Rock-cut architecture of Cappadocia

Rock-cut architecture in Cappadocia in Central Turkey includes living and work spaces as well as sacred buildings like churches and monasteries, that were carved out of the soft tuff landscape.

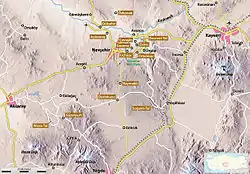

Mount Erciyes south of Kayseri, Mount Hasan southeast of Aksaray, Mount Melendiz in Niğde, and some smaller volcanoes covered the region of Cappadocia with a layer of tuff stone over the course of a twenty million year period ending in prehistoric times, after which erosion created the well-known rock formations of the region.[1] The process is a special form of the rill erosion which affects much of Turkey, in which the solidity of the volcanic tuff and ignimbrite creates particularly deep and steep-sided streams, which create tower-like shapes were they meet at right angles.[2] Since this soft stone is comparatively easy to work, people were probably carving it into dugouts by the early Bronze Age. In the course of time, this progressed to living complexes, monasteries, and whole underground cities. Since 1985, the 'rock sites of Cappadocia' have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[3]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

From traces of settlement it is known that the region of Cappadocia was inhabited in prehistoric times. Whether rock-cuttings had already been made at that time is not clear. It is probable however that in the Bronze Age at the latest, when the region was in the middle of the Hittite empire, the first passageways and rooms had been cut into the rock, as well as reservoirs and possibly even refuges in the cliffs.[4] In Derinkuyu underground city, only one tool of Hittite origin has been found and it might have been brought there at a later date.[5] The earliest attestation of these structures is in Xenophon's Anabasis, which mentions people in Anatolia who had built their houses underground.[6][7]

Their houses were underground, with a mouth like that of a well, but below they spread out widely. Entrance ways were dug for the herd animals, but the people descended by ladder. In the houses there were goats, sheep, cattle, birds, and their children. Inside, all the animals were kept fed on a diet of fodder.

— Xenophon 4.5.25

Christian settlement

The initial Christian settlement of the region came in the first centuries AD, starting with hermits who retreated into the seclusion of the tough landscape from the Christian community at Caesarea. They either settled in caves that already existed or dug their own residences in the cliffs. Since they were seeking solitude rather than protection from enemies, they largely made their homes above ground level. After the Christian church was re-organised under the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus) in the fourth century AD, ever larger groups of Christians followed them over the next few centuries, settling in Cappadocia and building cloistered communities, which meant that they needed ever more and ever larger residential and religious spaces. Meanwhile, in the fourth century, the Isaurians invaded, in the fifth century the Huns, and finally in the sixth century the Sassanid Persians; in 605 the city of Caesarea was conquered during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. These incursions sparked the intensive construction of rock-cut buildings below and above ground, including whole cities. The design of these structures was principally shaped by security and defensive concerns. From 642, the Arabs began to invade the region and these concerns grew increasingly significant, with the result that Christian communities continued to live in the region for three centuries, secure from raids. Eventually, the Byzantines regained control over Cappadocia and under their rule Christianity and Christian architecture in Cappadocia entered a golden age.[8] By the eleventh century, roughly three thousand churches had been carved in the rocks.

In the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV, marking the end of Byzantine rule in Anatolia and the beginning of Turkish pre-eminence in the region. Despite the religious tolerance of the Seljuks, this marked the beginning of the decline of Christianity in Cappadocia and the long decline of church architecture. As a result of the gradual emigration of the Christian inhabitants, the existing cloisters were slowly taken over by Turkish farmers, who renovated them according to their own needs. Since camouflage and defence were no longer necessary, facades and houses were built in front of entranceways that had formerly been hidden and inconspicuous.[8]

The rock-cut houses continued to be used by the Turkish inhabitants in the twentieth century – partially because of the continuously pleasant temperatures under the rock. In 1832, the population had to make use of the underground cities for safety against Egyptian armies during the First Egyptian-Ottoman War. The last remaining Christians left the area in 1923 as part of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The final Turkish inhabitants moved out of the cave settlement at Zelve in the 1950s after earthquakes had done significant damage and made the structures increasingly dangerous. Even today, however, some caves in Uçhisar, Ortahisar, and the Soğanlı valley are still used, at least during the hot summer months, usually with a house attached to them.

Underground cities

The underground cities were well designed for protection against attacks. The few entrances were hidden by foliage and not easily spotted from outside. Inside, they took the form of a labyrinth of passageways which were unnavigable for outsiders, and could be sealed with large rock doors, around a metre high and shaped like mill-stones. These doors were built such that they could be rolled into a closed position relatively easily, but could not be moved from the outside. They had a hole in the centre which was probably used as a kind of peephole. In some cities there were holes in ceiling above, through which the enemy could be attacked with spears.[6] The cities descended up to twelve stories – over 100 metres – under the ground and had everything necessary for a long siege. The upper stories were largely used as stables and storerooms, with a constant temperature of around 10 °C. In the walls of the caverns there were receptacles for various kinds of food, as well as hollows for vessels in which liquids could be stored. Further down, were the living and working spaces, where furniture, including seats, tables, and beds were carved out of the rock. Working spaces include a wine press at Derinkuyu, a copper foundry in Kaymakli, as well as cisterns and wells which ensured a supply of drinking water during a long siege.[9] There were also prisons and toilets.

