Roar (film)

Roar is a 1981 American adventure comedy film[3][4] written and directed by Noel Marshall, and produced by Marshall and Tippi Hedren. Roar's story follows Hank, a naturalist who lives on a nature preserve in Africa with lions, tigers, and other big cats. When his family visits him, they are instead confronted by the group of animals. The film stars Marshall as Hank, his real-life wife Tippi Hedren as his wife Madeleine, with Hedren's daughter Melanie Griffith and Marshall's sons John and Jerry Marshall in supporting roles.

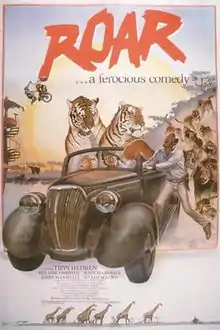

| Roar | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Noel Marshall |

| Written by | Noel Marshall |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Jan de Bont |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Terence P. Minogue |

Production company | Film Consortium[1] |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $17 million |

| Box office |

|

In 1969, while Hedren was filming Satan's Harvest in Mozambique, she and Marshall had occasion to observe a pride of lions move into a recently vacated house, driven by increased poaching. They decided to make a film centered around that theme, with production starting when the first script was completed in 1970. They began bringing rescued big cats into their homes in California and living with them. Filming began in 1976; it was finished after five years. The film was fully completed after 11 years in production.

Roar was not initially released in North America. Instead, in 1981, Noel and John Marshall released it internationally. It was also acquired by Filmways Pictures and Alpha Films. Despite performing well in Germany and Japan, Roar was a box office failure, grossing $2 million worldwide against a $17 million budget. In 2015, 34 years after the film's original release, it was released in theaters in the United States by Drafthouse Films. Roar's message of protection for African wildlife as well as its animal interactions were praised by critics, but its plot, story, inconsistent tone, dialogue, and editing were criticized.

The cast and crew members of Roar faced dangerous situations during filming; seventy people, including the film's stars, were injured as a result of multiple animal attacks. Flooding from a dam destroyed much of the set and equipment during its production, and the film's budget increased drastically. In 1983, Hedren founded the Roar Foundation and established the Shambala Preserve sanctuary, to house the animals appearing in the film. She also wrote a book, The Cats of Shambala (1985), about the events that took place during its production. The film has been described as "the most dangerous film ever made" and "the most expensive home movie ever made", and has gained a cult following.

Plot

American naturalist Hank (Noel Marshall) lives on a nature preserve in Tanzania with a collection of big cats to study their behavior. Although he is due to pick up his wife Madeleine (Tippi Hedren) and their children John, Jerry, and Melanie (Melanie Griffith) from the airport to bring them to his home, he is delayed by his friend Mativo (Kyalo Mativo) warning him that a committee is coming to review his grant. As he shows Mativo around his ranch and the rest of the preserve while they wait, Hank explains the nature of the lion pride and their fear of Togar, a rogue lion who often quarrels with the pride's leader, Robbie. Hank asks Mativo to help keep the pride safe.

The grant committee arrives. One of its members, Prentiss (Steve Miller), disapproves of the big cats and threatens to shoot them. A fight between two lions distracts Hank; he breaks it up despite having his hand bitten. While Hank is bandaging his hand, the tigers attack members of the committee and injure some of them, and, although Hank offers assistance, they leave in fear. Mativo expresses his concerns over another attack when Hank brings his family to the ranch. As they leave for the airport on Mativo's boat, two tigers jump aboard, traveling with them. Mativo steers into a log in the water, causing the craft to sink. The two men swim to safety.

Madeleine, John, Jerry, and Melanie are advised by an airport attendant, Lenord (Lenord Bokwa), to board a bus. They arrive at the ranch and enter the house, realizing that it has been left unattended. When Madeleine and Jerry open the windows and doors, they are shocked to see the lions eating a zebra carcass in front of the house. The family are frightened when animals enter the house and try to escape but Togar pursues them. Jerry finds a rifle and tries to shoot Togar while he is fighting Robbie. Melanie fears that her father has been killed by the animals.

Hank and Mativo—still pursued by the tigers—take two bikes from a local village. To prevent the tigers from following Hank to the airport, Mativo climbs a tree and distracts them. Hank encounters the airport attendant, who tells him that his family have taken the bus to his ranch. Hank drives back in Lenord's car and rescues Mativo from the tree. One of the car's tires is punctured on a rocky road, and Hank runs to the ranch while Mativo fends off the tigers with an umbrella.

