Revox B215

The Revox B215 is a cassette deck manufactured by Studer from 1985 until around 1990. A professional version with different control layout and audio path electronics was manufactured concurrently as the Studer A721. A later improved version was marketed as the Revox B215S. Because it was expensive compared to other consumer models and had exceptionally good mechanical performance and durability, the B215 was used primarily by professional customers—radio stations, recording studios and real-time[lower-alpha 1] cassette duplicators.

| Revox B215 | |

|---|---|

| Cassette deck | |

| |

| Manufacturer | Studer |

| Designers | Marino Ludwig Meinrad Liebert |

| Production period | 1985 – early 1990s |

| Features | Full four-motor direct drive Automatic calibration Dolby B and C Non-volatile memory |

The B215 used a proven, reliable four-motor tape transport derived from the earlier B710 model. The B215 differed from the B710 and competing decks of the period in having an unusual, computer-like control panel and elaborate automation performed by three Philips microcontrollers. The deck was equipped with automatic tape calibration, microcontroller-assisted setting of recording levels, and non-volatile memory.

Objective, independently measured and verified specifications of the Revox matched or surpassed those of the best competing decks; comparative tests placed the B215 on the same level as the Nakamichi Dragon and above the flagship models by ASC,[lower-alpha 2] Harman Kardon, Tandberg or TEAC. Reviewers praised the Revox for its exemplary mechanical quality and the expected durability of its tape transport, but criticized it for lower-than-expected dynamic range and shortcomings in usability.

Development and production

Studer AG, a privately owned Swiss manufacturer of professional audio equipment, began development of high fidelity cassette recorders in late 1970s. Willi Studer was reluctant to diversify into the highly competitive cassette deck market; for most of the decade, the company's experience in cassette technology was limited to reliable but low-fidelity classroom equipment.[1][2] However, the decline of reel-to-reel recorder sales, the commercial success of Nakamichi and "designer models" by Bang & Olufsen, coupled with pressure from within the company, persuaded Studer to invest in the cassette format.[2] Marino Ludwig, designer of the Revox B77 reel-to-reel recorder,[3] examined the best cassette decks on the market and advised Studer on a course of action.[2] Studer agreed with the proposal and appointed Ludwig chief of the cassette project, on the condition that the reputation of Studer and Revox brands would not be compromised in any way.[2]

In September 1980, Studer AG presented its first cassette deck, the Revox B710; in 1981 it was supplanted by the nearly identical Revox B710 MKII, which added Dolby C noise reduction. In 1982, the company introduced a professional version, the Studer A710, equipped with balanced inputs and outputs.[4] In the United States, the B710 MKII was priced at $1995,[5] more than the rival Nakamichi ZX7 ($1250) but below the flagship Nakamichi 1000ZXL ($3800 for the base version,[6] or $6000 for the "limited" edition.[7]) The three-head B710 was designed and built to the standards of professional reel-to-reel decks; even its faceplate and controls were borrowed from the B77 recorder.[2] The B710 stood apart from the competition in having a true, four-motor direct-drive tape transport: each of the two capstans and the two reels were driven by their own electric motor without any intermediate belts, gears or idlers.[2] There were no brake pads, belts, pulleys or cogwheels in the whole transport; even the tape counter was driven by an optoelectronic encoder on the reel motors. Mechanically separate recording and replay heads were each adjustable, however there was no user-accessible azimuth control. The B710 was mechanically sound but lacked functionality; most importantly, the deck lacked user-accessible tape calibration controls. Overall, the design was highly conservative.[1] Marino Ludwig wrote that the development coincided with a flood of new features (German: der Flut von Neuheiten) introduced by the Japanese, and only a few, like automatic tape type recognition, could be implemented within the deadline.[1] Untested novelties that could compromise the product, like dynamic biasing, were rejected from the start.[1]

