Research history of Mosasaurus

This research history of Mosasaurus documents the historical, cultural, and scientific accounts surrounding the Mosasaurus, a genus of extinct aquatic squamate reptile that lived during the Late Cretaceous.

First discoveries

First skull TM 7424

The first remains of Mosasaurus known to science are fragments of a skull discovered in 1764 at a subterranean chalk quarry under Mount Saint Peter, a hill near Maastricht, the Netherlands. It was collected by Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Drouin in 1766 and was procured in 1784 by museum director Martinus van Marum for the Teylers Museum at Haarlem. In 1790, Van Marum published a description of the fossil, considering it to be a species of "big breathing fish" (in other words, a whale) under the classification Pisces cetacei.[1] This skull is still in the museum's collections and is cataloged as TM 7424.[2]

Second skull and historical capture

Around 1780,[lower-alpha 1] a second more complete skull was discovered at the same quarry. A retired Dutch army physician named Johann Leonard Hoffmann took a keen interest in this specimen, who corresponded with the famous biologist Petrus Camper regarding its identification. Hoffmann, who had previously collected various mosasaur bones in 1770, presumed that the animal was a crocodile.[3] Camper disagreed, and in 1786 he concluded that the remains were of an "unknown species of toothed whale". He published his studies of the fossil that year in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London,[5] the most prestigious scientific journal in the world at the time, giving the second skull international fame.[6] During this time, the fossil was under the possession of canon Theodorus Joannes Godding, who owned the portion of the land it was discovered in. Godding was struck by its beauty and took every measure to conserve it, eventually displaying it inside a grotto behind his house.[3]

Maastricht, an important Dutch fortress city at the time, was captured during the French Revolutionary Wars by the armies of General Jean-Baptiste Kléber in November 1794. Four days after the conquest, the fossil was looted from Godding's possession by French soldiers due to its international scientific value[6] under Kléber's orders,[7] carried out by political commissar Augustin-Lucie de Frécine. According to an account by Godding's niece and heiress Rosa, Frécine first pretended to be interested in studying the famous remains and corresponded with Godding via letter to arrange a visit to his cottage to personally examine it. Frécine never visited, and instead sent six armed soldiers to forcefully confiscate the fossil under the pretext that he was ill and wanted to study it at his home.[3][6] Four days after the seizure, the National Convention decreed that the specimen was to be transported to the National Museum of Natural History, France (MNHN). By the time it arrived at the museum, various parts of the skull were lost. In an 1816 reclamation request, Rosa claimed that she still possessed two missing parts that were not taken by Frécine. However, the fate of these bones is unknown, and some historians believe that Rosa mentioned them in hopes of negotiating indemnity. The French government refused to return the fossil but recompensed Godding in 1827 by exempting him from war taxes.[6]

Cultural legend concerning second skull

There is a popular legend regarding Godding's ownership of the second skull and its subsequent acquisition by the French, which is based on the account of geologist Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond (one of four men that arrived in Maastricht in January 1795 to confiscate any public objects of scientific value for France) in his 1798 publication Histoire naturelle de la montagne de Saint-Pierre de Maestricht (Natural history of the mountain of Saint-Pierre of Maastricht). According to Faujas, Hoffmann was the original owner of the specimen, which he purchased from the quarrymen and helped excavate. When the news of this discovery reached Godding, whom Faujas painted as a malevolent figure, he sought to take possession of the greatly valuable specimen for himself and filed a lawsuit against Hoffmann, claiming his rights as landowner. Due to Godding's position as a canon, he influenced the courts and was able to force Hoffmann to relinquish the fossil and pay the costs of the lawsuit. When Maastricht was attacked by the French, the artillerymen were aware that the famous fossil was stored at Godding's house. Godding did not know his house was spared and he hid the specimen in a secret location in town. After the city's capture, Faujas personally helped secure the fossil while Frécine offered a reward of 600 bottles of good wine to anyone who would locate and bring to him the skull undamaged. The next day, twelve grenadiers brought the fossil safely to Frécine after assuring full compensation to Godding and collected their promised reward.[3][6]

Historians have found little evidence to back up Faujas' account. For example, there is no evidence that Hoffmann ever possessed the fossil, that a lawsuit involved him and Godding, or that Faujas was directly involved in acquiring the fossil. More reliable but contradictory accounts suggest that his narrative was mostly made up: Faujas was known to be a notorious liar who commonly embellished his stories, and it is likely that he falsified the story to disguise evidence of looting from a private owner (which was a war crime), to make French propaganda, or to simply impress others. Nevertheless, the legend created by Faujas' embellishment helped elevate the second skull into cultural fame.[3][6]

Fate of TM 7424

Unlike its renowned contemporary, the first skull TM 7424 was not seized by the French after the capture of Maastricht. During Faujas and his colleagues' mission in 1795, the collections of Teylers Museum, although famous, were protected from confiscation. The four men may have been instructed to protect all private collections unless its owner was declared a rebel. However, this protection may have also been due to van Marum's acquaintance with Faujas and André Thouin (another of the four men) since their first meeting in Paris in July 1795.[3]

