Robert Craufurd

Major-General Robert Craufurd (5 May 1764 – 23 January 1812) was a British soldier. Craufurd was born at Newark, Ayrshire, the third son of Sir Alexander Craufurd, 1st Baronet (see Craufurd Baronets),[1] and the younger brother of Sir Charles Craufurd. After a military career which took him from India to the Netherlands, in 1810 in the Napoleonic Peninsular War he was given command of the Light Division, composed of the elite foot soldiers in the army at the time, under the Duke of Wellington. Craufurd was a strict disciplinarian and somewhat prone to violent mood swings which earned him the nickname "Black Bob". He was mortally wounded storming the lesser breach in the Siege of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19 January 1812 and died four days later.

Major General Robert Craufurd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Black Bob |

| Born | 5 May 1764 Newark Castle, Ayrshire, United Kingdom |

| Died | 23 January 1812 (aged 47) Ciudad Rodrigo, Spain |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Rank | Major general |

| Relations | Craufurd baronets |

Early life

Like Sir John Moore, the Craufurd family originated from Ayrshire. Alexander Craufurd lived at Newark Castle, and Thirdpart, Ayrshire. They were the cadet line of the Craufurds of Auchenames represented the old line of the Craufurds of Loudoun. The castle was sold by Alexander's grandfather, who was a friend of the Duke of Buccleuch, and then went to live in England in Essex. He was created a baronet in 1781. His eldest son became Sir James, the second baronet. Robert's sibling and second brother, Charles was also a British Army soldier.

Career

Military prodigy

Craufurd entered the army aged fifteen. He enlisted as an Ensign with the 25th Foot in 1779,[2] serving four years as a subaltern. By aged nineteen he was already a company commander. He spent some time at Berlin in 1782, studying the tactics of the army of Frederick the Great and translated into English the official Prussian treatise on the Art of War. Together with his brother Charles, he attended King Frederick the Great's Review of the troops at Potsdam by personal invitation.

As captain in the 75th Regiment from 1787, he first saw active service against Tippoo Sahib in 1790–92, while serving under Lord Cornwallis. His distinguished service was praised earning seniority in Captaincies among the purchased commissions. Robert returned to England on leave to help his brother, Colonel Charles. His knowledge of German, a rare accomplishment in the British Army at the end of the eighteenth century, caused him to the given the post of military attaché at Coburg's headquarters of the Austrian army in 1794 to 1796.[3]

In 1798 Craufurd was sent as Deputy Assistant Adjutant General on General Lake's staff to quash the Irish rebellion against General Humbert.[2] His abilities were recognised by Generals Cornwallis and Lake who reported well of his performance to the War Office. A year later, due to his German language skills, he was British commissioner on Suvorov's staff when Russia invaded Switzerland. At the end of 1799, Craufurd was on the staff in the Helder Expedition led by the Duke of York.

Family life

Robert had married on 7 February 1800 at St Saviour's Church, Mary Frances, daughter of Henry Holland, Esquire of Hans Place, Chelsea, and granddaughter of the landscape designer Lancelot "Capability" Brown. He was very fond of his wife, and, to the exasperation of his General officer commanding, regularly requested 'furlough' home to see his young love. At the time he often talked to family of retiring from the army altogether. It was also at this time that he developed a correspondence with the Secretary at War, William Windham. They became firm friends. From 1801 to 1805, Craufurd (by then a lieutenant-colonel) sat in parliament for East Retford, but in 1807 he resigned to concentrate on soldiering.

The Buenos Aires Expedition

On 30 October 1805, Craufurd was promoted to full colonel and put in command of his own regiment. He was ordered on an expedition to South America. In 1806 on the promise of another promotion to Brigadier-general he took ship to Rio de Janeiro. The British commander-in-chief General Whitelocke was based at Montevideo. Craufurd's brigade was two squadrons of 6th Dragoon Guards, the 5th Dragoon Guards, 36th Regiment, 45th Regiment, and 88th Regiments of Foot, and five companies of 95th Rifles, totaling 4,200 men. The broad objective was the conquest of Chile. Craufurd departed from Falmouth docks on 12 November 1806, sailing south to the Cape of Good Hope with Instructions from William Windham. General Samuel Auchmuty and Admiral Murray were despatched to report back to the Pittite ministry, who wanted the capture of Buenos Ayres. They had already left London on 9 October.