In 1984 Ludwig and Meinrad Liebert designed a successor to B710, the B215.[2] The first pre-production batch was assembled at the end of 1984; the first production decks were shipped to dealers in the beginning of 1985.[8] A professional derivative, the Studer A721, was very similar to the B215 but was equipped with balanced inputs and outputs, and traditional rotary volume controls in place of up-down buttons. The press placed the B215 on a par with the best competing decks, rating its sound quality as high, or almost as high as that of the new reference deck—the Nakamichi Dragon. In the United States, the B215 was initially priced at "only" $1390,[9] lower than either the B710, or the Dragon. "Affordable" pricing and rugged transport made the B215 the deck of choice for real-time[lower-alpha 1] cassette duplicators; for example, by April 1986 Vermont-based Revolution Audio operated a fleet of 200 B215s, 24 hours a day, five days a week, and planned to purchase another 200.[10] German Audio magazine used a stack of ten B215's to duplicate its own test cassettes.[11]

Ludwig wrote that the price decrease reflected cost savings achieved through the use of larger printed circuit boards and automated assembly.[12] The introduction of the B215 also coincided with a record low Swiss franc exchange rate with the U.S. dollar, which hit an all-time low in February and March 1985.[13] Subsequently, the Swiss currency exchange rate increased consistently,[13] and so did Revox prices in North America. In 1989, the B215 was priced at $2400,[14] and in 1991, $2600.[15] The improved, cosmetically redesigned B215S, introduced in 1989, was priced at $2800–$2900[14][15]—more than the Dragon, and three to four times more than contemporary flagship decks by Onkyo, Pioneer or Sony.[15]

By this time Willy Studer had retired; in 1990 he sold the company and in 1994 it became a subsidiary of Harman International.[16] New Revox-branded cassette decks sold under Harman management, the consumer H11 and the professional C115,[17] were in fact rebadged Philips FC-60 / Marantz SD-60 models, and had nothing in common with the Revoxes of the past.[18] Classic flagship decks of the 1980s like the B215, the Dragon or the Tandberg 3014 were discontinued without replacement.[19] Further improvements in cassette sound, if possible at all, required substantial investment in research, but corporate resources were already committed to digital.[19]

Design and operation

Appearance and ergonomics

The B215, like all B-series Revoxes, is larger than the typical hi-fi component of the period.[20] The enclosure measures 45 by 15 by 33 centimetres (17.7 in × 5.9 in × 13.0 in)[20] and is a standard Studer pressed steel box with two internal stiffener rails that carry the tape transport.[21][22] The front panel design follows the B200-series styling, introduced in 1984 with the release of the B225 CD player.[23] Tape transport and recording mode controls, placed on the upper aluminum strip, are visually set aside from secondary buttons.[23] Loading the cassette into an open transport is performed in two moves: the upper edge of a cassette is inserted first, then the bottom of the cassette is pressed until it locks in place.[21] This presents no problem in everyday use.[21] Open tape transport is less prone to azimuth skew than typical closed-lid transports, and simplifies routine cleaning and demagnetization.[21][24]

Recording levels, recording balance and headphone volume are set electronically, with pairs of up/down buttons.[25][26] There are no microphone inputs; designers deemed those unnecessary for a consumer product.[22] The panel marking, according to Audio (USA) magazine reviewers, is exemplary: black letters on brushed aluminum and white letters on dark-grey plastic are large enough and easily readable at any angle of view.[27] The main backlit liquid-crystal display, on the contrary, is too small, too dim and too hard to read.[28][24] Another usability failure is the absence of front-panel control lights, even the critical 'Record On' red light is missing (it was later added to the Studer A721, but not the B215).[28] These quirks make it difficult to use the Revox in a darkened room.[28] Reviewers also noted the overall inconvenience of using digital control buttons instead of rotary potentiometers[24] (the latter, again, returned on the Studer A721 but not the Revox decks).

