Retroactive data structure

In computer science a retroactive data structure is a data structure which supports efficient modifications to a sequence of operations that have been performed on the structure. These modifications can take the form of retroactive insertion, deletion or updating an operation that was performed at some time in the past.[1]

Some applications of retroactive data structures

In the real world there are many cases where one would like to modify a past operation from a sequence of operations. Listed below are some of the possible applications:

- Error correction: Incorrect input of data. The data should be corrected and all the secondary effects of the incorrect data be removed.

- Bad data: When dealing with large systems, particularly those involving a large amount of automated data transfer, it is not uncommon. For example, suppose one of the sensors for a weather network malfunctions and starts to report garbage data or incorrect data. The ideal solution would be to remove all the data that the sensor produced since it malfunctioned along with all the effects the bad data had on the overall system.

- Recovery: Suppose that a hardware sensor was damaged but is now repaired and data is able to be read from the sensor. We would like to be able to insert the data back into the system as if the sensor was never damaged in the first place.

- Manipulation of the past: Changing the past can be helpful in the cases of damage control and retroactive data structures are designed for intentional manipulation of the past.

Time as a spatial dimension

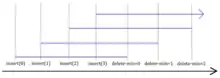

It is not possible to consider time as an additional spatial dimension. To illustrate this suppose we map the dimension of time onto an axis of space. The data structure we will use to add the spatial time dimension is a min-heap. Let the y axis represent the key values of the items within the heap and the x axis is the spatial time dimension. After several insertions and delete-min operations (all done non-retroactively) our min-heap would appear like in figure 1. Now suppose we retroactively insert zero to the beginning of the operation list. Our min-heap would appear like in figure 2. Notice how the single operation produces a cascading effect which affects the entire data structure. Thus we can see that while time can be drawn as a spatial dimension, operations with time involved produces dependence which have a ripple when modifications are made with respect to time.

Comparison to persistence

At first glance the notion of a retroactive data structures seems very similar to persistent data structures since they both take into account the dimension of time. The key difference between persistent data structures and retroactive data structures is how they handle the element of time. A persistent data structure maintains several versions of a data structure and operations can be performed on one version to produce another version of the data structure. Since each operation produces a new version, each version thus becomes an archive that cannot be changed (only new versions can be spawned from it). Since each version does not change, the dependence between each version also does not change. In retroactive data structures we allow changes to be made directly to previous versions. Since each version is now interdependent, a single change can cause a ripple of changes of all later versions. Figures 1 and 2 show an example of this rippling effect.

Definition

Any data structure can be reformulated in a retroactive setting. In general the data structure involves a series of updates and queries made over some period of time. Let U = [ut1, ut2, ut3, ..., utm] be the sequence of update operations from t1 to tm such that t1 < t2 < ... < tm. The assumption here is that at most one operation can be performed for a given time t.

Partially retroactive

We define the data structure to be partially retroactive if it can perform update and query operations at the current time and support insertion and deletion operations in the past. Thus for partially retroactive we are interested in the following operations:

- Insert(t, u): Insert a new operation u into the list U at time t.

- Delete(t): Delete the operation at time t from the list U.

Given the above retroactive operations, a standard insertion operation would now the form of Insert(t, "insert(x)"). All retroactive changes on the operational history of the data structure can potentially affect all the operations at the time of the operation to the present. For example, if we have ti-1 < t < ti+1, then Insert(t, insert(x)) would place a new operation, op, between the operations opi-1 and opi+1. The current state of the data structure (i.e.: the data structure at the present time) would then be in a state such the operations opi-1, op and opi+1 all happened in a sequence, as if the operation op was always there. See figure 1 and 2 for a visual example.

Fully retroactive

We define the data structure to be fully retroactive if in addition to the partially retroactive operations we also allow for one to perform queries about the past. Similar to how the standard operation insert(x) becomes Insert(t, "insert(x)") in the partially retroactive model, the operation query(x) in the fully retroactive model now has the form Query(t, "query(x)").

Retroactive running times

The running time of retroactive data structures are based on the number of operations, m, performed on the structure, the number of operations r that were performed before the retroactive operation is performed, and the maximum number of elements n in the structure at any single time.

Automatic retro-activity

The main question regarding automatic retro-activity with respect to data structures is whether or not there is a general technique which can convert any data structure into an efficient retroactive counterpart. A simple approach is to perform a roll-back on all the changes made to the structure prior to the retroactive operation that is to be applied. Once we have rolled back the data structure to the appropriate state we can then apply the retroactive operation to make the change we wanted. Once the change is made we must then reapply all the changes we rolled back before to put the data structure into its new state. While this can work for any data structure, it is often inefficient and wasteful especially once the number of changes we need to roll-back is large. To create an efficient retroactive data structure we must take a look at the properties of the structure itself to determine where speed ups can be realized. Thus there is no general way to convert any data structure into an efficient retroactive counterpart. Erik D. Demaine, John Iacono and Stefan Langerman prove this.[1]

See also

References

- Demaine, Erik D.; Iacono, John; Langerman, Stefan (2007). "Retroactive data structures". ACM Transactions on Algorithms. 3 (2): 13. doi:10.1145/1240233.1240236. S2CID 5555302. Retrieved 21 April 2012.