Roger Curtis

Admiral Sir Roger Curtis, 1st Baronet GCB (4 June 1746 – 14 November 1816) was an officer of the British Royal Navy, who saw action in several battles during an extensive career that was punctuated by a number of highly controversial incidents. Curtis served during the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolutionary Wars and was highly praised in the former conflict for his bravery under fire at the Great Siege of Gibraltar, where he saved several hundred Spanish lives at great risk to his own. His career suffered however in the aftermath of the Glorious First of June, when he was heavily criticised for his conduct by several influential figures, including Cuthbert Collingwood. His popularity fell further due to his involvement in two highly controversial courts-martial, those of Anthony Molloy in 1795 and James Gambier in 1810.

Sir Roger Curtis | |

|---|---|

%252C_by_British_school_of_the_18th_century.jpg.webp) Sir Roger Curtis, ca. 1800 | |

| Born | 4 June 1746 Downton, Wiltshire |

| Died | 14 November 1816 (aged 70) |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1762–1816 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Commands held | HMS Senegal HMS Eagle HMS Brilliant HMS Ganges HMS Queen Charlotte HMS Brunswick HMS Canada HMS Powerful HMS Invincible HMS Formidable Cape of Good Hope Station Portsmouth Command |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor |

Ultimately Curtis' career stalled as more popular and successful officers secured active positions; during the Napoleonic Wars, Curtis was relegated to staff duties ashore and did not see action. He died in 1816, his baronetcy inherited by his second son Lucius who later became an Admiral of the Fleet. Modern historians have viewed Curtis as an over-cautious officer in a period when dashing, attacking tactics were admired. Contemporary opinion was more divided, with some influential officers expressing admiration of Curtis and others contempt.

Early life

Roger Curtis was born in 1746 to a gentleman farmer of Wiltshire, also named Roger Curtis, and his wife Christabella Blachford. In 1762 at 16, Curtis travelled to Portsmouth and joined the Royal Navy, becoming a midshipman aboard HMS Royal Sovereign in the final year of the Seven Years' War. Curtis did not see any action before the Treaty of Paris in 1763, and was soon transferred aboard HMS Assistance for service off West Africa. Over the next six years, Curtis moved from Assistance to the guardship HMS Augusta at Portsmouth and then to the sloop HMS Gibraltar in Newfoundland. In 1769, Curtis joined the frigate HMS Venus under Samuel Barrington before moving to the ship of the line HMS Albion in which he was promoted to lieutenant.[1]

Shortly after his promotion, Curtis joined the small brig HMS Otter in Newfoundland and there spent several years operating off the Labrador coastline, becoming very familiar with the local geography and the Inuit peoples of the region. In a report he wrote for Lord Dartmouth, Curtis opined that although the inland regions of Labrador were barren, the coast was an ideal place for a seasonal cod fishery. He also formed a good opinion of the native people, applauding their healthy and peaceful lifestyle.[1] Curtis made numerous exploratory voyages along the Labrador coast and formed close links with the Inuit tribes and Moravian missionaries in the region. His notes and despatches were presented to the Royal Academy by Daines Barrington in 1774, although accusations later surfaced that many of his observations were plagiarised from the notes of a local officer, Captain George Cartwright.[1]

During his time in Newfoundland, Curtis became friends with Governor Molyneux Shuldham who became Curtis' patron and in 1775 assisted his transfer into HMS Chatham off New York City. The following year, with the American Revolutionary War underway, Curtis was promoted to commander and given the sloop HMS Senegal. Curtis performed well in his new command and a year later was again promoted after being noticed by Lord Howe. Howe made Curtis captain of his own flagship HMS Eagle, and the men became close friends.[2]

Career

American Revolutionary War

In 1778, Curtis returned to Britain in Eagle, but refused to carry out an order to sail the ship to the Far East, a refusal which earned the enmity of Lord Sandwich. In December of the same year he was married to Jane Sarah Brady. As punishment for his disobedience Curtis was unemployed for the next two years, before he secured the new frigate HMS Brilliant for service in the Mediterranean in 1780. Ordered to Gibraltar, Brilliant was attacked by a superior Spanish squadron close to the fortress and was forced to escape to British-held Menorca. Curtis's first lieutenant Colin Campbell complained extensively about his captain's refusal to leave port while enemy shipping passed by the harbour, but Curtis was waiting for a 25-ship relief convoy which he met and safely convoyed into Gibraltar, bringing supplies to the defenders of the Great Siege of Gibraltar then in progress.[2]

