 21st century, British women travelled to Belgium and Spain for donor insemination,[48] until those two countries changed their laws and imposed a maximum number of children one donor may produce. Prior to the change in the law, the limit in the number of children born to each donor depended upon practitioners at fertility clinics, and Belgian and Spanish clinics were purchasing donor sperm from abroad to satisfy demand for treatments. Anonymous donation was permitted in Belgium and is a legal requirement in Spain. These two countries also allowed single heterosexual and single and coupled lesbians to undergo fertility treatment. Ironically, at the time, many Belgian and Spanish clinics were buying sperm from British clinics donated by British donors, and they were able to use that sperm according to local laws and limits. In addition, lesbian women from France and eastern Europe travelled to these countries in order to achieve a pregnancy by an anonymous donor since this treatment was not available to them in their own countries. British fertility tourists must therefore now travel to other countries particularly those that do not include children born to foreigners in their national totals of children produced by each donor. Britain also imports donor sperm from Scandinavia but can only limit the use of that donor's sperm to ten families in the UK itself, so that more children may be produced elsewhere from the same donor.[49]

At least 250[47] Swedish sperm recipients travel to Denmark annually for insemination. Some of this is also due to that Denmark also allows single women to be inseminated.

It is illegal to pay donors for eggs or sperm in Canada. Women can still import commercial U.S. sperm, but that is not true for eggs, resulting in many Canadian women leaving the country for such procedures.[50]

Surrogacy

Legal controversies and citizenship

There are differing amounts of laws and regulations on surrogacy around the world regarding the legality of surrogacy, who can be a surrogate or receive this service, if fertility tourism is legal, and if surrogates can be compensated for their services; dictate where potential parents travel to obtain surrogacy.[51] For instance, there are places where there is a lack of laws or guidelines for surrogacy and many custody battles have resulted in outlawing surrogacy and deeming parental rights to the surrogate over the intended parents, or fully legalizing surrogacy all together.[52] In countries where surrogacy is banned, there have been many instances where the intended parents go to different destination for surrogacy, but then have difficulty bringing their new children back to their countries. Also, there are some countries that ban commercial surrogacy, but allow unpaid "altruistic surrogacy" and also provide contracts to the involved parties.[52]

The citizenship and legal status of a child resulting from surrogacy can be problematic. The Hague Conference Permanent Bureau identified the question of citizenship of these children as a "pressing problem" in the Permanent Bureau 2014 Study (Hague Conference Permanent Bureau, 2014a: 84-94).[53][54] According to the Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State, either one or both of the child's genetic parents must be a U.S. citizen for the child to be considered a U.S. citizen. In other words, the only way for the child to acquire U.S. citizenship automatically at birth is if he/she is biologically related to a U.S. citizen. Further, in some countries, the child will not be a citizen of the country in which he/she is born because the surrogate mother is not legally the parent of the child. This could result in a child being born without citizenship.[55]

Religious views

There are many differing religious views surrounding surrogacy with regards to lineage and heritability, motherhood, and marital fidelity. Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and other Christian denominations outside of Catholicism generally approve of surrogacy, but each with some concerns. With Judaism, there are concerns regarding legitimacy and most tend to believe that motherhood belongs to the person who actively delivers the child.[56] Hinduism views infertility as a curse to be cured by any means necessary, generally approving of surrogacy. There is Islamic religious concern centered mainly around the importance of and confusion of lineage and inheritance. Other Christian denominations have a wide variety of views from encouraging surrogacy as it shares the blessing of parenthood, to viewing surrogacy as a means of confused identity in a child and a disruption in traditional marital practices and procreation. Catholicism; however, generally views any third party involved in marriage or procreation to be an intrusion, and thus commonly views gestational surrogacy as an intrusion to the marital bond.[51] Religion has led to legal bans on surrogacy in some countries. For instance, in Costa Rica the Catholic church successfully lobbied to ban surrogacy.[57]

Destinations

Some countries, such as the United States, Canada, Georgia, Ukraine, and Russia are popular foreign surrogacy destinations.[58] Eligibility, processes and costs differ from country to country. Previously popular destinations, India, Nepal, Thailand, and Mexico have since 2014 banned commercial surrogacy for non-residents or allow it only for heterosexual married couples.[59] Thailand criminalized surrogacy by foreigners and same-sex couples in 2014, prompted by incidents of surrogate parents behaving badly. The most notable of those cases was that of Baby Gammy, a twin born with Down syndrome and left behind by the Australians who contracted his birth (his sister, who was not born with the disorder, was taken with them to Australia). It did not help that Gammy's biological father was also a convicted sex offender.

