Robert Roddam

Robert Roddam (1719 – 31 March 1808) was an officer of the Royal Navy who saw service during the War of the Austrian Succession, the Seven Years' War, and the American War of Independence. He survived to see the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, but was not actively employed during them.

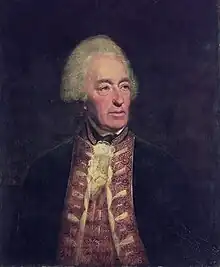

Robert Roddam | |

|---|---|

Roddam c. 1783 | |

| Born | 1719 Roddam Hall, Northumberland |

| Died | 31 March 1808 (aged 88–89) Morpeth, Northumberland |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Great Britain United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Service/ | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1735 – 1808 |

| Rank | Admiral of the Red |

| Commands held | HMS Viper HMS Greyhound HMS Bristol HMS Greenwich HMS Colchester HMS Lenox HMS Cornwall Nore Command Portsmouth Command |

| Battles/wars | |

Robert Roddam was born to a gentry family in northern England, and entered the navy some years before the outbreak of the War of Jenkins' Ear. He worked his way up through the ranks during this war, and the wider War of the Austrian Succession, distinguishing himself in several actions and gaining promotions which eventually led to his first command in 1746. He impressed his superior officers, including George Anson and Sir Peter Warren, with his ability and enthusiasm, particularly during a daring attack on a French force at Cedeira . Appointed to larger and more powerful ships, Roddam continued to win praise, and spent some time in North American waters, where he became embroiled in local power struggles. Sent to the Caribbean shortly after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, Roddam encountered a powerful French squadron, and after a hard-fought struggle, was captured and taken prisoner. Released after a period of time spent imprisoned in poor conditions, Roddam was tried by court martial and honourably acquitted.

He spent some time with the Channel Fleet watching the French coast, and was briefly employed as senior officer of one of the blockading squadrons, where he again showed his willingness to fight against heavy odds. He was employed briefly escorting convoys before the end of the war, after which he went ashore. Returning to active service during the Falklands Crisis in 1770, he commanded ships until 1773, and was again recalled to active service, this time with the outbreak of the American War of Independence. He was promoted to flag rank not long afterwards, and became commander-in-chief at the Nore. His final period of active service came during the Spanish armament of 1790, when he was commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, and readied ships for the anticipated war with Spain. He continued to be promoted, reaching the rank of admiral of the red in 1805. He inherited the family seat at Roddam Hall, but though he married three times, he died without issue in 1808.

Family and early life

Robert Roddam was born in 1719 at the family seat of Roddam Hall, in Northumberland. He was the second of three sons born to Edward Roddam, and his wife, Jane.[1] Roddam entered the navy in 1735, joining the 20-gun HMS Lowestoffe as a midshipman under Captain Drummond, with whom he served in the West Indies for the next five years.[1][2] He then transferred in succession to the 80-gun ships HMS Russell, HMS Cumberland and HMS Boyne

During this time, he served with Sir Chaloner Ogle and Sir Edward Vernon at the Battle of Cartagena de Indias, and the occupation of Cumberland Bay in 1741.[1][2] He distinguished himself during these encounters, and narrowly escaped being killed, when a cannonball shot off part of his coat.[2] He was promoted to third lieutenant of the 60-gun HMS Superb on 2 November 1741, and served under her commander, Captain William Hervey.[1][2] Roddam was present when Superb encountered a Spanish ship off the Irish coast during her voyage back to Britain. The Spanish ship, measuring 400 tons, was armed with 20 guns and manned by a crew of 60, was captured, and later valued at £200,000.[3]

Hervey's court martial

Hervey had gained a reputation for ill treatment of his officers, and on Superb's return to Plymouth in August 1742, Hervey was tried by court martial on charges of 'cruelty, ill usage of his officers, and neglect of duty'.[1][a] In response, Hervey made accusations against his first lieutenant, John Hardy, who was also brought to court martial.[4] Roddam gave evidence to support the charges against Hervey, who was found guilty and cashiered, while Hardy was honourably acquitted.[1][4]

Monmouth and 'witchcraft'