Although Curtis was personally opposed to British possession of Gibraltar, he took command of a marine unit during the siege, and in the attack by Spanish gunboats and floating batteries in September 1782, Curtis took his men into the harbour in small boats to engage the enemy. During this operation, Curtis witnessed the destruction of the batteries by British 'hotshot' and was able to rescue hundreds of burnt and drowning Spanish sailors from the water. This rescue effort was carried out in close proximity to the Spanish and French force and in constant danger from the detonation of burning Spanish ships, which showered his overcrowded boats with debris and caused several casualties amongst his crews.[2] When Lord Howe relieved the siege, he brought the much-celebrated Curtis back to Britain, where he was knighted for his service and became a society figure, featuring in many newspaper prints.[3] He came under attack however from Lieutenant Campbell, who published a pamphlet accusing him of indecision and a lack of nerve during his time in Brilliant.[1]

During 1783, Curtis was sent to Morocco to renew treaties with the country and then remained in Gibraltar, accepting the Spanish peace treaty delegates at the war's end.[4] Brilliant was paid off in 1784, although Curtis remained in employment during the peace, commanding HMS Ganges as guardship at Portsmouth. In 1787 he was placed on half-pay, although it has been speculated that during this period he conducted a secret mission to Scandinavia to ensure British supplies on naval materials from the region in the event of war.[1] In the Spanish armament of 1790, Curtis was briefly made flag captain of HMS Queen Charlotte under Howe, but soon transferred to HMS Brunswick. As captain of Brunswick, Curtis had to deal with an outbreak of a deadly and infectious fever. He was successful in controlling the disease and later published and advisory pamphlet on techniques for other officers to follow when faced with contagion aboard their ships.[2]

French Revolutionary War service

In 1793 at the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, Curtis returned to Queen Charlotte and joined Lord Howe at the head of the Channel Fleet. In May 1794, Howe led the fleet to sea to search for a French grain convoy and after a month of fruitless searching, discovered that the French Atlantic Fleet under Villaret de Joyeuse had left harbour and was sailing to meet the convoy. Howe gave chase and gradually closed on Villaret's rearguard, fighting two inconclusive actions during the Atlantic campaign of May 1794. On 1 June 1794, Howe caught the French fleet and brought them to battle in the battle of the Glorious First of June. The action was hard-fought and Curtis' ship was heavily engaged, fighting several French ships of the line simultaneously.[5]

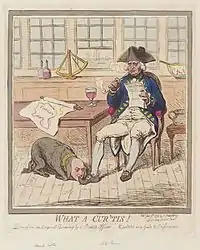

James Gillray, 1795

In the closing stages of the battle, the aged Howe retired to his cabin and Curtis was given responsibility for the flagship and consequently the fleet over the next day.[6] Exactly how much of what transpired was Curtis's fault has never been established, but in a series of unusual decisions the British failed to pursue the defeated French fleet, allowing many battered French ships to escape. Even more controversially, a despatch was sent to the Admiralty concerning the action which praised certain officers and excluded others. The awards presented to the captains who had served at the battle were given based on the praise each captain received in this report, and those omitted were excluded from the medal celebrating the victory and other honours.[7] Although Howe had ultimate responsibility for the despatch, many blamed Curtis for this slight and he was rumoured to have taken the decision to abandon pursuit and subsequently penned the report himself in Howe's name.[2]

Curtis's subsequent actions increased the distrust felt by his fellow officers. While Curtis was granted a baronetcy[8] for his role in the action, another captain, Anthony Molloy, faced a court martial and national disgrace for what was considered to be his failure to engage the enemy during the battle.[6] Curtis stood as prosecutor in the case, and Molloy was subsequently dismissed from his ship and effectively from the service as the result of Curtis's prosecution. Cuthbert Collingwood, one of the captains overlooked by the despatch, subsequently described Curtis as "an artful, sneeking creature, whose fawning insinuating manners creeps into the confidence of whoever he attacks and whose rapacity wou'd grasp all honours and all profits that come within his view".[2]

During the two years following the battle, Curtis had brief periods in command of HMS Canada, HMS Powerful, HMS Invincible and HMS Formidable. In 1796, he was promoted to rear-admiral and raised his flag on HMS Prince. In Prince, Curtis led the blockade of Brest when most of the fleet was paralysed by the Spithead Mutiny.[9] He was also in overall command of the naval operations which succeeded in destroying or driving off much of the French force sent to support the Irish Rebellion of 1798 culminating in the Battle of Tory Island, at which he was not present.[2] Later in the year he joined Lord St Vincent off Cadiz with a squadron of eight ships of the line, and was soon afterwards made a vice-admiral.[10] In 1799, he retired ashore.

