Rochester and State Line Railroad

The Rochester and State Line Railroad was a 19th-century railroad company in New York state.

Background

In the middle of the 19th century, Rochester, New York's need for transportation[note 1] had not adequately been met by either the Genesee Valley Canal or the small local railroads that had been combined into the two major companies: the New York Central, with the Tonawanda, the Attica and Buffalo, and the Auburn and Rochester, and the Erie, with the Cohocton Valley and the Rochester and Genesee Valley[1] lines.

The purpose of the new railroad sought by the Rochester industrial and commercial interests was plain - the provision of cheap and reliable transport of Pennsylvania coal to the city of Rochester. During the mid-1860s, the price of coal in Rochester had tripled.[2] However, since the financial support of the outlying farm and commercial interests was vital to the project, in one of the lesser deceptions of the railroad building era, it was intimated to the public in the towns and villages of the Genesee Valley that the road would be built through western New York to carry agricultural products to city markets. While Rochester came up with $600,000 utilizing municipal bonds, rural communities raised nearly as much on their own.

The organization of the new rail line, the Rochester and State Line Railroad, occurred on 8 April 1869.

Purpose

Energy for the industry in Western New York at this time came from Pennsylvania coal, and the existing railroads were the sole means of getting it to the Rochester area. The railroads knew this, and their pricing reflected it. In 1863, a ton of coal cost approximately six dollars. Two years later, it was seventeen dollars. Talk of conspiracies between the coal and the railroad companies and calls for a new railroad generated ample enthusiasm. For some ten years, coal customers, and others, from Rochester and villages as far south as the Pennsylvania line sought to raise interest in a new railroad to the level at which something could be accomplished.

Genesis

Numerous meetings in Rochester and the outlying southern areas led to many proposals, at least one of which came to fruition. Oliver Allen II[note 2] and Donald McNaughton, both of Mumford, as well as Rochester attorney, D D S Brown, led a group of both business and government officials in promoting the project. In 1869, the Rochester and State Line Railroad was incorporated and chartered on 6 October to construct a railroad from Rochester to the Pennsylvania state line.[note 3] Allen was elected vice president of the new company. In the same year, the first surveys were done by William Wallace, who had done the same for the Scottsville and LeRoy Railroad thirty-five years earlier.

George Slocum writes in 1906:[3]

"The Rochester and State Line Railroad in its inception was a Wheatland institution. At one period in its early history, its officers, the President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, and four of the nine directors, were residents of Wheatland.

D. D. S. Brown, Oliver Allen, and Donald McNaughton were active and energetic in pushing this enterprise.

This road was opened for business from Rochester to Le Roy in 1874, to Salamanca in 1878, and completed to Pittsburg at a later date. In 1872 the town of Wheatland issued its bonds to the amount of $70,000.00 to aid in its construction, $53,000.00 of which has been paid. In 1860 the control of this road passed from the hands of those who had managed it, and its name was changed to the Rochester and Pittsburg R. R. Company. Later on, it was again changed to the Buffalo, Rochester, and Pittsburg R. R. Co. which name it now bears."

Although the initial state charter set the southern terminus at Wellsville, new coalfield discoveries in Pennsylvania spurred the organizers to move the route west, running through Warsaw and Ellicottville to Salamanca. This would facilitate an easier connection in Carrollton to the Buffalo, Bradford and Pittsburgh Railroad, and thus the coalfields of northern Pennsylvania.

The anxiety with which small communities (in the days before a reliable highway network) sought rail connections may be inferred from the actions of Perry. Upon learning of the R&SL plans not to connect with their village, local interests on 1 October 1868 set up their own railroad company[note 4] for a line from Perry to East Gainesville,[note 5] where the Erie Railroad had a station. When the R&SL was set up, Perry was on the route. However, when the route was shifted westward, Perry was off the route. Since interests along the original eastern route were now irate, yet another line, the Rochester and Pine Creek Railroad, was proposed to run from Caledonia to Castile through Perry. Perry was unimpressed and decided to maintain their original intention. Barely a few years later, the Silver Lake Railroad merged into the Rochester and Pine Creek and, on 1 February 1872, opened a short line between East Gainesville and Perry. Five years later, this company renamed itself the Silver Lake Railway.

