Romesh Chunder Dutt

Romesh Chunder Dutt CIE (Bengali: রমেশচন্দ্র দত্ত; 13 August 1848 – 30 November 1909) was an Indian civil servant, economic historian, translator of Ramayana and Mahabharata. He was one of the prominent proponents of Indian economic nationalism.[1]

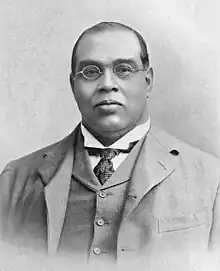

Romesh Chunder Dutt | |

|---|---|

Romesh Chunder Dutt, c. 1911 | |

| Born | 13 August 1848 |

| Died | 30 November 1909 (aged 61) Baroda State, British India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Alma mater | University of Calcutta University College London |

| Occupation(s) | Historian, economist, linguist, civil servant, politician |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse | Manomohini Dutt (née Bose) |

Early life and education

Dutt was born into a distinguished Bengali Maulika Kayastha family. His parents were Thakamani and Isan Chunder Dutt, a Deputy Collector in Bengal, whom Romesh often accompanied on official duties. He was educated in various Bengali District schools, then at Hare School, Calcutta. After his father's untimely death in a boat accident in eastern Bengal, his uncle, Shoshee Chunder Dutt, an accomplished writer, became his guardian in 1861. He wrote about his uncle, "He used to sit at night with us and our favorite study used to be pieces from the works of the English poets."[2] He was a relative of Toru Dutt, one of nineteenth century Bengal's most prominent poets.

He entered the University of Calcutta, Presidency College in 1864. He passed the First Arts examination in 1866, ranking second in order of merit and won a scholarship. While still a student in the B.A. class, without his family's permission, he and two other friends, Behari Lal Gupta and Surendranath Banerjee, left for England in 1868.[3]

At that time, only one other Indian, Satyendra Nath Tagore, had qualified for the Indian Civil Service. Dutt aimed to emulate Tagore's feat. For a long time, before and after 1853, the year the ICS examination was introduced in England, only British officers were appointed to covenanted posts.[4]

At University College London, Dutt continued to study British writers. He qualified for the Indian Civil Service in the open examination in 1869,[5] taking the third place.[6] He was called to the bar by the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple on 6 June 1871.[7]

His wife was Manomohini Dutt and his children were Bimala Dutt, married to Bolinarayan Bora, the first civil engineer from Assam, Kamala Dutt, married to Pramatha Nath Bose, Sarala Dutt, married to Jnanendranath Gupta, ICS, and Ajoy Chandra Dutt, an Oxonian, who was a Professor of Law at Calcutta University and later a Member of the Bengal Legislative Assembly in 1921. His grandsons were Indranarayan Bora, Modhu Bose and Major Sudhindranath Gupta, who retired as the first Indian Commercial Traffic Manager of the BNR.

Career

Pre-retirement

He entered the Indian Civil Service as an assistant magistrate of Alipur in 1871. A famine in Meherpur district of Nadia in 1874 and another in Dakhin Shahbazpur (Bhola District) in 1876, followed by a disastrous cyclone, required emergency relief and economic recovery operations, which Dutt managed successfully. He served as administrator for Backerganj, Mymensingh, Burdwan, Donapur, and Midnapore. He became Burdwan's District Officer in 1893, Commissioner (offtg.) of Burdwan Division in 1894, and Divisional Commissioner (offtg.) for Orissa in 1895. Dutt was the first Indian to attain the rank of divisional commissioner.[6]

Post-retirement

Dutt retired from the ICS in 1897. In 1898 he returned to England as a lecturer in Indian History at University College, London where he completed his famous thesis on economic nationalism. He returned to India as dewan of Baroda State, a post he had been offered before he left for Britain. He was extremely popular in Baroda where the king, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, along with his family members and all other staff members used to call him ‘Babu Dewan’, as a mark of personal respect. In 1907, he also became a member of the Royal Commission on Indian Decentralisation.[8][5]

Politics

He was the president of Indian National Congress in 1899. He was also a member of the Bengal Legislative Council.

Academics

Literature

He served as the first president of Bangiya Sahitya Parishad (Bengali: বঙ্গীয় সাহিত্য পরিষদ) in 1894, while Rabindranath Tagore and Navinchandra Sen were the vice-presidents of the society.[9]

His The Literature of Bengal presented "a connected story of literary and intellectual progress in Bengal" over eight centuries, commencing with the early Sanskrit poetry of Jayadeva. It traced Chaitanya's religious reforms of the sixteenth century, Raghunatha Siromani's school of formal logic, and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar's brilliance, coming down to the intellectual progress of the nineteenth century Bengal.[10] This book was presented by Thacker, Spink & Co. in Calcutta and Archibald Constable in London in 1895, but the idea had formed earlier in Dutt's mind while he managed famine relief and economic recovery operations in Dakhin Shahbazpur. It had appeared originally under the disguise of an assumed name in 1877. It was dedicated to his esteemed uncle, Rai Shashi Chandra Dutt Bahadur.