Staff service

Curtis's remaining career was based at a series of shore stations, initially as commander-in-chief Cape of Good Hope Station at Cape Town between 1800 and 1803,[11] which he reportedly hated. In 1804 he was promoted to full admiral,[12] and subsequently employed in Britain from 1805 to 1807 as part of the "Commission for revising the civil affairs of His Majesty's navy". This latter role was an important position and Curtis performed well, introducing many beneficial reforms to the service.[2] In 1802 Curtis's eldest son Roger, a post captain in the navy, died suddenly while on duty. In 1809, after 40 years of naval service, Curtis took his final command, that of Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth.[13] In 1810, he performed his last significant duty, when he presided over the highly controversial court martial examining the conduct of Lord Gambier at the Battle of Basque Roads. At the battle, Gambier had failed to support Captain Lord Cochrane and missed an opportunity to destroy the French Brest Fleet. Infuriated, Cochrane attempted to block the proposed vote of thanks awarded to Gambier for the reduced victory from Parliament.[14] Gambier responded by demanding a court martial to pass judgement on his actions. Gambier and Curtis had fought together at the Glorious First of June and had been friends for many years, and Curtis could be counted on by those in authority to "show strong partiality in favour of the accused."[15] Under instructions from the Admiralty, Curtis and the other officers judging the case found in Gambier's favour and the trial inevitably ended with the court pronouncing that Gambier's behaviour "was marked by zeal, judgement, ability, and an anxious attention to the welfare of his majesty's service".[16]

Curtis retired after the trial and died six years later after a peaceful retirement on 14 November 1816 at his residence Gatscombe House, followed a year later by his wife.[11] In 1815, shortly before his death, he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath.[17] The Curtis family also owned a farm in Catherington, Hampshire, the buildings of which was uncovered during land clearance in 2021.[18]

On his death, his son, Lucius Curtis, inherited the baronetcy. Lucius was an experienced post captain who had lost his ship at the Battle of Grand Port but was exonerated at the subsequent court martial and eventually became an admiral of the fleet. Roger Curtis's highly controversial career was noted for a number of prominent public disputes, that resulted in bitterness between Curtis and several of his fellow officers. He was however, brave and resourceful: his actions at Gibraltar even prompted the naming of the Curtis Group, an archipelago of small islands in the Bass Strait between Australia and Tasmania: The islands were apparently given the name because of their physical similarity to Gibraltar.[2] Modern authors have criticised Curtis for his caution at a time when officers were applauded for bravery, but contemporary opinion was more divided: despite his many detractors, Horatio Nelson, who knew him well from their service together in the Mediterranean, described him as "an able officer and conciliating man".[2]

Named in his honour

Port Curtis in Queensland, Australia, was named after him by Matthew Flinders. Curtis had assisted Matthew Flinders with repairs to his ship, HMS Investigator, in Cape Town in October 1801.[19]

Curtis Island, in northern Bass Strait between mainland Australia and Tasmania, was named by Lieutenant James Grant sailing on the Lady Nelson in December 1800.[20]

Cape Roger Curtis, the SW point of Bowen Island in Howe Sound, British Columbia was named for him, as one of the many islands, channels, passages in the area named for heroes and ships of the battle of The Glorious First.

Notes

- Curtis, Sir Roger, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, William H. Whiteley, Retrieved 25 November 2008

- Curtis, Sir Roger, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Roger Knight, Retrieved 19 January 2008

- "No. 12392". The London Gazette. 26 November 1782. p. 5.

- "No. 12457". The London Gazette. 12 July 1783. p. 1.

- James, Vol. 1, p. 158

- Gambier, Fleet Battle and Blockade, p. 39

- James, Vol. 1, p. 181

- "No. 13693". The London Gazette. 12 August 1794. p. 828.

- James, Vol. 2, p. 23

- James, Vol. 2, p. 152

- Hiscocks, Richard (17 January 2016). "Cape Commander-in-Chief 1795-1852". morethannelson.com. morethannelson.com. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- "No. 15695". The London Gazette. 21 April 1804. p. 495.

- History in Portsmouth Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Gambier, The Victory of Seapower, p. 47

- Clowes, p. 269

- James, Vol. 5, p. 125

- "No. 17003". The London Gazette. 15 April 1815. p. 697.

- "Newly-discovered farm ruins belonged to a sneaky admiral". Portsmouth News. 18 May 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- "Port Curtis – port (entry 9103)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Grant, James (1803). The narrative of a voyage of discovery, performed in His Majesty's vessel the Lady Nelson, of sixty tons burthen: with sliding keels, in the years 1800, 1801, and 1802, to New South Wales. Printed by C. Roworth for T. Egerton. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7243-0036-5.

References

Book sources

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume V. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-014-0.

- Editor: Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1996]. Fleet Battle and Blockade. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-363-X.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Editor: Gardiner, Robert (2001) [1998]. The Victory of Seapower. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-359-1.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain. Conway Maritime Press.

- The Naval Chronicle, Volume 6. J. Gould. 1801. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01845-6)

Web sources

- Knight, Roger (2004). "Curtis, Sir Roger". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6961. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Curtis, Sir Roger". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, William H. Whiteley.