Identification and naming

Early hypotheses as a crocodile or cetacean

Before the second skull was seized by the French in late 1794, the two most popular hypotheses regarding its identification were that it represented the remains of either a crocodile or whale, as first argued by Hoffmann and Camper respectively. Hoffmann's identification as a crocodile was viewed by many at the time to be the most obvious answer; there were no widespread ideas of evolution and extinction at the time, and the skull superficially resembled a crocodile.[8] Moreover, among the various mosasaur bones Hoffmann collected in 1770 were phalanx bones which he assembled and placed onto a gypsum matrix; historians have noted that Hoffmann placed the reconstruction into the matrix in a way that distorted the view of some of the phalanges, creating an illusion that claws are present, which Hoffmann likely took as further evidence of a crocodile.[9] Camper based his argument for a whale identity on four points. First, Camper noted that the skull's jawbones had a smooth texture and its teeth were solid at the root, similar to those in sperm whales and dissimilar to the crocodile's porous jawbones and hollow teeth. Second, Camper obtained mosasaur phalanges which he noted to be significantly different from those of crocodiles and instead suggested paddle-shaped limbs, which were another cetacean feature. Third, Camper noted the presence of teeth in the pterygoid bone of the skull, which he observed are not present in crocodiles but are present in many species of fish (Camper also thought that the rudimentary teeth of the sperm whale, which he erroneously believed was a species of fish, corresponded to pterygoid teeth). Lastly, Camper pointed out that all other fossils from Maastricht are marine, which indicates that the animal represented by the skull must have been a marine animal. Because he erroneously believed that crocodiles are entirely freshwater animals, Camper concluded by process of elimination that the animal could only be a whale.[8]

Identification as an extinct marine lizard

The second skull arrived at the MNHN in 1795, where it is now cataloged as MNHN AC 9648. It attracted the attention of more scientists and was referred to as le grand animal fossile des carrières de Maestricht,[3] or the "great animal of Maastricht".[lower-alpha 2][2] One of the scientists was Camper's son Adriaan Gilles Camper. Originally intending to defend his father's arguments, Camper Jr. instead became the first to understand that the crocodile and cetacean hypotheses were both erroneous; based on his own examinations of MNHN AC 9648 and his father's fossils, he found that their anatomical features were more similar to squamates and varanoids. He concluded that the animal must have been a large marine lizard with varanoid affinities. In 1799, Camper Jr. discussed his conclusions with the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. Cuvier studied MNHN AC 9648, and in 1808 he confirmed Camper Jr.'s identification of a large marine lizard, but as an extinct form unlike any today.[8] The fossil had already become part of Cuvier's first speculations on the possibility of species going extinct, which paved the way for his theory of catastrophism or "consecutive creations", one of the predecessors of the theory of evolution. Prior to this, almost all fossils, when recognized as having come from once-living life forms, were interpreted as forms similar to those of the modern day. Cuvier's idea of the Maastricht specimen being a gigantic version of a modern animal unlike any species alive today seemed strange, even to him.[10] The idea was so important to Cuvier that in 1812 he proclaimed:

Above all, the precise determination of the famous animal from Maastricht seems to us as important for the theory of zoological laws, as for the history of the globe.

Cuvier justified his concepts by trusting his techniques in the then-developing field of comparative anatomy, which he had already used to identify giant extinct members of other modern groups.[10]

Even though the binomial naming system was well established at the time, Cuvier never designated a scientific name to the new species and for a while, it continued being referred to as the "great animal of Maastricht". In 1822, English doctor James Parkinson published a conversation that included a suggestion made by Llandaff dean William Daniel Conybeare to refer to the species as the Mosasaurus as a temporary name until Cuvier decided on a permanent scientific name. Cuvier never made one; instead, he himself adopted Mosasaurus as the species' genus and designated MNHN AC 9648 as its holotype. In 1829, English paleontologist Gideon Mantell added the specific epithet hoffmannii in 1829 in honor of Hoffmann.[lower-alpha 3][2][12]

During his 1799 correspondence with Cuvier, Camper Jr. reported the existence of a second species of Mosasaurus based on comparisons between the holotype and some of his father's fossils, a finding he would later publish in 1812 without erecting a scientific name.[8][13] However, Cuvier rejected the idea that the known Mosasaurus fossils at the time may represent two species. The purported species that Camper Jr. detected was M. lemonnieri, which was formally described nearly a century later by Louis Dollo in 1889.[8]

Early American discoveries

Earliest discoveries

The first possible recorded discovery of a mosasaur in North America was of a partial skeleton described as "a fish" in 1804 by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark's Corps of Discovery during their 1804–1806 expedition across the western United States. It was found by Sergeant Patrick Gass on black sulfur bluffs near the Cedar Island alongside the Missouri River[14][15] and consisted of some teeth and a disarticulated vertebral column measuring 45 feet (14 m) in length. Four members of the expedition recorded the discovery in their journals including Clark and Gass.[15] Some parts of the fossil were collected and sent back to Washington, D.C., where it was lost before any proper documentation could be made. In 2003, Richard Ellis speculated that the remains may have belonged to M. missouriensis;[16] however competing speculations include that of a tylosaurine mosasaur or a plesiosaur.[17]