Tape transport

Typical double-capstan tape transport of the 1980s employed direct drive only for the leading (pulling) capstan;[29] the trailing (braking) capstan would be belt-driven at a slightly slower speed to provide tape tensioning inside the closed loop,[29] ensuring tight contact between all three heads and the tape (the cassette's pressure pad can only accommodate one head), and mechanically decoupling the tape from the cassette's shell.[29] A Revox deck works differently, directly driving each capstan with its own motor, equipped with a massive flywheel and a 150-pole speed sensor.[30] The speed of each motor is governed by a phase-locked loop; both loops are synchronized with a common crystal oscillator. According to Studer, each capstan was machined to a precision of 1 μm (0.001 mm or 0.000039 inch), to ensure very low wow and flutter.[31][lower-alpha 3] In 1985, the only other deck with a similar direct-drive arrangement was the five-motor Nakamichi Dragon (the nearest contender, the four-motor Tandberg 3014, used a single capstan motor).[32]

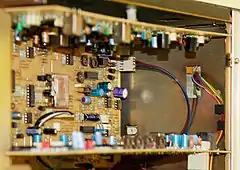

Two other motors of the B215, buried deep inside the mechanism, directly drive the cassette's reels. Motors, capstans and reel spindles are mounted on two diecast chassis plates, tightly bolted together; heads and pinch rollers are mounted on a moving die-cast subchassis.[31][33][lower-alpha 3] All four motors are braked electromagnetically; there are no mechanical brake pads or friction wheels.[33][lower-alpha 3] Autostop is triggered with an optoisolator which senses the presence of transparent leader tape.[27] Winding a 90-minute tape takes no more than 75 seconds,[20][28] at constant linear tape speed.[34] If, for any reason, the microcontroller detects abnormally high tape tension, it instantly reduces winding speed. At the end of the reel, tape speed is smoothly decreased to avoid end-of-tape impact.[34][22] According to Howard Roberson of Audio magazine (USA), operation of a new B215 transport "...was very quiet, even in play mode - perhaps the quietest of any deck ... tested to date... very well constructed, with a definite look of long-term reliability".[21]

The B215 uses sendust-and-ferrite heads made by Canon (the B710 used Sony heads, the Revox reel-to-reel heads were manufactured by Studer in-house).[35] Replay head has narrow magnetic gap, recording head has wide gap, but the exact widths of gaps were not disclosed.[2][22] Unlike the B710, the B215's recording and replay heads, and an isolation wedge between them, are tightly sandwiched together and may not be adjusted individually.[22] Reviewers of Audio and Modern Electronics noted exemplary low phase difference between left and right channels (interchannel time error, ICTE), which was a sign of very good alignment of recording and replay gaps and vanishingly low relative azimuth error.[36][37]

Audio path

The B215 signal path was designed, from the ground up, for operation with Dolby C noise reduction.[12] The owner's manual advised that "selecting noise reduction for new records is simple: use [only] Dolby C".[38] The deck uses four Hitachi HA12058 Dolby B/C ICs in "double Dolby" configuration with independent encoding and decoding channels.[39] Tape type is detected automatically, but the user can override and select the tape type manually. This includes an option of recording Type II (but not Type IV) tapes with 120 μs equalization,[40] which may be preferable for recording signals with strong treble content, at the cost of increased noise.[lower-alpha 4]

The B215 replay head amplifier used discrete JFET input and bipolar second stage; it drives the equalization stage—an active filter built around an operational amplifier in inverting configuration.[41] Subtle phase control networks in the active filter were tuned to best possible step response; Ludwig wrote that they enabled "square-wave reproduction off the tape of truly professional quality".[12] The signal then passes through a CMOS switch into the Dolby decoder, and then through another CMOS switch to output buffer stage.[41] A third set of CMOS switches engages to select 70 μs time constant instead of default 120 μs; as a result, during replay the signal passes through two or three CMOS switches, plus the switches inside the Dolby decoder.[41] The switches inevitably inject their own distortion products into the signal; their performance may be improved by replacement of stock 14000-series switches for newer pin-compatible low-impedance ICs. Line output level is fixed and is unusually "hot" for consumer audio: 775 mV RMS for nominal magnetization level of 250 nWb/m.[42] Headphone output has eight selectable volume settings, which is sufficient for practical use.[20]