A lamb between the wolves

In the middle of the 19th century, two interests essentially divided up the rail industry in New York State. Vanderbilt and the New York Central and Hudson River contended, often in dramatic terms, against Fisk, Gould, and Drew's Erie Railroad. The tie between the New York Central and the R&SL can be inferred from the presence of George J Whitney[4] on the boards of both companies. Vanderbilt had reason to want railroad access to the rich coal resources of Pennsylvania and to acquire the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad, which had a terminus at Salamanca. In 1872, Whitney started a two-year term as president of the RS&L, strengthening the unwritten alliance with Vanderbilt.

Construction

Schmidt says of the line (referring to Scottsville):[5]

"Soon after the war, promoters proposed a railroad to extend south of Rochester to the coal fields in Pennsylvania. In 1872 the town of Wheatland issued bonds for $70,000.00 to aid in its construction. D. D. S. Brown, Oliver Allen, and Donald McNaughton were again active in promoting the railroad. Mr. Allen was vice-president from 1869 to 1876, when he was elected president, and served in that capacity until the reorganization in 1880.

Work on the railroad was begun in 1873 and progressed rapidly since there were no great engineering difficulties to overcome until the foothills of the Alleghany Mountains near Warsaw were reached. Despite the financial panic of 1873 the Rochester and State Line Railroad was opened from Rochester to LeRoy in 1874. Little work was done for the next two years because railroad bonds and stocks were unsalable at any price. But as industry revived and railroads were showing increased earnings, work was resumed in 1876 and the railroad was completed to Salamanca in 1878. On May 15th there was a big excursion to Salamanca and large crowds attended the festivities. Ten years of work saw the completion of the railroad. The board of directors had labored faithfully and given their time and money, and this was to be their only reward.

The first locomotive[note 6] was built by Brooks of Dunkirk, N. Y., it was named "Oliver Allen" after the man who had worked zealously in the interest of the railroad.

In 1874 the rolling stock consisted of one engine and a boxcar to operate. When necessary, chairs were placed in the boxcar for passengers. Cars were often borrowed from other railroads. At one time when the railroad was being sued, all the real property the sheriff could obtain was the engine, which he locked up with chains.

Many miles of the State Line Railroad bed was built with gravel from the old John C. McVean farm. The farm at that time extended west of the railroad between North Road and Scottsville-Chili Road. After the cars began operating from Rochester to LeRoy, the mail, which had previously been taken to the Erie Railroad station in Rush, was carried by the Rochester and State Line Railroad. A new street, Maple Street, was opened up from Browns Avenue to the station to make the station more accessible to the village. The old station was located about three hundred feet north of the present one."

In the fine tradition of economizing on capital investment, the R&SL chose to use existing railbeds wherever practicable, such as the never-built Cattaraugus Railroad between Machias and Salamanca. In any event, the route layout was done by mid-1872.

The official start occurred on 21 August 1872. As Allen was the driving force,[note 7] he did the first-shovel thing in Mumford. Actual construction work began in 1873 (some sources say 1874). A year later, most of the route grading had been done.

Up to the summer of 1873, work progressed rapidly, with the bed ready for rail-laying by mid-May, but the Panic of 1873[note 8] brought the suspension of work on the line until the corporation's directors were able to arrange with Waterman & Beaver of Philadelphia for enough iron rails to complete the line from Rochester to LeRoy. Rails at that time, were selling for $88.00 a ton. 7 October 1873 saw the first rail spiked to the cross-ties in a ceremony at Lincoln Park, the line reaching Scottsville by November, Garbuttsville shortly thereafter, and Le Roy by year's end. The Rochester to Le Roy segment of the road was opened in May 1874.