The following morning, the family board Hank's boat to try to escape, but an elephant pulls the craft back to shore and destroys it. John goes for help on Hank's motorcycle, but he is chased by the big cats, and drives into the lake. After escaping another elephant, the family swims across the lake and find another house that they use to sleep in. When they awake, they find themselves surrounded by the pride and conclude that, since they are still alive, the animals do not intend to hurt them.

Prentiss tries to persuade the committee to hunt down and kill Hank's lions. Though he is unsuccessful, he and Rick (Rick Glassey), another committee member, shoot many of the big cats anyway. Eventually Togar attacks them and although Hank sees the assault and tries to intervene, the lion kills Prentiss and Rick before returning to the house to battle Robbie. Robbie stands up to Togar and the fight ends. Hank arrives at the ranch to find his family waiting for him. Mativo arrives, and Hank asks him not to mention Prentiss or Rick's death; he is introduced to Hank's family, who agree to stay for the week.

Cast

- Noel Marshall as Hank, a naturalist who lives alongside numerous animals in Africa. Despite his lack of experience with writing and acting,[5] Marshall, in addition to producing, directing, and financing the film, had lived with the big cats for years and understood their behavior. In Hedren's opinion, he had developed a relationship with the animals and displayed a much-needed confidence and bravery when handling them, making him the best and only plausible choice as Hank.[6]

- Tippi Hedren as Madeleine, Hank's wife. Hedren was a professional actress; she had played the lead character in Alfred Hitchcock's films The Birds (1963) and Marnie (1964). She had also completed a few films in Africa.[7][8]

- Melanie Griffith as Melanie, the daughter of Hank and Madeleine. Griffith had a promising career at the time, appearing in the films Night Moves, The Drowning Pool, and Smile (all made in 1975).[9] She left the film after a fight between two lions, saying that she did not want to "come out of this with half a face."[7] Although Griffith was replaced by her friend, actress Patsy Nedd, she later expressed interest in the film and reshot many scenes.[10][11]

- John Marshall as John, the eldest son of Hank and Madeleine. John Marshall (Noel Marshall's middle son) had acted in small television roles from the age of five.[12]

- Jerry Marshall as Jerry, the youngest son of Hank and Madeleine. Jerry Marshall had, like his brother, been cast in a small number of commercials but had not acted in film and television as much as John and Melanie.[13]

- Kyalo Mativo as Mativo, Hank's friend and assistant zoologist. Born in Kenya, Mativo (who died on June 7, 2021[14]) was a Kamba, and was chosen over other two men; one Senegalese and one Nigerian. He was majoring in film at UCLA, held a PhD in Developmental Journalism,[14] wrote and directed for Voice of Kenya, and had previously acted in two German short films before taking the role, under stipulation that he "only be with those animals while [we're] filming".[15][16]

Expert and experienced animal trainers such as Frank Tom, Rick Glassey and Steve Miller were given acting parts as committee members attacked by tigers.[17] Zakes Mokae plays a committee member,[18] and Will Hutchins portrays a man in a rowboat.[19] The untrained lions Robbie, his offspring Gary, and Togar are all credited as actors.[20]

Production

Development

Roar was conceived by husband and wife Noel Marshall and Tippi Hedren in 1969. Marshall was Hedren's talent agent while she starred in Satan's Harvest, which was filmed in Mozambique.[21] Near the film set, they came across an abandoned plantation house in Gorongosa National Park which had been overrun by a pride of lions, and were told by their bus guide and local residents that animal populations were becoming endangered due to poaching; this inspired them to consider making either one[22][23] or a series of films.[24]

It was an amazing thing to see: The lions were sitting in the windows, they were going in and out of the doors, they were sitting on the verandas, they were on the top of the Portuguese house, and they were in the front of the house [...] It was such a unique thing to see and we thought, for a movie, let us use the great cats as our stars.