Recording audio path, which occupies its own printed board, is far more complex. There are three electronic level controls, wired in series. Continuously variable fade-in and fade-out is performed by an analogue transconductance amplifier.[43] Signal levels at the input of Dolby encoder ("recording level") and at its output ("tape sensitivity") are controlled by 8-bit multiplying DACs.[43] Finally, a CMOS multiplexer, coupled to a low-Q bandpass filter centered on 4 kHz, selects the desired mid-range equalization setting.[43] Yet another set of 8-bit multiplying DACs, coupled to a non-defeatable Dolby HX Pro circuit, sets the desired bias current.[43] Dolby dynamic biasing, according to Stereo Review, improves treble saturation levels by about 6 dB.[44]

Microcontrollers and embedded software

The deck's control functions are spread between three identical Philips MAB8440 microcontrollers,[12] clocked with a common 6 Mhz crystal.[45] Each microcontroller carries 4 kB of program memory and 128 bytes of random-access memory.[45] The first microcontroller polls the faceplate keyboard, infrared remote control port, and an optically decoupled RS-232 port; the second one controls the motors and calculates real-time tape counter values. The third microcontroller manages the digital-to-analog converters, CMOS switches, multiplexers and recording level meter; it executes the tape calibration program and stores current settings in non-volatile memory.[12] The EEPROM is updated at every transition to standby mode, or when the user presses a dedicated "store" button.[46][47] The microcontrollers, display and DAC drivers are connected with the I²C serial bus,[45] which was introduced by Philips in the early 1980s; according to Ludwig, a standardized bus was a prerequisite for a project of such size.[12]

The B215 is equipped with a unique real-time tape counter.[48] After the user loads a cassette (rewound or not) and presses the "play" button, embedded software estimates the current tape position by comparing the angular speeds of cassette reels.[48] Initial estimation takes 5–8 seconds. The deck also estimates the complete playing time of a cassette, albeit with uncertainty; to decrease the margin of error, the user can set playing time manually to 46, 60, 90 or 120 minutes.[48] With this prompt, according to Audio magazine reviewers, absolute error does not exceed one minute for a C90 cassette.[20]

The B215's transport control software has a peculiar quirk that precludes complete rewinding of tape. After the deck completes rewinding, or after the user inserts an already rewound cassette, the B215 checks for the presence of opaque magnetic tape in the tape channel. If the optoelectronic sensor detects transparent leader tape, the deck slowly winds the tape forward until the sensor encounters opaque tape; this feature cannot be manually overridden. The deck is then ready for replay or recording, although performing auto-calibration at the very start of magnetic tape is undesirable; the operator should manually fast forward the tape to a random mid-reel point, perform calibration there and manually rewind back.[49][20]

Tape calibration

By 1985 tape calibration, absent in the Revox B710, became the de facto industry standard feature for top-of-the-line decks.[50][51] Reel-to-reel recorders did not need it because quarter-inch tape technology developed slowly, tapes on the market had very close magnetic and electroacoustical properties, and because high-speed recording was by design less sensitive to variations of tape properties.[50] Cassette tape technology, on the contrary, developed rapidly and newly designed premium formulations consistently differed from IEC references or the older, cheaper tapes.[50] The problem was already present in 1983: the B710, aligned at the factory to TDK SA-X ferricobalt Type II tape, had a pronounced treble droop when recording on pure chrome IEC Type II reference.[52]

Meinrad Liebert criticized the IEC for failing to impose strict standards: the organization simply followed the market, periodically adapting its set of reference tapes to arbitrarily chosen "industry averages".[50] Unchecked spread of incompatible cassettes made traditional fixed-bias decks almost unusable for recording; this, according to Liebert, explained sudden demand for calibration features that did not exist in the 1970s.[50] The Revox design team opted for automated calibration, although then-prevailing manual calibration was not only cheaper, but more robust as well. A human operator has an inherent advantage in handling inevitable dropouts, transients and slow fluctuations of the tape's sensitivity;[53][51] fully automatic calibration often failed to handle random irregularities and could generate different "optimum points" for the same tape.[53]

