Bob Ney

Robert William Ney (born July 5, 1954) is an American politician from Ohio. A Republican, Ney represented Ohio's 18th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1995 until November 3, 2006, when he resigned. Ney's resignation took place after he pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy and making false statements in relation to the Jack Abramoff Indian lobbying scandal. Before he pleaded guilty, Ney was identified in the guilty pleas of Jack Abramoff, former Tom DeLay deputy chief of staff Tony Rudy, former DeLay press secretary Michael Scanlon and former Ney chief of staff Neil Volz for receiving lavish gifts in exchange for political favors.

Bob Ney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 18th district | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – November 3, 2006 | |

| Preceded by | Doug Applegate |

| Succeeded by | Zack Space |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 20th district | |

| In office January 10, 1984 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Sam Speck |

| Succeeded by | James E. Carnes |

| Member of the Ohio House of Representatives from the 99th district | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – December 31, 1982 | |

| Preceded by | Jack Cera |

| Succeeded by | Wayne Hays |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert William Ney July 5, 1954 Wheeling, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Liz Ney (divorced) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Ohio University Eastern Campus Ohio State University (BS) |

Ney's best-known congressional work was on the election reform efforts founded in the wake of the confused 2000 voting in Florida, and his support and backing for the "Stand Up For Steel" crusade and resulting laws. From 2001 to 2006, Ney was Chairman of the House Administration Committee. As chair of that committee, he oversaw operations in the Capitol complex and was sometimes known as the "Mayor of Capitol Hill".[1]

Early life, education, and early career

Ney was born in Wheeling, West Virginia. The son of a TV cameraman for WTRF-TV, Ney grew up in Bellaire, Ohio, an industrial town across the Ohio River from Wheeling. He graduated in 1972 from St. John's High School in Bellaire. He attended Ohio University Eastern Campus in Belmont County before transferring to Ohio State University in Columbus. He received a Bachelor of Science degree from OSU in 1976.

After college, he worked at the Bureau of Motor Vehicles, taught English in Iran, served as Bellaire safety director, and worked as the health and education program manager of the Ohio Office of Appalachia.

He has two children from a previous marriage, and no children with his second wife, Elizabeth.

Early political career

In 1980, at the age of 26, Ney defeated state Representative Wayne Hays, a former U.S. representative who had resigned from Congress in 1976 after a sex scandal. Ney served in the Ohio House of Representatives from 1981 to 1983. He was defeated in his reelection bid in November 1982.

After his defeat, Ney managed a home security company in Saudi Arabia. He was appointed to the Ohio Senate in 1984 to replace former state senator Sam Speck, who resigned the 20th District seat to accept a presidential appointment. Ney won the seat in November 1984 and then re-election in 1988 and 1992.

U.S. House of Representatives

Elections

- 1994

In November 1994, Ney decided to run for Ohio's 18th congressional district after nine-term incumbent Democrat Douglas Applegate announced his retirement. Ney won the six-candidate Republican primary field with 69% of the vote.[2] The 18th had a considerable Democratic lean, but Ney scored a considerable upset, defeating Democratic State Representative Greg DiDonato 54%–46%.[3]

- 1996

In 1996, he won re-election to a second term, defeating Democratic State Senator Rob Burch 50%–46%.[4]

- 1998–2004

He went on to win re-election four more times easily without difficult competition in 1998 (60%), 2000 (64%), 2002 (unopposed), and 2004 (66%).

- 2006

On January 26, 2006, Ney announced his candidacy for re-election to a seventh term.[5] Even before his indictment, Ney was one of the Republican elected officials whom Democrats highlighted as part of a "culture of corruption" in the 2006 campaign.[6][7][8]

For the first time since 1994, he drew a primary challenger. Republican James Brodbelt Harris, a financial analyst from Zanesville, Ohio, decided to challenge him in 2006. Harris did not campaign, and collected less than $5,000 in campaign contributions. On May 2, 2006, Ney defeated him 68%–32%.[9] On the day of the election, Greg Giroux of Congressional Quarterly noted: "I'd be surprised if Harris got more than 20 or 25 percent. That would be a sign that there is a chunk of the Republican base that's disenchanted with the incumbent."[10] Commenting on his situation after the primary, Ney said "I have a healthy campaign account, in contrast to the Democratic Party, which is deeply divided and has a candidate with almost no campaign cash."[11]

