Roland Hayes

Roland Wiltse Hayes (June 3, 1887 – January 1, 1977) was an American lyric tenor and composer. Critics lauded his abilities and linguistic skills demonstrated with songs in French, German, and Italian. Hayes’ predecessors as well-known African-American concert artists, including Sissieretta Jones and Marie Selika, were not recorded. Along with Marian Anderson and Paul Robeson, Hayes was one of the first to break this barrier in the classical repertoire when he recorded with Columbia in 1939.[2]

Roland Hayes | |

|---|---|

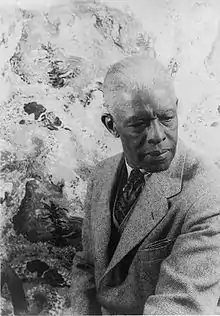

Hayes in 1954, photo by Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born | Roland Wiltse Hayes June 3, 1887 Curryville, Georgia, U.S.[1] |

| Died | January 1, 1977 (aged 89) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, singer |

| Spouse | Helen Alzada Mann (1893-1988) (1932) |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal (1924) |

Early years and family

Hayes was born in Curryville, Georgia, on June 3, 1887, to William Hayes (died ca. 1898) and wife Fannie (or Fanny, née Mann; ca. 1848 – aft. 1920),[3][4] tenant farmers on the plantation where his mother had once been a slave; the Hayes farm appears to be on one of the tracts of land given by a plantation owner named Culpepper to some black people who worked for them. Roland's father, who was his first music teacher, often took him hunting and taught him to appreciate the musical sounds of nature.

When Hayes was 11, his father died, and his mother moved the family to Chattanooga, Tennessee. William Hayes claimed to have some Cherokee ancestry, while his maternal great-grandfather, Aba Ougi (renamed as Charles Mann) was a Chieftain from the Ivory Coast. Aba Ougi was captured and shipped to the United States of America in 1790.[5]

Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Curryville (founded by Roland's mother[6]) is where Roland first heard the music he would cherish forever, Negro spirituals. It was Roland's job to learn new spirituals from the elders and teach them to the congregation. A quote of him talking about beginning his career with a pianist:

I happened upon a new method for making iron sash-weights," he said, "and that got me a little raise in pay and a little free time. At that time I had never heard any real music, although I had had some lessons in rhetoric from a backwoods teacher in Georgia. But one day a pianist came to our church in Chattanooga, and I, as a choir member, was asked to sing a solo with him. The pianist liked my voice, and he took me in hand and introduced me to phonograph records by Caruso. That opened the heavens for me. The beauty of what could be done with the voice just overwhelmed me.[7]

Hayes trained with Arthur Calhoun, an organist and choir director, in Chattanooga. Roland began studying music at Fisk University in Nashville in 1905 although he had only a 6th-grade education. Hayes's mother thought he was wasting money because she believed that African Americans could not make a living from singing. As a student he began publicly performing, touring with the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1911. He furthered his studies in Boston with Arthur Hubbard, who agreed to give him lessons only if Hayes came to his house instead of his studio. He did not want Roland to embarrass him by appearing at his studio with his white students. During his period studying with Hubbard, he worked as a messenger for the Hancock Life Insurance Company to support himself.

Early career

In January 1915 Hayes premiered in Manhattan, New York City in concerts presented by orchestra leader Walter F. Craig.[8] Hayes performed his own musical arrangements in recitals from 1916 to 1919, touring from coast to coast. For his first recital he was unable to find a sponsor so he used 200 dollars of his own money to rent Jordan Hall for his classical recital. To earn money he went on a tour of black churches and colleges in the South. In 1917 he announced his second concert, which would be held in Boston's Symphony Hall. On November 15, 1917, every seat in the hall was sold and Hayes's concert was a success both musically and financially, but the music industry was still not considering him a top classical performer.[9] He sang at Walter Craig's Pre-Lenten Recitals[10] and several Carnegie Hall concerts. He performed with the Philadelphia Concert Orchestra, and at the Atlanta Colored Music Festivals and at the Washington Conservatory concerts. In 1917, he toured with the Hayes Trio, which he formed with baritone William Richardson (singer) and pianist William Lawrence (pianist).

In April 1920, Hayes traveled to Europe. He began lessons with Sir George Henschel, who was the first conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and gave his first recital in London's Aeolian Hall in May 1920 with pianist Lawrence Brown as his accompanist. Soon Hayes was singing in capital cities across Europe and was quite famous. Almost a year after his arrival in Europe, Hayes had a concert at London's Wigmore Hall. The next day, he received a summons from King George V and Queen Mary to give a command performance at Buckingham Palace. He returned to the United States of America in 1923. He made his official debut on November 16, 1923, in Boston's Symphony Hall singing Berlioz, Mozart, and spirituals, conducted by Pierre Monteux, which received critical acclaim. He was the first African-American soloist to appear with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.[11] He was awarded the Spingarn Medal in 1924.

Late career

Hayes finally secured professional management with the Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Company. He was reportedly making $100,000 a year at this point in his career. In Boston he also worked as a voice teacher. One of his pupils was the Canadian soprano Frances James. He published musical scores for a collection of spirituals in 1948 as My Songs: Aframerican Religious Folk Songs Arranged and Interpreted.

