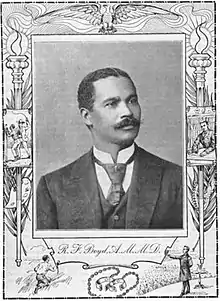

Robert F. Boyd

Robert Fulton Boyd (1858-1912) was a medical doctor, dentist, pharmacist, professor, teacher, politician, and most notably, the co-founder and first president of the National Medical Association. He was a man of many talents, infinite curiosity and compassion who multifariously impacted the lives of the communities he was a part of, all while remaining humble. He fought political oppression by involving himself in local politics, and racial segregation in healthcare, faced by the black community in the 19th century, leaving a permanent mark on the American medical community. Although his life was cut short, Boyd nonetheless enlightened the people around him, inspiring education and healthcare.

Robert Fulton Boyd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 July 1858 |

| Died | 20 July 1912 |

| Education | Central Tennessee College, University of Chicago |

| Title | M.D. |

Early life

Boyd was born in Giles County, Tennessee, on July 8, 1858, as the son of two slave parents;[1] Maria Coffet and Edward Boyd.[2] At a young age he worked at the farm where his parents were placed; however, he never really lived with his mother as during the American Civil War she was carried South, and remained there until 1866.[3] In 1866, she returned to Giles County to take her two children with her, Dr. Boyd being the oldest, to Nashville[3] and sent Boyd to live with Dr. Paul F. Eve, one of the greatest surgeons of the time.[1] At the age of 13 he acquired formal education from the public schools in Pulaski.[1]

Education

Living with Dr. Eve gave him the chance to attend night classes at Old Fisk School (now Fisk University), which was a decisive step for his life choice of becoming a physician.

A few years later, in 1872 he began working and studying at the same time: he worked half of the day for the real estate agent General James H.Hickman. At this time he was paid in meals, receiving no wages and carrying on his school career during the other half of the day.[2][3]

Later on, in 1876, while attending college, Boyd began involving himself in teaching activities: he started by teaching, and then became principal of the "Public School for Negroes" in Pulaski; he eventually was able to open a night school and teach to adults, but teaching was still a leisurely occupation for him.[1]

After his experiences in teaching, in 1880 Boyd entered the medical department of Central Tennessee College and graduated there with honours in 1882. Subsequently, he acquired the position of principal in a school in New Albany, Mississippi.[2] After some years, he decided to start working as an adjunct professor of chemistry at Nashville's Meharry Medical College, and, simultaneously, he entered the new dental department of Central Tennessee College, graduating with honours in 1886.

When he returned to Nashville he became assistant surgeon to Dr. Eve, his early role model and teacher.[2] In the summer of 1890, Boyd attended The University of Chicago as a scholar of the Postgraduate School of Medicine and in 1891 he received the Master of Arts degree from Central Tennessee College.[2] In 1892 he returned to the University of Chicago to specialise in diseases of women and children.[2]

Work and research

Early work

After three years of employment at General Hickman's real estate agency, Boyd quit as his aspirations were for another career.[2] In the early summer of 1875, he began a short teaching career at College Grove in Williamson County, he returned to Giles County only the following year.[2] By 1876 he rose from teaching in county schools to achieving principalship of 170 male students in Pulaski, and in 1878 and 1879 he was the principle of the female department as well.[3] He distinguished himself thanks to his enthusiastic energy and conscientious spirit.[2][3]

Work in the medical field

After graduating from Tennessee College, Dr. Boyd went to New Albany, Mississippi, where he took the principalship of a high school and practiced medicine till the fall of 1882.[3] Just few months later, he returned to Nashville. Upon his return he was made assistant professor of chemistry at Meharry Medical Department of the Central Tennessee College.[3] While employed there, he enrolled in Meharry's Dental Department and graduated with a degree in dentistry in 1886.[4] His teaching career at Meharry College would be a long one lasting until his untimely death in 1912 and he would work in a variety of departments, all listed in the table below.[3]

Summary of positions held

| Positions Held by Dr. Boyd at Meharry Medical College[5] | |

|---|---|

| Position | Year |

| Adjunct Professor of Chemistry | 1882-1884 |

| Professor of Physiology | 1884-1888 |

| Professor of Anatomy and Physiology | 1888-1889 |

| Professor of Physiology and Hygiene | 1889-1890 |

| Professor of Physiology, Hygiene, and Clinical Medicine | 1890-1893 |

| Professor of Diseases of Women and Clinincal Medicine | 1893-unknown |

On June 11, 1887, Dr. Boyd opened an office on North Cherry Street, Fourth Avenue, in Nashville to practice medicine and dentistry among the less fortunate. At the time double degrees weren't uncommon, as the first class to graduate from the School of dentistry at Meharry were already M.D.[1] He did not cater to the “better classes who were able to employ experienced and well known physicians,” instead he was adamant in providing care to those who could not afford it.[4] In addition to practicing medicine he also taught the members of these communities on causes, treatments, and prevention of tuberculosis.[2] People reported that "he [did] more work than any other physician in Nashville".[3] By the early 20th century he was treating patients in all socio-economic classes.[2]

In 1893 he ran for mayor and for a seat in the Tennessee General Assembly for the republican party. His specialisation in diseases of women and children allowed him to become professor of gynaecology and clinical medicine in Meharry in 1893.[2] During his time in Chicago it was also said that he worked for the largest hospitals and under the greatest men of the profession, which widened his skillset and abilities.[3] At this time he also dedicating two hours, three days a week to take care and visit the sick and poor.[3]

