Rhiannon

Rhiannon is a major figure in Welsh mythology, appearing in the First Branch of the Mabinogi, and again in the Third Branch. Ronald Hutton called her "one of the great female personalities in World literature", adding that "there is in fact, nobody quite like her in previous human literature".[1] In the Mabinogi, Rhiannon is a strong-minded Otherworld woman, who chooses Pwyll, prince of Dyfed (west Wales), as her consort, in preference to another man to whom she has already been betrothed. She is intelligent, politically strategic, beautiful, and famed for her wealth and generosity. With Pwyll she has a son, the hero Pryderi, who later inherits the lordship of Dyfed. She endures tragedy when her newborn child is abducted, and she is accused of infanticide. As a widow she marries Manawydan of the British royal family, and has further adventures involving enchantments.

Like some other figures of British/Welsh literary tradition, Rhiannon may be a reflection of an earlier Celtic deity. Her name appears to derive from the reconstructed Brittonic form *Rīgantonā, a derivative of *rīgan- "queen". In the First Branch of the Mabinogi, Rhiannon is strongly associated with horses, and so is her son Pryderi. She is often considered to be related to the Gaulish horse goddess Epona.[2][3] She and her son are often depicted as mare and foal. Like Epona, she sometimes sits on her horse in a calm, stoic way.[4] This connection with Epona is generally accepted among scholars of the Mabinogi and Celtic studies, but Ronald Hutton, a historian of paganism, is skeptical.[5]

Rhiannon's story

Y Mabinogi: First Branch

Rhiannon first appears at Gorsedd Arberth, an ancestral mound near one of the chief courts of Dyfed. Pwyll, the prince of Dyfed, has accepted the challenge of the mound's magical tradition to show a marvel or deal out blows. Rhiannon appears to him and his court as the promised marvel. She is a beautiful woman arrayed in gold silk brocade, riding a shining white horse. Pwyll sends his best horsemen after her two days running, but she always remains ahead of them, though her horse never does more than amble. On the third day he finally follows her himself and does no better, until he finally appeals to her to stop for him.

Rhiannon characteristically rebukes him for not considering this course before, then explains she has sought him out to marry him, in preference to her current betrothed, Gwawl ap Clud. Pwyll gladly agrees, but at their wedding feast at her father's court, an unknown man requests Pwyll grant a request; which he does without asking what it is. The man is Gwawl, and he requests Rhiannon.

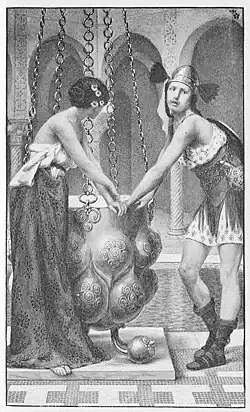

Rhiannon rebukes Pwyll a second time for his rash promise, but provides the means and the plan to salvage the situation. She holds a second wedding feast for Gwawl, where she deploys Pwyll's men outside in the orchard. She instructs Pwyll to enter the hall dressed as a beggar and humbly request Gwawl fill a certain 'small bag' with food. But she has enchanted the 'small bag' so it cannot ever be filled by normal means. Gwawl is persuaded to step in it to control its magic, which means Pwyll can trap him in it. Pwyll's men rush in and surround the hall, then beat and kick Gwawl as the Badger-in-the-Bag game. To save his life Gwawl is forced to relinquish Rhiannon completely, and also his revenge. Rhiannon marries Pwyll, then journeys to Dyfed as its queen.

After a happy two years, Pwyll comes under pressure from his nobles, to provide an heir. He refuses to set Rhiannon aside as barren, and in the third year their son is born. However, on the night of his birth, the newborn disappears while in the care of Rhiannon's six sleepy maids. Terrified of being put to death, the women kill a puppy and smear its blood on Rhiannon's sleeping face. In the morning they accuse her of infanticide and cannibalism. Rhiannon takes counsel with her own advisers, and offers to undergo a penance. Pwyll is again urged to set her aside, but refuses, and sets her penance instead. She must sit every day by the gate of the castle at the horse block, to tell her story to travelers. She must also offer to carry them on her back as a beast of burden, though few accept this. However, as the end of the story shows, Pwyll maintains her state as his queen, as she still sits at his side in the hall at feasting time.