Ney's opponent in the November general election was to be Zack Space, a Dover, Ohio lawyer and hotel developer. As of July 2006, Space was considered to be slightly ahead of Ney, with a large percentage of undecided voters. For the first three months of 2006, Ney blamed legal costs for causing his re-election campaign to spend more than it raised. For the April–June period, it was unusually intense campaigning in his rural district that caused the six-term incumbent to spend $52,675 more than donors gave him in the last three months, he said.[12]

On August 7, 2006, state senator Joy Padgett announced that Ney was withdrawing his candidacy in the 2006 election, and that Ney and House Majority Leader John Boehner had asked her to run in his place.[13] Later that day, Ney confirmed in an interview with the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review that he would not run for re-election to a seventh term, but intended to serve out his term until January 2007. About his future plans, Ney said "I have some options in the nongovernment sector."[14] The Washington Post'' reported that Boehner met with Ney in early August "to urge him to step aside, reminding him that with a son in college and a daughter nearing college age, he will need money. [...] If he lost his House seat for the party, Boehner is said to have cautioned, Ney could not expect a lucrative career on K Street to pay those tuition bills, along with the hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees piling up."[15] On August 14, 2006, Ney officially withdrew from the race.[16] Because that occurred before August 19 (80 or more days before the election), Ohio Revised Code 3513.312 applied: "the vacancy in the party nomination so created shall be filled by a special election". If Ney had waited until August 20, section 3513.31 of the Ohio Revised Code would have pertained: Ney's replacement in the November general election would be named by a district committee of the Ohio Republican party.

The special election was held on September 14, and was won by State Senator Joy Padgett with just under half of the fewer than 1600 votes cast.[17]

It is widely believed that Ney's delay in resigning cost Padgett any chance of keeping the seat in Republican hands, as she was routed by Space 62% to 38%.

Tenure

Ney's voting record was less fiscally conservative, and more protectionist, than the median amongst Republicans elected in 1994. He did not earn a rating in the 90s from the American Conservative Union until 2004. He was known for bucking his party's leadership on issues important to his mostly blue-collar district, such as championing the needs of the beleaguered steel industry. In 1999, he was a prominent part of the "Stand Up for Steel" campaign, which united the steel industry and steel unions in a fight against low-priced imports. In 2000, he was one of a handful of Republicans who backed an effort to block permanent normal trade status for China. In 2001, Ney was one of three Republicans to vote against the USA Patriot Act (the other two were Butch Otter of Idaho and Ron Paul of Texas). In late 2001, Ney introduced the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) for election reform.[18] In 2005, he voted against President Bush's Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) and against Republican budget cuts to Medicaid and after-school programs.

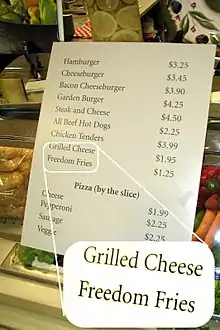

Freedom Fries

Ney also gained notoriety when he mandated, as Chairman of the House Administration Committee, that "French fries" be renamed "freedom fries" on House of Representatives food service menus, to indicate displeasure with France's lack of support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Ney led the effort, along with fellow Republican U.S. Congressman Walter B. Jones, to change the names of "French fries" and "French toast" to "freedom fries" and "freedom toast". His committee had authority over House cafeterias. Ney said at a press conference that "this action today is a small, but symbolic effort to show the strong displeasure of many on Capitol Hill with the actions of our so-called ally, France."[19] Ney did not comment about the opposition to the U.S. and British-led invasion and occupation coming from other nations such as Russia and Germany.[20] In July 2006, after Ney had left the committee, the names were changed back; Ney had no comment.[21]

