Rodrigo of Castile

Ruderick (Latin: Rudericus; died on 4 October – 5 November 873), better known by his Spanish name Rodrigo, was an influential noble of the Kingdom of Asturias, and was probably the first Count of Castile (850/862–873) and Álava (867/868–870). He was an active participant in the Reconquista and a faithful vassal of Ordoño I and Alfonso the Great, kings of Asturias. By conquering land from the Moors, Rodrigo began the southern expansion of the County of Castile.

Rodrigo | |

|---|---|

| Count of Castile Count of Álava | |

| Reign | 850/862-873 |

| Predecessor | Position Established |

| eldest son | Diego Rodríguez Porcelos |

| Issue | Diego Rodríguez Porcelos |

| Father | ? Ramiro I of Asturias |

| Mother | ? Paterna |

Origins

Rodrigo's parentage is not historically documented. Some Iberian Muslim writers refer to a brother or brother-in-law of Ordoño I active in Castile, while others assign the same role to a Ruderick without stating a relationship, and the references have been interpreted as referring to the same man. It seems that due to the missions entrusted to him, it is probable that he was close to the royal house.[1] Fernández de Béthencourt placed him as brother of Ordoño I and son of Ramiro I of Asturias by his second wife, Paterna.[2] Were this true, Rodrigo would have become Count of Castile and when still a child, since Ramiro and Paterna did not marry until around 842, making a number of historians consider this unlikely. Barrau-Dihago dismissed this interpretation due to the lack of support from primary sources. An alternative reconstruction would make Rodrigo the brother of Ordoño's wife Munia.

Count of Castile

Rodrigo was created governor of the eastern march (marca oriental) of the realm, the territory called al-Qila by the Arabs, which later became the county of Castile. The area is believed to have earned this name due to the fact that there are few naturally occurring defensible positions, which lead to the creation of castles, or castillos, to defend the region.[3] Rodrigo is traditionally believed to have been made governor in 850, possibly upon Ordoño's assumption of the crown. The primary reason for the introduction of these comital powers was to improve how the eastern regions of Asturias were managed, as they were crucial outposts against the Moors. It was also important for Ordoño to leave these possessions under the control of his relatives and preferably members of his immediate family. In return for their loyalty, these new counts were granted great amounts of freedom.

These appointments also coincided with a rebellion against the Emir led by Musa ibn Musa al-Qasawi of the Muwallad Banu Qasi tribe. Musa allied with Íñigo Arista of Pamplona, but the Asturians and Gascons fought against them at the Battle of Albeda. The Asturians lost not only the battle, but also control of La Rioja. Muwallad rebels were joined by Mozarabs after the Emir appointed Hashim ibn 'Abd al-Aziz as vizier. The Mozarabs of Calatrava took control of their castle and petitioned Ordoño for assistance. It was Count Gatón of El Bierzo who responded by defeating the Moorish forces at Andújar in 853. The Emir's forces continued to fight back, suppressing rebellions and seizing the Ebro valley. By appointing Rodrigo as Count of Castile, Ordoño may have been hoping that Rodrigo could achieve in La Rioja and the Ebro valley what Gatón did in Calatrava.

At this point, Rodrigo's realm (called Bardulia) was limited to a small territory bordered the Ebro River in the east, Brañosera to the west, the Cantabrian Mountains to the north and a line of fortifications, the largest of which were Merindad de Losa and Valle de Tobalina, to the south.[4] The earliest documentation of Rodrigo as count was the foundation charter of San Martín de Ferrand (in Herrán, Burgos) dating from 852, although this is now believed to be a forgery. There are a number of charters under his name claiming to be from 853–862,[5] but the earliest one that can be dated with certainty is from 862: [lower-alpha 1]

Reconquistador

From the very beginning of his reign, Rodrigo took an active part in the Reconquista. In the year 854, Castillan soldiers participated in the capture of Haro, and a little later captured Muslim fortifications in Cerezo de Río Tirón, Carrias and Grañón. Meanwhile, Ordoño I and Rodrigo conducted extensive construction of new fortresses on the Muslim border, among which were Frias and Lantarón.[4]