Marshall and Hedren discussed the film with their family (Melanie Griffith, Joel, John, and Jerry Marshall), who liked the idea and agreed to participate as actors, except Joel, who preferred to be the art director and set decorator. Marshall and Hedren visited animal preserves in their free time and talked to lion experts. They learned they would have to film in the United States, as tame lions were rare in Africa.[25] A number of lion tamers warned that it was impossible to bring a large number of big cats together on a film set. Other tamers, such as animal trainer Ron Oxley—who brought a lion named Neil over to introduce the family to big cats—suggested that they obtain their own animals, give them basic training, and gradually introduce them to each other.[21][26] The Marshalls developed ideas for funding the project and estimated that the film would be completed on a budget of $3 million.[27]

Pre-production

Marshall wrote the first script for the project in the spring of 1970, and gave it the working title Lions; later, he changed it to Lions, Lions and More Lions.[28][29] He also enlisted the assistance of actor and voice artist Ted Cassidy, with whom he had co-written and produced The Harrad Experiment.[30] The original script allowed for up to thirty or forty trained lions.[21] Marshall was also inspired by Mack Sennett's slapstick routines, and decided to incorporate a mixture of comedy, drama, and moments of "stark terror" in the human and animal encounters, with an underlying message of the need for the preservation of African wildlife.[31] Scenes where animals chase after the characters required that the actors pretend to be scared and scream, in order to trigger a reaction from the animals. The script developed with frequent changes but always allowing for inclusion of spontaneous actions by the animals, such as playing with the family's boat or riding a skateboard. This led some of the lions to be credited as writers.[3][32]

Marshall and Hedren began keeping young lions that they had acquired from zoos and circuses in their house in Sherman Oaks. This was illegal as they did not secure permission from the authorities beforehand—though it was before the more stringent regulations of the Endangered Species Act of 1973.[33] The authorities discovered the animals in 1972 and ordered the family to remove them from the property.[34][8] The couple purchased land in Soledad Canyon, and hired staff to construct a set along with a two-storey house inspired by African architecture. The house was supported by fourteen telephone poles which made it sturdy enough to bear the weight of fifty big cats, or 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg).[35][36] The staff was composed of non-union workers; the Marshalls did not use union workers as they were unable to afford them and were afraid of breaking union rules.[27] A flat roof was installed on the house, the surrounding land's Californian desert characteristics were adapted to mimic Tanzania, by the planting of thousands of cottonwoods and Mozambique bushes, and a nearby creek was dammed to create a lake.[37][38] A crew of five men cordoned off areas of up to 2,000 square feet (190 m2) with 14-foot (4.3 m) fences to prevent the animals from escaping. A miniature studio was constructed alongside numerous other buildings, such as editing rooms and a kitchen commissary. An animal hospital, elephant barn, and a 10,000-pound (4,500 kg) freezer—to store meat for the big cats—were also constructed.[39] Hedren operated a backhoe on the set, and was in charge of the film's wardrobe, which she described as a plain "wash-and-wear look".[40][41]

After Marshall took in two infant Siberian tigers and an African bull elephant named Timbo from the Okanagan Game Preserve, he decided to revise the film's script to include different animals, and changed the formerly leo-centric title to Roar.[42] Another addition to the script involved Timbo crushing the family's rowboat, inspired by seeing the elephant destroy a metal camper shell.[43] The family would eventually accumulate, by 1979, 71 lions, 26 tigers, a tigon, nine black panthers, 10 cougars, two jaguars, four leopards, two elephants, six black swans, four Canada geese, four cranes, two peacocks, seven flamingos, and a marabou stork; the only animal they turned down was a hippopotamus.[38][44] Marshall and Hedren had to hire animal trainers when they received more lions; one trainer, Frank Tom, brought his pet cougar that needed re-homing.[17] After six years of production had been completed, the big cats numbered about 100; the total would eventually reach 150.[45][46]

Issues with funding started in 1973, as by then the cost of the crew and feed for the animals was $4,000 per week.[47] The family sold their four houses and 600 acres (240 ha) near Magic Mountain to pay debts, and Marshall's commercial-production company went bankrupt.[48] He had been executive producer of The Exorcist and the proceeds from that film partially funded production.[49][46] The Marshalls also sold some possessions, including Hedren's fur coat, given to her by Alfred Hitchcock for her starring role in The Birds.[50][51] The lack of funds meant that members of the family had to cover crew tasks and take on other work. John Marshall was an animal wrangler, set mechanic, boom operator, and camera operator; he also undertook veterinary work, such as giving vaccines and drawing blood from the animals.[52] In a 1977 interview, Noel Marshall was asked why he took personal risks for the project:

You get into anything slowly. We have been on this project now for five years. Everything we own, everything we have achieved, is tied up in it. Today we're 55 percent complete. We're at a point where we just have to do it.