Of three or four calibration strategies available, Liebert chose the most flexible and robust constant treble equalization approach - adjusting bias and recording level while keeping recording channel equalization unchanged, with an additional frequency response adjustment at around 4 kHz.[53] Thus, unlike more common two-tone arrangement, the Revox used three test tones[12] (the exclusive Nakamichi 1000ZXL used four[7]). Although Studer preferred to name this function alignment, it only affects recording path electronics, and does not perform any mechanical alignment.[47] In spring of 1985, the calibration sequence was reverse-engineered by Audio magazine testers,[21] and two years later Liebert published first-hand description of the algorithm:

- Coarse adjustment of bias (17 kHz test tone);

- Sensitivity ("level") adjustment (400 Hz test tone);

- Fine adjustment of bias (17 kHz test tone);

- Midrange equalization adjustment (4 kHz test tone).[53]

The B215 adjusts bias and sensitivity separately in each channel, and midrange equalization is performed simultaneously in both channels.[54] Bias and sensitivity are set with 8-bit DACs using a binary search algorithm, so each of six adjustments takes up only eight elementary measurements.[53] At 400 Hz each measurement takes around 0.4 s: 0.1 s to advance the tape from recording head gap to replay head, and around 0.3 s to settle down the detector.[53] At 17 kHz, measurement takes even longer, because the test tone is recorded in short 120 ms bursts (to suppress unwanted crosstalk from the recording head to the replay head).[53] The complete test sequence, according to Liebert, takes around 25 s;[53] independent reviewers quoted even lower times of around 20 s. This was still much longer than the typical 4–8 seconds achieved by other auto-calibration decks of the same generation,[51] and close to the 30 s Liebert said would "strain the user's patience".[lower-alpha 5]

Tests and reviews

Independent measurements

Specifications published by Studer were highly conservative and did not reveal the deck's true potential.[55] Direct comparison with Japanese competitors was impossible, especially in tape transport parameters. For example, the B215's wow and flutter rating of 0.1% is a maximum value interpreted according to DIN 45507 / IEC 386,[56] while the competitors usually provided far lesser root mean square (RMS) numbers. Independent tests made by the press in the 1980s measured from 0.01% to 0.042% RMS, and from 0.016% to 0.07% maximum.[20][57][26][36][lower-alpha 6] Even the highest RMS value of 0.042% was considered "remarkably low";[36] the B215 either exceeded the competition or tied with the Nakamichi Dragon.[44][36][28][58] Craig Stark of Stereo Review admitted that the figures were so close to the limits of test instruments that any measured differences between the decks in this class were probably immaterial.[44] Long-term absolute speed, typically for all quartz-controlled double-capstan transports,[lower-alpha 7] was consistently 0.2–0.3% faster than standard, and almost insensitive to fluctuations in mains voltage.[20][26][57][28]

The dynamic range of the B215, understood as the difference between A-weighted bias noise level and maximum output level at 400 Hz, was on par with the Tandberg 3014, but consistently worse than that of the Dragon or the Onkyo 2900. The worst-case dynamic range, measured with quality Type I tape without noise reduction and spectral weighting, equaled only 51 dB compared to the Dragon's 54 dB. Both decks had about the same noise floor, determined by the tape's bias noise (hiss) rather than electronics; the Revox lost due to lower maximum output levels. According to Audio and Stereo Review tests, with Type I and Type IV tapes the B215 reached 3% distortion at only 3–4 dB above the Dolby level, while the Dragon could record and reproduce Type IV tapes all the way to +10 dB. Howard Roberson of Audio suggested that the narrow overload margin of the Revox was a price paid for its wide frequency response.[37]