The earliest description of North American fossils firmly attributed to the genus Mosasaurus was made in 1818 by naturalist Samuel L. Mitchill. The described fossils were of a tooth and jaw fragment recovered from a marl pit from Monmouth County, New Jersey, which Mitchell described as "a lizard monster or saurian animal resembling the famous fossil reptile of Maestricht", implying that the fossils had affinities with the then-unnamed M. hoffmannii holotype from Maastricht. Cuvier was aware of this discovery but doubted whether it belonged to the genus Mosasaurus. An unnamed foreign naturalist "unreservedly" declared that the fossils instead belonged to a species of Ichthyosaurus. In 1830, zoologist James Ellsworth De Kay reexamined the specimen; he concluded that it was indeed a species of Mosasaurus and was considerably larger than the M. hoffmannii holotype, making it the largest fossil reptile ever discovered on the continent at the time.[18] Whether the two belonged to the same species or not remained unknown until 1838 when German paleontologist Heinrich Georg Bronn designated the New Jersey specimen as a new species and named it Mosasaurus dekayi in honor of De Kay's efforts.[19] However, the specimen was lost and the taxon was declared a nomen dubium in 2005.[12][20] There are some additional fossils from New Jersey that have been historically referred to as M. dekayi, but paleontologists have reidentified them as fossils of M. hoffmannii.[12][21]

M. missouriensis saga

The type specimen of the second described species M. missouriensis (RFWUIP 1327) was first discovered in the early 1830s, recovered by a fur trapper near the Big Bend of the Missouri River. This specimen, which consisted of some vertebrae and a partially complete articulated skull notably missing the end of its snout, was brought back to St. Louis, where it was purchased by an Indian agent as home decoration. This fossil caught the attention of German prince Maximilian of Weid-Neuwied during his 1832–1834 travels in the American West. He purchased the fossil and delivered it to University of Bonn naturalist Georg August Goldfuss for research. Goldfuss carefully prepared and described the specimen, which he concluded in 1845 was of a new species of Mosasaurus and in 1845 named it M. maximiliani in honor of Maximilian.[14]

However, earlier in 1834, American naturalist Richard Harlan published a description of a partial fossil snout he obtained from a trader from the Rocky Mountains who found it in the same locality as the Goldfuss specimen. Harlan thought it belonged to a species of Ichthyosaurus based on perceived similarities with the skeletons from England in features of the teeth and positioning of the nostrils and named it Ichthyosaurus missouriensis.[22] In 1839, he revised this identification after noticing differences in the premaxillary bone and pores between the snouts of the fossil and those of Ichthyosaurus and instead thought that the fossil actually pertained to a new genus of a frog or salamander-like amphibian, reassigning it to the genus Bactrachiosaurus.[23] For unknown reasons, a publication in the same year from the Société géologique de France documented Harlan reporting the new genus as Bactrachotherium.[24] In 1845, Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer argued that the snout belonged to neither an ichthyosaur nor an amphibian but to a mosasaur, and suspected that it may have been the snout that was missing in the Goldfuss skull. This could not be confirmed at the time because the fossil snout became lost. In 2004, it was rediscovered inside the collections of the MNHN under the catalog number MNHN 958; records revealed that Harlan at one point donated the fossil to the museum, where it was promptly forgotten. The snout matched perfectly into the Goldfuss skull, confirming that it was the specimen's missing snout. Because of its earlier description, Harlan's taxon took priority, making the final scientific name M. missouriensis.[14]

Later discoveries

Confirmed species other than M. hoffmannii and M. missouriensis (considered to be the most well-known and studied species of the Mosasaurus genus) have been described.[25]

M. conodon

In 1881, Cope described the third Mosasaurus species from fossils including a partial lower jaw, some teeth and vertebrae, and limb bones sent to him from a colleague who discovered them in deposits around Freehold Township, New Jersey (AMNH 1380[26]).[27] Cope declared that the fossils represented a new species of Clidastes based on their slender build and named it Clidastes conodon.[27] But in 1966, paleontologists Donald Baird and Gerard R. Case reexamined the holotype fossils and found that the species belonged under Mosasaurus instead and renamed it Mosasaurus conodon.[26] Cope did not provide an etymology for the specific epithet conodon,[27] but etymologist Ben Creisler suggested that it may be a portmanteau meaning "cone tooth", derived from the Ancient Greek κῶνος (kônos, meaning "cone") and ὀδών (odṓn, meaning "tooth"), likely in reference to the smooth-surfaced conical teeth characteristic of the species.[28]

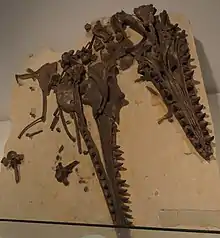

M. lemonnieri

_(20248316020).jpg.webp)

M. lemonnieri's reintroduction to science[8] and formal description in 1889 by Dollo was based on a fairly-complete skull (IRSNB R28[29]) recovered from a phosphate quarry owned by the Solvay S.A. company in the Ciply Basin of Belgium. The skull was one of many fossils donated to the Museum of Natural Sciences (IRSNB) by Alfred Lemonnier, the director of the quarry; as such, Dollo named the species in his honor.[30] In subsequent years, further mining of the quarry yielded additional well-preserved fossils of the species, some of which were described by Dollo in later papers. These fossils include multiple partial skeletons, nearly enough to represent M. lemonnieri's entire skeleton.[12][29] Despite being the most anatomically well-represented among the genus, the species was largely ignored by scientific literature. Paleontologist Theagarten Lingham-Soliar suggested two reasons for such neglect. The first reason was that M. lemonnieri fossils were endemic to Belgium and the Netherlands; these areas, despite the famous discovery of the M. hoffmannii holotype, have generally not attracted the attention of mosasaur paleontologists. The second reason was that M. lemonnieri was overshadowed by its more famous and history-rich congeneric M. hoffmannii.[29]

