Richard Parmater Pettipiece

Richard Parmater (Parm) Pettipiece (1875 – 10 January 1960) was a Canadian socialist and publisher. He was one of the founders of Socialist Party of Canada, and one of the leaders of the Canadian socialist movement in British Columbia in the early 20th century. Later he moved into the moderate trade union movement, and for many years was a Vancouver alderman.

Richard Parmater Pettipiece | |

|---|---|

Alderman R.P. Pettipiece c. 1937 | |

| Born | 1875 |

| Died | 10 January 1960 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Occupation(s) | Socialist, publisher |

Early years

Richard Parmeter Pettipiece was born in Ontario in 1875. He was a newspaper vendor in Calgary as a boy, then joined the printing trade in 1890. In 1894 he moved to South Edmonton (later renamed Strathcona), now a part of Edmonton and started a weekly newspaper, the South Edmonton News.[1] Not even 20 years old, he was nicknamed "the boy editor."

His newspaper favoured freer trade with the U.S. Its editorial stance was "an advocate of radical tariff reform while in general principle it will be independent."[2]

The first ice hockey match between the newly formed South Edmonton Shamrocks and the Edmonton Thistles was held on 31 January 1896. Pettipiece was secretary of the Shamrocks, which he supported in his paper.[3] He was also active in the local branch of the Orange Order.[4]

He left South Edmonton in 1896 to found a weekly paper in Revelstoke, British Columbia, but soon sold it.[5]

Pettipiece began to publish the Lardeau Eagle in Ferguson, British Columbia, a miner's journal that published the views of the Canadian Socialist League (CSL).[6][7] In 1900 Pettipiece supported female enfranchisement in the Lardeau Eagle.[8] A strike began in Rossland, British Columbia in July 1901 in response to efforts by the mining companies to break the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) locals.[9] The companies ignored the Alien Labor Law and brought strike-breakers from the United States in large numbers. When the WFM called on the federal government to take action the prime minister Wilfrid Laurier and the justice minister David Mills replied that they did not have jurisdiction. Pettipiece said "the Laurier government is afraid to enforce the provisions of a law placed in the statutes by themselves." The strike had collapsed by November.[10]

In 1901 Pettipiece settled in Vancouver, where he joined the Vancouver Province.[1] In 1902 Pettipiece sold the Lardeau Eagle and bought an interest in Toronto-based CSL organ Citizen and Country, which he moved to Vancouver. With the help of the founder George Weston Wrigley the paper began to appear in July 1902 as the Canadian Socialist.[6]

Starting in July 1902 the Citizen and Country began appearing in Vancouver as the Canadian Socialist. The Canadian Socialist was aligned with the Canadian Socialist League. In October 1902 Pettipiece renamed the paper the Western Socialist.

After the failure of the Rossland strike, a WFM convention was held in Kamloops early in 1902, where socialism was declared the official ideology of the union. Eugene V. Debs launched a successful campaign to destroy the Progressive party and ensure socialist control of the union. In January 1903 Pettipiece was able to write that "in the Kootenays a miners' union meeting is converted into a socialist meeting without turning out the lights."[11]

In January 1903 the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) began a campaign to break the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE) local in its freight department in Vancouver, and in late February 1903 the union went on strike, with support from socialist and unions across western Canada.[12] The CPR fought the strike ruthlessly, bringing in strikebreakers from central Canada and the USA, and using spies and special police. The CPR bribed Harold Poore, the UBRE organizer in Canada, to give them union secrets. Special police fatally shot the labor and socialist leader Frank Rogers while he was picketing. Pettipiece wrote, "nowhere else in the British Empire would such a condition be possible, and it has seldom been equaled anywhere in the long and painful history of the tragedy of labor." The courts exonerated the company of responsibility.[13]

Pettipiece renamed his paper to Western Socialist, which then was merged with two other newspapers and appeared on 8 May 1903 as the Western Clarion.[6] The paper was named after the Clarion published by Robert Blatchford in England.[14] The Western Clarion had a guaranteed circulation of 6,000 three days a week. Although privately owned the paper expressed the views of the Socialist Party of British Columbia, but gave coverage to controversies among Canadian socialist groups.[15]