The B215 user manual specified frequency response of 30–18000 Hz (+2/-3 dB) for Type I tapes and 30–20000 Hz (+2/-3 dB) for Types II and IV.[56] Again, independent tests revealed that performance far exceeded Studer's conservative specifications. Low-level frequency response, measured by Audio magazine at -20 dB relative to Dolby level, extends from 9–23100 Hz (± 3 dB) for Type I and Type IV tapes, and up to 24500 Hz (± 3 dB) for Type II tape.[37][lower-alpha 8] At Dolby level, where frequency response is limited mostly by tape saturation, rather than the deck, the Revox measured 23–14100 Hz for Type I, 23–16000 Hz for Type II and 24–17000 Hz for Type IV.[37][lower-alpha 8] The use of Dolby C extends the apparent upper boundary at Dolby level to 21–23 kHz.[37][lower-alpha 8] Overall, Revox treble extension is lower than the record set by the Nakamichi 1000ZXL (26–28 kHz[6]) but is typical for all flagship models of the mid-1980s.[55] The significance of this parameter was often overstated by hi-fi enthusiasts and the consumer-oriented press; professionals did not rate it as important because any professional deck easily exceeded the 20 kHz mark.[55] The quality of calibration, which is a prerequisite for good treble response, was rated very high;[20][44][28] the B215 easily "erased" differences between tapes as different as BASF CR-M (multilayer chrome, recommended by Studer[55][44]) and TDK SA (single-layer ferricobalt).[44]

The low frequency response of tapes recorded and replayed on the B215 has a prominent comb-like pattern below 30 Hz.[59][26][60] These "head bumps", indicating strong contour effect, appear only during recording.[21][61] Replay frequency response, measured with test tapes, is exemplararily flat,[21][61] on a par with the Nakamichi Dragon, and noticeably better than the Tandberg 3014.[61]

Overall evaluation

Reviewers between 1985 and 1988 unanimously gave the B215 excellent marks, particularly for the quality of its tape transport. Len Feldman of Modern Electronics wrote that "... on an overall basis ... it is, truly, a Rolls-Royce among cassette recorders. Its marque evades prestige. Moreover, it's built to last, and to go on meeting or exceeding all of its published specifications after many years of use."[28]

In comparative tests by Stereo Review (United States, 1988) and Audio (West Germany, 1985), the B215 was ranked one of the two best decks on the market, the other being the Nakamichi Dragon.[58][62] The B215 surpassed the Dragon in the mechanical department, having a simpler, robust, durable tape transport.[58] The B215 was losing to the Dragon in dynamic range and subjective level and the spectrum of noise; other subjectively detected differences in sonic signatures were insignificant and could be interpreted in favor of either contestant.[58] Sonically, both the B215 and the Dragon surpassed equally expensive ASC[lower-alpha 2] and Tandberg decks and the much cheaper flagship models by Harman Kardon, Onkyo and TEAC.[58][62]

The Dragon had an edge over the B215 and all other competitors in its automatic azimuth correction system.[63] The Dragon could easily "digest" tapes recorded on other, often misaligned, equipment.[63] Its six-channel, azimuth-sensing replay head remained a unicorn, an unprecedented pinnacle of cassette technology. Apart from a short-lived Marantz effort, no competitor ever tried to replicate it.[64] Production and aftermarket servicing of azimuth-sensing heads proved too difficult even for Nakamichi, and instead of developing the Dragon line, the company began production of unidirectional auto-reversing decks that physically flipped the cassette instead of reversing the transport.[64]

Notes

- Large-volume, low-cost cassette duplication employed industrial machines running at 16, 32 or even 64 times faster than normal. High-speed duplication was cheap, but detrimental to sound quality. A real-time duplicator would use normal, high quality cassette decks running at normal speed. These tapes could sound as good as cassette technology allowed, but real-time duplication was expensive and only suitable for small batches.

- ASC (Audio System Components) was a small German manufacturer of high fidelity domestic equipment, better known for their reel-to-reel recorders based on Braun transports. After the demise of high fidelity industry the company switched to industrial data recording services and, as of 2020, is still in business as ASC Technologies AG.

- Reference describes the B710

- Switching from 70 μs to 120 μs increases A-weighted noise level by around 4 dB, and increases apparent treble saturation level by the same 4 dB. Actual saturation level, in terms of tape magnetization, remains unchanged, but its apparent level is boosted by equalization filter.