M. lemonnieri was historically a controversial taxon, and some have argued that it is synonymous with other species.[31] In 1967, Dale Russell argued that differences between the fossils of M. lemonnieri and M. conodon were too minor to support species-level separation; per the principle of priority, Russell designated M. lemonnieri as a junior synonym of M. conodon.[32] In a study published in 2000, Lingham-Soliar refuted Russell's classification through a comprehensive examination of IRSNB's specimens, identifying significant differences in skull morphology. However, he declared that better studies of M. conodon would be needed to settle the issue of synonymy.[29] Such a study was done in a 2014 paper by Ikejiri and Lucas, who both examined the skull of M. conodon in detail and also argued that M. conodon and M. lemonnieri are distinct species.[26] Alternatively, paleontologists Eric Mulder, Dirk Cornelissen, and Louis Verding suggested in a 2004 discussion that M. lemonnieri could actually be juvenile representatives of M. hoffmannii. This was justified by the argument that differences between the two species can only be observable in "ideal cases", and that these differences could be explained by age-based variation. However, there are still some differences such as the exclusive presence of fluting in M. lemonnieri teeth that might indicate the two species being distinct.[33] It has been expressed that better studies are still needed for more conclusive evidence of synonymy.[33]

M. beaugei

The fifth species, M. beaugei, was described in 1952 by French paleontologist Camille Arambourg in part of a large-scale project since 1934 to study and provide paleontological and stratigraphic data of Morocco to phosphate miners such as the OCP Group.[34] The species was described from nine isolated teeth originating from phosphate deposits in the Oulad Abdoun Basin and the Ganntour Basin in Morocco[35] and was named in honor of OCP General Director Alfred Beaugé, who invited Arambourg to partake in the research project and helped provide local fossils.[34][36] One of the teeth, MNHN PMC 7, was designated as the holotype. A 2004 study by Bardet et al. reexamined Arambourg's teeth and found that only three can be firmly attributed to M. beaugei. Two of the other teeth were described as having variations that may possibly be within the species but were ultimately not referred to M. beaugei, while the remaining four teeth were found to be unrelated to it and of uncertain identity. The study also described more complete M. beaugei fossils in the form of two well-preserved skulls recovered from the Oulad Abdoun Basin.[35]

Early depictions and developments

Scientists have initially imagined that Mosasaurus had webbed feet and terrestrial limbs and thus was an amphibious marine reptile capable of both terrestrial and aquatic locomotion. Scholars like Goldfuss argued that the skeletal features of Mosasaurus known at the time such as an elastic vertebral column indicated a walking ability; if Mosasaurus was entirely aquatic, it would have been better supported by a stiff backbone. But in 1854, German zoologist Hermann Schlegel became the first to prove through anatomical evidence that Mosasaurus had flippers instead of feet. Using fossils of Mosasaurus phalanges including the gypsum-encased specimens collected by Hoffmann (which Schlegel extracted from the gypsum, noting that it may have misled previous scientists), he observed that they were broad and flat and showed no indication of muscle or tendon attachment, indicating that Mosasaurus was incapable of walking and instead had flipper-like limbs for a fully aquatic lifestyle. Schlegel's hypothesis was largely ignored by his contemporaries, but was more widely accepted in the 1870s when more complete mosasaur fossils in North America were discovered by American paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.[8]

Crystal Palace statue

One of the earliest paleoart depictions of Mosasaurus is a life-size concrete sculpture constructed by natural history sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins between 1852 and 1854 as part of the collection of sculptures of prehistoric animals on display at the Crystal Palace Park in London. Hawkins sculpted the model under the direction of the English paleontologist Sir Richard Owen, who was informed on the possible appearance of Mosasaurus primarily based on the holotype skull. Given the knowledge of the possible relationships between Mosasaurus and monitor lizards, Hawkins depicted the prehistoric animal as essentially a water-going monitor lizard. The head was large and boxy, based on Owen's estimations of the holotype skull's dimensions being 2.5 feet (0.76 m) × 5 feet (1.5 m), with nostrils at the side of the skull, large volumes of soft tissue around the eyes, and lips reminiscent of monitor lizards. The skin was given a robust scaley texture similar to those found in larger monitor lizards such as the Komodo dragon. Depicted limbs include a right single flipper, which reflected on the aquatic nature of Mosasaurus.[37]

The model was uniquely sculpted deliberately incomplete, with only the head, back, and single flipper having been constructed. This is commonly attributed to Owen's lack of clear knowledge regarding the postcranial (behind the skull) anatomy of Mosasaurus, but Mark P. Witton found this unlikely given that Owen was able to guide a full speculative reconstruction of a Dicynodon sculpture, which was also known solely from skulls at the time. Witton instead suggested that time and financial constraints may have influenced Hawkins to cut corners and sculpt the Mosasaurus model in a way that would be incomplete but visually acceptable.[37] To hide the missing anatomical parts, the sculpture was partially submerged in the lake and placed near the Pterodactylus models at the far side of the main island.[38] Although some elements of the Mosasaurus sculpture such as the teeth have been accurately depicted, many elements of the model can be considered inaccurate, even at the time. The depiction of Mosasaurus with a boxy head, side-positioned nose, and flippers contradicted the studies of Goldfuss (1845), whose examinations of the vertebrae and skull of M. missouriensis instead called for a narrower skull, nostrils at the top of the skull, and amphibious terrestrial limbs (the latter of which is incorrect in modern standards). The ignorance of these findings may have been due to a general ignorance of Goldfuss's studies by other contemporaneous scientists.[37]