With Superb paid off at Plymouth, Roddam was appointed third lieutenant of the 64-gun HMS Monmouth on 7 September 1742, serving under Captain Charles Wyndham.[1][2] He was with Monmouth for the next four years, spent cruising off the French coast, and travelling as far south as the Canary Islands.[1] While off Tenerife at midnight one day, Roddam, as master of the watch, was ordered to put the ship about. Three times he attempted it, but each time it proved impossible to do so, though there was no apparent obstacle to the manoeuvre.[5] When relieved by Lieutenant Hamilton, Roddam related the strange behaviour of the ship, suggesting that some sort of witchcraft was responsible. In Hamilton's presence, Roddam attempted to repeat the procedure, and for the fourth time the ship missed stays. At daybreak a strange sail was sighted ahead of Monmouth, which was chased down and captured. She proved to be a Spanish ship, valued at £100,000, which would otherwise have been missed had Monmouth come about during the night. Roddam was advanced to second lieutenant on 14 July 1744, during the captaincy of Henry Harrison, and two years later, on 7 June 1746, was promoted to his first command, that of the 14-gun sloop HMS Viper, which was nearing completion at Poole.[1][5]

First commands

Viper was launched at Poole on 11 June, and having got her ready for sea, Roddam sailed to join the Channel Fleet at Spithead, arriving on 26 July.[1][6] Shortly after his arrival, the commander-in-chief, George Anson expressed a desire to stop a fleet, then at Plymouth, from sailing. The commanders of the various ships in the fleet argued against sending a ship, owing to the strong south-westerly wind, but Roddam, despite having a brand-new ship, not fully fitted and trialled at sea, offered to make the attempt. Impressed, Anson wrote to the Admiralty, and requested that Roddam be placed under his command.[6]

Anson was later superseded by Vice-Admiral Sir Peter Warren, who in mid-1747 received word from a Bristol-based privateer that a fleet of some 30 ships were assembled at Cedeiro Bay, near Cape Ortegal, loaded with naval stores. The entrance to the anchorage was very narrow, and was defended by two shore batteries. With the odds against any attack, Sir Peter decided that there was little point in risking an assault.[6]

At this time Captain Henry Harrison, Roddam's old commander on Monmouth, suggested to Warren that Roddam make an attempt in Viper, adding that 'He would answer for that young man effecting all that human nature could perform'.[7]

Impressed with Harrison's confidence, Warren ordered Roddam to make an attack. Roddam sailed that evening, and was in position the following morning. He stormed the first battery, carrying it and destroying all its guns, as well as capturing a Spanish privateer which emerged from the bay. He then entered the bay, burnt twenty-eight merchant ships and captured five of them, the most he could provide sailors to man from his small crew.[1][7]

The inhabitants of the town of Cedeira offered to surrender to Roddam on his terms, but were told that Roddam 'did not come there to aggrandize himself or crew by distressing harmless individuals, but only such as armed against Great Britain...'[7]

On his return to England Roddam was embraced by Warren, who thanked him personally for his skill and gallantry. Warren wrote to the Admiralty strongly recommending Roddam for promotion, and as a result of his efforts, Roddam was advanced to post captain on 9 July 1747, and given command of the 24-gun HMS Greyhound.[1][7]

Meanwhile, Roddam had, on his return to Britain after his action off Cedeira, been petitioned by the constituents of Portsmouth to represent them as their Member of Parliament. Roddam turned down their offer, and went on to serve at sea under Commodore Mitchell, cruising off the Dutch coast and in the North Sea.[1][8] During this time he escorted Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, who was on a diplomatic mission to the Dutch Republic. Roddam's time in the North Sea came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which brought the War of the Austrian Succession to a close.[1][8]

He retained command of Greyhound and went out to North America to serve under Admiral Charles Watson at Louisbourg, who based Roddam at New York for the next three years until 1751.[1][8] While at New York in 1750, one of Greyhound's lieutenants accidentally shot a woman. A civil trial and court martial resulted, causing Roddam considerable trouble, and hinting at an anti-English mood among some sections of colonial society.[1][b]

Roddam was appointed to command the 50-gun HMS Bristol, which was then the Plymouth guardship, on 30 January 1753. He was moved to the 50-gun HMS Greenwich in 1755.[1][8]