Fertility tourism for surrogacy is driven by legal restrictions in the home country or the incentive of lower prices abroad. Popular destinations are those which permit commercial gestational surrogacy, where the cost is relatively low, and which give the intended parents legal rights over the newborn child, whether by streamlined adoption procedures or direct parental rights.

India

India was a main destination for surrogacy because of the relatively low cost until international surrogacy was outlawed in 2015.[60] Although there are no official figures available, a 2012 United Nations report counted around 3,000 fertility clinics in India.[61] India's surrogacy business was estimated at around $1 billion annually.[61]

Indian surrogates became increasingly popular amongst intended parents in industrialized nations because of the relatively low costs and easy access offered by Indian surrogacy agencies.[62] Clinics charged people between $10,000 and $28,000 for the complete package, including fertilization, the surrogate's fee, and delivery of the baby at a hospital.[63] Including the costs of flight tickets, medical procedures and hotels, this represented roughly a third of the price of the procedure in the UK and a fifth of that in the US.[64]

In 2013, surrogacy by foreign homosexual couples and single parents was banned.[65] In 2015, the government banned commercial surrogacy in India and permitted entry of embryos only for research purposes.[66]

Russia

Liberal legislation makes Russia attractive for “reproductive tourists” looking for techniques not available in their countries. Intended parents come there for oocyte donation, because of advanced age or marital status (single women and single men) and when surrogacy is considered. Gestational surrogacy, even commercial is absolutely legal in Russia, being available for practically all adults willing to be parents.[67] Foreigners have the same rights for assisted reproduction as Russian citizens. Within 3 days after the birth the commissioning parents obtain a Russian birth certificate with both their names on it. Genetic relation to the child (in case of donation) doesn’t matter.[68] On 4 August 2010, a Moscow court ruled that a single man who applied for gestational surrogacy (using donor eggs) could be registered as the only parent of his son, becoming the first man in Russia to defend his right to become a father through a court procedure.[69] The surrogate mother’s name was not listed on the birth certificate; the father was listed as the only parent. However, courts do not always take the side of such parents. In 2014, a Moscow court denied registration of the baby born via surrogacy to the single man; the decision was upheld on appeal.[70]

Ukraine

Ukraine has seen a significant increase in international surrogacy since 2015, when the practice was banned in several Asian countries that had been popular destinations.[71] Surrogacy is completely legal in Ukraine. However, only healthy mothers who have had at least one child before can become surrogates.[72] Ukrainian surrogate mother are mostly from small towns or rural areas.[72] The full surrogate package may cost around $50,000, with the surrogate receiving less than 50% of that amount.[72] Surrogates in Ukraine have zero parental rights over the child,[72] as stated on Article 123 of the Family Code of Ukraine. Thus, a surrogate cannot refuse to hand the baby over in case she changes her mind after birth.[71] Only married couples can legally go through gestational surrogacy in Ukraine, but they have to be able to prove they cannot carry a baby themselves for medical reasons.[71] Also at least one parent must have a genetic link to the baby (egg donors are therefore frequently used).[71] Gay couples and single parents are prohibited to use gestational surrogates.[71]

Belarus

Surrogacy is legally allowed in Belarus from 2006, however, major clients for such kind of services in this country are mainly Russian citizens.[73] According to Belarusian legislation, surrogacy can be used here due to strict medical indications by married heterosexual couples and single women (for single women only in case they are able to provide their own oocytes).[74] Unlike Russia or Ukraine, in Belarus Intended Mother is written not only in the legal birth certificate issued by local authorities, but also appear in the medical birth certificate given by the Maternity House, where delivery of the surrogate mother took place. This gives to the Intended Parents legal ability to take baby directly from the Maternity house, being sure that no one will claim parental rights over the children born via surrogacy.[75]

In Belarus only healthy women in the age from 20 to 35 years old, who are in legal marriage and have at least one healthy child can be surrogate mothers. Essential conditions of surrogacy agreement, that should be notarized, are also specified in the Law "On Assisted Reproductive Technologies".[76]

United States

People travel to the United States for surrogacy procedures for the high quality of medical technology and care, as well as the high level of legal protections afforded through some US state courts to surrogacy contracts as compared to other countries. Increasingly, same sex couples who face restrictions using IVF and surrogacy procedures in their home countries travel to US states where it is legal.