On the deeper floors there were also monastery cells and churches. The churches in the underground cities are very simple and seldom or never decorated. There are no wall paintings like those found in the later, larger churches like Göreme. Most of them have a cross-shaped ground plan, often with one or two apses. In the rooms near the churches, tombs were cut in the walls. In order to supply the people within with fresh air for breathing, heating, and lighting for a siege of up to six months, there was a complex system of ventilation shafts, which still function today. These also served as the outlet for the smoke from cooking fires in the kitchens.

Nearly forty underground cities are known in Cappadocia, only a small proportion of which are accessible to the public. Further, undiscovered cities may exist. The cities may have originally been linked to one another by kilometre-long passageways, but no such passages have yet been found. Estimates of the number of people in these cities diverge starkly and range between 3,000 and 30,000. The largest is probably the largely unexplored city of Özkonak, located about ten kilometres northwest of Avanos, with perhaps nineteen levels and 60,000 inhabitants,[9] but the best known and most frequented by tourists are Derinkuyu and Kaymakli.

Castles and cliff cities

In contrast to the underground cities are so-called castles or castle-mountains, such as Uçhisar and Ortahisar. These are 60-to-90-metre-high (200 to 300 ft) rock outcrops that are crisscrossed by a tangle of passageways and rooms. As a result of erosion and earthquake damage, parts of these are often now open to the air. The castles also served as refuges from danger and could be sealed with door-stones similar to those in the underground cities. They could accommodate around 1,000 people. The ground-level caverns have been partially integrated into the houses built in front of them and continue to be used as stables and storerooms to this day.

In addition, collections of residences and other rooms are carved into cliff faces. The largest of these is Zelve and the best-known is Göreme, but whole cities of these cliff buildings can also be seen at Soğanlı valley, Gülşehir, and Güzelyurt. At these sites, underground cities are mixed with residential complexes, cloisters, work spaces of other sorts and churches in the steep cliffs.

In these cases, many of the rooms are connected by a branched tunnel system. The entrances are usually open, since the main purpose of these, unlike the underground cities, was not really to be hidden. Nevertheless, entry is sometimes made very difficult by the fact that the vertical cliff-faces had to be clambered up using simple hand and footholds. Inside the internal tunnel system, too, moving around is made difficult by steep, narrow passageways and vertical chimneys. In many of these places, dovecotes are carved in the high cliff walls, often with colourfully painted entrance holes. The colour would attract the birds, which then made their nests in them. These dovecotes were accessed once a year by difficult climbing manoeuvres and the birds' excrement was collected for use as fertiliser.[10][11] Pre-existing holes were converted into dovecotes by cutting niches for nests and walling up entrances.

Churches

The many churches in Cappadocia range from single, completely undecorated rooms in the underground cities that can only be identified as religious spaces by the presence of an altar stone, through cross-in-square churches, to the three-aisle basilica. They are all strongly shaped by Byzantine church architecture.[12] Most have a cross-shaped groundplan, one or more cupolas, barrel vaults or combinations of all these elements. The key difference from built church architecture is the fact that the builders were not constructing a structure and had no need to plan supporting walls and columns since they only had to carve out the rooms from the existing rock. Nevertheless, they incorporated elements from traditional architecture, like columns and pilasters, although they did not actually serve any load-bearing function. The furniture of the churches, including the altars, pews, baptismal fonts, choir seating, and choir screen, were carved out of the rock in most cases.[12] On the outside, the churches are often visible from far away as a result of facades with blind arcades, gables, and columns.

The design of the paintings allows the date of a church's creation to be determined to some degree. While the simple chapels in the underground cities are unpainted, the earliest churches above ground level have simple figural frescoes. One example is the Ağaçaltı Kilesesi[13] in the Ihlara valley, which was probably built in the seventh century. Later churches are decorated only with plain geometric decorations like crosses, zigzag lines, diamonds, and rosettes, which are drawn on the rock walls with red paint. These date from the eighth and early ninth centuries, the period of the Byzantine Iconoclasm. Possibly under Arab-Islamic influence all depictions of Jesus, the apostles, and the saints were forbidden by Leo III as being impious. In the two-storey Church of Saint John in Gülşehir, iconoclastic patterns can still be seen on the lower level.