Abramoff scandal timeline

- November 2005

Ney was subpoenaed in the investigation in November 2005. Michael Scanlon pleaded guilty to conspiring to bribe a member of Congress, identified as Ney, and other public officials. In the agreement, Scanlon admitted to bribing Ney in return for, among other things, the following (described in more detail below):

- Ney's placing statements in the Congressional Record relating to the SunCruz Casinos scandal;

- Ney's using his position to attempt to endorse and support a client of Abramoff's as a provider of a wireless telephone infrastructure to the House of Representatives;

- Ney's agreement to introduce and seek passage of legislation that would lift an existing federal ban against commercial gaming for two different Native American tribes in Texas (clients of Abramoff);

- Ney's agreement to assist legislation to financially benefit a California tribe.[22]

- January 2006

On January 3, 2006, Abramoff pleaded guilty to three felony counts involving charges stemming principally from his lobbying activities in Washington on behalf of Native American tribes.[23] One of the cases of bribery described in the plea agreement detail involves a person identified as "Representative #1". Ney's spokesman confirmed that Ney is Representative #1.[24]

A press release from the Department of Justice describes the particulars:

- Abramoff also admitted that as one means of accomplishing results for their clients, he, Scanlon, and others engaged in a pattern of corruptly providing things of value to public officials, including trips, campaign contributions, and meals and entertainment, with the intent to influence acts by the public officials that would benefit Abramoff and Abramoff’s clients. For example, Abramoff and Scanlon provided things of value to a public official (described as Representative #1) and members of his staff, including, but not limited to, a lavish trip to Scotland to play golf on world-famous courses, tickets to sporting events and other entertainment, regular meals at Abramoff’s upscale restaurant, and campaign contributions for the Representative, his political action committee, his campaign committee, and other political committees on behalf of the Representative. At the same time, and in exchange for these things of value, Scanlon and Abramoff sought and received the Representative’s agreement to perform directly and through others a series of official acts, including but not limited to agreements to support and pass legislation, and agreements to place statements in the Congressional Record.[25]

Ney said in a statement that "At the time I dealt with Jack Abramoff, I obviously did not know, and had no way of knowing, the self-serving and fraudulent nature of Abramoff's activities". Ney spokesman Brian Walsh said that any official actions Ney had taken were based on "the merits and facts of the situation and not because of any improper influence from Jack Abramoff or anybody else".[24]

On January 15, 2006, Ney resigned as chairman of the House Administration Committee. He maintained that he had done nothing wrong, but had been under increasing pressure to stand down since his ties to Abramoff were an increasing embarrassment in light of Republican plans for reforms of lobbying and campaign finance rules. The House Administration Committee has jurisdiction over elections and lobbyists. House Speaker Dennis Hastert reportedly emailed a Roll Call article regarding Ney's precarious hold on the gavel to several Capitol beat reporters. Ney's resignation was officially temporary. However, even some of his Republican colleagues expected him to be indicted. Under Republican caucus rules, he would have permanently lost his chairmanship if indicted.

Abramoff's plea agreement also details his practice of hiring former congressional staffers. Abramoff used these persons' influence to lobby their former Congressional employers, in violation of a one-year federal ban on such lobbying.[23][26] Named in the Department of Justice indictment are two Abramoff colleagues, "Staffer A" and "Staffer B", who are Tony Rudy and Ney's former chief of staff, Neil Volz (who left Ney's office to work as a lobbyist for Barnes & Thornburg) respectively.[27]

- May 2006

On May 8, 2006, Volz pleaded guilty to conspiring to corrupt public officials and violating lobbying rules. Bloomberg News described the plea agreement:

- In court documents filed as part of Volz's plea agreement, prosecutors said that he and others at Greenberg Traurig offered trips, tickets to sporting events and numerous meals at Abramoff's restaurants to Ney. In 2003, Volz paid for part of a two-night trip to the Sagamore Resort in Lake George, New York, for Ney and members of his staff, prosecutors said.