Seven Years' War

Defending Greenwich

Roddam was ordered to the Caribbean shortly after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War and departed for Jamaica on 23 January 1757.[1] While cruising off Cape Cabron, San Domingo on 18 March 1757, mysterious sails were sighted, which were at first assumed to be a small fleet of merchant ships being conveyed by two frigates. They were in fact a squadron of French warships under Joseph de Bauffremont, consisting of the 84-gun Tonnant, the 74-gun ships Diadème and Desauncene, the 64-gun ships Éveillé and Inflexible, the frigates Sauvage and Brune, and a 20-gun storeship.[8] The French were to windward, and Bauffremont, unsure of Greenwich's identity, sent one of his frigates to examine her. Realising that with the wind in the Frenchman's favour, he could not escape, Roddam attempted to lure the frigate towards him, hoping to capture her before the rest of the fleet could intervene, and then send her immediately to Rear-Admiral George Townshend, the commander at Jamaica, with news of the French movements.[9]

On assessing Greenwich's strength, the frigate kept close to the squadron, which then came up and attacked, action commencing at 9 a.m. when Diadème opened fire. For the next twelve hours Greenwich was constantly engaged with one or other of the French ships.[9] Roddam still hoped to carry his plan of capturing one of them into execution, and assembled his men in an attempt to board the 64-gun Éveillé, but several of her consorts bore up and opened fire, damaging Greenwich's rigging and leaving her unmanageable. Roddam gathered his officers together, and told them that though they had no hope of winning against such a superior force, if any man could point out the admiral's flagship, he hoped to engage her and fight on for another hour or two.[9] His officers, among whom was Lieutenant James Wallace, pledged to follow their captain, but pointed out that they had done all in their power to defend their ship. At 9.30 p.m., Roddam agreed to surrender his ship, as further resistance would only cause further casualties among his men.[10]

The colours were then struck to Éveillé, upon which her commander demanded Roddam come aboard his ship.[10] Roddam refused, answering that if he was wanted on the French ship, a boat must be sent for him, or else he would rehoist the colours and defend the ship until she sank.[11] A lieutenant was then sent over in a boat from the French ship, and Roddam came aboard. The French commander, Captain Merville, gave Roddam the bedding of the ordinary ship's company and a dirty rug, and did not allow him to change his clothes.[11] Greenwich was ransacked, and the crew left unfed. Roddam protested, and demanded to be taken to see Bauffremont. After Roddam had expressed his grievances, Bauffremont asked Roddam why he had refused to come to present his surrender in his own boat. Roddam replied that he would have considered it a disgrace, and that his sword would have been delivered through the body of the person demanding it, had it happened to him.[12]

Captivity

Roddam and his men were taken to Hispaniola and imprisoned there. At first Roddam was allowed to visit his men everyday, but after some time, this was refused. His men became concerned that he had been murdered, and on not getting a satisfactory answer to their queries, seized their guards and took up arms.[13] The prison governor sent for Roddam and asked him to restore order among his men, which Roddam only agreed to do once he had received promises of better treatment for them. Their treatment improved, and after two months in prison the men were paroled back to Jamaica.[13]

Court martial

On arriving back at Jamaica Roddam was tried by court martial for the loss of his ship. The court martial was held aboard HMS Marlborough on 14 July 1757.[10] After hearing evidence from the crew, the court honourably acquitted him, and Roddam had the minutes printed at Kingston for circulation.[1] He had hoped for similar success to the minutes printed from Admiral Sir John Byng's court martial, which had been held earlier that year, but found they did not sell as well as he had expected. He was told by the printer that 'if you had been condemned to be shot, your trial would have sold as well; but the public take no interest in an honourable acquittal'.[1]

Return to service

Roddam returned to England aboard a packet, and had to work to save the ship when the master pressed on too much sail in a gale, and again when a mysterious sail appeared to be attempting to catch the packet.[14] Roddam was exchanged shortly after his arrival in England, and went out as a passenger aboard HMS Montagu to join the fleet off Ushant under Sir Edward Hawke.[14] Hawke gave him command of the 50-gun HMS Colchester on 7 December 1759.[1][14] After taking her to Plymouth to fit her out, he was sent by Hawke to cruise off Brest, watching the French fleet there in company with HMS Monmouth, under Captain Augustus Hervey, and HMS Montagu under Captain Joshua Rowley.[14] Three French warships came out, which the British ships chased back under the guns of the shore batteries, and ran one of them ashore.[14]