In the ninth century, the iconoclasm was ended and, from then on, the churches were decorated with ever more complex frescoes. As part of this, the older churches were largely repainted, so relatively few of the old paintings survive. In many un-restored churches, the old geometric patterns can be seen where the more recent plaster is peeling away. Ever more detailed paintings were accomplished in this period, which allows age to be estimated. It is clear that there were template collections for the artists, with the help of which the outlines of the paintings were sketched out and then finally painted. Among the most common paintings were scenes from the life of Jesus, like his nativity, baptism by John the Baptist, miracles, last supper, crucifixion, entombment, and resurrection.[9][6]

Many of the frescoes have been heavily damaged by thrown stones, especially the figure's eyes. These are the result of the later Islamic aniconism. Since the 1980s, many churches have been carefully restored.

Older paintings in Saint John's Church, Gülşehir

Older paintings in Saint John's Church, Gülşehir Later frescoes in Saint John's Church, in Gülşehir, dated by an inscription to 1212[12]

Later frescoes in Saint John's Church, in Gülşehir, dated by an inscription to 1212[12] Iconoclastic paintings in a church in Açıksaray

Iconoclastic paintings in a church in Açıksaray Frescoes in the Karanlık Kilisesi in Göreme from the early twelfth century[14]

Frescoes in the Karanlık Kilisesi in Göreme from the early twelfth century[14]

Research history

The first descriptions of the rock-cut architecture of Cappadocia comes from Xenophon's Anabasis of 402 BC. In the 13th century, the Byzantine author Theodore Skoutariotes mentions the convenient temperatures of the tuff caverns, which were relatively warm through the cold Anatolian winters and pleasantly cool in the hot summer months.[15] In 1906, the German scholar Hans Rott visited Cappadocia and wrote about it in his book Kleinasiatische Denkmäler.[16][17] In the same period, Guillaume de Jerphanion went to the region and wrote the first academic work on the rock-cut churches and their paintings.[16][6]

A systematic investigation of the structures was first undertaken in the 1960s, when the last inhabitants had vacated the rock-cut dwellings. Marcell Restle conducted research on site in the 1960s and published extensive studies on the architecture of the churches built from stone and the paintings of the rock-cut churches. Lyn Rodley investigated the monastery complexes in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the German ethnologist Andus Emge worked on the development of the traditional residential structures in the Cappadocian town of Göreme.

References

- Wolfgang Dorn: Türkei – Zentralanatolien: zwischen Phrygien, Ankara und Kappadokien. DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167, p. 15 bei GoogleBooks

- Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth/Volker Höhfeld: Türkei. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt 2002, p. 50 ISBN 3534137124

- Entry in the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- SpiegelOnline

- Elford/Graf: Reise in die Vergangenheit (Kappadokien). AND Verlag Istanbul, 1976

- Peter Daners, Volher Ohl: Kappadokien. Dumont 1996 ISBN 3-7701-3256-4

- Wolfgang Dorn. Türkei – Zentralanatolien: zwischen Phrygien, Ankara und Kappadokien. DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167, p. 283 (Google Books)

- Katpatuka.org Settlement history

- Michael Bussmann/Gabriele Tröger: Türkei. Michael Müller Verlag 2004 ISBN 3-89953-125-6

- Wolfgang Dorn. Türkei – Zentralanatolien: zwischen Phrygien, Ankara und Kappadokien. DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167, p. 349 bei GoogleBooks

- Archived June 12, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived (Date missing) at kappadokien.dreipage.de (Error: unknown archive URL)

- Agacalti Church

- Karanlik Church

- Cappadocia Academy at the Wayback Machine (archived June 12, 2004)

- Robert G. Ousterhout: A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia.Dumbarton Oaks, 2005, p. 2 ISBN 0884023109, on Google Books

- Suchbuch.de

Bibliography

- Peter Daners, Volker Ohl: Kappadokien. Dumont, Köln 1996, ISBN 3-7701-3256-4

- Andus Emge: Wohnen in den Höhlen von Göreme. Traditionelle Bauweise und Symbolik in Zentralanatolien. Berlin 1990. ISBN 3-496-00487-8

- John Freely: The Companion Guide to Turkey. Boydell Press, 1984.

- Marcell Restle: Studien zur frühbyzantinischen Architektur Kappadokiens. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1979, ISBN 3700102933

- Friedrich Hild, Marcell Restle: Kappadokien (Kappadokia, Charsianon, Sebasteia und Lykandos). Tabula Imperii Byzantini. Wien 1981. ISBN 3-7001-0401-4.

- Marianne Mehling (ed.): Knaurs Kulturführer in Farbe Türkei. Droemer-Knaur, 1987, ISBN 3-426-26293-2

- Lyn Rodley: Cave Monasteries of Byzantine Cappadocia. Cambridge University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0521267984

- Robert G. Ousterhout: A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia. Dumbarton Oaks Studies 42, Harvard University Press 2005, ISBN 0884023109 GoogleBooks

- Rainer Warland: Byzantinisches Kappadokien. Zabern, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-8053-4580-4.

- Fatma Gul Ozturk: Rock Carving in Cappadocia From Past to Present. Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları, 2009,ISBN 978-605-396-069-0.