Some of the big cats were plagued with airborne illnesses; 14 lions and tigers died as a result.[54][55]

Filming

Principal photography began on October 1, 1976, and was initially scheduled to last for six months,[56] but filming was restricted to five months at a time because the cottonwood trees on set turned brown from November until March.[57] Filming the big cats was difficult and frustrating; cinematographer Jan de Bont often spent hours setting up five cameras and waiting for the cats to do something that could be included in the film.[23] This eventually led to Marshall and the crew recording footage in documentary style with up to eight Panavision 35mm cameras.[49] One scene where Marshall and Mativo drive a 1937 Chevrolet containing two tigers took seven weeks to complete, because Glassey and Miller had to train the animals to ride in a car.[58][59] Marshall often refused to stop filming because he did not want to lose a take; sometimes only one take was usable from a day's filming.[60][52]

The opening footage of Marshall racing a bull giraffe on a motorcycle was filmed in Kenya, with the location acknowledged in the credits.[61] One session involved a leopard licking Hedren's face which had been coated in honey; Hedren considered it to be one of the most dangerous scenes she agreed to film as although handlers were 8 feet (2.4 m) away, they would not have been able to stop the cat from biting her.[62] In the scenes where some of the big cats are shot and killed by hunters, the effect was achieved by filming the animals when they were tranquilized for their annual blood draw.[11]

Filming took five years to complete.[38] Although Hedren has claimed that principal photography ended on October 16, 1979, after just over three years,[63] additional pick-up shots were filmed in Kenya during the editing stage.[64] The total production time was 11 years.[7][23]

Injuries and set damages

Due to the large number of untrained animals on set, there were a reported 48 injuries within two years of the start of filming.[65] It has been estimated that, of Roar's 140-person crew,[44] at least 70 were injured during production.[38] In a 2015 interview, John Marshall said that he believed the number of people injured was over 100.[45]

Noel Marshall was bitten through the hand when he interacted with male lions during a fight scene; doctors initially feared that he might lose his arm.[38][53] By the time he suffered eight puncture wounds on his leg caused by a lion which was curious about his anti-reflection makeup, Marshall had already been bitten around eleven times.[66] He was hospitalized when his face and chest were injured[67] and was diagnosed with blood poisoning.[38] Marshall was also diagnosed with gangrene after being attacked many times.[48] It took Marshall several years to fully recover from his injuries.[68] During a promo shoot in 1973, Hedren was bitten in the head by a lion, Cherries, whose teeth scraped against her skull. She was taken to Sherman Oaks Hospital, where her wounds were treated and she was given a tetanus shot.[69][70] She was admitted to Antelope Valley Hospital after Tembo, the five-ton elephant, picked her up by and fractured her ankle with his trunk before bucking her off his back; Hedren said that Tembo had been trying to keep her from falling and was not at fault. She was left with phlebitis and gangrene, in addition to a fractured hand and abrasions on her leg. Several days earlier Tembo had bucked his trainer into a tree and broken her shoulder.[71][72][53] Hedren was also scratched on the arm by a leopard and bitten on the chest by a cougar.[23] Griffith received 50 sutures after being attacked by a lioness. It was feared that she would lose an eye, but she eventually recovered without being disfigured, although she did require some facial reconstruction.[45][23] A lion jumped on John Marshall and bit the back of his head, inflicting a wound that required 56 sutures.[7] Jerry Marshall was bitten in the thigh by a lion while he was in a cage on set, and he was in hospital alongside Hedren for a month.[73][53]

Most members of the crew were injured, including de Bont, who was scalped by Cherries while he was filming under a tarpaulin;[74][52][75] he received 220 sutures, but resumed his duties after recovering.[48][52] Togar, one of the lead lions, bit assistant director Doron Kauper in the throat and jaw and tried to pull off one of his ears after Kauper unintentionally cued an attack; Kauper also received injuries to his scalp, chest and thigh, and he was admitted to Palmdale General Hospital where he had to undergo four and a half hours of surgery.[76][65] Although the attack was reported as nearly fatal, a nurse told a Santa Cruz Sentinel reporter that Kauper's injuries were acute (sudden and traumatic), but that he was conscious and in fair condition after the surgery.[76] After witnessing the attacks, twenty crew members left the set en masse;[38] turnover was high, and many did not want to return.[54] Because of Marshall's financial proceeds from his producer credit on The Exorcist, rumors spread that the set of Roar was plagued by the "curse of The Exorcist".[49]

