Richard Seddon

Richard John Seddon PC (22 June 1845 – 10 June 1906) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 15th premier (prime minister) of New Zealand from 1893 until his death. In office for thirteen years, he is to date New Zealand's longest-serving head of government.

Richard John Seddon | |

|---|---|

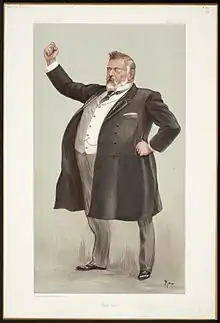

Seddon in 1905 | |

| 15th Prime Minister of New Zealand[* 1] | |

| In office 27 April 1893 – 10 June 1906 | |

| Monarchs | Victoria Edward VII |

| Governor | David Boyle Uchter Knox William Plunket |

| Preceded by | John Ballance |

| Succeeded by | William Hall-Jones |

| 8th Minister of Defence | |

| In office 23 January 1900 – 10 June 1906 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Thomas Thompson |

| Succeeded by | Albert Pitt |

| In office 24 January 1891 – 22 June 1896 | |

| Prime Minister | John Ballance |

| Preceded by | William Russell |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Thompson |

| 11th Minister of Public Works | |

| In office 24 January 1891 – 2 March 1896 | |

| Prime Minister | John Ballance |

| Preceded by | Thomas Fergus |

| Succeeded by | William Hall-Jones |

| 7th Minister of Mines | |

| In office 24 January 1891 – 6 September 1893 | |

| Prime Minister | John Ballance |

| Preceded by | Thomas Fergus |

| Succeeded by | Alfred Cadman |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Westland | |

| In office 5 December 1890 – 10 June 1906 | |

| Preceded by | Electorate created |

| Succeeded by | Tom Seddon |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Kumara | |

| In office 9 December 1881 – 5 December 1890 | |

| Preceded by | Electorate created |

| Succeeded by | Electorate abolished |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Hokitika | |

| In office 5 September 1879 – 9 December 1881 | |

| Preceded by | Multi-member electorate |

| Succeeded by | Gerard George Fitzgerald |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 June 1845 Eccleston, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 10 June 1906 (aged 60)[2] At sea |

| Resting place | Bolton Street Memorial Park |

| Political party | Independent (1879–91) Liberal (1891–1906) |

| Spouse | Louisa Jane Spotswood (m. 1869) |

| Children | 9, including Tom Seddon and Elizabeth Gilmer |

| Signature |  |

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

General elections |

||

Seddon was born in Eccleston near St Helens, Lancashire, in England. He arrived in New Zealand in 1866 to join an uncle in the West Coast goldfields.[3] His prominence in local politics gained him a seat in the House of Representatives in 1879. Seddon became a key member of the Liberal Party under the leadership of John Ballance, but differed from him greatly due to his conservativism clashing with Ballance's progressivism. When the Liberal Government came to power in 1891 Seddon was appointed to several portfolios, including Minister of Public Works. His natural leadership and confrontational manner, however, led him to quickly rise to become the man who would control the fate of the Liberal Party itself.

Seddon succeeded to the leadership of the Liberal Party following Ballance's death in 1893, inheriting a bill for women's suffrage, which was passed the same year despite Seddon's opposition to it. Seddon's government achieved many social and economic changes, such as the introduction of old age pensions. His personal popularity, charisma and strength overcame dissent from within his cabinet, with Seddon defeating a leadership challenge from Robert Stout, a progressive longtime ally of the deceased Ballance who was himself Ballance's chosen successor.[4] This has been described as firmly establishing "Seddonism", a colloquial term for Seddon's strand of nationalist conservatism, as New Zealand's dominant political ideology.[5] His government also purchased vast amounts of land from the Māori, aided by his allies Alfred Cadman and James Carroll as the Ministers of Native Affairs. He spent the 1899 general election trying to relieve New Zealand's parliament of the independent politicians who had so greatly dominated the country's organised national politics since its provenance, in which he triumphed greatly.[5] An imperialist in foreign policy, his attempt to incorporate Fiji into New Zealand failed, but he successfully annexed the Cook Islands in 1901. Seddon's government supported Britain with troops in the Second Boer War (1899–1902) and supported preferential trade between British colonies. Seddon was the second New Zealand head of government to die in office, after his predecessor Ballance.