The United States is occasionally sought as a location for surrogate mothers by couples seeking a green card in the US, since the resulting child can get birthright citizenship in the United States and can thereby apply for green cards for the parents when the child turns 21 years of age.[77] Surrogacy costs in USA between $95,000 and $150,000 for the complete package, including fertilization, legal fees, compensation, the agency's fee.[78]

Canada

Canada has recently become a more popular foreign surrogacy destination, with almost half the babies born to Canadian surrogates in British Columbia in 2016 and 2017 being for foreign parents.[79]

Numerous reasons have been proposed to explain Canada's rising popularity as an international surrogacy destination. For one, Canada is one of the few destinations that still allows surrogacy for foreign commissioning parents.[79] While, Greece, Ukraine, Russia, Georgia and a few U.S. states also permit surrogacy for foreign commissioning parents, Canada does not discriminate on the basis of marital status or sexual orientation.[79] Canada is also attractive because it is fairly efficient in granting legal parental rights, declaring legal parenthood and issuing birth certificates within weeks of birth.[79] This contrasts with other countries with lengthier processes that often deter commissioning parents wanting to quickly return home with their new babies.[79] Canada's strong and universal healthcare system also makes it a favourable international surrogacy destination, as pregnant women in Canada receive high-quality, publicly funded healthcare throughout pregnancy, during delivery, and after birth.[79] This reduces the risk of pregnancy complications, which is often a significant concern of commissioning parents.

References

- Bergmann, Sven (2011). "Fertility tourism: circumventive routes that enable access to reproductive technologies and substances". Signs. 36 (2): 280–288. doi:10.1086/655978. ISSN 0097-9740. PMID 21114072. S2CID 22730138.

- Matorras R (December 2005). "Reproductive exile versus reproductive tourism". Human Reproduction. 20 (12): 3571, author reply 3571–2. doi:10.1093/humrep/dei223. PMID 16308333.

- Salama M, Isachenko V, Isachenko E, Rahimi G, Mallmann P, Westphal LM, et al. (July 2018). "Cross border reproductive care (CBRC): a growing global phenomenon with multidimensional implications (a systematic and critical review)". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 35 (7): 1277–1288. doi:10.1007/s10815-018-1181-x. PMC 6063838. PMID 29808382.

- McFedries P (17 May 2006). "wordspy.com". wordspy.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Hanefeld J, Horsfall D, Lunt N, Smith R (2013). "Medical tourism: a cost or benefit to the NHS?". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e70406. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870406H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070406. PMC 3812100. PMID 24204556.

- Farquhar C, Marjoribanks J (August 2018). "Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane Reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD010537. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010537.pub5. PMC 6953328. PMID 30117155.

- Mascarenhas MN, Flaxman SR, Boerma T, Vanderpoel S, Stevens GA (2012). "National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveys". PLOS Medicine. 9 (12): e1001356. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001356. PMC 3525527. PMID 23271957.

- Inhorn MC, Patrizio P (1 July 2015). "Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (4): 411–26. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv016. PMID 25801630.

- Kushnir VA, Barad DH, Albertini DF, Darmon SK, Gleicher N (January 2017). "Systematic review of worldwide trends in assisted reproductive technology 2004-2013". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 15 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/s12958-016-0225-2. PMC 5223447. PMID 28069012.

- Inhorn MC, Patrizio P (1 July 2015). "Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (4): 411–26. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmv016. PMID 25801630.

- Kovacs P (14 June 2010). "Seeking IVF Abroad: Medical Tourism for Infertile Couples". Medscape. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "IMS Fertility Unit". Medicaltourismforyou.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Birenbaum-Carmeli D (June 2016). "Thirty-five years of assisted reproductive technologies in Israel". Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online. 2: 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.rbms.2016.05.004. PMC 5991881. PMID 29892712.

- "Policy Document | Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Jasanoff S, Metzler I (29 January 2018). "Borderlands of Life". Science, Technology, & Human Values: 016224391775399. doi:10.1177/0162243917753990. ISSN 0162-2439.

- Hughes EG, Dejean D (June 2010). "Cross-border fertility services in North America: a survey of Canadian and American providers". Fertility and Sterility. 94 (1): e16-9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.008. PMID 20149916.