Pipes and berms from Aliso Canyon became flooded with water and burst on February 9, 1978, after a night of heavy rain. Both were pointed towards the Marshall property to redirect water from the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks. The property was destroyed by a 10-foot (3.0 m) flood, from which four sound-crew members had to be rescued. Marshall, who had left the hospital despite being scheduled to undergo knee surgery, helped to rescue many of the animals.[77] Fifteen lions and tigers escaped from the set after fences and cages collapsed; the sheriff and local law enforcement killed three lions, including Robbie the lead lion,[60][38] who was replaced with another lion, Zuru, when filming resumed.[78] A broken dam and several floods also caused the surrounding lake to fill with sediment, adding six feet to its height.[23] Most of the set, ranch, editing equipment and film stock were destroyed; over $3 million of damage was caused,[45] though the negative had already been sent to be edited in a Hollywood studio.[79] Many friends and strangers offered help to the Marshalls and their crew, including the Southern Pacific Railroad office who offered to send railway cars as temporary housing for the animals.[80] As a result of the flood, production was halted for a year to allow the surrounding area to recover.[23] It took eight months to rebuild the set, and 700 replacement trees were purchased. After most of the issues resulting from the flood had been resolved, twelve wildfires in an Acton, California area broke out in September, though the animals remained unharmed.[81][38]

Music

Terence P. Minogue composed the film's score and recorded it with the National Philharmonic Orchestra.[82] Robert Florczak—credited in the film as Robert Hawk—provided vocals for original songs such as "Nchi Ya Nani? (Whose Land Is This)", a song with an African-pop style like others on the soundtrack.[82][83] Both musicians visited the set to seek inspiration,[84] and Minogue created the composition using a piano he brought to the family's ranch.[38] Percussionist Alexander Lepak used grinding drums and synthesizers to augment dialogue-free scenes, and Minogue's orchestral score was used in lighter scenes. Dominic Frontiere wrote a theme for Togar, the rogue lion. The soundtrack, originally released in 1981, became available online in 2005.[30]

Releases

Theatrical

Roar was not released theatrically in North America.[20][60][46] Hedren stated that it was not released in the United States because distributors wanted the "lion's share" of the profits, which she and Marshall had intended to allocate for the care of the film's animals.[21][23] Terry Albright, who was part of the film's crew throughout its production, said that another reason prohibiting the film's release in North America was because the crew was non-unionised, except for de Bont.[75]

While Roar was initially screened internationally on February 22, 1981, by Noel and John Marshall, its world premiere was held in Sydney, Australia on October 30, 1981.[85] The film was also picked up for a one-week distribution in Australia and the United Kingdom[46][86] by Filmways Pictures and Alpha Films,[87] the latter giving it the title Roar - Spirit of the Jungle.[2] The Marshalls also signed deals to release Roar in Japan, Germany, and Italy.[88]

Re-release

In 2015, 34 years after its initial release, Drafthouse Films founder Tim League expressed interest in the film and the company bought Roar's rights.[46] It began a limited theatrical run on April 17, 2015[3] at six theaters across the United States; the following month, distribution was expanded to 50 cities.[60] The Drafthouse re-release used promotional text in its trailers and press materials such as: "No animals were harmed during the making of 'Roar.' But 70 members of the cast and crew were", and called it the "snuff version of Swiss Family Robinson".[60] Hedren canceled an interview with the Associated Press after the Roar Foundation and Shambala Preserve's board of directors asked her not to speak publicly about the film, although she stated through a spokesman that its Drafthouse promotion was filled with "inaccuracies".[60]

Reception

Box office

Roar's worldwide gross (excluding the U.S.) was less than $2 million against its $17 million budget, making the film a box-office bomb.[7] Hedren had predicted that it would be a hit, projecting a gross of $125–150 million,[89] and claimed in 1982 that it was making $1 million a month.[90] Though it was popular in West Germany and Japan, performing well at the box office.[46][86] Despite this, John Marshall later said in a Grantland interview that "$2 million is a long way off" due to the film's success in West Germany and Japan; the latter's distributor paid $1 million, and Noel Marshall told him that the film made $10 million.[48] It had an opening weekend gross of $15,064 in its re-release, ending with a domestic gross of $110,048.[91]

Critical reception

Roar has an approval rating of 72% (based on 25 reviews) on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 5.77/10. According to the site's critical consensus: "Roar may not satisfy in terms of acting, storytelling, or overall production, but the real-life danger onscreen makes it difficult to turn away."[92] The film has a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 (based on 9 critics) on Metacritic, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[93]