Seddon was regarded as deeply regionalist; the late Professor of History at Victoria University of Wellington, D.A. Hamer, described him as "an intensely parochial politician...a great fighter for the interests of West Coasters but with no interest in or knowledge about wider New Zealand problems".[5] His heritage from the region defined him not only as a politician, but as a man; he became well-known for the "uncouth" stereotypes of the generally West Coast Pākehā population of the time, expressed in his lack of education, boisterous and aggressive persona, and his dialectal tendency to drop his aitches. Seddon continued to live on the West Coast of the South Island throughout his premiership, only coming to Wellington on a regular basis very reluctantly, from the late 1890s. Seddon was also described as a man of secret brooding, who secretly battled anxiety and depression beneath his public surface of rodomontade and bravado; he hid his personal struggles to ensure his enemies would not feel pleasure knowing they had hurt him.[5]

Despite his personal insecurities, dominating and almost illiberal viewpoints, and erratic nature, he inspired serious and long-lasting loyalty among his cabinet members. Leading the Liberal Party until his death, the party afterwards struggled to recover, going through a string of leaders before essentially giving way to New Zealand's modern two-party system of what would become the Labour and National Parties.[5] Ironically, this was something Seddon had been instrumental in creating, through his successful attempt at suppressing New Zealand's previously dominant political cohort of independents.[5]

Despite being derisively known as "King Dick" for his autocratic style,[3] and criticised for his actions on Māori land deprivation and his views on race (especially towards Chinese), he has nonetheless been named as one of the greatest, most influential, and most widely known politicians in New Zealand history.

Early life and family

Seddon was born in the town of Eccleston, near St Helens in Lancashire, England, on 22 June 1845.[6] His father Thomas Seddon (born 1817) was a school headmaster, and his mother Jane Lindsay was a teacher; they married on 8 February 1842 at Christ Church, Eccleston. Richard was the third of their eight children.

Despite this background, Seddon did not perform well at school, and was described as unruly. Despite his parents' attempt to give him a classical education, Seddon developed an interest in engineering, but was removed from school at age 12. After working on his grandfather Richard's farm at Barrow Nook Hall for two years,[7] Seddon was an apprentice at Daglish's Foundry in Sutton. He later worked at Vauxhall foundry in Liverpool,[3] where he attained a Board of Trade Certificate as a mechanical engineer.[8] During his time in Lancashire, he was heavily influenced by social liberalism, and many of its ideas would form part of his political philosophy as a politician.[9]

On 15 June 1862, at the age of 16, Seddon decided to emigrate to Australia, working his passage to Melbourne on the SS Great Britain.[10] He later provided his reasoning: "A restlessness to get away to see new, broad lands seized me: My work was irksome. I felt cramped."[11] He entered the railway workshops at Williamstown, and also worked in the goldfields at Bendigo; he did not meet with any great success. In either 1865 or 1866, he became engaged to Louisa Jane Spotswood, but her family would not permit marriage until Seddon was financially secure.

Seddon moved to New Zealand's West Coast in 1866. Initially, he worked the goldfields in Waimea. He is believed to have prospered here, and he returned briefly to Melbourne to marry Louisa. He established a store, and then expanded his business to include the sale of alcohol, becoming a publican. He was followed to the West Coast by his older sister Phoebe, younger brothers Edward and Jim and younger sister Mary.[12] Phoebe married William Cunliffe on 9 May 1863 at Holy Trinity Church Eccleston. Their son Bill was Labour MP David Cunliffe's grandfather, making Richard Seddon David Cunliffe's great-great-uncle.[13]