Dr. Boyd was also involved in a variety of fraternal societies and held high ranks within them: he held the title of Supreme Medical Register for the Coloured Knights of Pythias.[4] He became adamant, along with ten other coloured physicians, to create a national fraternity for black doctors.[1] He personally and actively took part in the creation of the National Medical Association, which was founded in 1895, and later became the biggest organisation for black patients and doctors. He became the first president in the founding year up until 1898.[4]

During this time Central Tennessee College had been attempting to secure funds for a teaching hospital. Before succeeding in their efforts a hospital opened near the school where the black students and staff of the university were welcomed for treatment and training.[2] Unfortunately, the city abruptly suspended permission for the wards and clinics to care for them. For this reason Dr. Boyd opened Mercy hospital in 1900.[2] He was 'superintendent' and 'surgeon in chief' of the Mercy Hospital up until 1912. As a pioneer in his field many black surgeons trained at Mercy Hospital and went on to open hospitals of their own throughout the South. Unfortunately his hospital was burned down, but he resiliently built the Boyd Infirmary in its place.[1]

Towards the end of the 19th century his reputation grew exponentially outside of Tennessee, he was offered for the office of Surgeon-in-chief at Freedmen's Hospital, in Washington D.C. Towards the end of his life he had surgical clinics in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Texas and Tennessee.[1]

Publication

“What are the Causes of the Great Mortality Among Negroes in the Cities of the South, and How is That Mortality to be Lessened?"[5]

Dr. Boyd was alarmed by what he saw while working in Nashville, he realised the shockingly high mortality rate of African Americans in the area which was far higher than that of their white counterparts. This pushed him to publish a study with some of the earliest and most astute observations regarding the conditions of African-Americans, and he also searched for medical solutions to his identified conditions.[2]

Personal life

In the 1890s, Boyd acquired a three-story brick house, of $14,000 value, on Cedar Street, which was renowned for one of the most popular hotels in the area: Duncan House. This was reputedly the most expensive house bought by a person of African descent in Tennessee up to that date.[1]

In 1909 Boyd was elected as president of the People's Savings Bank and TrustCompany, Nashville's African-American banks.[2]

In 1892, Dr. Boyd was added on the Republican ticket of the General Assembly of Tennessee.[1] A year later, the Democratic and Republican Executive Committees refused Black voters, and did not give them the right to nominate candidates for Mayor and City Council.[1] The African American community opposed the Executive Committees' choice by holding a mass meeting to protest this insult and inaugurate a Citizens' ticket.[1] Following this event, Dr. Boyd was unanimously nominated as the number one candidate for the position of Mayor of Nashville.[1] A Nashville citizen commemorated the importance of this happening at the time "the ticket received the support of the registered coloured voters and forever silenced the guns of our would-be disfranchisers".[1]

Boyd was a fraternity man, ranking high in various societies (elite and not). He was an honourable man that did anything that could help improve the livelihoods of the community in which he lived.[1] At Meharry Medical College he was president or treasurer of most societies.[1] He was also an active member of St. Paul A.M.E. Church (Raleigh, North Carolina), he received an honorary certificate of membership at the Anthropological Society of London, and was a member of the Congress of Coloured People.[1]

Death

Boyd died a sudden death on July 20, 1912, at the age of 54, after an "attack of acute indigestion". His funeral services were held in the Ryman Auditorium, and his body was buried in Nashville's Mt. Ararat Cemetery.[1] At the time of his death, he was considered the leading African-American physician in the United States, and supposedly the wealthiest.[1]

Historical context

The historical context under which Boyd lived and worked is essential to understand his struggles and recognise his achievements. He lived at a time when newly freed African Americans experienced great amounts of racism, violence, and segregation. He came from a background of slavery and illiteracy, after struggling to achieve his early educational requisites he was halted by the closed door policies established by medical colleges and hospitals at the time.[4] "The Negro doctor has had to struggle in a fashion and with a persistency rarely, if ever, equaled by any other group seeking professional status”.[6]

References

- "Robert Fulton Boyd". Journal of the National Medical Association. 45 (3): 233–234. May 1953. ISSN 0027-9684. PMC 2617285. PMID 13053213.

- "Robert Fulton Boyd". ww2.tnstate.edu. Retrieved 2021-04-29.

- Haley, James T.; Washington, Booker T.; Settle, William B.; Woodson, Carter Godwin (1895). Afro-American encyclopaedia, or, The thoughts, doings, and sayings of the race : embracing addresses, lectures, biographical sketches, sermons, poems, names of universities, colleges, seminaries, newspapers, books, and a history of the denominations, giving the numerical strength of each : in fact, it teaches every subject of interest to the colored people, as discussed by more than one hundred of their wisest and best men and women : illustrated with beautiful half-tone engravings. Robert W. Woodruff Library Emory University. Nashville, Tenn.: Haley & Florida – via Association for the Study of African-American Life and History.

- Morris, Karen Sarena (2007). The Founding of the National Medical Association (MD thesis). Yale University School of Medicine – via Elischolar.

- Twentieth century Negro Literature or a cyclopedia of thought on the vital topics relating to the American Negro. Library of Alexandria. 1969. ISBN 978-1-4655-6123-7.

- Lynk, Miles V. (1951). Sixty years of medicine, or, The life and times of Dr. Miles V. Lynk: an autobiography. Twentieth Century Press. OCLC 29644519.