The newborn child is discovered by Teyrnon, the lord of Gwent-Is-Coed (South-Eastern Wales). He is a horse lord whose fine mare foals every May Eve, but the foals go missing each year. He takes the mare into his house and sits vigil with her. After her foal is born he sees a monstrous claw trying to take the newborn foal through the window, so he slashes at the monster with his sword. Rushing outside he finds the monster gone, and a human baby left by the door. He and his wife claim the boy as their own naming him Gwri Wallt Euryn (Gwri of the Golden Hair), for "all the hair on his head was as yellow as gold".[6] The child grows at a superhuman pace with a great affinity for horses. Teyrnon who once served Pwyll as a courtier, recognises the boy's resemblance to his father. As an honourable man, he returns the boy to the Dyfed royal house.

Reunited with Rhiannon the child is formally named in the traditional way via his mother's first direct words to him Pryderi a wordplay on "delivered" and "worry", "care", or "loss". In due course Pwyll dies, and Pryderi rules Dyfed, marrying Cigfa of Gloucester, and amalgamating the seven cantrefs of Morgannwg to his kingdom.

Y Mabinogi: Third Branch

Pryderi returns from the disastrous Irish wars as one of the only Seven Survivors. Manawydan is another Survivor, and his good comrade and friend. They perform their duty of burying the dead king of Britain's head in London (Bran the Blessed) to protect Britain from invasion. But in their long time away, the kingship of Britain has been usurped by Manawydan's nephew Caswallon.

Manawydan declines to make more war to reclaim his rights. Pryderi recompenses him generously by giving him the use of the land of Dyfed, though he retains the sovereignty. Pryderi also arranges a marriage between the widowed Rhiannon and Manawydan, who take to each other with affection and respect. Pryderi is careful to pay homage for Dyfed to the usurper Caswallon to avert his hostility.

Manawydan now becomes the lead character in the Third Branch, and it is commonly named after him. With Rhiannon, Pryderi and Cigfa, he sits on the Gorsedd Arberth as Pwyll had once done. But this time disaster ensues. Thunder and magical mist descend on the land leaving it empty of all domesticated animals and all humans apart from the four protagonists.

After a period of living by hunting the four travel to borderland regions (now in England) and make a living at skilled crafts. In three different cities they build successful businesses making saddles, shields, then shoes. But vicious competition puts their lives at risk. Rather than fight as Pryderi wishes, Manawydan opts to quietly move on. Returning to Dyfed, Manawydan and Pryderi go hunting and follow a magical white boar, to a newly built tower. Against Manawydan's advice, Pryderi enters it to fetch his hounds. He is trapped by a beautiful golden bowl. Manawydan returns to Rhiannon who rebukes him sharply for failing to even try to rescue his good friend. But her attempt to rescue her son suffers the same fate as he did. In a "blanket of mist", Rhiannon, Pryderi and the tower vanish.

Manawydan eventually redeems himself by achieving restitution for Rhiannon, Pryderi, and the land of Dyfed. This involves a quasi-comical set of magical negotiations about a pregnant mouse. The magician Llwyd ap Cilcoed is forced to release both land and family from his enchantments, and never attack Dyfed again. His motive is revealed as vengeance for his friend Gwawl, Rhiannon's rejected suitor. All ends happily with the family reunited, and Dyfed restored.

Interpretation as a goddess

When Rhiannon first appears she is a mysterious figure arriving as part of the Otherworld tradition of Gorsedd Arberth. Her paradoxical style of riding slowly, yet unreachably, is strange and magical, though the paradox also occurs in mediaeval love poetry as an erotic metaphor. Rhiannon produces her "small bag" which is also a magical paradox for it cannot be filled by any ordinary means. When undergoing her penance, Rhiannon demonstrates the powers of a giantess, or the strength of a horse, by carrying travellers on her back.

Rhiannon is connected to three mystical birds. The Birds of Rhiannon (Adar Rhiannon) appear in the Second Branch, in the Triads of Britain, and in Culhwch ac Olwen. In the latter, the giant Ysbaddaden demands them as part of the bride price of his daughter. They are described as "they that wake the dead and lull the living to sleep." This possibly suggests Rhiannon is based on an earlier goddess of Celtic polytheism.

W. J. Gruffydd's book Rhiannon (1953) was an attempt to reconstruct the original story. It is mainly focused on the relationship between the males in the story, and rearranges the story elements too liberally for other scholars' preference, though his research is otherwise detailed and helpful. Patrick Ford suggests that the Third Branch "preserves the detritus of a myth wherein the Sea God mated with the Horse Goddess."[7] He suggests "the mythic significance may well have been understood in a general way by an eleventh century audience." Similar euhemerisms of pre-Christian deities can be found in other medieval Celtic literature, when Christian scribes and redactors reworked older deities as more acceptable giants, heroes or saints. In the Táin Bó Cúailnge, Macha and The Morrígan similarly appear as larger-than-life figures, yet never described as goddesses.