Local politics

Seddon first entered politics in 1870, when he ran unsuccessfully for the Westland County Council, finishing third. The same year, he was elected to the Arahura Road Board. He ran again for the County Council in 1872, finishing a distant third.[14]

In 1874 Seddon stood for the newly created Westland Provincial Council and was elected for Arahura. He established himself as a broadly effective, if rather bellicose, advocate for miners' interests. He also took an interest in education during this time.[15] He lost this position with the abolition of the provinces in 1876, and was elected instead to the newly reconstituted county council.[16][17] In 1876 he stood for Parliament in the two-member Hokitika electorate and placed fourth out of five candidates.[18][19]

Kumara became a prominent goldmining town. Seddon was elected its first Mayor in 1877. He had staked a claim in Kumara the previous year, and had shortly afterwards moved his business there. Despite occasional financial troubles (he filed for bankruptcy in 1878[20]), his political career prospered.

Entry to Parliament

In the 1879 election, he stood for Parliament again, and was elected. He represented Hokitika to 1881, then Kumara from 1881 to 1890, then Westland from 1890 to his death in 1906. His son Tom Seddon succeeded him as MP for Westland.

In Parliament, Seddon aligned himself with George Grey, a former Governor turned Premier. Seddon later claimed to be particularly close to Grey, although some historians believe that this was an invention for political purposes. Initially, Seddon was derided by many members of Parliament, who mocked his "provincial" accent (which tended to drop the letter "h") and his lack of formal education. He nevertheless proved quite effective in Parliament, being particularly good at "stonewalling" certain legislation. His political focus was on issues of concern to his West Coast constituents. He specialised on mining issues, became a recognised authority on the topic, and chaired the goldfields committee in 1887 and 1888.[21]

He aggressively proclaimed a populist anti-elitist philosophy in many speeches and toast. "It is the rich and the poor; it is the wealthy people and the landowners against the middle classes and the labouring classes," he explained.[22]

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1879–1881 | 7th | Hokitika | Independent | ||

| 1881–1884 | 8th | Kumara | Independent | ||

| 1884–1887 | 9th | Kumara | Independent | ||

| 1887–1890 | 10th | Kumara | Independent | ||

| 1890–1893 | 11th | Westland | Liberal | ||

| 1893–1896 | 12th | Westland | Liberal | ||

| 1896–1899 | 13th | Westland | Liberal | ||

| 1899–1902 | 14th | Westland | Liberal | ||

| 1902–1905 | 15th | Westland | Liberal | ||

| 1905–1906 | 16th | Westland | Liberal | ||

Liberal Party

Seddon joined the nascent Liberal Party, led by John Ballance, following the December 1890 general election. Their platform was for reform in the areas of land and labour.[23] They were greatly helped by the abolition of plural voting, which allowed landowners in each district they owned land in to vote in them.[23]

Seddon was sworn into his first ministerial positions when the Liberals came to power in January 1891.[3] He became minister of public works, mines, defence, and marine. He promoted co-operative contract system for road-making and other public works projects.

Unlike Ballance who believed in classical liberalism, Seddon did not have any great commitment to any ideology. Rather, he saw the Liberals as champions of "the common man" against large commercial interests and major landowners.[24] His strong advocacy for what he saw as the interests of ordinary New Zealanders won him considerable popularity. Attacks by the opposition, which generally focused on his lack of education and sophistication (one opponent said that he was only "partially civilised") reinforced his growing reputation as an enemy of elitism.[24]

Seddon quickly became popular across the country. Some of his colleagues, however, were not as happy, accusing him of putting populism ahead of principle, and of being an anti-intellectual. John Ballance, now Premier, had a deep commitment to liberal causes such as women's suffrage and Māori rights, which Seddon was not always as enthusiastic about. Nevertheless, many people in the Liberal Party believed that Seddon's popularity was a huge asset for the party, and Seddon developed a substantial following.