Off Belle Île

Having carried this out, Roddam was sent to relieve Robert Duff, who was cruising off Belle Île. To do so he sailed Colchester through Le Ras, a narrow channel separating the Saints from the mainland, and entered Audierne Bay, and became the first known English ship to do so.[15] On arriving he received orders to watch a fleet of transport ships, with an escort of 16 frigates, moored there, believed to be preparing to carry troops to invade Ireland. Lacking sufficient ships to engage the frigates, Roddam gave orders that if possible the French were to be engaged so as to target the transport ships and shoot away their masts, but to avoid the frigates.[15] When questioned by his subordinates that ordering his ships not to engage would leave them open to accusations of cowardice, Roddam replied that since he gave the order, only he could be accused, and he would take Colchester and engage all the frigates single-handedly, trusting that 'some of them would be sent to the bottom.'[15]

_-_Captain_John_Reynolds_(c.1713%E2%80%931788)_-_BHC2963_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich.jpg.webp)

Before long Commodore John Reynolds arrived aboard HMS Firm and superseded Roddam as senior officer. Reynolds assessed the possibility of attacking the convoy lying in the river, but was advised by his captains that it could not be done. Roddam requested permission to try anyway, as Colchester was 'an old man of war, not worth much, and the loss of her would be trifling for the good of the service.'[16] Reynolds forbade Roddam from trying, whereupon Roddam suggested that Reynolds cruise off one of the channels of Belle Île, while Roddam covered the other. Reynolds agreed to this, but that night the French were able to elude Reynolds, and escaped into the river Vans.[16] On Duff's return aboard HMS Rochester to resume command of the squadron, and finding Colchester in need of repairs, Roddam was sent back to Plymouth, to refit and re-provision.[16]

Convoy work

Roddam returned to Plymouth, with Colchester leaking badly, but the port admiral, Commodore Hanaway, merely sent some caulkers on board, and sent her back to sea to join Sir Edward Hawke off Vans with a convoy. On joining the fleet, Hawke asked who had sent him a ship in such poor condition, and sent Roddam back to Plymouth to properly refit.[17] Roddam was then sent to Saint Helena, with Captain Jeekill's 60-gun HMS Rippon under his orders, to bring home the East Indies convoy. They were joined for their return voyage by Sir George Pocock's squadron.[17] As the squadron and the convoy passed the Isles of Scilly, Roddam became concerned that they were too close to the land, and gave the signal to tack. Roddam had a second occasion to warn the convoy, when off Dover. Pocock gave the order to lie-to, but Roddam, seeing that some of the convoy were in danger of running onto South Foreland, signalled for the ships to bear away to the Downs.[17] In both instances Pocock deferred to Roddam's judgement, and thanked him for his efforts.[17] Colchester was then ordered to Portsmouth, and on peace being declared, went ashore.[18]

Falklands crisis and American War of Independence

Roddam was recalled to active service during the Falklands Crisis in 1770, with an appointment to command the 74-gun HMS Lenox on 7 December. The crisis died down without breaking into open conflict, and Roddam remained in command of Lenox, which was used as the Portsmouth guardship, until 19 December 1773, when he was relieved by Captain Matthew Moor.[1][18] With the outbreak of the American War of Independence Roddam again returned to active service, taking command of the 74-gun HMS Cornwall at Chatham on 17 March 1777, and took her to Spithead.[1][18] Here he was to command her as one of 12 ships sent to the Mediterranean, but he received his promotion to rear-admiral of the white on 23 January 1778 and was succeeded as captain of Cornwall by Captain Timothy Edwards.[1][18]

Roddam then became Commander-in-Chief, The Nore in 1778. He held the command for the remainder of the war, being promoted to vice-admiral of the blue on 19 March 1779 and vice-admiral of the white on 26 September 1780.[1][19] He was without active employment for a time after the end of the war, but was promoted to vice-admiral of the red on 24 September 1787, and on 20 April 1789 he became Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth.[1][19]

Later years

He was commander there for three years, flying his flag aboard the 84-gun HMS Royal William during the Spanish armament in 1790. During the crisis he received orders from the Admiralty to prepare the guardships for sea. He had them fitted and ready for manning within five days, and on being ordered to fit a further five ships for sea, completed the task in fourteen days.[19] His rapid response attracted French attention, who reported in their newspapers that 'British ships of war [have] sprung up complete like mushrooms.'[19] With the passing of the crisis Roddam struck his flag in 1792. With the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars Roddam received a promotion to admiral of the blue on 1 February 1793. He was promoted to admiral of the white on 12 April 1794, and admiral of the red on 9 November 1805.[1][19]