- Ney, for his part, agreed to help Abramoff clients with acts such as inserting language into legislation that would lift a gaming ban hurting one of the tribes, prosecutors said. The court documents also describe conversations in which Volz told Ney what Abramoff wanted him to say in meetings with the tribal client.[28]

On May 18, 2006, the House Ethics Committee announced an investigation into bribery allegations against Ney. Will Heaton, his chief of staff, was subpoenaed.[29]

- June 2006

The federal grand jury issued a subpoena to Matthew D. Parker, Ney's campaign manager.[30] On June 29, 2006, three of Ney's staffers resigned: Brian Walsh, a longtime Ney spokesman; Will Heaton, Ney’s chief of staff; and Chris Otillio, a senior legislative aide. In a statement, Ney said that Congressional staff turnover is high, and that all three departing staff members had worked for him longer than many others stay in similar jobs.[31]

- July 2006

John Bennett, a staffer in Ney's district office, received a subpoena.[32]

- September 2006

On September 15, 2006, the Justice Department filed Ney's guilty pleas to a charge of conspiracy to defraud the United States and to a charge of falsifying financial disclosure forms. Both charges are related to actions taken on behalf of Abramoff's clients in exchange for bribes, as well as separate actions taken on behalf of a foreign businessman in exchange for over $50,000 in gambling sprees at foreign private casinos.[33] In four separate guilty pleas, Jack Abramoff, former DeLay deputy chief of staff Tony Rudy, former DeLay press secretary Michael Scanlon and former Ney chief of staff Neil Volz all said Ney had used his position to grant favors to the Abramoff lobbying team in exchange for gifts, including a free trip to the Super Bowl, Northern Marianas Islands, Scotland, the use of luxury boxes at sporting events, and concerts and meals. Ney is the first member of Congress to admit to criminal charges in the Abramoff investigation, which has focused on the actions of several current and former Republican lawmakers who had been close to the former lobbyist.[34] Ney announced he was entering inpatient treatment for rehabilitation and was entering a guilty plea to federal corruption charges related to the Abramoff scandal. He admitted to making "serious mistakes" and stated that, after helping people for his entire political career, it was he who needed the help now.

- October 2006

On October 13, Ney officially pleaded guilty before U.S. District Court Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle. He issued a statement saying that he was "ashamed" that he had to end his career as a public servant in such a fashion.

Ney did not immediately resign from the House, even though under House rules he would not have been able to vote or participate in any committee work during the chamber's "lame duck" session in December. He claimed that he had outstanding work to finish in his congressional office. Also, several officials said that he was in severe financial straits and needed to continue drawing his congressional salary for as long as possible. The four highest-ranking members of the Republican House leadership—Hastert, Boehner, Majority Whip Roy Blunt and House Republican Conference Chairwoman Deborah Pryce—issued a joint statement demanding that Ney resign before the lame duck session. If he didn't do so, they said, they would make a resolution to expel him the first order of business at the lame duck session.[35]

On November 3, four days before the general election, Ney submitted his resignation to Hastert.[36]

William Heaton, Chief of Staff for to Rep. Bob Ney also pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit fraud.[37] admitting to conspiring with Ney, Jack Abramoff and others to accept vacations, meals, tickets, and contributions to Ney's campaign in exchange for Ney benefitting Abramoff's clients.(2006)[38]

SunCruz Casinos Scandal

Ney is also implicated in the separate Abramoff SunCruz Casinos scandal.[39] The conduct alleged is that Ney twice entered statements into the Congressional Record at Scanlon's request in exchange for a $10,000 contribution.

In March 2000, before a deal for Abramoff and others to purchase SunCruz was closed, Ney entered the following comments into the Congressional Record that were critical of the management of SunCruz: "Mr. Speaker, how SunCruz Casinos and Gus Boulis conduct themselves with regard to Florida laws is very unnerving. Florida authorities have repeatedly reprimanded SunCruz Casinos and its owner Gus Boulis for taking illegal bets, not paying their customers properly and had to take steps to prevent SunCruz from conducting operations altogether."[40][41] It is alleged that this statement was intended to pressure SunCruz to sell to Abramoff on terms favorable to the latter.