Premiership

Ballance fell seriously ill in 1892 and made Seddon acting leader of the House. After Ballance's death in April 1893, the Governor David Boyle, 7th Earl of Glasgow asked Seddon, as the acting leader of the house, to form a new ministry. Despite the refusal of William Pember Reeves and Thomas Mackenzie to accept his leadership, Seddon managed to secure the backing of his Liberal Party colleagues as interim leader, with an understanding being reached that a full vote would occur when Parliament resumed sitting.[25] Seddon's most prominent challenger was Robert Stout, a former Premier for two separate terms. Like Ballance, Stout had a strong belief in classical-liberal principles. Ballance himself had preferred Stout as his successor,[26] but had died before being able to secure this aim. Stout was not a member of the House of Representatives at the time of Ballance's death, and only re-entered following the by-election in Inangahua on 8 June 1893.

Despite Seddon's promise, however, there was no vote on the party leadership and therefore the premiership. By convincing his party colleagues that a leadership contest would split the party in two, or at least leave deep divisions, Seddon managed to secure a permanent hold on the leadership.[25] Stout continued to be one of his strongest critics and led the campaign for women's suffrage despite Seddon's opposition. Eventually Stout left the Liberal Party in 1896 and remained in the house as an independent until 1898. In 1899 however, Seddon recommended Stout to the Governor as the next Chief Justice of New Zealand.

Women's suffrage

John Ballance, founder of the Liberal Party, had been a strong supporter of voting rights for women, declaring his belief in the "absolute equality of the sexes".[27] At the time women's suffrage was closely linked to the temperance movement, which sought prohibition of alcohol. As a former publican and self-styled "Champion of the Common Man" Seddon initially opposed women's suffrage. In July 1893, two months after Seddon became Premier, the second of two major petitions for women's suffrage was presented to the House.[28]

This resulted in considerable debate within the Liberal Party. John Hall, a former conservative premier, moved a Bill to enact women's suffrage. Seddon's opponents within the party, led by Stout (also an advocate of temperance), managed to gather enough support for the Bill to be passed despite Seddon's opposition. When Seddon realised that the passage of the bill was inevitable, he changed his position, claiming to accept the people's will. In actuality, however, he took strong measures to ensure that the Legislative Council would vote down the Bill, as it had done previously. Seddon's tactics in lobbying the council were seen by many as underhand, and two Councillors, despite opposing suffrage, voted in favour of the bill in protest. The Bill was granted Royal Assent in September.

Nonetheless, at the 1893 general election in November, Seddon's Liberal Party managed to increase its majority.

Alcohol licensing

The debate on women's suffrage exposed deep divisions within the Liberal Party between more doctrinaire liberals, broadly led by Stout, and "popular" liberals, led by Seddon. This division was again highlighted by the debate over alcohol licensing. Seddon moved the radical Alcoholic Liquors Sale Control Bill in 1893[29] to introduce licensing districts where a majority could vote for continuance (continued liquor licensing in that district) or reduction of licences or no liquor licences at all. Votes were to be taken every three years at general elections and licensing districts were matched to electoral districts.

Old-age pensions

One of the policies for which Seddon is most remembered is his Old-age Pensions Act of 1898, which established the basis of the welfare state later expanded by Michael Joseph Savage and the Labour Party. Seddon put considerable weight behind the scheme, despite considerable opposition from many quarters. Its successful passage is often seen as a testament to Seddon's political power and influence.

Foreign policy

In the sphere of foreign policy, Seddon was a notable supporter of the British Empire. After he attended the Colonial Conference in London in 1897, he became known "as one of the pillars of British imperialism", and he was a strong supporter of the Second Boer War and sponsored preferential tariffs for trade with Britain. He is also noted for his support of New Zealand's own "imperial" designs – Seddon believed that New Zealand should play a major role in the Pacific Islands as a "Britain of the South". Seddon's plans focused mainly on establishing New Zealand dominion over Fiji and Samoa. However, his expansionist policies were discouraged by the Imperial Government. Only the Cook Islands came under New Zealand's control during his term in office.[30]