Notable specimens

CCMGE 10/2469

In 1927, political exile and socialist revolutionary M. A. Vedenyapin discovered the bones of a large marine reptile in the outskirts of Penza, in a ravine where Red Army soldiers were trained in machine gun shooting. After this find, the excavations then begin and the entire population of the city soon began to talk about the research in progress. In a church, a preacher gave a sermon that the bones came from an antediluvian animal that did not join Noah's ark, and many interested people often crowded around the excavations. Vedenyapin gave lectures on the geological past of Penza to tens of thousands of people who came to participate. During the discoveries, several cases of theft of fossils were reported, leading paleontologists to recruit a militiaman, then a Red Army patrol to secure the scene.[39]

The work was carried out quickly because of the rains which could potentially cause landslides on the slope. Bones of the lower jaw, scapula, vertebrae and ribs were found during the excavations. To ensure better preservation of the material found, the fossils were placed in boxes with the matrix and sent to the geological committee of Saint Petersburg. The bones were later attributed to the species M. giganteus.[lower-alpha 4] N. P. Stepanov is then responsible for mounting the skull, before it is exhibited at the Central Museum of Geological Exploration of Chernyshev, in Saint Petersburg. An exact copy in plaster was even sent to the regional museum in Penza. Unfortunately, the skull exhibited in Saint Petersburg will suffer the same fate as certain bones during the excavations: all the small unsecured bones and teeth were stolen by visitors to the museum. The skull was also covered with a glass jar very late.[39]

It was in 2014 that Dimitry V. Grigoriev analyzed in detail the identification and description of the specimen, which he attributed as coming from the type species of the genus, M. hoffmannii. With a length reaching 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in), the author considers that the owner of the lower jaw, cataloged CCMGE 10/2469, should reach 17.1 m (56 ft) in length, which would make it the largest known mosasaur taxon.[39] However, although CCMGE 10/2469 is one of the largest M. hoffmannii fossils ever discovered, later published studies suggest that the measurement model used by Grigoriev is likely exaggerated,[40] more recent estimates suggesting a reduced length of 13 m (43 ft) for the species.[41]

SDSM 452

In an unpublished 1953 thesis, Harlan Martin described in detail a particularly well-preserved skeleton of a Mosasaurus, now housed at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The author classified the specimen in a species proposed, but not recognized by the ICZN[lower-alpha 5], named M. 'poultneyi', which he considered to be close to the species M. missouriensis.[42] Since most of the skull of this specimen, cataloged as SDSM 452, was lost to erosion, direct comparisons with extant skulls of M. missouriensis are impractical. In 1967, Russell reidentified SDSM 452 as a representative of the species M. conodon, although he pointed out some resemblance to M. missouriensis.[32]

The proposal made by Russell would be immediately challenged by later published studies, especially on the basis of questionable anatomical features. In two studies published between 1993 and 1997 respectively, Gorden L. Bell Jr. did not consider SDSM 452 assignable to M. conodon,[43] a claim also shared in the rediagnosis of the species by Ikejiri and Lucas in 2014.[26] In her 2016 thesis, Street mentioned that it is possible that the specimen belongs to M. missouriensis based on observations made on the bones, but further studies are needed to confirm this claim.[12]

TMP 2008.036.0001

In 2008, several Canadian workers made an important discovery of a large marine reptile in South Alberta, within the Bearpaw Formation. The fossil concerned is immediately exhumed, and the specimen will subsequently be dated to around 75 million years old and cataloged TMP 2008.036.0001. The analysis and discovery of this specimen is formalized by Takuya Konishi and his colleagues in an article published in 2014 by the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. After identification, the authors assign the fossil as coming from a representative of one of the officially recognized species of the genus Mosasaurus, M. missouriensis. The specimen has a skull measuring 66 cm (26 in) for an estimated body length of 4.8 m (16 ft),[11] while the largest representatives have skulls measuring 1 m (3 ft 3 in) for a body length generally set at 6 m (20 ft),[12] suggesting it would have been a juvenile or subadult individual.[11] Although the fossil skeleton is incomplete, it is one of the best preserved mosasaur specimens identified to date: it contains the cartilaginous rings of the trachea and sternum and even the disarticulated remains of a large fish measuring 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long. The presence of this fish confirms in passing that the representatives of the species M. missouriensis consumed prey larger than their head, dismembering and consuming bits at the same time.[11]

The study by Konishi et al. (2014) also suggest that due to the presence of larger mosasaurs that specialized in hardy prey, notably Prognathodon, M. missouriensis likely specialized more on prey best consumed using cutting-adapted teeth in an example of niche partitioning.[11]

History of taxonomy

Early status as a wastebasket taxon

Because nomenclature rules were not well-defined at the time, 19th century scientists did not give Mosasaurus a proper diagnosis during its first descriptions. This led to ambiguity regarding the definition of the genus, which led it to become a wastebasket taxon that contained as many as fifty different species. The taxonomic issue was so severe that there were cases of species found to be junior synonyms of species found to be junior synonyms themselves. For example, four taxa became junior synonyms of M. maximus, which itself became a junior synonym of M. hoffmannii. This issue was recognized by many scientists at the time, but efforts to clean up the taxonomy of Mosasaurus were hindered due to a lack of a clear diagnosis.[25][12]