The second time was in October 2000. It is alleged that Ney, like other Republicans in the House, was under pressure to raise money for the Republican National Congressional Committee (RNCC) in October 2000, a month prior to the November elections. In an October 23 e-mail from Abramoff to Scanlon, Abramoff asked "Would 10K for NRCC from Suncruz for Ney help?"[42] Scanlon replied, "Yes, a lot! But would have to give them a definite answer—and they need it this week".

Indian gambling

Ney introduced legislation that would allow the Tiguas Indians to reopen their casino after receiving $32,000 in donations to his PAC and campaign from the tribe.

In March 2002, Abramoff e-mailed Marc Schwartz, a consultant for the Tiguas, instructing him to donate to Rep. Ney's campaign. The tribe donated $2,000 to the campaign and $30,000 to Ney's PAC. Scanlon e-mailed Abramoff on March 20, 2002 to tell him that he had signed up Rep. Bob Ney to attach a provision allowing the Tiguas to have gaming rights to the Help Americans Vote Act, which Ney had co-authored: "just met with Ney!!! We're f'ing gold!!!! He's going to do Tigua." (Former Ney Chief of Staff Neil Volz, now an Abramoff employee, made the appeal to Ney's staff while still subject to the one-year lobbying ban).[43]

According to testimony by Tigua representatives, Abramoff set up a lengthy meeting between tribal representatives and Ney in Ney's office in August 2002, as well as a conference call, and Ney assured them he was working to insert language that would reopen their casino into an unrelated election reform bill. Ney's attorney reported that he found a calendar reference indicating that Ney had had a meeting with the "Taqua".[44]

Ultimately, the Tiguas casino language did not become law. Abramoff, Scanlon, and Ney had promised the tribe that the provision would win Senate support from Senator Christopher Dodd. Dodd said that he never supported the amendment. The Tiguas then claimed they were defrauded—by Abramoff, Scanlon, and Ney.[43]

In November 2004, Ney told Senate investigators that "he was not at all familiar with the Tigua" and could not recall meeting with members of the tribe. Brian Walsh, a spokesman for Ney, said in June 2006 that the congressman's meeting with the committee "was a voluntary meeting—it was not conducted under oath".[44]

License to a telecommunications firm

Ney, as chairman of the House Administration Committee, approved a 2002 license for an Israeli telecommunications company to install equipment to improve cell phone reception in the Capitol and adjacent House office buildings, equipment that would generate significant revenue for the firm. The company, then Foxcom Wireless, an Israeli start-up telecommunications firm, (which has since moved headquarters from Jerusalem to Vienna, Va., and been renamed MobileAccess Networks) later paid Abramoff $280,000 for lobbying. It also donated $50,000 to Abramoff's Capital Athletic Foundation, a non-profit organization that Abramoff used to redistribute money for personal and political gain.

A spokesman for Ney claimed that wireless providers had voted for Foxcom in secret ballots, but spokesmen for each of the six wireless companies told The Washington Post they had remained neutral in the selection process. Ney refused to make public a copy of documents relating to the agreement.[45][46]

Involvement in U.S. sanctions on arms sales to Iran

In the late 1970s, Ney went to Iran to teach English. Since then, he has maintained an active interest in Iranian affairs and was the only member of Congress fluent in Persian.[47]

In January 2006, Newsweek reported that Ney's lawyer confirmed that federal prosecutors have subpoenaed records on an expenses paid February 2003 trip to London that Ney took along with former U.S. lobbyists, Roy Coffee and David DiStefano.[48] The trip was paid for by "Nigel Winfield, a thrice-convicted felon who ran a company in Cyprus called FN Aviation. Winfield was seeking to sell U.S.-made airplane spare parts to the Iranian government—a deal that would have needed special permits because of U.S. sanctions against Tehran", and that "Ney personally lobbied the then Secretary of State Colin Powell to relax U.S. sanctions on Iran."[49]

Syrian businessman Fouad al-Zayat, who was responsible for managing the transaction on behalf of the Iranian military, was also identified for bribing Ney for his lobbying efforts.[50][51][52]

Legal fees

A filing with Federal Election Commission in October said that Ney had paid the law firm Vinson & Elkins $136,000 from July through September, from campaign funds.[53][54] By early January 2006, the total legal expenses paid by Ney's political campaign committee had risen to $232,381.[12] For the January to March 2006 reporting period, Ney paid an additional $96,000 in legal fees from campaign funds to that law firm; total campaign spending for the period was $250,000.[55] The legal fees are related to an ongoing federal investigation (see below.)