The film received mixed reviews when it was first released. Although Variety praised its intended message ("a passionate plea" to preserve African wildlife), Roar was described as "a kind of Jaws of the jungle" which seemed "at times more like Born Free gone berserk"; its "thin" plot was also noted.[94] David Robinson believed he was obligated to dismiss the story and plot, instead choosing to compliment the "superb" animals in his review for The Times, and he was impressed by the depiction of the interactions between the humans and the animals in the film which "overturns centuries of preconceptions about relationships in nature."[95] Time Out, in a review published in 2004, disliked the film's "ingenuous documentary portrait of the Marshalls as mega-eccentrics and misguided animal lovers", and called its narrative a "farcical melange of pseudo David Attenborough and Disneyspeak" with "bizarre contradictions" and "fickle camerawork."[96]

Roar continued to receive mixed reviews after its 2015 re-release. Writing for RogerEbert.com, Simon Abrams rated the film a 2; the untrained big cats were the only assets in an "otherwise slack thriller", and some scenes were dull due to their emphasis on "Scooby Doo-like" chase scenes that focused more on the animals than on the plot, though Abrams concluded that for animal lovers, Roar was "worth seeing once".[97] Matt Patches, in his mostly positive review for Esquire, said the film worked as a "portrait of recklessness and beastly terror", akin to watching a Jackass movie; although "plotless enough" to give animals writing credits, Patches said the film was "shock cinema worth preserving".[4]

On a more negative note, Jordan Hoffman of The Guardian thought the film had little story to offer and described it as "a tad incoherent", picking up on Hank's confusing background. Hoffman criticized the film's dialogue, calling a scene of Hedren and Griffith discussing sexuality "undeniably creepy".[98] Amy Nicholson in LA Weekly observed the subjugation of the script to the boisterous impulses of the animal cast and noted that the actors seemed keen to get through their scenes quickly; this, she said, conflicted with the film's goal of proving "big cats are lovable".[99] Rene Rodriguez of the Miami Herald was displeased with the film's editing, saying it was "pasted together into a threadbare story", producing "a hysterically bad, awful movie".[100] Flavorwire included the re-release in their monthly "So Bad It's Good" review; writer Jason Bailey saw Roar as "a cross between a nature special, a home movie, a snuff film, and a key exhibit at a sanity hearing" with animals inflicting "horrifying bloodshed" before abruptly becoming "cuddly kittens, accompanied by a sappy string score" and said much of the film consisted of "odd, semi-improvised" dialogue.[5]

Legacy

He was always trying to get something going [...] But you work on something for 10 or 11 years, and you put everything you own into it, and every dime that anyone you know owns into it, and you're not doing anything with it because it's impossible? I think maybe it was just too hard and he got disillusioned.[48]

— John Marshall, on why his father Noel stopped making films

After its release, Roar's financial failure hindered the intended plan to fund the animals' retirement.[11] Marshall and Hedren had grown distant by the time production was completed, and they divorced in 1982.[44] Hedren founded the Roar Foundation, and established the Shambala Preserve sanctuary in Soledad Canyon in 1983 to house the animals after filming was completed.[101][44] As a result of establishing Shambala and rescuing more than 230 big cats, Hedren advocates animal rights and the preservation of natural habitat, and opposes animal exploitation.[102][67] Although Marshall continued to provide most of Shambala's financial support, according to John Marshall he "couldn't be with the animals that he loved and raised".[48] He never directed another film again and died in 2010.[3]

The film has been mentioned by authors Harry and Michael Medved in the 1984 book The Hollywood Hall of Shame as "the most expensive home movie ever made" due to its inflated budget.[103] Hedren wrote The Cats of Shambala, published in 1985, which told many behind-the-scenes stories and described the many on-set injuries.[60][67] Hedren stated in her book she and Noel realized that, while they accomplished their goal (to "capture wild animals in an astonishing and absolutely unique way"), the story was poorly made and secondary to "the actions, reactions and interactions of the big cats". She also said that the injuries inflicted on the crewmembers and cast were the result of putting their lives at risk to make the film. Hedren, however, noted a positive outcome for those who worked on Roar: many of the people involved went on to have successful careers or jobs in the film industry, such as de Bont and Griffith.[104] She later reflected on the film, saying that despite the danger, Roar had been worthwhile, but still called it "the toughest movie of my life".[4] Due to the many injuries on set, the film's re-release trailers and adverts called it "the most dangerous film ever made".[20] Since its original release, it has built up a cult following.[46][105]