The flotilla arrived with 8,000 men on board on 15 June 1807, when the armies were finally united at Buenos Aires. Whitelocke refused to act, and was accused by Robert Craufurd of cowardice. He was supported in London by his brother Charles, who had a network of aristocratic contacts. Whitelocke would not countenance an attack on General Liniers army. The British advanced into the town; Craufurd wrote he wanted to attack the ramparts, but was prevented by the superior officer. The Spanish colonial forces retreated, retrenched the streets and deployed heavy artillery. Craufurd's brigade was forced to retreat to the Convent of Saint Domingo, they could hear the guns fall silent; his brigade was surrounded by 5,000 of the enemy and forced to surrender at 4 pm.[4][5] A total of 1,070 officers and men were killed or severely wounded; Craufurd and Coadjutor Edmund Pack of Royal Horse Guards were incensed. They offered to shoot the 'traitor' when they returned to Hythe:[6] Whitelocke compounded the treason when Liniers offered to return prisoners and 71st Regiment; he agreed and surrendered Montevideo, also promising to withdraw from the River Plate.

Writing in 1891 the biographer Alexander Craufurd states that General Craufurd, and apparently many other officers were "under the impression that Whitelocke was a traitor as well as a time and vacillating fool, but I have failed to find in the account of the court-martial any solid evidence in support of this impression".[7]

Peninsular campaigns

In October 1808, Craufurd sailed for Corunna with Sir David Baird's contingent to reinforce the army under Sir John Moore. Moore had marched his forces by several routes to Salamanca. The two forces joined up at Mayorga on 20 December 1808. Moore was then able to reorganise the army and Craufurd was given command of the 1st Flank Brigade, composed of the 1/43rd, 1/52nd and 2/95th. Intelligence revealed that, apart from the corps of Marshal Soult to his front, Napoleon was advancing at speed from Madrid. Moore was fearful that the army could be overwhelmed by much superior forces and their line of retreat to the sea, some 250 miles more to port evacuation, could be cut off. On 24 December he order the retreat to Corunna. Craufurd’s Brigade formed part of the rearguard under Maj. General Sir Edward Paget. His regiments were heavily engaged in the earlier part of the retreat. The Commissariat was delayed. There was no food. In freezing winter snow and fog they marched at double-quick pace fighting off much larger forces. On 31 December Moore ordered the army to divide. The two Flank Brigades of Craufurd (with 1,900 men) and Brigadier Charles Alten (with 1,700 men) were ordered along a southerly route via Orense to Vigo while the main column continued on the Corunna Road.[8]

On New Years Day 1809, they climbed the steep mountain passes. Men died in the snow of hunger, others found food along the way.[9] It became a trial of the greatest intensity, although it was only the road and the elements against which they had to battle; they were not pursued by the French. A week later at Orense they were starving, marching in rags. They reached the port on 12th but awaited for stragglers before embarking for England.[2]

An important Memoir was that from Rifleman Harris, whose eloquence was descriptive. He expressed the men's pride in the courage, despite severe discipline of the officers.[10]

Craufurd had "a severe look and a scowling eye", wrote Harris.[11] William Napier thought the brigadier "very attentive to the men".[12] But "willfulness and folly" was treated very severely by lashings.[13] Unusually for so harsh a disciplinarian, Craufurd was admired and trusted by his men and Harris had no doubt about his role in saving his command: "No man but one formed of stuff like General Craufurd could have saved the brigade from perishing altogether; and if he flogged two, he saved hundreds from death by his management … He seemed an iron man; nothing daunted him – nothing turned him from his purpose. War was his very element and toil and danger seemed to call forth only an increasing determination to surmount them … I shall never forget Craufurd if I live for a hundred years I think. He was in everything a soldier."[14]