Brian Walsh, spokesman for Ney, said in April 2006: "Frankly, it's an unfortunate commentary on the justice system that someone has to spend a lot of money simply to clear their name and set the record straight in what is in this case completely false allegations." He also said that "the congressman is doing everything possible and moving as quickly as possible to put these allegations to rest and clear his name."

In a Federal Elections Commission filing showing expenses through the end of June 2006, Ney reported that he had not paid any legal fees since January 5 from campaign funds. Mark Tuohey, the lead lawyer at Vinson & Elkins, said Ney "needs money for his campaign and that's a priority right now. He intends to pay. He'll pay his fees, I have no doubt about that."[12]

In November 2005, it was reported that Ney had set up a legal defense fund for himself in connection with the Abramoff case. Documents filed in the House in January 2006 showed that the Ethics Committee had approved the organization papers for the fund. The fund raised $40,000 between January and March 2006, and nothing between April and June 2006. The fund did not spend any money for Ney's legal expenses.[56][57] Ney's withdrawal from the race (see below) meant that he could use his remaining campaign funds (almost half a million dollars) for his legal defense.[58]

Post-congressional life

Resignation

On November 3, 2006, facing an impending expulsion vote, Ney resigned from the House of Representatives by his letter of resignation to Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert.[59][60]

Sentencing

On January 19, 2007, Ney was sentenced to a 30 months in prison, ordered to pay a $6,000 fine[61] and provide 200 hours of community service. On the orders of Judge Ellen Huvalle, Ney reported to Federal Correctional Institution, Morgantown in Morgantown, West Virginia on March 1, 2007. He shared a space in the prison with former Survivor star Richard Hatch, a Morgantown inmate serving 51 months for failing to pay taxes.[62]

After prison

He was released on August 15, 2008 after serving 17 months.[63] After his prison term Ney was required to be on probation for two years. An admitted alcoholic, the judge also barred him from drinking during his probation and to undergo counseling.[64]

In April 2009, Ney started the Bob Ney Radio Show, a talk show on West Virginia radio station WVLY (AM).[65]

In March 2013, Ney released his memoir, Sideswiped: Lessons Learned Courtesy of the Hit Men of Capitol Hill.[66][67][68]

Ney currently serves as political analyst for Talk Media News[69] and regularly appears remotely on the Thom Hartmann Program.[70]

Electoral history

| Year | Democrat | Votes | Pct | Republican | Votes | Pct | 3rd Party | Party | Votes | Pct | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Greg DiDonato | 87,926 | 46% | Robert W. Ney | 103,115 | 54% | ||||||||

| 1996 | Robert L. Burch | 108,332 | 46% | Robert W. Ney | 117,365 | 50% | Margaret Chitti | Natural Law | 8,146 | 3% | ||||

| 1998 | Robert L. Burch | 74,571 | 40% | Robert W. Ney | 113,119 | 60% | ||||||||

| 2000 | Marc D. Guthrie | 79,232 | 34% | Robert W. Ney | 152,325 | 64% | John R. Bargar, Sr. | Libertarian | 4,948 | 2% | ||||

| 2002 | (no candidate) | Robert W. Ney | 125,546 | 100% | ||||||||||

| 2004 | Brian R. Thomas | 90,820 | 34% | Robert W. Ney | 177,600 | 66% | ||||||||

| 2006 | Zack T. Space | 129,646 | 62% | Joy Padgett * | 79,259 | 38% |

*While Ney won the Republican primary in 2006, he withdrew on August 14, 2006 due to his legal problems. Padgett won the special primary that followed.

See also

Notes

- "On Capitol Hill, Ney Is the Mayor". The New York Times. November 19, 2005. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- "Our Campaigns - OH District 18 - R Primary Race - May 03, 1994".