In 1967, Russell published Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs, which contained one of the earliest proper diagnoses of Mosasaurus. Although his work is considered incomplete as he worked solely on North American representatives and did not examine European representatives such as M. hoffmannii in-depth, Russell significantly revised the genus and established a diagnosis that was clearer than previous descriptions. He considered eight species as valid—M. hoffmannii, M. missouriensis, M. conodon, M. dekayi, M. maximus, M. gaudryi, M. lonzeensis, and M. ivoensis.[25][12] Scientists during the late 1990s and early 2000s would revise this further: M. maximus was synonymized with M. hoffmannii by Mulder (1999) although some scientists maintain that it is a distinct species,[25][12] M. lemonnieri was resurrected by Lingham-Soliar (2000), M. ivoensis and M. gaudryi were moved to the genus Tylosaurus by Lindgren and Siverson (2002) and Lindgren (2005) respectively,[25][12][44] and M. dekayi and M. lonzeensis became dubious.

During the late 20th century, scientists described four additional species from fossils in the Pacific—M. mokoroa, M. hobetsuensis, M. flemingi, and M. prismaticus.[25][12] In 1995, Lingham-Soliar published one of the earliest modern diagnoses of M. hoffmannii, which provided detailed descriptions of the type species' known anatomy based on a wealth of fossils from deposits around Maastricht.[45] However, some have criticized it for its reliance on referred specimens rather than primarily the holotype as it is normally the convention to establish a species diagnosis using the type specimens, especially on IRSNB R12, a fossil skull questionably attributed to the species.[25][12]

Taxonomic clarification

In 2016, the doctoral thesis of Hallie Street was published. This thesis, supervised by Michael Caldwell, performed the first proper description and diagnosis of M. hoffmannii based solely on its holotype since its identification over two hundred years prior.[12] This reassessment of the holotype specimen clarified the ambiguities that plagued earlier researchers and allowed for a significant taxonomic revision of Mosasaurus. A phylogenetic study was performed, testing the relationships between M. hoffmannii and twelve candidate Mosasaurus species—M. missouriensis, M. dekayi, M. gracilis, M. maximus, M. conodon, M. lemonnieri, M. beaugei, M. ivoensis, M. mokoroa, M. hobetsuensis, M. flemingi, and M. prismaticus. Of these twelve, only M. missouriensis and M. lemonnieri were found as distinct species within the genus. M. beaugei, M. dekayi, and M. maximus were recovered as junior synonyms of M. hoffmannii. The placement of M. gracilis and M. ivoensis outside of the Mosasaurinae subfamily was also reaffirmed. M. hobetsuensis and M. flemingi were recovered as representatives of Moanasaurus and renamed accordingly. M. mokoroa and M. prismaticus were recovered as distinct genera, named Antipodinectes and Umikosaurus respectively. Representatives of M. conodon from the Midwestern United States were found to belong to M. missouriensis, while its East Coast representatives became a new genus subsequently named Aktisaurus while preserving the specific epithet conodon. Lastly, the study found IRSNB R12 skull to be a distinct species of Mosasaurus. It was named 'M. glycys', the specific epithet being a romanization of the Ancient Greek γλυκύς (ɡlykýs, meaning "sweet") in reference to the skull's residence in Belgium and the country's "reputation for chocolate production". Street stated that contents of the thesis are intended to be published as scientific papers.[12]

The diagnosis of the Mosasaurus holotype was published in a 2017 peer-reviewed paper co-authored with Caldwell.[25] The taxonomic revision of the genus has yet to be formally published[lower-alpha 5] but has been verbally referenced in Street and Caldwell (2017)[25] and in abstracts presented at meetings[48][49] Street and Caldwell (2017) also presented a brief preliminary taxonomic review of Mosasaurus that identified five likely valid species—[lower-alpha 6] M. hoffmannii, M. missouriensis, M. conodon, M. lemonnieri, and M. beaugei—and considered the four Pacific species to be possibly valid, pending formal reassessment in the future. M. dekayi was included in the list without its dubious status addressed, although as a likely synonym of M. hoffmannii.[25] In addition, the assessment of M. beaugei as a valid species revised[25] Street (2016)'s prior synonymization based on additional anatomical distinctions.[12]

See also

Footnotes

- The exact year is not fully certain due to multiple contradicting claims. An examination of existing historical evidence by Pieters et al., (2012) suggested that the most accurate date would be on or around 1780.[3] More recently, Limburg newspapers reported in 2015 that Ernst Homburg discovered a Liège magazine issued in the October 1778 reporting in detail a recent discovery of the second skull.[4]

- A more literal translation would be "the great fossil animal of the quarries of Maastricht".

- hoffmannii was the original spelling used by Mantell, ending with -ii. Later authors began to drop the final letter and spelled it as hoffmanni, as became the trend for specific epithets of similar structure in later years. However, recent scientists argue that the special etymological makeup of hoffmannii cannot be subjected to International Code of Zoological Nomenclature Articles 32.5, 33.4, or 34, which would normally protect similar respellings. This makes hoffmannii the valid spelling, although hoffmanni continues to be incorrectly used by many authors.[11]

- This species is now considered as a junior synonym of M. hoffmannii.[25]

- As the revision remains restricted to a PhD thesis, it is defined as an unpublished work per Article 8 of the ICZN and therefore not formally valid.[46][47]

- As in independent of Street's thesis.[25]

References

- M. van Marum (1790). Beschrijving der beenderen van den kop van eenen visch, gevonden in den St Pietersberg bij Maastricht, en geplaatst in Teylers Museum (in Dutch). Vol. 9. Verhandelingen Teylers Tweede Genootschap. pp. 383–389.