The morale of socialists in British Columbia was boosted by their strong showing in the 1903 provincial election.[16] The party considered that movements in Britain and the United States were not revolutionary enough. The highly developed capitalism in BC had resulted in the most advanced socialist movement in North America. Pettipiece said, "fate has decreed this position in the world's history to us, and we should prove to the workers of the world that we can rise to the occasion; let us stand firm; keep our organization iron-clad, aye "narrow" and see that we shy clear of the rocks of danger which have wrecked so many well-meaning movements."[17]

Socialist leader

In February 1905 Pettipiece attended the first meeting of the Dominion Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of Canada, chaired by John Edward Dubberley, and was named an officer and organizer of the new party.[18] The Western Clarion became the organ of the Socialist Party of Canada. Pettipiece was a committed Marxist, and the paper reflected his views. He was responsible for forming locals of the Western Federation of Miners in British Columbia, and organizing the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada.[14] By 1909 Pettipiece was almost justified in his statement that "British Columbia belongs to the Socialists."[19] He said of the SPC electoral record that "this is a showing that at least cannot be duplicated upon this western continent, if it can anywhere else in the world." The SPC saw itself as the preeminent socialist party in the world. McKenzie said, only partly in jest, "since Marx died nobody was capable of throwing light on [economic] matters except the editor of the Clarion, whoever we may happen to be."[20] Pettipiece ran as SPC candidate for Vancouver City in the provincial elections of February 1907 and November 1909, but was not elected. He ran again as SPC candidate for Ymir in the March 1912 provincial election, and again was defeated.[21]

Early in 1910 there was a revolt by the moderate and eastern European SPC members in the Prairie provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba. They founded the Social Democratic Party in July that year. The revolt spread to Alberta and British Columbia. Pettipiece was among the trade union socialists who lost faith in the ability of the SPC to lead the working class and left the party at this time.[22] Pettipiece served more than once as president of the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council (VTLC), and as its first permanent secretary. He edited the council's newspaper The Trade Unionist, which combined support for trade unionism with SPC propaganda.[19] Pettipiece edited the British Columbia Federationist (1912–20).[1] This was the organ of the BC labor federation.[23] He gave Helena Gutteridge a weekly page on woman's suffrage in the paper.[24]

During the winter of 1911–12 the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) held a number of street meetings to protest against rising unemployment. James Finlay was elected mayor on a law and order platform, and in January 1912 passed a by-law that banned outdoor meetings. Four men were arrested at a 20 January 1912 meeting organized by the IWW.[25] On 28 January 1912 R.P. Pettipiece spoke to a crowd at Vancouver's O. Powell Street Grounds.[26] He told several thousand people that he had failed to get unemployment relief from the provincial government.[27] Mounted police broke up the meeting.[26] Pettipiece was arrested and all public meetings were banned. In response, the IWW and the Socialist Party launched a committee to fight for free speech.[28] However, within a few days the B.C. Federationist called for an end to street meetings. The trade unions wanted equal treatment under the law, not free speech. The IWW was organizing street meetings to attract unskilled workers and migrants, but the trades unions did not want these people as members.[25]

World War I

Pettipiece wrote against Canadian participation in World War I (1914–18) in the B.C. Federationist. He called the war a "miserable muddle" caused by "certain kings, princes, politicians, financiers and other international scoundrels."[23] In 1915 Pettipiece wrote that the May Day festival would have to be postponed because "the workers are all too busy killing each other."[29] Officially the BC Federation of Labor supported women's suffrage, but doubts began to emerge as women replaced men in industrial jobs.[24] On 14 April 1916 the British Columbia Federationist published an editorial that Pettipiece must have approved and may have written, saying,

