Risdon Cove

Risdon Cove is a cove located on the east bank of the Derwent River, approximately 7 kilometres (4 mi) north of Hobart, Tasmania. It was the site of the first British settlement in Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, the island state of Australia. The cove was named by John Hayes,[1] who mapped the river in the ship Duke of Clarence in 1794, after his second officer William Bellamy Risdon.

In 1803 Lieutenant John Bowen was sent to establish a settlement in Van Diemen's Land. On the advice of the explorer George Bass he had chosen Risdon Cove. While the site was a good one from a defensive point of view, the soil was poor and water scarce. Lady Nelson anchored at Risdon on the eastern shore of the Derwent River on Wednesday 8 September 1803, five days before the whaler Albion arrived with Lt. Bowen on board. The 49 people aboard the Lady Nelson and Albion made a curious party of soldiers, sailors, settlers and convicts.

In 1804 Lieutenant Colonel David Collins arrived in the Derwent from Port Phillip on Ocean. Within a few days he rejected Risdon Cove as a suitable settlement site, for its inadequate source of fresh water, and moved his party across the river to Sullivans Cove. The military and convicts disembarked from Ocean near Hunter Island on 20–21 February 1804 and thus beginning what is now Hobart. Lady Nelson landed the free settlers at New Town Bay on 22 February.

One of the first land grants at Risdon Cove was made to Dr William F A I'Anson, the chief surgeon who arrived with Lieutenant-Governor Collins in 1804.[2]

3 May 1804

The original records show that a large group of Aboriginals walked into the fledgling settlement. The settlement's guards mistakenly thought they were under attack and killed some of the intruders.

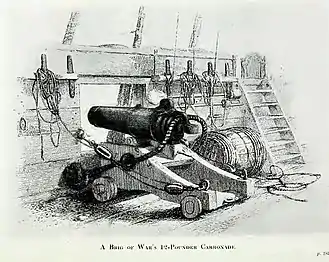

About 300 aboriginals, men, women and children, who had banded together approached the Risdon Cove settlement whilst occupied on a kangaroo hunt. The Aboriginal people had arrived at the settlement and some were justifiably upset by the presence of the colonists. There had been no widespread aggression, but if their displeasure spread and escalated, Lt. Moore, the commanding officer at the time, and his dozen or so soldiers, could not be expected to be able to protect the settlement from a mob of such size. The soldiers were therefore ordered to fire a 12-pounder carronade (a short-barrel, heavy calibre naval cannon known to sailors as "the smasher") in an attempt to disperse the aboriginals. Reverend Robert Knopwood heard "roar of the cannon at Risdon at 2 p.m". That being said, at least a second shot would be necessary to adjust the elevation and windage. The 12-pounder carronade was one of two ordered to be salvaged from the ship Investigator, by Governor King and given to Lieutenant Bowen, "unmounted". The 12-pounder carronade weighed 330kg 728 pounds. A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century. It was probably a blank round, although some historians allege grape shot was used to explain an alleged but uncorroborated high figure of deaths.

In addition, two soldiers fired Brown Bess muskets in protection of a Risdon Cove settler being beaten on his farm by aboriginals carrying waddies (clubs). Bear in mind a well disciplined and trained soldier could reload and fire the flintlock musket once every 20 seconds. The Brown Bess musket is a muzzle-loading, smooth bore, 990mm long barrel, flintlock, weighing about 5kg, shooting a 0.75 calibre projectile. Better used as a club. It was that inaccurate. Its effective firing range is 100 to 300 metres. Infantrymen did not aim their muskets but more or less pointed them in the direction of the enemy. The Brown Bess did not have sights, like modern rifles or shotguns. The affray began at 11:00 in the morning and the final shot, the carronade was heard in Hobart 3 hours later. That is 10,800 seconds. The Rate of Fire is 20 seconds so there were 540 reloads and shots fired, if a soldier's powder was dry and there were no misfires. When you multiply that by the number of soldiers armed with the Brown Bess musket and there would be thousands of musket balls, but the only musket balls found were slag, in a fireplace, along with a musketball probably to emit heat on cold damp nights.

In the 1814 "To All Sportsmen", Colonel George Hanger wrote, "A soldier's musket, if not exceedingly ill-bored (as many are), will strike a figure of a man at 80 yards; it may even at a hundred; but a soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded by a common musket at 150 yards, providing his antagonist aims at him; and as to firing at a man at 200 yards with a common musket, you may as well fire at the moon and have the same hope of hitting him. I do maintain and will prove that no man was ever killed at 200 yards, by a common musket, by the person who aimed at him."