On 25 May 1809, Craufurd embarked at Dover for Portugal with his brigade consisting of the 43rd Foot, 52nd Foot and the 95th Rifles. Delayed at The Downs and Isle of Wight by bad weather, they arrived three weeks later on 18 June. Had they been on time Craufurd's force might have joined Wellington at Talavera. At Lisbon the brigade purchased packhorses, and accompanied by Capt Hew Ross' troop of Horse Artillery, they marched to join the main army. By 20 July they had reached Zarza Mayor and on 22 July were at Coria. On the 27th the Light Brigade marched to Navalmoral. Before dawn on the morning of the 28th Craufurd started his attempt to join Sir Arthur Wellesley before the French attacked him at Talavera. The march which followed is one almost unparalleled in military annals. Whilst the distance 'as the crow flies' from Navalmoral to Talavera is a little over thirty-eight miles, the actual marching distance is about forty-two miles and probably more owing to the turn and windings of the road. In the full heat of Spanish summer and in full regimental kit, the soldiers suffered from a terrible thirst. Their march was driven on by the growling of the cannon in the distance and they left only a few weakly men at Oropesa. In spite of covering about 45 miles in 26 hours, Craufurd arrived too late to participate in the battle.[15]

In early 1810 Wellington obtained intercepted secret letters from Marshall Soult to the King of Spain of the planned attack on Ciudad Rodrigo. The bulk of the army was moved into northern Portugal. On 1 March Craufurd’s Light Brigade become The Light Division. Initially he had 2,500 men from the first battalions of the 43rd, 52nd and 95th together with a troop of horse artillery and one regiment of 500 cavalry from the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion. On 28 March these were augmented by 1,000 men from two battalions of Portuguese Caçadores, the 1st and 2nd. The latter of these units was afterwards changed for the 3rd, which was reckoned the most efficient corps that could be selected from Marshal Beresford's command. The cavalry force was also increased by two squadrons of the 16th Light Dragoons and, in early July, by the addition of three squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons.

Robert Craufurd, though only a brigadier, and junior of his rank, had been chosen by Wellington to take charge of his outpost line because he was one of the very few officers then in the Peninsula in whose ability his Commander-in-Chief had perfect confidence. Only with Craufurd, Hill and Beresford, did he ever condescend to enter into explanation and state reasons. In one letter to Craufurd, Wellington writes "Nothing can be of greater advantage to me than to have the benefit of your opinions on any subject."

In 1810 Craufurd was burning to vindicate his reputation and show that the confidence which Wellington placed in him was not undeserved. He could not forget that he was four years older than Beresford, five years older than Wellington, eight years older than Hill, yet but a junior brigadier-general in charge of a division. Though senior in the date of his first commission to nearly all the officers in the Peninsular Army. Craufurd was six years junior to Picton and one year junior to Hope.[16]

The Light Division was pushed forward to the Spanish frontier, and lay in the villages about Almeida, with its outposts pushed forward to the line of the River Águeda. From March to July 1810 Craufurd accomplished the extraordinary feat of guarding a front of 40 miles against an active enemy of six-fold force, without suffering his line to be pierced, or allowing the French to gain any information whatever of the host in his rear. He was in constant and daily touch with Ney’s corps, yet was never surprised, and never thrust back save by absolutely overwhelming strength; he never lost a detachment, never failed to detect every move of the enemy, and never sent his commander false intelligence. This was the result of system and science, not merely of vigilance and activity.

Whilst there were four bridges, there were also some fifteen fords between Ciudad Rodrigo and the mouth of the Águeda, which were practicable in dry weather for all arms, and several of them could be used even after a day or two of rain. Special report were made of the state of the fords every morning and the rapidity of its rises was particularly marked. Beacons were prepared on conspicuous height so as to communicate information as to the enemy' offensive movements. As Napier remarked in his History, seven minutes sufficed for the division to get under arms in the middle of the night, and a quarter of an hour, night or day, to bring it in order of battle to its alarm posts, with baggage loaded and assembled at a convenient distance to the rear.

The first test of the efficiency of Craufurd’s outpost system was made on the night of 19–20 March, when Ferey, commanding the brigade of Loison’s divisions which lay at San Felices, assembled his six voltigeur companies before dawn and made a dash at the old Roman bridge of Barba del Puerco. He had the good luck to bayonet the sentries at the bridge before they could fire and was halfway up the rough 230 metres ascent from the bridge to the village (today called Puerto Seguro), when Beckwith's detachment of the 95th Rifles, roused and armed in ten minutes were upon him. They drove him down the defile and chased him back across the river with the loss of two officers and forty-five men killed and wounded. Beckwith’s riflemen lost only one officer with three men killed and ten men wounded from the three companies engaged.[17]

Craufurd's operations on the Coa and Águeda in 1810 were daring to the point of rashness; the drawing on of the French forces into what became the Combat of the Coa in particular was a rare lapse in judgement. Although Wellington censured him for his conduct, he later wrote “... I cannot accuse a man who I believe has meant well, and whose error was one of judgement, not of intention." [see Craufurd’s Life pp. 149–50]