- Mike Everhart (1999). "Mosasaurus hoffmanni-The First Discovery of a Mosasaur?". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Florence Pieters; Peggy G. W. Rompen; John W. M. Jagt; Nathalie Bardet (2012). "A new look at Faujas de Saint-Fond's fantastic story on the provenance and acquisition of the type specimen of Mosasaurus hoffmanni MANTELL, 1829". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 183 (1): 55–65. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.183.1.55.

- Vikkie Bartholomeus (September 21, 2015). "Datum vondst mosasaurus ontdekt: in oktober 1778". 1Limburg (in Dutch). Archived from the original on March 7, 2020.

- Petrus Camper (1786). "Conjectures relative to the petrifactions found in St. Peter's Mountain near Maestricht". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 76 (2): 443–456. doi:10.1098/rstl.1786.0026. ISSN 2053-9223.

- Florence F. J. M. Pieters (2009). "Natural history spoils in the Low Countries in 1794/95: the looting of the fossil Mosasaurus from Maastricht and the removal of the cabinet and menagerie of stadholder William V". Napoleon's legacy: the rise of national museums in Europe, 1794–1830 (PDF). Vol. 27. Berlin: G+H Verlag. pp. 55–72. ISBN 9783940939111.

- Nathalie Bardet (2012). "The Mosasaur collections of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle of Paris". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 183 (1): 35–53. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.183.1.35.

- Eric Mulder (2004). Maastricht Cretaceous finds and Dutch pioneers in vertebrate palaeontology. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. pp. 165–176.

- Eric Mulder; Bert Theunissen (1986). "Hermann Schlegel's investigation of the Maastricht mosasaurs". Archives of Natural History. 13 (1): 1–6. doi:10.3366/anh.1986.13.1.1.

- Mark Evans (2010). "The roles played by museums, collections and collectors in the early history of reptile palaeontology". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 5–29. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.343....5E. doi:10.1144/SP343.2. S2CID 84158087.

- Takuya Konishi; Michael Newbrey; Michael Caldwell (2014). "A small, exquisitely preserved specimen of Mosasaurus missouriensis (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Campanian of the Bearpaw Formation, western Canada, and the first stomach contents for the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 802–819. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34..802K. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.838573. S2CID 86325001.

- Hallie P. Street (2016). A re-assessment of the genus Mosasaurus (Squamata: Mosasauridae) (PDF) (PhD). University of Alberta. doi:10.7939/R31N7XZ1K.

- Adriaan Gilles Camper (1812). "Mémoire sur quelques parties moins connues du squelette des sauriens fossiles de Maestricht". Annales du Muséum d'histoire naturelle (in French). 19: 215–241.

- Mike Everhart (2001). "The Goldfuss Mosasaur". Oceans of Kansas. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- "September 10, 1804". Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- Richard Ellis (2003). Sea Dragons: Predators of the Prehistoric Oceans. University Press of Kansas. p. 216. ISBN 978-0700613946.

- Robert W. Meredith; James E. Martin; Paul N. Wegleitner (2007). The largest mosasaur (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Missouri River area (Late Cretaceous; Pierre Shale Group) of South Dakota and its relationship to Lewis and Clark (PDF). The Geological Society of America. pp. 209–214.

- James Ellsworth De Kay (1830). "On the Remains of Extinct Reptiles of the genera Mosasaurus and Geosaurus found in the secondary formation of New-Jersey; and on the occurrence of the substance recently named Coprolite by Dr. Buckland, in the same locality". Annals of the Lyceum of Natural History of New York. 3: 134–141.

- Heinrich Georg Bronn (1838). Lethaea geognostica oder Abbildungen und Beschreibungen der für die Gebirgs-Formationen bezeichnendsten Versteinerungen (in German). Vol. 2. Stuttgart. p. 760. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.59080.

- William B. Gallagher (2005). "Recent mosasaur discoveries from New Jersey and Delaware, USA: stratigraphy, taphonomy and implications for mosasaur extinction". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 84 (3): 241–245. doi:10.1017/S0016774600021028.

- Eric W. A. Mulder (1999). "Transatlantic latest Cretaceous mosasaurs (Reptilia, Lacertilia) from the Maastrichtian type area and New Jersey". Geologie en Mijnbouw. 78 (3/4): 281–300. doi:10.1023/a:1003838929257. S2CID 126956543.

- Richard Harlan (1834). "Notice of the Discovery of the Remains of the Ichthyosaurus in Missouri, N. A.". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 4: 405–408. doi:10.2307/1004839. JSTOR 1004839.

- Richard Harlan (1839). "Notice of the discovery of Basilosaurus and Batrachotherium". Proceedings of the Geological Society of London. 3: 23–24.

- Richard Harlan (1839). "(Letter regarding Basilosaurus and Batrachotherium)". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France (in French). 1 (10): 89–90.

- Hallie P. Street; Michael W. Caldwell (2017). "Rediagnosis and redescription of Mosasaurus hoffmannii (Squamata: Mosasauridae) and an assessment of species assigned to the genus Mosasaurus". Geological Magazine. 154 (3): 521–557. Bibcode:2017GeoM..154..521S. doi:10.1017/S0016756816000236. S2CID 88324947.