These soldiers killed one aboriginal outright, and mortally wounded another, who was later found dead in a valley. Moore's account lists three killed and some wounded. It is therefore known that in the conflict some aboriginals were killed, and that the colonists "had reason to Suppose more were wounded, as one was seen to be taken away bleeding".[3] It is also known that an infant boy about 2–3 years old was left behind in what was viewed as a "retreat from a hostile attempt made upon the borders of the settlement".[4]

"There were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded" according to the Edward White, an Irish convict who later spoke before a committee of inquiry nearly 30 years later in 1830, but could not give exact figures.[5] White alleged to have been an eyewitness, although he was working in a creek bed where the escarpment prevented him from viewing events. Claiming to be the first to see the approaching aboriginals, he also said that "the natives did not threaten me; I was not afraid of them; (they) did not attack the soldiers; they would not have molested them; they had no spears with them; only waddies".[5] That they had no spears with them is questionable, and his claims need to be assessed with caution.

In a recently released book, titled, "TRUTH-TELLING AT RISDON COVE" ISBN 978-0-646-85716-9 documented evidence has been presented proving that the Edward White who gave eye-witness testimony before the 16 March 1830 Broughton Committee, was not actually there. The only possible Edward White, who boarded the Atlas 1 in Cork, 29 November 1801, did not arrive at Port Jackson 7 July 1802.

Consider this. Historical records cite the following, "Atlas's 222-day voyage was one of the worst in the history of transportation to Australia. During the voyage 64 people died; another four dying shortly after disembarkation. The remainder were "in a dreadfully emaciated and dying state" (Governor King). Governor King asked a committee of enquiry whether Captain Brooks' private trade goods which took up space in the hospital and prison and the unnecessary stops en route to Australia contributed to the deaths. The committee stated that mortality had been caused by "the want of proper attention to cleanliness, the want of free circulation of air, and the lumbered state of the prison and hospital"."

The other Edward Whites transported to the colony were:

- Edward White, one of 175 convicts transported on the Morley, November (1816)

- Edward White, one of 10 convicts transported on the Seppings, (01 December 1839)

- Edward White, one of 230 convicts transported on the Elphinstone, (06 April 1842), who arrived in Van Diemen's Land

- Edward White, one of 389 convicts transported on the Moffatt, (10 August 1842), who arrived in Van Diemen's Land

- Edward White, one of 204 convicts transported on the Bangalore, (28 March 1848), who arrived in Van Diemen's Land

- Edward White, one of 300 convicts transported on the Randolph, (24 April 1849)

- Edward White transported on the London, (December 1850)

- Edward White, one of 270 convicts transported on the Lord Raglan, (03 March 1858)

- Edward White, one of 210 convicts transported on the Adelaide, (13 May 1863)It should be obvious, that none of the other nine Edward Whites could have been at Risdon Cove, 3 May 1804.

His contemporaries had believed the approach to be a potential attack by a group of aboriginals that greatly outnumbered the colonists in the area, and spoke of "an attack the natives made", their "hostile Appearance", and "that their design was to attack us".[3]

A macabre postscript to the story was an allegation that the bones of some of the Aboriginal people were shipped to Sydney in two casks.[5] There is no documentary evidence of this or of a massacre.

20th century

The site at Risdon Cove was farmed until 1946. By the 150th anniversary celebrations (September 1954) land had been acquired by the State Government to add to the reserve.[6] Angela McGowan excavated the site in 1978-80.[7]

The hand-over of the Risdon Cove site, which includes the Bowen Memorial, was part of the Aboriginal Lands Act 1995. The transfer occurred on 11 December 1995, and since then Aboriginal Tasmanians have maintained and developed the site as a cultural and an educational facility.[6]

References

- Roe, Margriet (1966). "Hayes, Sir John (1768–1831)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- "Prestige Philately and Mossgreen". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Refshauge, W.F. (June 2007). "An analytical approach to the events at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society.

- "NATIVES". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803–1842). NSW: National Library of Australia. 2 September 1804. p. 2. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Tardif, Phillip (6 April 2003). "So who's fabricating the history of Aborigines?". Melbourne: The Age.

- Risdon Cove History. Members.iinet.net.au. Retrieved on 2013-09-27.

- McGowan, Angela (1985). Archaeological Investigations at Risdon Cove Historic Site: 1978-1980. Sandy Bay, Tasmania: Tasmania National Parks and Wildlife Service.