Immigration

Seddon was firmly opposed Chinese immigration to New Zealand, harbouring an ethnic prejudice against them stemming from his years in the goldfields.[31]

Although Chinese immigrants were invited to New Zealand by the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce, prejudice against them quickly led to calls for restrictions on immigration. Following the example of anti-Chinese poll taxes enacted by California in 1852 and by Australian states in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, John Hall's government passed the Chinese Immigration Act 1881. This imposed a £10 tax per Chinese person entering New Zealand, and permitted only one Chinese immigrant for every 10 tons of cargo. Richard Seddon's government increased the tax to £100 per head in 1896 ($20,990 in modern New Zealand dollars), and tightened the other restriction to only one Chinese immigrant for every 200 tons of cargo.

Seddon compared Chinese people to monkeys, and so used the Yellow Peril conspiracy theory to promote racialist politics in New Zealand. In 1879, in his first political speech, Seddon said that New Zealand did not wish her shores "deluged with Asiatic Tartars. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'."[32]

Style of government

Seddon was a strong premier, and enforced his authority with great vigour. At one point, he even commented that "A president is all we require", and that Cabinet could be abolished. His opponents, both within the Liberal Party and in opposition, accused him of being an autocrat – the label "King Dick" was first applied to him at this point.

Seddon accumulated a large number of portfolios for himself, including that of Minister of Finance (from which he displaced Joseph Ward), Minister of Labour (from which he displaced William Pember Reeves), Minister of Education, Minister of Defence, Minister of Native Affairs, and Minister of Immigration.

Seddon was also accused of cronyism – his friends and allies, particularly those from the West Coast, were given various political positions, while his enemies within the Liberal Party were frequently denied important office. Many of Seddon's appointees were not qualified for the positions that they received – Seddon valued loyalty above ability. One account, possibly apocryphal, claims that he installed an ally as a senior civil servant despite the man being illiterate. He was also accused of nepotism – in 1905, it was claimed that one of his sons had received an unauthorised payment, but this claim was proved false.

Sir Carl Berendsen recalled seeing Seddon in 1906 as a Department of Education junior innocently bearing what was an unwelcome document. A replacement was needed for a small native school. The inspectors had picked out three outstanding candidates, but Seddon picked out the last on the lengthy list; he had no academic qualifications and had just been released from gaol for embezzlement. When the Premier appointed the gentlemen from gaol, Departmental officials returned the papers and called attention to his criminal record. Berendsen cowered in the corner while with a snarl Seddon grasped his pen and wrote once more in very large letters, "Appoint Mr X". Berendsen noted though that when an Editor was required for the new School Journal, Departmental officials had agreed on the best man, but the Massey Government (which had replaced the Liberal Government) was "quite shameless in devotion to the principle of the loaves and fishes ... and the Minister of the day appointed the third choice".[33]

As Minister of Native Affairs, Seddon took a generally "sympathetic" but "paternalistic" approach. As Minister of Immigration, he was well known for his hostility to Chinese immigration – the so-called "Yellow Peril" was an important part of his populist rhetoric, and he compared Chinese people to monkeys. In his first political speech in 1879 he had declared New Zealand did not wish her shores to be "deluged with Asiatic Tartars. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'."

Successive governments had also shown a lack of firmness in dealing with Māori, he said: "The colony, instead of importing Gatling guns with which to fight Maori, should wage war with locomotives" ... pushing through roads and railways and compulsorily purchasing "the land on both sides".[34]

Religion and freemasonry

Seddon became a Freemason in 1868 when he was initiated into Pacific Lodge No 1229 (under the United Grand Lodge of England) in Hokitika.[30][36] The lodge is still extant, but has since relocated to Christchurch.[37] In 1898, while premier, he was elected Grand Master of New Zealand,[38][36] and served in that role for two years.[30]