Home media

A non-anamorphic version of the film was originally released on DVD[30] but, as stocks dwindled, it became a cult item and was listed at high prices on Amazon and eBay.[100] After its 2015 theatrical release in the United States,[106] the film was released in November 2015 by Olive Films for Blu-ray in anamorphic format. The Blu-ray bonus features included audio commentary by John Marshall and Tim League, "The Making of ROAR" featurette, and a Q&A with the cast and crew at Cinefamily in Los Angeles.[107] Drafthouse also authorized an at-home VOD release featuring a video Q&A with John Marshall. Ten percent of the profits went to the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation's Pioneers Assistance Fund, which in turn channel profits to theater employees affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.[108]

References

- Barnes, Mike (April 9, 2011). "Producer Chuck Sloan Dies at 71". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "Roar (1981)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- Bealmear, Bart (April 14, 2015). "'Roar': Cast and crew risked life and limb in the most dangerous movie ever made, 1981". Dangerous Minds. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Patches, Matt (April 2, 2015). "Looking Back at Roar, a Shocking, Lion-Filled 1981 Movie You've Never Seen (Yet)". Esquire. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Bailey, Jason (April 13, 2015). "So Bad It's Good: Tippi Hedrin's Insane Big-Cat Home Movie That Injured 70". Flavorwire. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 123, 156.

- Lumenick, Lou (April 11, 2015). "Son of 'Roar' director: 'He was a f—ing a–hole' for making us do the movie". New York Post. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Skinner, Oliver (June 29, 2015). "Beautiful Disasters: 'Roar'". Mubi. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 156, 157.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 172, 175.

- Feature Audio Commentary with John Marshall and Tim League. Olive Films. November 3, 2015.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 29.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 29, 156.

- "Dr. Kyalo Mativo - Obituaries". Hanford Sentinel. July 17, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 155.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 374.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 253, 372.

- Wurst II, Barry (March 5, 2016). "Roar". Hawaii Film Critics Society. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Hutchins, Will (March 2016). "Will Hutchins reminisces about Noel Marshall". Western Clippings. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Donovan, Sean (March 20, 2019). "Animalistic Laughter: Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar". CineFiles. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Paul 2007, p. 86.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 20.

- Grigonis, Richard (November 24, 2010). "Shambala Preserve, Acton, California". InterestingAmerica.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Christy, Marian (July 8, 1973). "No one can 'possess' Tippi Hedren". The Salina Journal.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 184–187.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 188–189, 202.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 159.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 185–187.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 30.

- Hasan, Mark R. (June 18, 2015). "Film: Roar (1981)". KQEK.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 140, 186.

- Barnard, Linda (April 17, 2015). "Cult animal disaster movie Roar to play Toronto". The Star. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 52–54.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 221, 236–237.

- Hedren 2016, p. 239, 250–251.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 80, 152.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 81.

- Peters, Clinton Crockett (October 9, 2018). "The Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made". Electric Literature. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 73, 153, 164.

- Frye, Carrie (October 19, 2012). "How To Get Your Lion Back When It Runs Away: Life Lessons From Tippi Hedren". The Awl. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Hedren 2016, p. 337.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 254–255, 287.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 190–191.

- Gindick, Tina (September 26, 1985). "The Lion's Share of the Good Life : Tippi Trades Roar of the Greasepaint for the Real Thing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- Onda, David (July 9, 2015). "The Unbelievable True Stories Behind 'Roar,' the Most Dangerous Film Ever Made". Xfinity. Archived from the original on August 1, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- Buder, Emily (July 7, 2015). "'Holy F*cking Sh*t' Discovery of 'Roar,' the Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made". IndieWire. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 145.

- Pappademas, Alex (April 17, 2015). "'We'd All Been Bitten, and We Kept Coming Back': 'Roar' Star John Marshall on Making the Most Dangerous Movie of All Time". Grantland. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- Schmidlin, Charlie (April 6, 2015). "70 People Were Harmed in the Making of This Film". Vice. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- Nicholson, Amy (April 28, 2015). "Roar Is an Animal Anti-Masterpiece". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 146.

- Yamato, Jen (April 11, 2015). "'Roar': The Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made". The Daily Beast. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Dangaard, Colin (September 27, 1977). "Cost of 'Roar' measured in cast's blood, anguish". The Montreal Gazette.

- Stobezki, Jon (February 19, 2015). "Utterly Brainsick ROAR, Starring Tippi Hedren & Melanie Griffith, Joins Pride Of Drafthouse Films". Drafthouse Films. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 359–360.