Proinsias Mac Cana's position is that "[Rhiannon] reincarnates the goddess of sovereignty who, in taking to her a spouse, thereby ordained him legitimate king of the territory which she personified."[8] Miranda Green draws in the international folklore motif of the calumniated wife, saying, "Rhiannon conforms to two archetypes of myth ... a gracious, bountiful queen-goddess; and ... the 'wronged wife', falsely accused of killing her son."[9]

Modern interpretations

Rhiannon appears in many retellings and performances of the Mabinogi (Mabinogion) today. There is also a vigorous culture of modern fantasy novels.[10] These include Not For All The Gold In Ireland (1968) by John James, where Rhiannon marries the Irish god Manannan.[11] Rhiannon also appears in The Song of Rhiannon (1972) by Evangeline Walton, which retells the Third Branch of the Mabinogion.[12]

Leigh Brackett used the name Rhiannon in her Planetary romance novel The Sword of Rhiannon (1949); in this book Rhiannon is the name of a powerful male Martian.[13]

An example of a modern Rhiannon inspiration is the Fleetwood Mac song "Rhiannon" (1975). Stevie Nicks was inspired to create the song after reading Triad: A Novel of the Supernatural, a novel by Mary Bartlet Leader. There is mention of the Welsh legend in the novel, but the Rhiannon in the novel bears little resemblance to her original Welsh namesake. Nevertheless, despite having little accurate knowledge of the original Rhiannon, Nicks' song does not conflict with the canon, and quickly became a musical legend.[14]

In artworks, Rhiannon has inspired some entrancing images. A notable example is Alan Lee 1987, and 2001, who illustrated two major translations of the Mabinogi, and his pictures have attracted their own following.

In the Robin of Sherwood story "The King's Fool" (1984), Rhiannon's Wheel is the name of a stone circle where Herne the Hunter appears to the characters.[15]

Rhiannon is included in various Celtic neopaganism traditions since the 1970s, with varying degrees of accuracy in respect to the original literary sources.

In the fantasy world of Poul Anderson's Three Hearts and Three Lions, there is a "University of Rhiannon", where Magic is taught.

References

- Hutton, Ronald. "Finding Lost Gods in Wales". YouTube. Gresham College. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Ford, Patrick K. (12 February 2008). The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520253964 – via Google Books.

- e.g. Sioned Davies (trans.), The Mabinogion, Oxford 2007, p. 231.

- Gruffydd, W. J. Rhiannon: An Inquiry into the Origins of the First and Third Branches of the Mabinogi

- Hutton, Ronald (2014). Pagan Britain. Yale University Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-0300197716.

- The Mabinogion. Davies, Sioned. 2005.

- Patrick K. Ford, The Mabinogi and Other Medieval Welsh Tales (1977).

- Mac Cana, p. 56.

- Green, p. 30.

- Sullivan, Charles William III. "Conscientious Use: Welsh Celtic Myth and Legend in Fantastic Fiction.” Archived 8 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine Celtic Cultural Studies, 2004.

- David V. Barrett, "James, John" in St. James Guide To Fantasy Writers, edited by David Pringle. St. James Press, 1996, ISBN 9781558622050 (pp. 308-9) .

- Cosette Kies, "Walton, Evangeline" in St. James Guide To Fantasy Writers, edited by David Pringle. St. James Press, 1996, ISBN 9781558622050 (pp. 586-7) .

- Michael Moorcock and James Cawthorn, Fantasy: The 100 Best Books. Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, 1991. ISBN 9780881847086 (pp. 157-158).

- "Stevie Nicks on Rhiannon". inherownwords. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- Richard Carpenter, Robin of Sherwood. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England : Puffin Books, 1984 ISBN 9780140316902 (pp. 157-8)

Sources

- William J. Gruffydd (1953). Rhiannon. Cardiff.

- Jones, Gwyn and Jones, Thomas. "The Mabinogion ~ Medieval Welsh Tales." (Illust. Alan Lee). Dragon's Dream., 1982.

- Guest, Charlotte. "The Mabinogion." (Illust. Alan Lee). London and NY.: Harper Collins., 2001.

- MacKillop, James (2004). "Rhiannon" in A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198691570

- Sullivan, Charles William III. "Conscientious Use: Welsh Celtic Myth and Legend in Fantastic Fiction.” Celtic Cultural Studies, 2004. See here

External links

- Parker, Will. "Mabinogi Translations." Mabinogi Translations, 2003. Reliable online text extremely useful for fast lookup, or copying quotes. See here

- Story of Rhiannon