Honours

Seddon attended Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee and received her Jubilee Medal and an appointment in the Privy Council. In 1902 he attended the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra and received his Coronation Medal.[39] During the same visit, he received the Freedom of the Borough of his home-town St Helens during a visit there in July 1902,[40] and the Freedom of the City of Edinburgh and an honorary degree LL.D. from the University of Edinburgh during a visit to the city later the same month.[41] He was also presented with the Honorary Freedom of the Worshipful Company of Tallow Chandlers on 8 August 1902.[42]

He twice refused a knighthood, wanting to be seen as a man of the people.[25]

Death

Seddon remained Prime Minister for 13 years, but gradually, calls for him to retire became more frequent. Various attempts to replace him with Joseph Ward met with failure.

In June 1906, while returning from a trip to Australia on the ship Oswestry Grange, Seddon had a massive heart attack and died suddenly 12 days before his 61st birthday, on 10 June.[44] News of his death provoked numerous public gestures of grief, which included black-bordered displays in shop windows and several public monuments, including a memorial lamp post outside the St Helens Hospital in Pitt Street Auckland. Seddon was buried in Wellington's Bolton Street Memorial Park, with his grave being marked by a large monument.[45]

Joseph Ward was away in London at the time of Seddon's death. He succeeded Seddon as Prime Minister nearly two months later, on 6 August 1906.[46]

Legacy

He is considered by academics and historians to be one of New Zealand's greatest and most revered prime ministers.[47] Seddon centralised government decision-making around himself—at his peak he exercised "almost one-man, one-party rule"[25]—and, in doing so, he established the premiership as the de facto most important political office in New Zealand.

Seddon's son Thomas replaced him as MP for Westland in the by-election following his death. When Thomas met former US President Theodore Roosevelt in 1918, he expressed admiration for his late father, particularly the labour legislation his government passed.[48]

.JPG.webp)

A statue of Seddon is located outside Parliament Buildings in Wellington, and another has a prominent position in the West Coast town of Hokitika. A town in New Zealand and a suburb of Melbourne, Australia are named after him. Wellington Zoo was originally created when a young lion was presented to Prime Minister Richard Seddon by the Bostock and Wombwell Circus. Seddon created the Zoo from this single specimen and the lion was later named King Dick in the Prime Minister's honour. The stuffed body of King Dick (the lion) is displayed on the ground floor of the Museum of Wellington City & Sea. St Mary's Church in Addington, Christchurch also has a memorial bell tower to Richard Seddon.[49]

The Duke of Argyll unveiled a memorial to Seddon in St Paul's Cathedral, London, in 1910.[50] It shows a portrait of Seddon with the inscription " To the memory of Richard John Seddon prime minister of New Zealand 1893–1906 imperialist statesman reformer born June 22nd 1845 at St Helens Lancashire buried at Observatory Hill Wellington New Zealand"

Notes and references

Notes

- Hare, Mclintock (1966). "Prime Minister: The Title "Premier"". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- "RICHARD SEDDON". Wellington Times. No. 1784. New South Wales, Australia. 11 June 1906. p. 2. Retrieved 2 April 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- Hamer 2014, p. 1.

- "Robert Stout | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- David, Hamer (1988). The New Zealand Liberals: The Years of Power, 1891–1912. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press. pp. 224–233. ISBN 1-86940-0143.

- Brooking 2014, p. 11.

- Brooking 2014, p. 17.

- Brooking 2014, p. 51.

- Brooking 2014, pp. 22–25.

- Brooking 2014, p. 13.

- Brooking 2014, p. 54.

- Brooking 2014, p. 2.

- "Cunliffe's great-uncle Dick". Grey Star. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Brooking 2014, p. 39.

- Brooking 2014, p. 42–44.

- Brooking 2014, p. 48.

- Wolfe 2005, p. 100.

- Brooking 2014, p. 44–45.

- "Declaration of the Poll". West Coast Times. No. 3219. 19 January 1876. p. 2. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Burdon 1955, p. 40.

- Hamer 2006.

- New Zealand House of Representatives (1884). Parliamentary Debates. p. 171.