- Malhotra N, Shah D, Pai R, Pai HD, Bankar M (October 2013). "Assisted reproductive technology in India: A 3 year retrospective data analysis". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 6 (4): 235–40. doi:10.4103/0974-1208.126286. PMC 3963305. PMID 24672161.

- González-Santos, Sandra P (June 2016). "From esterilología to reproductive biology: The story of the Mexican assisted reproduction business". Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online. 2: 116–127. doi:10.1016/j.rbms.2016.10.002. ISSN 2405-6618. PMC 5991872. PMID 29892724.

- "IVF treatment in Mexico - costs, reviews and clinics". EggDonationFriends.com. 4 September 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Abbasi-Shavazi MJ, Inhorn MC, Razeghi-Nasrabad HB, Toloo G (2008). "The "Iranian ART Revolution": Infertility, Assisted Reproductive Technology, and Third-Party Donation in the Islamic Republic of Iran". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies. 4 (2): 1–28. doi:10.2979/MEW.2008.4.2.1. ISSN 1552-5864. S2CID 53737215.

- Inhorn, Marcia C. (2012). The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies, and Islam in the Middle East. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14889-2. JSTOR j.ctt7st3b.

- Abedini, Mehrandokht; Ghaheri, Azadeh; Omani Samani, Reza (1 October 2016). "Assisted Reproductive Technology in Iran: The First National Report on Centers, 2011". International Journal of Fertility and Sterility. 10 (3): 283–289. doi:10.22074/ijfs.2016.5044. ISSN 2008-076X. PMC 5027601. PMID 27695610.

- Miller AM (15 December 2015). "Should You Travel Abroad for IVF?". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Woodman J (17 February 2015). Patients Beyond Borders: Everybody's Guide to Affordable, World-Class Medical Travel. Healthy Travel Media. ISBN 978-0990315407.

- Hanefeld J, Horsfall D, Lunt N, Smith R (24 October 2013). "Medical tourism: a cost or benefit to the NHS?". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e70406. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...870406H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070406. PMC 3812100. PMID 24204556.

- US clinic offers British couples the chance to choose the sex of their child From The Times. 22 August 2009

- "Designing your own child: Australia's regulations - BioNews". www.bionews.org.uk. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Krishan S. Nehra, Library of Congress. Sex Selection & Abortion: Canada

- "Sex Selection & Abortion: India | Law Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Nehra, Krishan. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - US clinic offers British couples the chance to choose the sex of their child From The Times. 22 August 2009

- "What is IVF? The process, risks, success rates and more". Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Health warning to women over fertility tourism Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Xpert Fertility Care of California

- "Our campaign to reduce multiple births | Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority". www.hfea.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Kathpalia SK, Kapoor K, Sharma A (July 2016). "Complications in pregnancies after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 72 (3): 211–4. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2015.11.010. PMC 4982974. PMID 27546958.

- Klitzman R (December 2016). "Deciding how many embryos to transfer: ongoing challenges and dilemmas". Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online. 3: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.rbms.2016.07.001. PMC 5846681. PMID 29541689.

- "Donors | Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority". www.hfea.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Deonandan, Raywat (17 August 2015). "Recent trends in reproductive tourism and international surrogacy: ethical considerations and challenges for policy". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 8: 111–119. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S63862. ISSN 1179-1594. PMC 4544809. PMID 26316832.

- The Genius Sperm Bank June 2006

- Baby steps; how lesbian alternative insemination is changing the world. By Amy Agigian

- Bowmaker SW (2005). economics uncut. Edward Elgar. ISBN 9781845425807. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Sperm counts: overcome by man's most precious fluid By Lisa Jean Moore, retrieved 22 January 2011

- Assisted Reproduction in the Nordic Countries Archived 11 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine ncbio.org

- Youn, Soo (15 August 2018). "America's hottest export? Sperm". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- FDA Rules Block Import of Prized Danish Sperm Posted 13 August, 08 7:37 AM CDT in World, Science & Health

- "HFEA Background Briefing on Sperm, Egg and Embryo Donation". Hfea.gov.uk. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- "HFEA Figures for New Donor Registrations". Hfea.gov.uk. 30 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Ekerhovd E, Faurskov A, Werner C (2008). "Swedish sperm donors are driven by altruism, but shortage of sperm donors leads to reproductive travelling". Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 113 (3): 305–13. doi:10.3109/2000-1967-241. PMID 18991243.