The noisy advocates of "votes for women" may rest assured that their pet hobby will go through with flying colors as soon as the war is ended. Industrially emancipated women must needs be armed with political power in order to withstand such assaults as might be directed against her by those masculine workers who might feel sore with her for having invaded those industrial precincts previously held sacred to themselves. The master class will see that she gets the franchise. There is little doubt of that, and with her franchise she will be a bulwark of defense to everything that is conservative in political and industrial life...[24]

The British Columbia Federation of Labor decided in January 1918 to form the Federated Labor Party (FLP) as "a united working class political party ... calculated to enlist the interest and activity of every advanced and progressive thinker." The new party's early leaders included prominent socialists such as Pettipiece, E. T. Kingsley and James Hurst Hawthornthwaite. Pettipiece made the anti-capitalist position of the party clear in a speech in March 1918 when he said, "All shades of opinion are to be represented from the social uplift element to the red-hot revolutionary. The policy of the party hinges upon the property question. The party stands for the collective ownership of the property which is collectively used, and is unalterably opposed to capitalist ownership and control of all such property."[30] However, immediately after the FLP had been founded there was a general swing among BC socialists towards industrial syndicalism and One Big Union (OBU). The BC Federation of Labor and the Vancouver Trades and Labor Council was soon aligned with this industrial action platform.[30]

Postwar career

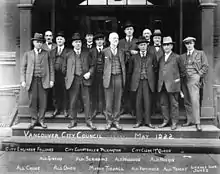

He served on Vancouver city council 1922-23, 1933-1935, and in 1936, as well as running for a federal seat.

In 1921 Pettipiece ran in the federal election on a Labour ticket in the New Westminster riding. He won 25% of the citywide vote, and captured seven city polls. He said "we had no money, little organization, and only evening work of volunteers. Despite this handicap we rolled up a vote which cannot be ignored and will be increased."[31]

Pettipiece was a member of the Vancouver city council in 1922 when the city was using proportional representation.[32] He ran for mayor in 1923 but was unsuccessful as the left vote was split over two candidates and transferable votes were no longer in use.[33]

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was founded in 1932. Pettipiece represented the CCF in council.[34] From 1933 Pettipiece pushed for abolition of the ward system of election in Vancouver, which did not give fair representation to working class areas.[35] In 1935 Pettipiece was disqualified from being candidate for aldermanic seat and two city officials lost their positions due to this.[36] In December 1936 Pettipiece and A.M. Anderson were elected to the council for the CCF, although for technical reasons Anderson could not take his seat.[37] After Pettipiece questioned CCF policy, the party refused to endorse him in the December 1937 civic elections.[34] Pettipiece ran on the Non-Partisan Association (NPA) platform, and failed to be elected.[38]

Pettipiece was a director of Vancouver General Hospital for 27 years. He was president of the International Typographical Union, founded in 1897, for four terms.[5] Richard Parmater Pettipiece died in 1960, aged about 85.[1]

Views on race

Pettipiece's position on racial matters was ambivalent. In March 1908 he wrote in The Trades Unionist that "In the fastest growing Oriental section of the city every conceivable sort of the rankest kind of "sweat shops" exist; or perhaps thrive would be a better term. And as sort of a refuge for the social garbage as a result of such economic conditions, the Chinese have provided the town with plenty of opium joints, where over 100 white women, social outcasts who have fallen to the last depths of degradation, are imprisoned victims of these monstrous dens of iniquity."[39]

In 1913 Pettipiece was asked about Asiatic immigration in an interview. He said he had no objection, "We aim to unite the laborers of all nations in one solid army against capital ... Let them come in, we say! They will make so many more votes to overthrow capital! It isn't labor that opposes the Oriental. No—you bet! Let 'em come in!" Pressed further, he equivocated, "As a father, I don't want the Hindu in here any more than you do as a woman. Let the Asiatics have separate schools. As a citizen, I do not want the Asiatic. ... You can't assimilate him to our civilization ... [but] labor has found that we might better have the cheap Asiatics come in here and organized into our fighting ranks, than have the cheap products of Asiatic labor come in here and undersell our labor products."[40]

References

- Richard Parmeter Pettipiece, World Socialist Movement.