History

He was a major economic historian of India of the nineteenth century. His thesis on de-industrialization of India under the British rule remains forceful argument in Indian historiography. To quote him:

India in the eighteenth century was a great manufacturing as well as great agricultural country, and the products of the Indian loom supplied the markets of Asia and of Europe. It is, unfortunately, true that the East Indian Company and the British Parliament ... discouraged Indian manufactures in the early years of British rule in order to encourage the rising manufactures of England . . . millions of Indian artisans lost their earnings; the population of India lost one great source of their wealth.[11]

He also directed attention to the deepening internal differentiation of Indian society appearing in the abrupt articulation of local economies with the world market, accelerated urban-rural polarisation, the division between intellectual and manual labour, and the toll of recurrent devastating famines.[12]

Awards

Death

While still in office, he died in Baroda at the age of 61 on 30 November 1909.[13]

Works

- Romesh Chunder Dutt (1896). Three Years in Europe, 1868 to 1871. S. K. Lahiri.

Dutt +Three Years in Europe.

- Romesh Chunder Dutt (1874). The Peasantry of Bengal. Thacker, Spink & Co.

the peasantry of bengal.

; ed. Narahari Kaviraj, Calcutta, Manisha (1980) - Romesh Chunder Dutt (1895). The Literature of Bengal. T. Spink & co.

the literature of bengal.

; 3rd ed., Cultural Heritage of Bengal Calcutta, Punthi Pustak (1962). - Mādhabī kaṅkaṇa in Bengali (1879)

- Rajput jivan sandhya (1879); Pratap Singh: The Last of the Rajputs, A Tale of Rajput Courage and Chivalry, tr. Ajoy Chandra Dutt. Calcutta: Elm Press (1943); Allahabad, Kitabistan, (1963)

- Rig Veda translation into Bengali (1885): R̥gveda saṃhitā / Rameśacandra Dattera anubāda abalambane ; bhūmikā, Hiraṇmaẏa Bandyopādhyāẏa, Kalakātā, Harapha (1976).

- Hinduśāstra : naẏa khaṇḍa ekatre eka khaṇḍe / Rameśacandra Datta sampādita, Kalikātā, Satyayantre Mudrita, 1300; Niu Lāiṭa, 1401 [1994].

- A History of Civilization in Ancient India, Based on Sanscrit Literature. 3 vols. Thacker, Spink and Co.; Trübner and Co., Calcutta-London (1890) Reprinted, Elibron Classics (2001).

- A Brief History of Bengal, S.K. Lahiri (1893).

- Lays of Ancient India: Selections from Indian Poetry Rendered into English Verse. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner (1894); Rupa (2002). ISBN 81-7167-888-2

- Reminiscences of a Workman's Life: verses Calcutta, Elen Press, for private circulation only (1896); Calcutta: n.p. (1956).

- England and India: a record of progress during a hundred years, 1785–1885 (1897); New Delhi, India : Mudgal Publications, 1985.

- Mahabharata: the epic of India rendered into English verse, London: J. M. Dent and Co., 1898. Maha-bharata, The Epic of Ancient India Condensed into English Verse Project Gutenberg, on line.

- The Ramayana: the epic of Rama rendered into English verse, London: J.M. Dent and Co., 1899.

- The Ramayana and the Mahabharata: the great epics of ancient India condensed into English verse, London: J.M. Dent and Co., 1900. Everyman's Library reprint (London: J.M. Dent and Sons; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1910). xii, 335p. Internet Sacred Texts Archive.

- Shivaji; or the morning of Maratha life, tr. by Krishnalal Mohanlal Jhaveri. Ahmedabad, M. N. Banavatty (1899). Also: tr. by Ajoy C. Dutt. Allahabad, Kitabistan (1944).

- The Civilization of India (1900)

- Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London, Trübner (1900); 2005 ed. Adamant Media Corporation, Elibron Classics Series ISBN 1-4021-5115-2.

- Indian Famines, Their Causes and Prevention Westminster, P. S. King (1901)

- The lake of palms. A story of Indian domestic life, translated by the author. London, T.F. Unwin (1902); abridged by P.V. Kulkarni, Bombay, n.p. (1931).

