Richard Simpson (martyr)

Richard Simpson (or Sympson) (c. 1553 – 24 July 1588) was an English priest, martyred in the reign of Elizabeth I. He was born in Well, in Yorkshire. Little is known of his early life, but according to Challoner's Memoirs of Missionary Priests, he became an Anglican priest, but later converted to Catholicism.[1] He was imprisoned in York as a Catholic recusant; on being released, he went to Douai College, where he was admitted on 19 May 1577.[1] The date of his ordination is unknown; the college, at this time, was preparing for its move to Rheims, and record keeping was affected.[2] But it is known that the ordination took place in Brussels within four months of his admission to the seminary, and that on 17 September, Simpson set out for England to work as a missionary priest. He carried out his ministry in Lancashire and Derbyshire.

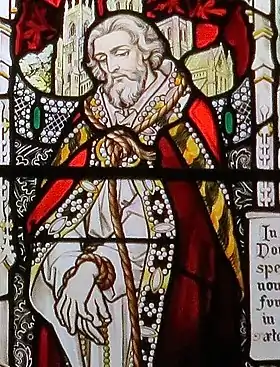

Blessed Richard Simpson | |

|---|---|

Stained glass window in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church in Bridge Gate, Derby. | |

| Priest and Martyr | |

| Born | c. 1553 Well in Yorkshire |

| Died | 24 July 1588 (aged 34 - 35) St Mary's Bridge in Derby |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 22 November 1987 by John Paul II |

| Feast | 24 July and 22 November |

| Attributes | bound hands, noose in neck |

According to Challoner, Simpson was arrested and banished in 1585, but returned quickly to England.[1] While travelling in the Peak District, in January 1588, he met a stranger who pretended so successfully to be a Catholic, that Simpson revealed his priesthood. The man denounced him at the next town, and he was arrested.[3] He was imprisoned in Derby, and was condemned to death for treason at the Lenten Assizes. However, he was reprieved until the Summer Assizes.

Traditional accounts of Simpson's life state that the stay of execution was granted because he had given some indication that he would conform and attend an Anglican service, or hear a sermon.[1] There is no record that he actually did so. According to Connelly, his surrender was not complete, and did not satisfy the judge, since he was not released but merely remanded for a second trial.[4] Sweeney offers an alternative explanation for his reprieve.[3] He points out that the execution of priests stopped for ten months in September 1587, the last one being that of George Douglas at York on 9 September. They were resumed ten months later, with the execution of Richard Simpson and his companions. Sweeney suggests that Elizabeth and her government, on hearing news of the preparations that Philip of Spain was making for his enterprise, may have decided to halt the persecution of Catholics to remove one of his complaints. By July 1588, the Armada was on its way, and there was no longer any motive for sparing priests. Simpson and his companions were the first of thirty-two priests martyred that year.

In Derby Gaol, before his second trial, Richard Simpson met with two other priests, Nicholas Garlick and Robert Ludlam. Traditional accounts indicate that they brought the wavering priest back to the Catholic faith. Whether his reprieve was because of an agreement to attend a Protestant service or because of a temporary ban on executing priests, it is certain that at his second trial, on 23 July, Simpson firmly declared himself a Catholic and was condemned to death with his two companions. The sentence was to be carried out the next day, at St Mary's Bridge, in Derbyshire.

Henry Garnet, cited in Sweeney, recounts that the priests spent their last night in the same cell as a woman condemned to death for murder, and that in the course of the night, they reconciled her to the Catholic faith, and she was hanged with them the next day.[5]

On 24 July 1588, the three priests were drawn on hurdles to the place of execution, where they were hanged, drawn, and quartered. Simpson was apparently to have been executed first, but reports state that Garlick hastened to the ladder before him and kissed it, going up first, either because, as suggested by Anthony Champney,[6] Simpson was showing some signs of fear, or, as suggested by Challoner,[7] Garlick suspected that there was a danger that his companion's courage might fail him. Simpson was next to die, and an eyewitness, quoted in Challoner, said that he "suffered with great constancy, though not with such (remarkable) signs of joy and alacrity as the other two."[1] When his body was cut down for quartering, he was found to be wearing a hairshirt. Another eyewitness, quoted in Hayward,[8] says:

What he said to his executioner I cannot hear, but embracing the ladder he kissed the steps. When he was in quartering, the people cried out, 'A devil, a devil', because he had on him a shirt of hair; but the wiser sort said he wore it because he had fallen.

A poem by an anonymous writer, who seems to have been present at the executions, and is quoted in Challoner,[1] describes the executions as follows:

When Garlick did the ladder kiss,

And Sympson after hie,

Methought that there St. Andrew was

Desirous for to die.

When Ludlam lookèd smilingly,

And joyful did remain,

It seemed St. Stephen was standing by,

For to be stoned again.

And what if Sympson seemed to yield,

For doubt and dread to die;

He rose again, and won the field

And died most constantly.

His watching, fasting, shirt of hair;

His speech, his death, and all,

Do record give, do witness bear,

He wailed his former fall.

Richard Simpson and his two companions were declared venerable in 1888, and were among the eighty-five martyrs of England and Wales beatified by Pope John Paul II on 22 November 1987.

See also

References

- Challoner, Richard. Memoirs of Missionary Priests, [1741]. New edition revised by John Hungerford Pollen. London. Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1924, p. 132.

- Connelly, Roland. The Eighty-five Martyrs. Essex. McCrimmons Publishing Company, 1987, p. 38.

- Sweeney, Garrett. A Pilgrim's Guide to Padley. Diocese of Nottingham, 1978, p. 9.

- Connelly, p. 39.

- Sweeney, p. 10

- Anthony Champney. History of the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, quoted in Challoner, p. 131.

- Challoner, p. 131.

- Hayward, F.M. Padley Chapel and Padley Martyrs. Derby. Bemrose and Sons, 1903. 2nd edition 1905, p. 35.