The first evidence of Count Rodrigo's personal participation in the Reconquista is as one of the participants in the 859 Battle of Monte Laturce.[6] In it, the combined Asturian-Pamplonan army commanded by Ordoño and García Íñiguez of Pamplona defeated the army of Musa ibn Musa, who owned vast territories bordering Asturias and Pamplona. The number of Muslim casualties, according to various sources, ranged from 10,000 to 20,000 soldiers. Musa himself was seriously wounded and until his death in 862 did not campaign against the Christians. Albelda, one of the main Moorish fortifications in the Muslim-Christian borderlands, was destroyed.[7]

When Musa died, his son Lubb (who had inherited Toledo) swore fealty to Ordoño. This allowed the Christians to expand to the south peacefully, both by repopulating the area known as the Desert of the Duero and by being welcomed by Christian-majority cities formerly under Muslim rule. The repopulation efforts were mostly led by the clergy, but Rodrigo also took part in Ordoño's Repoblación, repopulating Amaya in 860.[8][9] Amaya was known as the "patrician city" because at one time it had been the capital of eight of the provinces of the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo which had been conquered in 711-712 by Tariq ibn Ziyad. It had been left empty since Tariq's conquest.

A significant part of Rodrigo's re-settlers were Mozarabs who fled to Asturias from persecution in the Emirate of Cordoba. Having settled Amaya, Rodrigo prepared for the expansion of Castile to the south.[10] Rodrigo constructed fortresses along the new border. These became the basis for the modern municipalities of Úrbel del Castillo, Castil de Peones, Moradillo de Senado (in Burgos) and Villafranca Montes de Oca.[4]

In 863, Count Rodrigo captured and plundered Somosierra owned by the Cordobans.[10] The Castilians seized the fortress of Talamanca de Jarama and captured, but soon released, the local Wali Murzuk and his wife.[11] At the same time, Ordoño ravaged Coria.[7] One chronicle says that in 863, the 'brother of Ordoño' fought Muslim troops.

Military Defeats

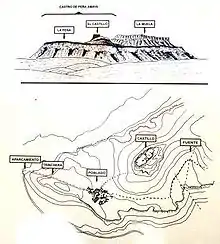

Rodrigo's victories warranted a response from Muhammad I of Córdoba. That year, on Muhammad's orders, his son Abd ar-Rahman and commander Abd al-Malik ibn Abbas went to Álava and Castile and ravaged the border lands of the Kingdom of Asturias, destroying several fortresses and killing many civilians. Count Rodrigo tried to stop the Moors, blocking the gorge near Pancorbo, but Abd ar-Rahman and Abd al-Malik managed to inflict a heavy defeat on the Castilians. According to the Spanish Muslim historian Ibn Idariboth, in battle and during the retreat, the Christians suffered heavy losses, including 19 counts. Only a few Castilians, including Rodrigo.[12]

In 865, a Moorish army of 20,000 soldiers, again led by Abd ar-Rahman and Abd al-Malik, invaded Rodrigo's realm. The Moors captured the Castilian border fortresses that survived after the campaign of 863, including Bordjia belonging to the Count Gundisalvo (or Gonzalo), which some historians identify with Burgos.[13] After this, Abd ar-Rahman and Abd al-Malik inflicted a new defeat to the Count of Castile in the bloody battle at the Battle of the Morcuera near Añana. Despite the fact that the Christian soldiers were the first to attack the Muslims, they retreated and mostly died during the retreat. After leaving Muslim garrisons in the fortresses of Pancorbo, Cereso de Rio Tiron, Ibrillos and Grañón, the Moors returned to Cordoba. These defeats so undermined Castile and Álava, that when Abd ar-Rahman attacked Rodrigo's lands again in 866, the Christians showed no signs of resistance, according to the historian al-Alatira they were not even able to collect the necessary troops.[4] The Moorish sacking of Rodrigo's castles and those of other noblemen in Castile, halted the process of reconquest and repopulation in the area.