- Liebert wrote that anything exceeding 30 s will "strain the user's patience".[53]

- In each and every case, the numbers characterized one particular sample; these numbers are mere indicators of the deck's performance, and do not apply to the whole population.

- Manufacturers intentionally made new decks 0.2–0.5% faster than standard. As the decks aged, capstan wear gradually reduced speed back to standard. Small increases in speed were deemed far less detrimental than small decreases.

- In all cases, Audio magazine used top-of-the-line, expensive tape formulations - Maxell UD-XLI, TDK HX-S, TDK MA-R.[37] The Type II TDK HX-S was, in fact, a metal particle tape designed to operate at Type II bias. Testers deliberately selected the tapes producing best results with the B215, while other premium formulations did not perform just as good.[37]

References

- Ludwig 1981, p. 3.

- Guzman, Carlos (2018). "The Revox B215". Retrieved 2019-04-22. Author is the owner/operator of recording and tape duplication studios, member of The Legends.

- Ziemann 1990, p. 10.

- Zogg 1982, pp. 4–5.

- Riggs 1983a, p. 20.

- Roberson, Howard (1981). "Nakamichi 1000ZXL Cassette Deck". Audio (USA) (June): 54.

- Berger, Ivan (1982). "The world's most expensive cassette deck". Audio (USA) (September): 42–43.

- "New Products: Revox". Stereo Review (March / Special Tape Issue): 9. 1985.

- Stereo Review staff (March 1985). "New Products: Revox". Stereo Review (March): 9.

- Dupler, Steven (1986). "Sound Investment: Real-Time by Revox". Billboard. No. April 5. p. 57.

- Siegenthaler 1990, p. 2.

- Ludwig 1985, p. 9.

- "Switzerland / U.S. Foreign Exchange Rate (EXSZUS)". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

- Stereo Review staff (March 1989). "New Products: Revox". Stereo Review (March): 18.

- Stereo Review staff (March 1991). "Tape Buying Guide. Tape Recorders". Stereo Review (March): 66–71.

- Jones, Sarah (2018). "Studer at 70". Mixonline.com.

- Revox C115 Professional Cassette Tape Deck. Regensdorf-Zurich: Studer (a Harman International Company). 1995.

- "Кассетные деки. Revox". Inthouse.ru. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- Stark 1988, p. 52.

- Roberson 1985, p. 52.

- Roberson 1985, p. 48.

- Stark 1986, p. 40.

- Ludwig 1985, p. 8.

- Warren, Rich (1986). "Revox cassette deck: Mercedes look, Jeep ruggedness". Chicago Tribune (February).

- Feldman 1986, p. 14.

- Stark 1986, p. 42.

- Roberson 1985, p. 45.

- Feldman 1986, p. 100.

- Stark, Craig (1985). "Akai GX-9 Cassette Deck". Stereo Review (December): 44.

- Willi Studer AG 1985b, Section 4.4. С-Motor.

- Hopker 1981, p. 4.

- Petras, Fred (1985). "Cassette Desks. What are your options?" (PDF). Stereo Review (December): 76.

- Siegenthaler 1980, p. 2.

- Studer/Revox USA (1986). "Revox cassette transport turns pro" (PDF). Audio (August): 68.

- "Revox B710 / B710 MKII". The Vintage Knob. 2012. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- Feldman 1986, p. 18.

- Roberson 1985, p. 50.

- Willi Studer AG 1985a, Section 3.3. Which noise reduction?.

- Willi Studer AG 1985b, Section 4.6. NR System.

- Willi Studer AG 1985a, Section 3.1. Preparation for recording.

- Willi Studer AG 1985b, Section 7.13.

- Willi Studer AG 1985a, Section 7.4 Technical Data.

- Willi Studer AG 1985b, Section 4.7 Record Control, Section 7.9.

- Stark 1986, p. 44.

- Willi Studer AG 1985b, Section 4.3. System control.