On 15 September 1874, the first regular train on the Rochester and State Line Railroad reached Le Roy. Unfortunately, little or no work was done in the following two years, as the company's financial resources had been exhausted. By the end of 1876, the railroad line had been taken as far as Pearl Creek.[note 9] In June 1877, the line reached Warsaw.[note 10]

In an early example of the appropriately-named fast-track construction technique, a second crew built the southern part of the road, south out of Machias to Salamanca and north to the line built by the first crew. The south-bound work from Machias reached Salamanca on 28 January 1878; on 9 January, the line north from Machias and south from Rochester met in the town of Eagle. Now a respectable 108 miles long, the Rochester and State Line Railroad began revenue service along its full length on 16 May 1878.

The cowboy atmosphere of 19th-century railroading was reflected in an incident involving the Erie Railroad. When the RS&L construction crew needed to cross Erie's tracks in Le Roy, they simply built a level junction and kept going. The Erie took exception to this and tore up the crossing. While cooler heads prevailed in May 1877, the construction crew cared little, as they were already south of Erie's line.

The end of 1876 took the line as far as Pearl Creek, with Warsaw reached in June 1877. Completion occurred in very early 1878. The Salamanca Republican wrote:

"It is with feelings of no little gratification that we are enabled to announce that the last rail of the Rochester and State Line Railway has been laid and that another important artery of trade and commerce has been completed through Cattaraugus county. On Saturday last (January 26), the tracklayers on the R.&S.L. came in sight east of the village. By nightfall, the track was laid to within 80 rods of the Main street crossing. Work was continued Sunday and the gap was filled except with 10-12 rods. Monday forenoon it was rumored about town that the company officers were on their way over the road on a tour of inspection and would arrive at Salamanca in the afternoon. An informal meeting of citizens was held at Ansley & Vreeland's office and it was resolved that an impromptu reception should be given them . . . At 4:30, a volley from the brass six-pounder announced that the first railroad train from Rochester to Salamanca was in sight. Before the echoes of the gun died away the shrill whistles of a dozen locomotives raised such a din as was never before heard in Salamanca . . . The railroad party was then invited to the Krieger House where an impromptu entertainment had been prepared."

After all the finishing touches were applied, the official opening of the full line occurred on 16 May 1878.

The northern terminus of the route was Lincoln Park,[6][7] in southwest Rochester. It has a rail yard and junction and has figured prominently in the area's rail history.

Operation

- Images of the Rochester and State Line Railroad (click on image to enlarge)

Locomotive number 1

Locomotive number 1 Locomotive headlight

Locomotive headlight Ticket to ride

Ticket to ride Oil tank train at the Salamanca station

Oil tank train at the Salamanca station Named after Rochester's first mayor, the Rochester and State Line locomotive, "J E Child"

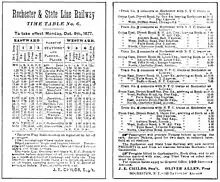

Named after Rochester's first mayor, the Rochester and State Line locomotive, "J E Child" Rochester and State Line Railway timetable of 8 October 1877. The name, J E Child, sometimes appears as J E Childs.

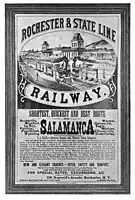

Rochester and State Line Railway timetable of 8 October 1877. The name, J E Child, sometimes appears as J E Childs. Rochester and State Line Railway advertising poster, circa 1878

Rochester and State Line Railway advertising poster, circa 1878 Rochester and State Line Railway first route map, circa 1878

Rochester and State Line Railway first route map, circa 1878

In 1874, the Rochester and State Line Railroad connected Rochester and Le Roy, although little traffic came to or from many small agricultural and industrial villages, thanks to the Great Depression of 1873–1879. Near the end of the depression, in 1878, the railroad had reached Salamanca, but the return to prosperity eluded many.

The freight carried by the new line varied. Initially, farm produce and lumber comprised the revenue loads, and this did not materially change until the line reached Salamanca. Then, crude oil became the dominant load, with solid trains of tankers running north to Rochester. In the end, it did not carry significant quantities of coal, resulting in its economic failure when the oil business declined.