Family and personal life

Roddam married three times in his life. His first marriage was to Lucy Mary Clinton, the daughter of George Clinton, the governor of New York at the time of Roddam's posting there, on 24 April 1749. Lucy died on 9 December 1750.[1] He then married Alithea Calder, the daughter of Sir James Calder, 3rd Baronet, and a sister of Robert Calder, who would become an admiral in the wars with France, in March 1775.[1] Alithea died on 21 July 1799, with Roddam marrying a third time, this time to Ann, daughter of Elizabeth Harrison of Killingworth, Northumberland.[20] None of Roddam's marriages produced any children, and he left his estates to his distant relative William Spencer Stanhope, of Cannon Hall near Barnsley in south Yorkshire, the great-grandson of his first cousin Mary Roddam, wife of Edward Collingwood, and cousin to Admiral Lord Collingwood.[1] Robert Roddam had succeeded to the family estates in 1776, on the death without issue of his elder brother Edward Roddam, and settled at the family seat of Roddam Hall in Northumberland where he had been born.[1][21] He appears to have spent his time improving the house and grounds, and was probably responsible for adding the late eighteenth-century wings to the hall.[1] He also planted an avenue of trees, which are still extant today, named on Ordnance Survey maps as Admiral's Avenue, which leads to Boat Wood.[1]

Admiral Robert Roddam died at Morpeth on 31 March 1808.[1] His biographer, P. K. Crimmin, described him as a 'brave and competent sailor and a diligent administrator', but noted that he was 'not interested in politics or in a political route to professional advancement.'[1] Certain incidents during his career hinted to Crimmin of a 'certain naïvety towards the non-naval world', and he noted that Roddam's 'closest connections and friendships were service ones.'[1]

Roddam was buried in the Roddam Mausoleum in the churchyard of St Michael's, Ilderton, in north Northumberland.

Notes

a. ^ Hervey's actions in the Caribbean had, as early as October 1740, led the port admiral to recommend that he be relieved of command, but the Admiralty declined to act.[22]

b. ^ The controversy eventually involved a number of colonial leaders, including Chief Justice James DeLancey, Governor George Clinton, who was also Roddam's father-in-law, and John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, the Secretary of State for the Southern Department. Part of the debate revolved around the rights of the civil authorities to intervene in the military's judicial process, with Clinton criticising DeLancey's attempts to extend his authority at the expense of military discipline.[23]

c. ^ Greenwich enjoyed only a brief career with the French. She was taken into their service under Captain Foucault, and saw action with Guy François de Coetnempren, comte de Kersaint's squadron at the indecisive Battle of Cap-Français on 21 October 1757.[24] She survived the action and escorted a convoy to France, but was wrecked in a gale as she neared the French coast on 1 January 1758.[24]

Citations

- Crimmin, P. K. (2004). "Roddam, Robert (1719–1808)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23930. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Public Characters. p. 132.

- Schomberg. Naval Chronology. p. 180.

- Beatson. Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain. p. 161.

- Public Characters. p. 133.

- Public Characters. p. 134.

- Public Characters. p. 135.

- Public Characters. p. 136.

- Public Characters. p. 137.

- Public Characters. p. 138.

- Public Characters. p. 139.

- Public Characters. p. 140.

- Public Characters. p. 141.

- Public Characters. p. 143.

- Public Characters. p. 144.

- Public Characters. p. 145.

- Public Characters. p. 146.

- Public Characters. p. 147.

- Public Characters. p. 148.

- Will, Elizabeth Harrison of Killingworth. 1799/1803: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-XCT9-L2B

- Burke. Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History. p. 1134.

- Hill & Ranft. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. p. 144.

- Brodhead, Fernow & O'Callaghan. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. pp. 571–6.

- Marley. Wars of the Americas. pp. 280–1.

References

- Public Characters [Formerly British public characters] of 1798-9 - 1809-10. London: H. Colburn. 1803.

- Beatson, Robert (1804). Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783. Vol. 1. London: Richard Phillips.

- Brodhead, John R.; Fernow, Berthold; O'Callaghan, Edmund B. (1855). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Vol. 6. Weed, Parsons.

- Burke, John (1847). Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry. Vol. 2. London: H. Colburn.

- Crimmin, P. K. (2004). "'Roddam, Robert (1719–1808)'". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23930. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hill, J. R.; Ranft, Bryan (2002). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860527-7.

- Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Schomberg, Isaac (1815). Naval chronology: or An historical summary of naval and maritime events... From the time of the Romans, to the treaty of peace of Amiens. Vol. 1. T. Egerton by C. Roworth.