- Monto, Old Strathcona (2012)

- Historical Society of Alberta 2001.

- Tom Monto. Old Strathcona Edmonton`s Southside Roots. Crang Publishing, Alhambra Books (2012)

- Brissenden & Loyie 2014.

- Milne 1973, p. 1.

- McCormack 1991, p. 24.

- American Journalism 1997, p. 456.

- McCormack 1991, p. 38.

- McCormack 1991, p. 39.

- McCormack 1991, p. 41.

- McCormack 1991, p. 45.

- McCormack 1991, p. 46.

- Hardt & Brennen 1995, p. 187.

- Milne 1973, p. 2.

- McCormack 1991, p. 32.

- McCormack 1991, p. 33.

- Milne 1973, p. 10-11.

- McCormack 1991, p. 62.

- McCormack 1991, p. 70.

- Richard Parmater Pettipiece, Canadian Elections Database.

- McCormack 1991, p. 74.

- McCormack 1991, p. 119.

- Howard 2011, p. 67.

- Leier 1989, p. 48.

- Davis 2014.

- Bitter & Weber 2011.

- O. Powell Street Grounds ... CommunityWalk.

- McCormack 1991, p. 120.

- Mills 1991, p. 72.

- Warburton & Coburn 2011, p. 130-131.

- Edmonton Bulletin, December 13, 1923

- Smith 1982, p. 51.

- Smith 1982, p. 58.

- Smith 1982, p. 54.

- Smith 1982, p. 52.

- Howard 2011, p. 188.

- Howard 2011, p. 190.

- Spencer 2005, p. 28.

- Chang 2012, p. 145.

Sources

- American Journalism: The Publication of the American Journalism Historians Association. The Association. 1997.

- Bitter, Sabine; Weber, Helmut (2011). "January". A Sign for the City. City of Vancouver Public Art Program. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Brissenden, Constance; Loyie, Larry (2014). "Parm (Richard Parmater) Pettipiece". HALL OF FAME. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Chang, Kornel S. (2012). Pacific Connections: The Making of the U.S.-Canadian Borderlands. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27168-5. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Davis, Chuck (2014). "Chronology 1912". The History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Hardt, Hanno; Brennen, Bonnie (1995). Newsworkers: Toward a History of the Rank and File. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-2706-6. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Historical Society of Alberta (2001). "'Puck-eaters': hockey as a unifying community experience in Edmonton and Strathcoma, 1894-1905." The Free Library. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Howard, Irene (2011-11-01). The Struggle for Social Justice in British Columbia: Helena Gutteridge, the Unknown Reformer. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-4287-7. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Leier, Mark (Spring 1989). "Solidarity on Occasion: The Vancouver Free Speech Fights of 1909 and 1912". Labour/Le Travail. 23: 39–66. doi:10.2307/25143135. JSTOR 25143135. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- McCormack, A. Ross (1991). Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement 1899-1919. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-7682-3. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Mills, Allen George (1991-01-01). Fool for Christ: The Political Thought of J.S. Woodsworth. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6842-2. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Milne, J. M. (1973). "History of the Socialist Party of Canada" (PDF). World Socialist Movement. Retrieved 2014-08-30.

- "O. Powell Street Grounds/ Oppenheimer Park". CommunityWalk. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- "Richard Parmater Pettipiece". Canadian Elections Database. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- "Richard Parmeter Pettipiece". World Socialist Movement. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Smith, André A.B. (1982). "The CCF, NPA, and Civic Change: Provincial Forces Behind Vancouver Politics 1930-1940". BC Studies (53). Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Spencer, David R. (2005). "Race and Revolution Canada's Victorian Labour Press and the Chinese Immigration Question". The Public. 12 (1). Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- Warburton, Rennie; Coburn, David (2011-11-01). Workers, Capital, and the State in British Columbia: Selected Papers. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-4317-1. Retrieved 2014-09-10.