Unlike the standardization prevalent today, the lines of the 1870s used several gauges, necessitating some means of allowing the interchange of rolling stock. The Rochester and State Line Railroad faced this in Salamanca at its interchange with the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad, with its 6 ft (1,829 mm) gauge. The Ramsey car transfer device solved the problem, although it did little for the inconvenience until the A&GW saw the light of reason and adopted the 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge.

Like many rail companies, the R&SL experienced fiscal embarrassment from time to time. During the construction of the Salamanca line, management devised a means of protecting the locomotives and cars from the tax collectors when back taxes began to accumulate. They sold the rolling stock to themselves, removing it from the tax collectors' reach, and eventually selling the equipment back to the railroad when the pressure eased.

Rolling stock

At the inception of operations, the R&SL had two locomotives, purchased from Brooks Locomotive Works in 1873. The two brightly decorated 4-4-0 engines weighed some thirty tons each and were named the "Rochester" and the "Salamanca." Additionally, the company utilized twenty-five flatcars, a boxcar, a baggage car, and two passenger cars.

All subsequent locomotives were named in honor of company founders and management. They, too, were Brooks 4-4-0 engines and were kept looking sharp. The company acquired Numbers 3 and 4 in 1876, Number 5 in 1877, and 6 through 11 in the following year.

Matters were different in the end. When the R&SL was folded up and sold off, it had eleven deteriorated locomotives, two hundred sixty-eight tired cars, and shops that were barely usable. The trackage was worn, and the bridges were not much better.

Accidents

Only paper railroads never have accidents, and the Rochester and State Line Railroad was no paper tiger.[8] Some of the accident accounts surviving to this day leave much unsaid, such as the 13 June 1878 report that Locomotive No 7 ran over two cows between Salamanca and Gainesville on its very first trip. Others are frighteningly graphic (by today's tame standards) and could have been taken from cheap Hollywood scripts. Case in point: on or about 29 January 1879, Train number two departed Salamanca headed for Ellicottville when its encounter with a washout tossed the locomotive into the water. The fireman managed to escape the wreckage, but the engineer was caught by one foot and trapped between the reversing lever and the firebox. He desperately struggled to keep his head above water and avoid a hot stream coming from a burst pipe in the cab. The water had risen to his chin when he was rescued hours later.

In another story that might have come from the Keystone Kops, had it not taken the ex-cop's life, a policeman-turned-brakeman fell off a train in 1879 and was found only after the crew discovered him missing and went back along the line to find him. 1879 proved a costly year for three carriage riders in Mumford who strayed in front of an on-coming train at the Brown Cut, west of the hamlet. The carriage driver claimed not to have seen the train until too late; when he whipped the horse ahead to avoid it, the horse cleared the tracks but the carriage did not. He suffered a serious injury; one young woman was caught on the pilot and carried halfway to the Spring Creek bridge before the train stopped. She survived, essentially uninjured. The second young woman was thrown seven yards by the impact of the 20-mile-an-hour train and died in minutes from massive head trauma.

In the days of primitive signals, or none at all, collisions often occurred. The heavy fogs of Cattaraugus Valley frequently overcame the feeble lights on cabooses, and faster trains ran into slower ones. On 26 August 1879, a coupler failed on an oil train three miles north of Salamanca, breaking the train in two. The latter half rolled to a stop shortly after the next train smashed into it. The brakeman on the stopped cars died, and the engineer of the second train escaped with serious injuries.

On bad days, the collisions were head-on, when one train would take a single track from which another had not yet cleared. The structural weaknesses of the rolling stock of the day led to trains breaking in two. A coupler might fail on a car in the middle of the train, and - as this was before the automatic brakes used today - one-half of the train would chart its own course. Given the wrong terrain, this sometimes sent a string of cars rolling backward downhill out of control, with predictable results.