In 1925, Hayes had an affair with a married Czech aristocrat, Bertha Henriette Katharina Nadine, Gräfin von Colloredo-Mansfeld (June 21, 1890 in Týnec – January 29, 1982 in Auch), which resulted in a pregnancy.[12] Bertha had been married in Vienna since 10 August 1909 to a member of a German princely family, Hieronymus von Colloredo (November 3, 1870 in Dobříš – August 29, 1942 in Prague), who was 20 years her senior. He refused to allow the expected child to bear his name or to be raised along with the couple's four older children, quietly managing to obtain a divorce in Prague on 8 January 1926, while Bertha left their home in Zbiroh, Czechoslovakia, to bear Hayes's child in Basel, Switzerland. Hayes offered to adopt the child, while the countess sought to resume the couple's relationship, while concealing it, until the late 1920s.[12] Their daughter, Maya Kolowrat, would marry Russian émigré farm-worker, later painter, Yuri Mikhailovich Bogdanoff (January 28, 1928 in Leningrad – 2012). Maya later gave birth in Saint-Lary, Gers, to twins Igor and Grichka Bogdanoff in 1949, who later attributed their early interest in the sciences to their unhampered childhood access to their maternal grandmother's castle library.[3]

After the 1930s, Hayes stopped touring in Europe because the change in politics and the rise of the Nazi Party made it unfavourable to African Americans.[7]

In 1932, while in Los Angeles, for a Hollywood Bowl performance, he married Helen Alzada Mann (1893–1988). The new Mrs. Hayes was born in Chattanooga and graduated from what is now Tennessee State University. One year later they had a daughter, Afrika Hayes.[13] The family moved into a home in Brookline, Massachusetts. In 1943 he sang several times in Britain to entertain troops, and appeared at the Royal Albert Hall on 29 September as the soloist before a 200-member choir of all Black soldiers, and all from USAAF Engineer Aviation Battalions. After the concert he dined at the London residence of Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee, Commanding General of all logistics forces in the European Theater of Operations, who routinely received visiting political, manufacturing, and show business figures in the Theater.

Hayes did not perform very much from the 1940s to the 1970s, but continued yearly concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York and performances at Fisk and other colleges. In 1966, he was awarded the degree of Honorary Doctorate of Music from The Hartt School of Music, University of Hartford. Hayes continued to perform until the age of 85, when he gave his last concert at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge. He was able to purchase the land in Georgia on which he had grown up as a child.[14]

He died on January 1, 1977, five years after his final concert.

Racial reaction

Hayes, before departing from Prague for Berlin in 1924, was warned by American Consul General not to go to Germany until the occupying armies had been withdrawn, as Germans had bitter feelings over being occupied by armies with black troops. An open letter to the American Ambassador was published in a Berlin newspaper, calling "for the prevention of a certain calamity: namely, the concert of an American Negro who has come to Berlin to defile the name of the German poets and composers". despite this protest, Hayes wrote, "I refused to believe ... that they would hold me, a private Negro citizen of the United States, responsible for the presence of French-speaking Africans". Hayes booked his recital at Konzerthaus Berlin with no difficulties. Germans were still unhappy about his appearance in Berlin, and when he appeared on stage several members of the audience began to boo and hiss at the singer. Despite the hostile climate, Hayes began to sing Franz Schubert's "Du bist die Ruh'". Hayes's remarkable voice and musical talent won over the audience and his concert was a success.[15]

Hayes's wife and daughter mistakenly sat in seats reserved for white customers in a shoe store in Rome, Georgia in 1942. An argument erupted which resulted in the two leaving. Later, Hayes confronted the store owner, whom he knew, and resolved the conflict. Upon leaving, Hayes was assaulted by police and put under arrest, with his wife also being taken into custody. Gradually the story received national attention and much sympathy for Hayes. The assaulting police officer was fired, with federal charges made against him.[16] A poem by Langston Hughes, entitled "How About It, Dixie", refers to the incident.[17]

Hayes faced heavy criticism from anti-Jim Crow activists for performing in an integrated theater in Washington, D.C., on January 5, 1926, followed by a segregated theater in Baltimore, Maryland, on January 7, 1926.[18]

Hayes taught at Black Mountain College for the 1945 Summer institute where his public concert was, according to Martin Duberman, "one of the great moments in Black Mountain's history".[19] After this concert, in which unsegregated seating went well, the school had its first full-time black student and full-time member of the faculty.[20]

Legacy

- In 1982, the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga opened a new musical performance center, the Roland W. Hayes Concert Hall. The concert venue is located at the Dorothy Patten Fine Arts center.

- The Roland Hayes Committee was formed in 1990 to advocate the induction of Roland Hayes into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame. In 1992, when the Calhoun Gordon Arts Council was incorporated, the Roland Hayes Committee became the Roland Hayes Music Guild and Museum in Calhoun, Georgia. The opening was attended by his daughter Afrika.