- Wordspy In turn citing Madeleine Bunting, "X+Y=$: the formula for genetic imperialism," The Guardian, 16 May 2006

- [Shortage of Sperm Donors in Britain Prompts Calls for Change] By DENISE GRADY. Published: 11 November 2008 The New York Times

- My scattered grandchildren The Globe and Mail. Alison Motluk. Sunday, 13 September 2009 07:53PM EDT

- Deonandan R (February 2020). "Thoughts on the ethics of gestational surrogacy: perspectives from religions, Western liberalism, and comparisons with adoption". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 37 (2): 269–279. doi:10.1007/s10815-019-01647-y. PMC 7056787. PMID 31897847.

- Roth AE, Wang SW (July 2020). "Popular repugnance contrasts with legal bans on controversial markets". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (33): 19792–19798. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11719792R. doi:10.1073/pnas.2005828117. PMC 7443974. PMID 32727903.

- "HCCH - New site". hcch.net.

- Darnovsky, Marcy; Beeson, Diane (31 December 2014). "RePub, Erasmus University Repository: Global surrogacy practices". ISS Working Paper Series / General Series. repub.eur.nl. 601: 1–54.

- "Important Information for U.S. Citizens Considering the Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Abroad". travel.state.gov. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- "Jewish Law - Articles ("The Establishment of Maternity & Paternity in Jewish and American Law")". www.jlaw.com. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Inhorn MC, Patrizio P (June 2012). "The global landscape of cross-border reproductive care: twenty key findings for the new millennium". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 24 (3): 158–63. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e328352140a. PMID 22366965. S2CID 25865884.

- Deonandan R (2015). "Recent trends in reproductive tourism and international surrogacy: ethical considerations and challenges for policy". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 8: 111–9. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S63862. PMC 4544809. PMID 26316832.

- Preiss D, Shahi P (31 May 2016). "The Dwindling Options for Surrogacy Abroad". The Atlantic. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Sachdev C (4 July 2018). "Once the go-to place for surrogacy, India tightens control over its baby industry". Public Radio International. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "India Plans Surrogacy Ban for Foreigners, Same-Sex Couples". NBC News. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Shetty P (10 November 2018). "India's unregulated surrogacy industry" (PDF). World Report. 380: 1663–1664.

- "16 Things You Should Know About IVF Treatment". Fight Your Infertility. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Kannan S (18 March 2009). "Regulators Eye India's Surrogacy Sector". India Business Report, BBC World. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- "India bans gay foreign couples from surrogacy". Daily Telegraph. 18 January 2013. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Timms O (5 March 2018). Ghoshal R (ed.). "Ending commercial surrogacy in India: significance of the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2016". Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 3 (2): 99–102. doi:10.20529/IJME.2018.019. PMID 29550749.

- "jurconsult.ru" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Svitnev K (June 2010). "P-307 In limbo: legalization of children born abroad through surrogacy". Human Reproduction: i235–i236. doi:10.1093/humrep/de.25.s1.306.

- "Surrogacy in Russia and Abroad". surrogacy.ru. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Judges did not agree on how to register children born from a surrogate mother". garant.ru. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Ponniah K (13 February 2018). "In search of surrogates, foreign couples descend on Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Bezpiatchuk Z (19 May 2020). "Coronavirus splits couple from baby born through surrogacy 8,000 miles away". BBC. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Gryb S (21 May 2017). "Surrogacy in Belarus. Reasons, nuances, taboos" (in Russian). Minsk-news. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017.

- Antonenko Y (27 December 2017). "Surrogacy under the legislation of the Republic of Belarus" (in Russian). Grodno Regional Attorney Association. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019.

- Sidarok I (12 July 2018). "Everything you need to know about surrogacy" (in Russian). Zviazda news. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019.

- "Law On Assisted Reproductive Technologies No.341-3 dated 7 January 2012" (in Russian). Kodeksy-by. 7 January 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018.

- Harney, Alexandra (23 September 2013). "Wealthy Chinese Seek U.S. Surrogates for Second Child, Green Card". Reuters Health Information (via Medscape).

- Houghton B. "How much does surrogacy cost? A lot less than you think". Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "How Canada became an international surrogacy destination". Retrieved 27 March 2019.