- T. Ikejiri; S. G. Lucas (2014). "Osteology and taxonomy of Mosasaurus conodon Cope 1881 from the Late Cretaceous of North America". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 94 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1017/njg.2014.28. S2CID 73707936.

- Edward Drinker Cope (1881). "A new species of Clidastes from New Jersey". American Naturalist. 15: 587–588.

- Ben Creisler (2000). "Mosasauridae Translation and Pronunciation Guide". Dinosauria On-line. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008.

- Theagarten Lingham-Soliar (2000). "The Mosasaur Mosasaurus lemonnieri (Lepidosauromorpha, Squamata) from the Upper Cretaceous of Belgium and The Netherlands". Paleontological Journal. 34 (suppl. 2): S225–S237.

- Louis Dollo (1889). "Première note sur les Mosasauriens de Mesvin". Bulletin de la Société belge de géologie, de paléontologie et d'hydrologie (in French). 3: 271–304. ISSN 0037-8909.

- Pablo Gonzalez Ruiz; Marta S. Fernandez; Marianella Talevi; Juan M. Leardi; Marcelo A. Reguero (2019). "A new Plotosaurini mosasaur skull from the upper Maastrichtian of Antarctica. Plotosaurini paleogeographic occurrences". Cretaceous Research. 103 (2019): 104166. Bibcode:2019CrRes.10304166G. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.06.012. hdl:11336/125124. S2CID 198418273.

- Dale A. Russell (1967). Systematics and morphology of American mosasaurs (PDF). Vol. 23. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. pp. 1–124.

- Daniel Madzia (2019). "Dental variability and distinguishability in Mosasaurus lemonnieri (Mosasauridae) from the Campanian and Maastrichtian of Belgium, and implications for taxonomic assessments of mosasaurid dentitions". Historical Biology. 32 (10): 1–15. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1588892. S2CID 108526638.

- Camille Arambourg (1952). Les vertébrés fossiles des gisements de phosphates (Maroc–Algérie–Tunisie) (PDF). Notes et Mémoires du Service Géologique (in French). Vol. 92. Paris: Typographie Firmin-Didot. pp. 1–372. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-11-27.

- Nathalie Bardet; Xabier Pereda Suberbiola; Mohamed Iarochene; Fatima Bouyahyaoui; Baadi Bouya; Mbarek Amaghzaz (2004). "Mosasaurus beaugei Arambourg, 1952 (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco". Geobios. 37 (2004): 315–324. Bibcode:2004Geobi..37..315B. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2003.02.006.

- Nathalie Bardet; Xabier Pereda Suberbiola; Stephane Jouve; Estelle Bourdon; Peggy Vincent; Alexandra Houssaye; Jean-Claude Rage; N.-E Jalil; B. Bouya; M. Amaghzaz (2010). "Reptilian assemblages from the latest Cretaceous – Palaeogene phosphates of Morocco: from Arambourg to present time". Historical Biology. 22 (1–3): 186–199. doi:10.1080/08912961003754945. S2CID 128481560.

- Mark Witton (2019). "The science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, part 2: Teleosaurus, pterosaurs and Mosasaurus". Mark Witton.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019.

- "Mosasaurus". Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs. 2020. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020.

- Dimitry V. Grigoriev (2014). "Giant Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Penza, Russia" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 318 (2): 148–167. doi:10.31610/trudyzin/2014.318.2.148. S2CID 53574339.

- Terri J. Cleary; Roger B. J. Benson; Susan E. Evans; Paul M. Barrett (2018). "Lepidosaurian diversity in the Mesozoic–Palaeogene: the potential roles of sampling biases and environmental drivers". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (3): 171830. Bibcode:2018RSOS....571830C. doi:10.1098/rsos.171830. PMC 5882712. PMID 29657788.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2022). The Princeton Field Guide to Mesozoic Sea Reptiles. Princeton University Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 9780691193809.

- Harlan Martin (1953). Mosasaurus poultneyi: A South Dakota Mosasaur (Thesis). South Dakota School of Mines and Technology.

- Gorden L. Bell Jr. (1997). "A Phylogenetic Revision of North American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea". Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press. pp. 293–332. doi:10.1016/b978-012155210-7/50017-x. ISBN 978-0-12-155210-7.

- Johan Lindgren (2005). "The first record of Hainosaurus (Reptilia: Mosasauridae) from Sweden" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 79 (6): 1157–1165. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1998.tb00520.x.

- Theagarten Lingham-Soliar (1995). "Anatomy and functional morphology of the largest marine reptile known, Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Mosasauridae, Reptilia) from the Upper Cretaceous, Upper Maastrichtian of The Netherlands". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 347 (1320): 155–172. Bibcode:1995RSPTB.347..155L. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0019. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019.

- International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. "Article 8. What constitutes published work".

- Mike Taylor (2010). "Notes on Early Mesozoic Theropods and the future of zoological nomenclature". Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021.

- Hallie P. Street; Michael W. Caldwell (2016), A reexamination of Mosasaurini based on a systematic and taxonomic revision of Mosasaurus (PDF). 5th Triannual Mosasaur Meeting- a global perspective on Mesozoic marine amonites. May 16–20. Abstract. p. 43-44.

- Hallie P. Street. "Reassessing Mosasaurini based on a systematic revision of Mosasaurus". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 4: 42. ISSN 2292-1389.