- There is a historical marker located on the grounds of Calhoun High School (Calhoun, Georgia) on the north-west corner of the campus near the front of the Calhoun Civic Auditorium.[21]

- Hartford Stage and City Theatre (Pittsburgh) shared the world premiere of Breath & Imagination by Daniel Beaty, a musical based on the life of Hayes, on January 10, 2013.

- Part of Georgia State Route 156 was named for Hayes.[22]

- A bronze plaque, mounted on a granite post, marks Hayes's home, at 58 Allerton Street in Brookline, Massachusetts. The plaque was dedicated on June 12, 2016, in a ceremony in front of the home in which Hayes lived for almost fifty years. The ceremony was attended by his daughter Afrika, former Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, Brookline Town officials, and many more.

- A school in Roxbury, Massachusetts is named after him. The Roland Hayes School of Music currently instructs courses for 9-12 grade students of the John D. O'Bryant School of Mathematics & Science and shared in the past with Madison Park Technical Vocational High School part of the Boston Public Schools system.[23]

Discography

LPs

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Bordman (piano) – The Life of Christ (Amadeo, 1954)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) – Negro Spirituals (Amadeo, 1955)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "Roland Hayes Sings" (Amadeo AVRS 6033)(Vanguard)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "Roland Hayes - Christmas Carols of the Nations" (Vanguard VRS7016, 195?)(10")

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "The Life of Christ" (Vanguard VRS462, 1954)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "My Songs" (Vanguard VRS494, 1956)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "The Art of Roland Hayes: Six Centuries of Song" (Vanguard VRS448/9, 1966)(2 LP)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "The Life of Christ" (Vanguard Everyman SRV352SD, 1976)

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "Afro-American Folksongs" (Pelican LP2028, 1983)

CDs

- Roland Hayes (vocal), Reginald Boardman (piano) - "The Art of Roland Hayes" (Smithsonian Collection of Recordings RD041, 1990)

- The Art of Roland Hayes: Six Centuries of Song (Preiser, 2010)

References

- Horne, Gerald; Young, Mary (2001). W.E.B. Du Bois: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-313-29665-9.

- Story, Rosalyn (January 1, 1991). "Review of The Art of". American Music. 9 (4): 427–430. doi:10.2307/3051692. JSTOR 3051692.

- "Ancestry of Igor and Grichka Bogdanov".

- Christopher A. Brooks, "The unique bond between Roland Hayes and his mother", Indiana University Press blog, February 13, 2015.

- The University of North Carolina library extension publication, Vols 10–11 (1944), p. 25.

- ""Who is Roland Hayes?"" (PDF).

- "AFROCENTRIC VOICES: Roland Hayes Biography". afrovoices.com. Retrieved 2016-02-24.

- Brooks 2015, p. 36.

- Tim Brooks, Richard Keith Spottswood, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890–1919, University of Illinois Press, 2004.

- Nettles, Darryl Glenn (March 1, 2003). African American Concert Singers Before 1950. McFarland. p. 29. ISBN 9780786414673.

- Canarina, John (2003). Pierre Monteux, Maître. Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press, p. 71.

- Brooks, Christopher A. 2015, pp. 358, 361–362, 366–367, 379.

- "Afrika Hayes Interview: Growing Up With Roland Hayes", Schiller Institute. Reprinted from the Summer 1994 issue of FIDELIO Magazine.

- Chris Hillyard, "Gordon County’s Gift To The World: Remembering Roland Hayes"[Usurped!], Reflections (Georgia African American Historic Preservation Network), Vol. XIII, No. 4, February/March 2017, p. 3. Originally published in Calhoun Magazine, Jan/Feb 2017.

- Kira Thurman, "A History of Black Musicians in Germany and Austria, 1870-1961: Race, Performance, and Reception" (2013), p. 145-146

- Christopher A. Brooks, Robert Sims "Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor" (2014), p. 242-255

- "How About It, Dixie" Archived 2017-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. in The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, p. 291, note p. 659; first published in New Masses (October 20, 1942).

- Christopher A. Brooks, Robert Sims "Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor" (2014), p. 147-148

- Duberman, Martin (2009). Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community. Northwestern University Press. p. 215.

- Biography at the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- "Georgiaencyclopedia.org". Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- "Gordon County". Calhoun Times. September 1, 2004. p. 94. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- "Roland Hayes School of Music Band Program". Roland Hayes School of Music Band Program. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

Further reading

- Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. W. W. Norton & Company; 3rd edition. ISBN 0-393-97141-4

- MacKinley Helm, Angel Mo' and her son, Roland Hayes. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1942.

- Brooks, Christopher A., and Robert Sims, Roland Hayes: The Legacy of an American Tenor. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015, pp. 358, 361–362, 366–367, 379. ISBN 978-0-253-01536-5.

- Brooks, Tim, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919, 436–452, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004. Hayes's recording history, beginning in 1911.

External links

- Roland Hayes bio

- Roland Hayes Museum at the Harris Arts Center

- Roland Hayes at AllMusic

- Roland Hayes discography at Discogs

- 1920 passport photo of Roland Hayes

- The Musical Legacy of Roland Hayes. PBS documentary

- Roland Hayes historical marker