- The Economic History of India Under Early British Rule. From the Rise of the British Power in 1757 to the Accession of Queen Victoria in 1837. Vol. I. London, Kegan Paul, Trench Trübner (1902) 2001 edition by Routledge, ISBN 0-415-24493-5. On line, McMaster ISBN 81-85418-01-2

- The Economic History of India in the Victorian Age. From the Accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 to the Commencement of the Twentieth Century, Vol. II. London, Kegan Paul, Trench Trübner (1904) On line. McMaster ISBN 81-85418-01-2

- Indian poetry. Selected and Rendered into English by R.C. Dutt London: J. M. Dent (1905).

- History of India, Volume 1 (1907)

- The Slave Girl of Agra: An Indian Historical Romance, Based on Madhavikankan. London: T.F. Unwin (1909); Calcutta, Dasgupta (1922).

- Vanga Vijeta; in translation, Todar Mull: The Conqueror of Bengal, trans. by Ajoy Dutt. Allahabad: Kitabitan, 1947.

- Sachitra Guljarnagar, tr. by Satyabrata Dutta, Calcutta, Firma KLM (1990)

References

- Ahir, Rajiv (2018). A Brief History of Modern India. Spectrum Books (P) Limited. p. 15. ISBN 978-81-7930-688-8.

- R. C. Dutt (1968) Romesh Chunder Dutt, Internet Archive, Million Books Project. p. 10.

- Jnanendranath Gupta, Life and Works of Romesh Chandra Dutt, CIE, (London: J.M.Dent and Sons Ltd., 1911); while young Romesh came out unnoticed, Beharilal, possibly his closest friend ever, was chased all the way down to the Calcutta docks by his "poor" father, who could not, however, successfully persuade his son to return to the safety of his parental home. Later, in England, both the friends took the civil service examination successfully, becoming the 2nd and 3rd Indians to join the ICS. The third person in the group, Surendranath Banerjee, also cleared the test, but was incorrectly disqualified, as being over-age.

- Nitish Sengupta (2002) History of the Bengali-speaking People, UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt. Ltd. p. 275. ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- "Selected Poetry of Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848–1909)", University of Toronto (2002).

- S. K. Ratcliffe (1910) A Note on the Late Romesh C. Dutt, in the Everyman's Library edition The Ramayana and the Mahabharata Condensed into English Verse. London: J.M. Dent and Sons and New York: E.P. Dutton. p. ix.

- Renu Paul (2010-10-07) South Asians at the Inns: Middle Temple. law.wisc.edu

- Hansard, HC Deb 26 August 1907 vol 182 c149

- Mozammel, Md Muktadir Arif (2012). "Vangiya Sahitya Parishad". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Romesh Chunder Dutt (1895). The Literature of Bengal. T. Spink & Co. (London); Constable (Calcutta).

the literature of bengal.

; 3rd ed., Cultural Heritage of Bengal Calcutta, Punthi Pustak (1962). - The Economic History of India Under Early British Rule, vol. 1, 2nd ed. (1906) pp. vi–vii, quoted by Prasannan Parthasarathi, "The Transition to a Colonial Economy: Weavers, Merchants and Kings in South India 1720–1800", Cambridge U. Press. On line, excerpt.

- Manu Goswami, "Autonomy and Comparability: Notes on the Anticolonial and the Postcolonial", Boundary 2, Summer 2005; 32: 201 – 225 Duke University Journals.

- "Dutt, Romesh Chunder [Rameshchandra Datta]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32943. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

- Works by Romesh Chunder Dutt at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Romesh Chunder Dutt at Internet Archive

- Works by Romesh Chunder Dutt at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- S. K. Ratcliffe, A Note on the Late Romesh C. Dutt, The Ramayana and the Mahabharata condensed into English Verse (1899) at Internet Sacred Texts Archive

- J. N. Gupta, Life and Works of Romesh Chunder Dutt, (1911) Digital Library of India, Bangalore, barcode 2990100070832 On line.

- Islam, M Mofakharul (2012). "Dutt, Romesh Chunder". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- R. C. (Rabindra Chandra) Dutt, Romesh Chunder Dutt, (1968) Internet Archive, Million Books Project

- Bhabatosh Datta, "Romesh Chunder Dutt", Congress Sandesh, n.d.

- Shanti S. Tangri, "Intellectuals and Society in Nineteenth-Century India", Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Jul., 1961), pp. 368–394.

- Pauline Rule, The Pursuit of Progress: A Study of the Intellectual Development of Romesh Chunder Dutt, 1848–1888 Editions Indian (1977)