- Wolfe 2005, p. 89.

- Nagel 1993.

- Gavin McLean (21 August 2014). "Richard Seddon – Biography". nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "Robert Stout". nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "Story: Ballance, John". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- "Women and the vote Page 7 – About the suffrage petition". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Hare, Mclintock (1966). "PROHIBITION – The Act of 1893". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Burdon, Randal Mathews (1966). "Seddon, Richard John". In McLintock, A.H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- "Richard Seddon | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- Burdon, Randal Mathews. King Dick: A Biography of Richard John Seddon, Whitcombe & Tombs, 1955, p.43.

- Berendsen 2009, pp. 50, 56.

- Scott 1975, chpt. 10.

- Stenhouse, John (4 April 2018). "Religion and politics". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- R.E.Pugh-Williams. "Rail and Freemasonry in New Zealand". Railway Craftsmen's Association of New Zealand. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Christchurch – Pacific Lodge of Hokitika 1229". District Grand Lodge of the South Island. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Richard Seddon, Grand Master". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- "Object: Queen Victoria Diamond Jubilee Medal, 1897". Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

- "Mr. Seddon at St Helens". The Times. No. 36813. London. 7 July 1900. p. 4.

- "The Colonial Premiers in Edinburgh". The Times. No. 36831. London. 28 July 1902. p. 4.

- "Mr Seddon at the Tallow Chandler´s Company". The Times. No. 36842. London. 9 August 1902. p. 6.

- Tom (2 July 2018). "Funeral for New Zealand's "King Dick" in 1906". Cool Old Photos. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Brooking 2014, p. 261.

- "Seddon Memorial". mch.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Bassett, Michael. "Ward, Joseph George". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- "Who was our best Prime Minister? | Jesse Mulligan, 1–4pm, 2:30 pm on 8 September 2016 | RNZ". Radio New Zealand. 8 September 2016.

- Seddon 1968, p. 299.

- "St Mary's Addington A heritage church in the heart of Addington". St Mary's Addington. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Unveiling in St. Paul's". Wanganui Chronicle. 24 March 1910. p. 3. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

References

- Berendsen, Carl (2009). Mr Ambassador: Memoirs of Sir Carl Berendsen. Wellington: Victoria University Press. ISBN 9780864735843.

- Brooking, Tom (2014). Richard Seddon: King of God's Own. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 9780143569671.

- Burdon, Randal Mathews (1955). King Dick: A Biography of Richard John Seddon. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Hamer, David A. (1988). The New Zealand Liberals: The Years of Power, 1891–1912. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 1-86940-014-3. OCLC 18420103.

- Hamer, David A. (2006). "Seddon, Richard John (1845–1906)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Christchurch: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36002. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hamer, David A. (2014). Seddon, Richard John (1845–1906). Wellington: Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Lipson, Leslie (2011) [1948]. The Politics of Equality: New Zealand's Adventures in Democracy. Wellington: Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0-86473-646-8.

- Nagel, Jack H. (1993). "Populism, Heresthetics and Political Stability: Richard Seddon and the Art of Majority Rule". British Journal of Political Science. Christchurch. 23 (2): 139–174. doi:10.1017/S0007123400009716. ISSN 0007-1234. JSTOR 194246. S2CID 154806794.

- Seddon, Thomas (1968). The Seddons, An Autobiography. Auckland, London: Collins.

- Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Heinemann.

- Wolfe, Richard (2005). Battlers Bluffers and Bully-boys: How New Zealand's Prime Ministers Have Shaped Our Nation. Random House, New Zealand. ISBN 1-86941-715-1.

Further reading

- Drummond, James Mackay (1907). . Whitcombe and Tombs Limited – via Wikisource.

External links

- Sketch of Richard Seddon asleep in Parliament during an all-night sitting, 1898

- The Seddon-Stout struggle

- "Cartoons of Dick Seddon's Royal Progress". Observer. 24 July 1897 – via Papers Past.