The conduct of the renowned Light Division at Bussaco is described by Napier in one of his most vivid passages.[18]

The winter of 1810–1811, Craufurd spent in England, and his division was commanded in the interim by another officer. He reappeared on the field of the Fuentes de Oñoro to the cheers of his men.[18] Wellington had left the 7th Division exposed on his right flank. On 5 May 1811 Masséna launched a heavy attack on the weak British-Portuguese flank, led by Montbrun's dragoons and supported by the infantry divisions of Marchand, Mermet, and Solignac. Right away, two 7th Division battalions were roughed up by the French light cavalry. This compelled Wellington to send reinforcements to save it from annihilation. This was only achieved by the efforts of the Light Division and the British and King's German Legion cavalry who made a textbook fighting withdrawal.[19]

Robert Craufurd was promoted to Major-General on 4 June 1811.

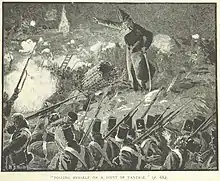

Death at Ciudad Rodrigo

On 19 January 1812, as he stood on the glacis of Ciudad Rodrigo, directing the stormers of the Light Division, he fell mortally wounded. His body was carried out of action by his staff officer, Lieutenant Shaw of the 43rd, and, after lingering four days, he died.[18]

He was buried in the breach of the fortress where he had met his death, and a monument in St Paul's Cathedral commemorates Craufurd and Mackinnon, the two generals killed at the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo.[18]

Major-General Craufurd was nicknamed 'Black Bob'. The nickname is supposed to refer to his habit of heavily cursing when losing his temper, his nature as a strict disciplinarian and even to his noticeably dark and heavy facial stubble. During the First World War, a Lord Clive class monitor was named for him, HMS General Craufurd.

Notes

- Craufurd 1891, p. 2.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 382.

- Oman, vol III, pp.233-4

- Craufurd 1891, p. 21 cites Cole, "Distinguished Peninsular Generals"

- Craufurd 1891, p. 21.

- Craufurd 1891, p. 23 cites Harris "Recollections"

- Craufurd 1891, p. 23.

- Craufurd 1891, p. 41.

- Craufurd 1891, pp. 41–42.

- Craufurd 1891, p. 44.

- Craufurd 1891, p. 45 cites Harris "Recollections"

- Craufurd 1891, p. 48 quoting a letter by William Napier dated 11 November 1808

- Craufurd 1891, p. 48.

- Rifleman Harris pp.92-93, 102

- Willoughby Verner, chapter IV

- Oman, vol III, pp. 232-5

- Oman, vol III, pp.236-8

- Chisholm 1911, p. 383.

- Oman, vol IV, pp324-7

References

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Craufurd, Alexander Henry (1891), General Craufurd and his light division, with many anecdotes, a paper and letters by Sir John Moore, and also letters from the Right Hon. W. Windham, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Londonderry, and others, London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh Notes:

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Craufurd, Alexander Henry (1891), General Craufurd and his light division, with many anecdotes, a paper and letters by Sir John Moore, and also letters from the Right Hon. W. Windham, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Londonderry, and others, London: Griffith, Farran, Okeden & Welsh Notes:

- Cole, John, Distinguished Peninsular Generals

- Costello, Sergeant Edward, Adventures of a Soldier

- Harris, Daniel, Recollections of Rifleman Harris

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Craufurd, Robert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 382–383.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Bruce, N A. (1864). Life of Sir William Napier.

- "Quartermaster John Surtees"

- Alison, Walter (1848). History of Europe.

- Kincaid, Colonel. Random Shots of a Rifleman. Project Gutenberg.

- Craufurd, Alexander (1906). General Craufurd and His Light Division.

Secondary sources

- Oman, Sir Charles (1902–30). A History of the Peninsular War (7 volumes). The Clarendon Press.

- Verner, Colonel Willoughby (1912). History & Campaigns of The Rifle Brigade Vol.I. John Bale, Sons & Danielsson.

- Hibbert, Christopher, ed. (1996). The Recollections of Rifleman Harris. The Windrush Press. ISBN 0-900075-64-3.

External links

- Stephens, Henry Morse (1888). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 14, 15.