- Ludwig 1985, pp. 8–9.

- Roberson 1985, p. 46.

- Roberson 1985, pp. 45, 46.

- Willi Studer AG 1985a, Section 3.4. Automatic alignment, subsecton Note.

- Liebert 1987, p. 4.

- Hirsch, Julian (1984). "Tape Recording: State of the Art". Stereo Review (Tape Recording and Buying Guide): 9.

- Riggs 1983a, p. 23.

- Liebert 1987, p. 5.

- Liebert 1987, p. 6.

- Feldman 1986, p. 15.

- Willi Studer AG 1985a, Section 7.4. Technical Data.

- Stark 1988, p. 56.

- Stark 1988, p. 58.

- Roberson 1985, p. 49.

- Stark 1986, p. 57.

- Stark 1988, pp. 57–58.

- Feld 1985, p. 84.

- Riggs 1983b.

- Sabin, Rob (2018). "Vintage Test Report: Nakamichi Dragon Cassette Deck. Introduction". Sound & Vision (October 2). Preface to an online reprint of Craig Stark's 1983 review

Sources

Reviews

- Feldman, Len (1986). "The Revox B215 — An Elegant Cassette Deck From Swiss Craftsmen". Modern Electronics (June): 15–20, 100.

- Hirsch, Julian (1984). "Revox B710 MkII Cassette Deck". Stereo Review (Tape Recording and Buying Guide): 44–46.

- Riggs, Michael (1983a). "Revox's Pro-Am Cassette Deck". High Fidelity (February): 20–24.

- Riggs, Michael (1983b). "Auto-Azimuth. Nakamichi scores another first" (PDF). High Fidelity (April): 28–32.</ref>

- Roberson, Howard (1985). "Revox B215 Cassette Deck". Audio (USA) (July): 44–52.

- Stark, Craig (1986). "Revox B215 Cassette Deck". Stereo Review (August): 40–44.

Comparative tests

- Feld, Wolfgang (1985). "Alle mal herhören. Vergleichsest: acht Rekorder von 2000 bis 4500 Mark". Audio (Germany) (in German) (Juni): 78–84.

- Stark, Craig (1988). "5 Top Tape Decks". Stereo Review (March): 52–58.

Manufacturer's publications

- Ludwig, Marino (1981). "Revox B710 Microcomputer Controlled Cassette Tape Deck" (PDF). Studer Revox Print (in German) (39): 3.

- Hopker, Rudolf (1981). "Revox B710 in der Fertigung" (PDF). Studer Revox Print (in German) (39): 4–5.

- Ludwig, Marino (1985). "B215, the new Revox cassette tape recorder. Intelligent precision" (PDF). Swiss Sound (11): 8–9.

- Liebert, Meinrad (1987). "Revox B215 automatic calibration. The perfect compromise" (PDF). Swiss Sound (19): 4–6.

- Siegenthaler, Marcel (1980). "Neu: Revox B710 Microcomputer Controlled Cassette Tape Deck" (PDF). Studer Revox Print (36): 2.

- Siegenthaler, Marcel (1990). "Sound Check. Revox B215 for test cassette production" (PDF). Swiss Sound (29): 2.

- Willi Studer AG (1985a). Revox B215 Bedienungsanleitung / Operating Instructions / Mode d'emploi (in German, English, and French). Regensdorf, Zurich: Willy Studer AG.

- Willi Studer AG (1985b). Revox B215 Serviceanleitung / Service Instructions / Instructions de service (in German, English, and French). Regensdorf, Zurich: Willy Studer AG.

- Willi Studer AG (1986). Studer A721 Bedienuings- und Serviceanleitung / Operating and Service Instructions (in German, English, and French). Regensdorf, Zurich: Willy Studer AG.

- Ziemann, Renate (1990). "Who's Who: Marino Ludwig" (PDF). Swiss Sound (28): 10.

- Zogg, Urs (1982). "Studer A710 - the cassette recorder that is different" (PDF). Swiss Sound (2): 4–5.