Demise

The entertaining fiction that the railroad had been built to serve the rural communities along its route and existed to carry coals to Rochester could not hide the fact that it was a pawn of the Vanderbilts. By 1879, William H Vanderbilt owned most of its stock, and several other Vanderbilts served on its board. Thus, it was a de facto if not a de jure branch of the New York Central Railroad. In a painful irony, the shipment of coal never amounted to much, and even the temporarily lucrative transportation of oil soon ended due to competition by the Erie.

The company was not financially successful. Revenue was inadequate; even debt service could not be maintained. The Vanderbilts no longer found the R&SL particularly attractive, their attention being occupied elsewhere.[note 11] It went into oblivion after defaulting on its bonds. Foreclosure proceedings began on 6 February 1880, with receivership on 21 February. In November, the entire equity of the railroad, including the stock owned by the Vanderbilts, was acquired by a syndicate in New York City. Headed by Walston H Brown,[note 12] it paid $600,000 on 20 January 1881.

One commentator[9] has attributed the failure of this company not to a bad idea or an inadequate market demand for its services but to insufficient capitalization and backers who did not greatly care. If anything, he has characterized the R&SL as the seed for a much better attempt, one which, with a false start, eventually succeeded.

On 29 January 1881, the Rochester and Pittsburgh Railroad was created from the remains of the Rochester and State Line Railroad. Four years later, that line succumbed to bankruptcy and was acquired by Adrian Iselin,[10] at one time a director of the Rochester and Pittsburgh. He broke the company into two, the Pennsylvania operations as the Pittsburgh and State Line Railroad Company, and the New York part as the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railroad. The BR&P would go on to be one of the more successful and useful of the region's railroads.

Notes

- Monroe and Livingston Counties were, at the time, the nation's biggest wheat-producing area. Rochester milled as much as 5,000 barrels of flour a day, and the Rochester wheat trade moved an average of 1,200,000 bushels a year between 1845 and 1855.

- One source erroneously gives his name as Owen Allen.

- The route specification included: Rochester, Scottsville, Mumford, Caledonia, Perry, Castile, Portageville, Belfast, Belmont, Wellsville, and thence along the Genesee River to the Pennsylvania line.

- This was the Silver Lake Railroad, not to be confused with the more real Silver Lake Railroad in New Hampshire.

- Today, Silver Springs.

- Locomotive number 1 was a 4-4-0 "American" type boasting an ornately decorated headlight. It bore on each side a picture of Oliver Allen and is today on display at the Rochester Historical Society.

- It's never that simple. Some of the directors of the corporation were affiliated with other railroads, including the New York Central and Hudson River, and their interests served both railroads, not just the one. In fact, at the end of the company's short life, five board members also occupied seats on the board of the New York Central, including W H Vanderbilt, W K Vanderbilt, and Cornelius Vanderbilt himself.

- Nationally, recovery from the panic did not occur until spring of 1879, when manufacturing industries revived and farm prices rose.

- A hamlet near the north town line on Route 19 in Wyoming County.

- Regrettably, no one at the time saw fit to compose a concerto to mark the occasion.

- The Atlantic and Great Western no longer interested them, nor did they wish access to the Bradford coalfields.

- Also a member of the Seney Syndicate.

References

- "Wnyrails.net". Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- Pietrak, Paul (1992). Buffalo Rochester & Pittsburgh Railway. pp. 5–19.

- Slocum, George Engs (1908). Wheatland, New York. p. 41.

- "Obituary. George J. Whitney" (PDF). New York Times. January 1, 1879.

- Schmidt, Carl F. (1953). History of the Town of Wheatland. p. 96.

- "Maps - Yahoo Search Results". Archived from the original on 2009-03-13. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- "43°08'57.9"N 77°39'03.5"E". Google Maps.

- Fries, William (1994). Train Wrecks and Disasters. pp. 10–19.

- Pietrak, Paul (1992). Rochester Buffalo & Pittsburgh Railway. p. 19.

- "Adrian G. Iselin, Chief Investor of the Rochester and Pittsburgh Coal and Iron Company". McIntyre, Pennsylvania, The Everyday Life Of A Coal Mining Company Town: 1910-1947.