- "Our Campaigns - OH District 18 Race - Nov 08, 1994".

- "Our Campaigns - OH District 18 Race - Nov 05, 1996".

- Hauser, Christine (January 25, 2006). "Congressman Tied to Lobbying Inquiry to Seek Re-election". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Nichols, John (August 7, 2006). "Culture of Corruption Claims Another Congressman". The Nation.

- Chalian, David (January 25, 2006). "Liberal Groups Start Campaigning Against 'Culture of Corruption'". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- Murray, Mark (March 7, 2006). "Will the 'culture of corruption' theme fly?". NBC News. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- "Our Campaigns - OH District 18 - R Primary Race - May 02, 2006".

- Rood, Justin (May 2, 2006). "Ney Primary: Watch the Protest Vote". TPM Muckraker. Archived from the original on May 27, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Marshall, Joshua Micah (May 3, 2006). "Rep. Bob Ney (R-OH) on what he and his party have to offer voters". Talking Points Memo. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Hammer, David (July 17, 2006). "Ohio congressman's legal payments on hold". Associated Press News. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- McCarthy, John. "Rep. Bob Ney drops re-election bid". The Mercury News. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- Heyl, Eric. "Ney drops out of fall race". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- Weisman, Jonathan. "Embattled Rep. Ney Won't Seek Reelection". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- "Ohio Rep. Ney Asks Off The Ballot". CBS News. August 14, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

- 2006 Election results

- "Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Loughlin, Sean (March 12, 2003). "House cafeterias change names for 'French' fries and 'French' toast: Move reflects anger over France's stance on Iraq". CNN. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- House cafeterias change names for 'French' fries and 'French' toast, CNN, Sean Loughlin, March 12, 2003. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Bellantoni, Christina (August 2, 2006). "Hill fries free to be French again". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Ex-DeLay Aide In Corruption Ple - November 21, 2005

- "Abramoff Lawsuit" (PDF). NPR. Retrieved 2006-01-03.

- Weisman, Jonathan (January 4, 2006). "GOP Leaders Seek Distance From Abramoff". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-01-04.

- #06-002: 01-03-06 Former Lobbyist Jack Abramoff Pleads Guilty to Charges Involving Corruption, Fraud Conspiracy, and Tax Evasion

- "Lobbyist case threatens Congress". BBC News. January 4, 2006. Retrieved 2006-01-04.

- Schor, Elana. "Abramoff will testify". The Hill. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved 2006-01-04.

- Jensen, Kristin (May 8, 2006). "Ney's Former Aide Volz Pleads Guilty in Abramoff Case". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- Congressional Record

- Eaton, Sabrina. "Ney aide subpoenaed in lobbying investigation". Cleveland Live. Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- Riskind, Jonathan; Jack Torry; James Nash (June 30, 2006). "Senior aide to Rep. Ney subpoenaed: Three staff members leaving while investigation continues". Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- "Another Ney aide subpoenaed in probe". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

- DOJ press release on Ney's plea Archived November 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Eaton, Sabrina. "Ney to plead to criminal charge". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Schmidt, Susan; Grimaldi, James V. (14 October 2006). "Ney Pleads Guilty to Corruption Charges". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "Scandal-tainted Ohio congressman resigns". CNN.com. Retrieved 2006-11-03.

- Jackie Kucinich; Susan Crabtree (February 27, 2007). "Ney's former chief of staff agrees to plead guilty".

- James V. Grimaldi; Carol D. Leonnig (February 27, 2007). "Former Aide to Ex-Congressman Ney Pleads Guilty in Abramoff Case". The Washington Post. p. A06.

- "CQ.com - MoneyLine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-01-10. Retrieved 2006-02-01.

- Schmidt, Susan; Grimaldi, James V. (2005-05-01). "Untangling a Lobbyist's Stake in a Casino Fleet". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- "Untangling a lobbyist's stake in a casino fleet". NBC News. May 2005. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- Zagorin, Adam; Calabresi, Massimo (2006-01-15). "Quid Pro Quo?: Jack Abramoff's $10,000 Question". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- Bonner, Austin. "The Muckraker's Reference Section: Bob Ney". TPM Muckraker. Archived from the original on 2006-04-20. Retrieved 2006-03-29.