- Collis, Clark (April 15, 2015). "Fifty Shades of Grrrrrr: The insane story of 'Roar'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 164.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 179–181.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 389.

- Bahr, Lindsey (April 16, 2015). "'Roar': 'Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made' Charges Into Theaters". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 451.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 397–399.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 461.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 258.

- "Lion Mauls Man On Set". Panama City News Herald. July 9, 1978.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 205–207.

- Gambin 2012, And A Frog Shall Lead Them: Mother Nature Gets Angry As Humankind Panics.

- Welk, Brian (March 11, 2015). "Watch a trailer for the re-release of 'Roar', the most dangerous film ever made". Sound on Sight. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 341–345.

- Lewis, Roz (December 3, 2016). "Actress Tippi Hedren: 'The tiger came at me - its jaws were round my head'". The Telegraph. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Tippi Hedren Learns the Law of the Jungle: When An Elephant Decides to Ad Lib, Look Out". People. July 11, 1977. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- "Elephant Didn't Read The Script". Kingsport Times-News. June 19, 1977.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 195.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 384–385.

- Allegre, David (April 24, 2015). "'Roar' Crewmember Recounts Dangerous Production Fondly". Scene Stealers. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "Lion Mauls Man On Film Set". Santa Cruz Sentinel. July 9, 1978.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 423–424, 430–432.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 232.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, p. 223.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 434.

- Hedren 2016, p. 457–460.

- Dursin, Andy (November 10, 2015). "Aisle Seat 11-11: The November Rundown". Film Score Monthly. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- McArthur, Andrew (August 8, 2015). "EIFF2015 Review – Roar (1981)". The People's Movies. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Hedren 2016, pp. 463.

- Hedren 2016, p. 464–466.

- Whittaker, Richard (April 29, 2015). "Roar: The Blood Stays in the Picture". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- Dirks, Tim (April 15, 2008). "Greatest Box-Office Bombs, Disasters and Flops: The Most Notable Examples". Filmsite.org. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Hedren 2016, p. 464.

- Kornheiser, Tony (August 17, 1979). "After 'The Birds,' Beauty Turns to Beasts". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- Knickerbocker, Suzy (March 24, 1982). "Hedren's Marriage Ends". Syracuse Herald-Journal.

- "Roar! - (2015)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- "Roar (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "Roar Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- "Roar". Variety. December 31, 1980. Archived from the original on July 19, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Robinson, David (April 2, 1982). "Cinema". The Times. p. 17.

- "Roar". Time Out. December 5, 2004. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- Abrams, Simon (April 17, 2015). "Roar Movie Review & Film Summary (2015)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- Hoffman, Jordan (April 14, 2015). "Roar review: big cat movie that injured 70 crew is re-released! Run! Towards it!". The Guardian. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- Nicholson, Amy (April 15, 2015). "A Celebrity Family Adopted 150 Dangerous Animals to Make This Movie — and It Nearly Killed Them". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- Rodriguez, Rene (April 30, 2015). "'Roar' (PG)". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on July 8, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- "Living with lions". The Economist. May 5, 2015. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- Reardanz, Karen (July 30, 2015). "Tippi Hedren: 'Lion killing affected me physically'". SFGate. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- Medved & Medved 1984, p. 224.

- Hedren & Taylor 1988, pp. 260, 285–286.

- "ROAR: The Most Dangerous Movie Ever Made". Rio Theatre. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- Logan, Elizabeth (February 19, 2015). "Drafthouse Films Acquires '80s Cult Classic 'Roar,' Plans Theatrical Release". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- Tooze, Gary (October 31, 2015). "Roar [Blu-ray]". DVDBeaver. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- Collis, Clark (April 7, 2020). "Hollywood's real Tiger King: Insane big cat movie Roar getting VOD rerelease". EW. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

Bibliography

- Gambin, Lee (October 8, 2012). Massacred By Mother Nature: Exploring the Natural Horror Film. Midnight Marquee Press, Inc. ISBN 978-1936168309.

- Hedren, Tippi; Taylor, Theodore (August 1, 1988). The Cats Of Shambala (Reissue ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780963154903.

- Hedren, Tippi (November 1, 2016). Tippi: A Memoir. ISBN 978-0062469038.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Medved, Michael; Medved, Harry (July 1, 1984). The Hollywood Hall of Shame. HarperCollins. ISBN 0207149291.

- Paul, Louis (2007). Tales from the Cult Film Trenches: Interviews with 36 Actors from Horror, Science Fiction and Exploitation Cinema. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786429943.