In 867, another son of Emir Muhammad I, al-Hakam, led another raid against Count Rodrigo's lands without ever entering the battle. In the same year, the Cordobans faced serious internal difficulties that lasted a decade and a half. This allowed the Castilians under Rodrigo to regain control of the fortresses of La Bureba, Pancorbo (in 870)[14] and Cereso de Rio Tiron, while the Alavians took possession of Cellorigo.[15]

Internal Conflicts

King Ordoño, was succeeded on May 27, 866 by his eldest son Alfonso III of Asturias who at that time was about 18 years old. At the time Alfonso was in Santiago de Compostela. Almost immediately, a rebellion broke out against him, led by Count Fruela Bermudez of Lugo. Fruela captured the Asturian capital of Oviedo and was made king. Alfonso was overthrown and took refuge in Castile. Count Rodrigo quickly raised an army and entered the Kingdom of Asturias to support the young monarch, who was crowned in Oviedo on Christmas Day.[16] Rodrigo was present for the coronation and, like every other lord of the realm, took an oath of loyalty.[15] For his service to the king, Rodrigo was made one of Alfonso's closest advisers.[5]

Rodrigo remained at Oviedo for the winter of 866/867, but had to return to Castile to repel Moorish raiders. Between 867 and 868, he led the suppression of the Alavés rebellion of the Basque magnate Eglyón. Historical sources do not report how Rodrigo did this, but testify that by the end of 868 the rebels were reconciled with the king without Rodrigo ever having to draw his sword.[15] For this service Rodrigo was made count of Álava. Rodrigo appointed a man called Sarrasin Muñez as his Alcalde for Álava. He governed that county until 870, when Vela Jiménez is recorded as count. Even when he was not Count of Álava, Rodrigo retained control of many possessions in the county.[15]

Rodrigo last appears in a document dated 18 April 873, and is said to have died either on 4 October[15][17] or 5 November of the same year, and was succeeded by his son Diego Rodríguez. This happened with the approval of the king, and is the first example of a count inheriting his possessions in Asturias.[18]

Legacy

Rodrigo's role as probable founding count of Castile has led to an amplification of his actual activities, with forged charters pushing his rule in the county a decade earlier than it can reliably be traced. This process has also led to the duplication of himself and his son, in the form of an invention of earlier counts Rodrigo (supposed brother of Aurelius and Vermudo I) and Diego.[19] He is remembered as a shield of Christendom, who took advantage of the weakness of his enemies and reorganised his own defences. He formed the County of Castile and then expanded it, adding a number of fortresses and the city of Amaya. He also secured rights for his county which were passed on to his son Diego and his successors, ensuring the importance of Castile in future generations.

Notes

-

Facta carta in era DCCCCª, regnante Roderico comite in Castella. (Charter dated in the 900th era, Rodrigo governing, count in Castile). Cfr. Collection of charters from San Millán de la Cogolla

.

References

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 157.

- Les noblesses espagnoles au Moyen Âge, par Marie-Claude Gerbet, Armand Collin, p.12.

- Les noblesses espagnoles au Moyen Âge, par Marie-Claude Gerbet, Armand Collin, p.14.

- "Historia del Condado de Castilla. Capítulo III. Rodrigo, el primer conde Castilla (850—873) (I)" (in Spanish). Bardulia. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 158-159.

- "Rodrigo" (in Spanish). Bardulia. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Chronicle of Alfonso III, 26.

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 144.

- Listed as the year 860 in Anales castellanos segundos, Annales Compostellani and Chronicon Burgense

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 147-148.

- Anales castellanos primeros, year 863

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 148-149.

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 152-156.

- Rodrígues-Picavea Matilla E. (2000). La corona de Castilla en la Edad Media. AKAL. p. 10. ISBN 978-8446010869.

- "Historia del Condado de Castilla. Capítulo III. Rodrigo, el primer conde de Castilla (850—873) (II)" (in Spanish). Bardulia. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Anales castellanos primeros, year 866

- Chronica Naierensis places it on 5 October.

- "Historia del Condado de Castilla. Capítulo IV. El Condado de Castilla bajo Diego Rodrígues (873 – c. 885)" (in Spanish). Bardulia. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Martínez Díez 2004, p. 136.

Sources

- Barrau-Dihigo, L. Recherches sur l'histoire politique du royaume Asturien (718-910). Revue Hispanique. 52: 1-360 (1921).

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2004). El Condado de Castilla (711-1038). La historia frente a la leyenda (in Spanish). Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León. ISBN 84-9718-275-8.

- Pérez de Urbel, Justo. "Los Primeros Siglos de la Reconquista (Años 711-1038)" in España Christiana: Comienzo de la Reconquista (711-1038), vol. 6 of Historia de España [dirigida por Don Ramón Menéndez Pidal] (1964), 204–210.