- Schmidt, Susan. "Senators' Report On Abramoff Case Disputes Rep. Ney". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2006-06-23.

- Grimaldi, James. "Lawmaker's Abramoff Ties Investigated". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2005-10-18.

- Hearn, Josephine. "Pelosi Calls for Investigation into Ney Dealings with Wireless Firm". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 18, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- Shoup, Anna. "Bob Ney Background Report". PBS. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved 2006-11-06.

- "Ohio Rep. Bob Ney Admits Guilt in Corruption Probe". Fox News. 25 March 2015.

- Hosenball, Mark. "Lobbying: The Web Widens". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2006-01-17. Retrieved 2006-01-23.

- "Billionaire gambler sued by Iran in UK court". The Times.

- "The Fat Man's US gamble backfires". The Guardian. 4 March 2007.

- "'Fat Man' gambler who refused to honour £2m debt is told to pay up". Evening Standard. 13 April 2012.

- Bolton, Alexander (November 8, 2005). "Ney sets up defense fund on Abramoff". The Hill. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- Hammer, David (November 9, 2005). "Ohio Republican Ney forms legal fund". Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 27, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- "FILING FEC-213756, Form 3, Bob Ney For Congress". Federal Election Commission. April 20, 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Krawzak, Paul M. (August 1, 2006). "Ney report shows no money raised for legal defense fund". CantonRep.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- Eaton, Sabrina (May 3, 2006). "Ney backers raise $40,000 for his legal defense fund". The Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- "Editorial: Ney Bails Out". Toledo Blade. August 10, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- Hammer, David. "Rep. Ney of Ohio resigns from Congress". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- Gaudiano, Nicole (November 4, 2006). "Ohio's Ney resigns House seat". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-11-05.

- "Republican Ney sentenced to jail". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- "Ex-Rep. Ney Reports to Federal Prison". The Washington Post. March 1, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- Nash, James (August 16, 2008). "Ney freed after serving 17 months for corruption". The Columbus Dispatch.

- "Republican Ney sentenced to jail." BBC. Friday January 19, 2007. Retrieved on January 26, 2010.

- Thrush, Glenn (April 13, 2009). "Ex-jailbird Ney gets radio show". Politico.

- Gavin, Patrick (8 March 2013). "Ney: 'Sideswiped' isn't about revenge". POLITICO. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- Ney, Robert W. (2013). Sideswiped : Lessons Learned Courtesy of the Hit Men of Capitol Hill. BookBaby. ISBN 9780988247642. OCLC 898103883.

- Thom Hartmann Book Club - "Sideswiped" by Bob Ney - September 1, 2016, archived from the original on 2021-12-21, retrieved 2019-09-25

- "Our Team". Talk Media News. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Search Results: "Bob Ney"". Thom Hartmann - News & info from the #1 progressive radio show. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- "Election Statistics". Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 2007-12-26. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

External links

- United States Congress. "Bob Ney (id: N000081)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Associated Press profile

- List of campaign contributors to Bob Ney

- Operation Open Doors, The Washington Post editorial, December 3, 2004

- Congressman Linked to Abramoff Is No Stranger to Lobbyists, Los Angeles Times, January 22, 2006, by Noam N. Levey and Walter F. Roche Jr.

- House Ethics Panel, Justice Dept. to Run Parallel Probes, The Washington Post, May 19, 2006, by Jeffrey H. Birnbaum

- "The 13 Most Corrupt Members of Congress"—Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington

- Voting record maintained by the Washington Post

- Plea Agreement, US District Court of D.C., signed September 15, 2006

- Criminal Information to the Plea, US District Court of D.C., signed September 15, 2006

- Factual Basis to the Plea, US District Court of D.C., signed September 13, 2006

- List of candidates for the Eighteenth Congressional District of Ohio Archived 2007-01-02 at the Wayback Machine