Romualdo Formation

The Romualdo Formation is a geologic Konservat-Lagerstätte in northeastern Brazil's Araripe Basin where the states of Pernambuco, Piauí and Ceará come together. The geological formation, previously designated as the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation, named after the village of Santana do Cariri, lies at the base of the Araripe Plateau. It was discovered by Johann Baptist von Spix in 1819. The strata were deposited during the Aptian stage of the Early Cretaceous in a lacustrine rift basin with shallow marine incursions of the proto-Atlantic. At that time, the South Atlantic was opening up in a long narrow shallow sea.

| Romualdo Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Early Albian ~ | |

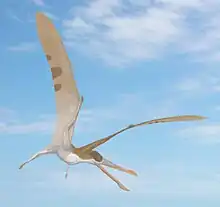

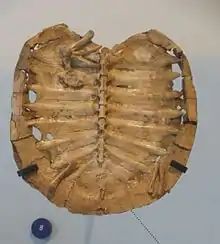

Fossils of Anhanguera (top) and Santanadactylus (bottom) from the Romualdo Formation | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Santana Group |

| Underlies | Exu & Arajara Formations |

| Overlies | Crato & Ipubi Formations |

| Thickness | 2–10 m (6.6–32.8 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Mudstone |

| Other | Limestone, shale |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 7.2°S 39.3°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 12.2°S 10.7°W |

| Region | Pernambuco, Piauí & Ceará |

| Country | |

| Extent | Araripe Basin |

Extent of the Santana Group, to which the Romualdo Formation belongs, in blue | |

The Romualdo Formation earns the designation of Lagerstätte due to an exceedingly well preserved and diverse fossil faunal assemblage. Some 25 species of fossil fishes are often found with stomach contents preserved, enabling paleontologists to study predator–prey relationships in this ecosystem. There are also fine examples of pterosaurs, reptiles and invertebrates, and crocodylomorphs. Even dinosaurs are represented (Spinosauridae, Tyrannosauroidea, Compsognathidae). The unusual taphonomy of the site resulted in limestone accretions that formed nodules around dead organisms, preserving even soft parts of their anatomy. In preservation, the nodules are etched away with acid, and the fossils often prepared by the transfer technique.[1]

Local mining activities for cement and construction damage the sites. Trade in illegally collected fossils has sprung up from the decade of 1970, driven by the remarkable state of preservation and beauty of these fossils and amounting to a considerable local industry. An urgent preservation program is being called for by paleontologists.[2]

In addition, the weathering of Romualdo Formation rocks has contributed soil conditions unlike elsewhere in the region. The Araripe manakin (Antilophia bokermanni) is a very rare bird that was discovered only in the late 20th century; it is not known from anywhere outside the characteristic forest that grows on the Chapada do Araripe soils formed ultimately from Romualdo Formation rocks.

Geology and dating

The Crato Formation was previously considered the lowest member of the then Santana Formation, but has been elevated to a formal formation. The Crato Formation is the product of a single phase, where complicated sequence of sediment strata reflect changeable conditions in the opening sea. The age of the Romualdo Formation, formerly known as the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation, has been controversial, though most workers have agreed that it lies on or near the Aptian-Albian boundary, about 112 million years ago. Nevertheless, a Cenomanian age cannot be ruled out.[3][4]

The extent of the Crato unit and its relationship to the Romualdo Formation had long been ill-defined. It was not until a 2007 volume on the unit by Martill, Bechly and Loveridge that the Crato Formation was given a formal type locality, and was formally made a distinct formation separate from the Romualdo Formation, which is about 10 Ma younger.[3]

Fossil content

Archosaurs

Indeterminate remains of non-avian theropods, avialans, ornithischians, and possibly oviraptorosaurs have been found in Ceara state, Brazil.[5] The oviraptorosaurian remains have been re-identified as megaraptoran fossils.[6]

Dinosaurs

| Dinosaurs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Notes | Images |

| Angaturama[5] | A. limai | Ceará | Spinosauridae. Partial skull (rostralmost portion).[7] Possible junior synonym of Irritator challengeri. |  |

| Aratasaurus[8] | A. museunacionali | Ceará | A coelurosaur. Partial right hindlimb. |  |

| Irritator[5][9] | I. challengeri | Ceará | Spinosauridae. Partial skull (posterior half); one of the most complete spinosaurid skulls known. |  |

| Mirischia[5] | M. asymmetrica | Pernambuco | Compsognathidae. Pelvis and partial left hindlimb. |  |

| Santanaraptor[5] | S. placidus | Ceará | A possible tyrannosauroid. Some caudal vertebrae, partial pelvis, most of both hindlimbs.[10] |  |

Crocodylomorphs

| Crocodylomorphs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Notes | Images |

| Araripesuchus | A. gomesii | Romualdo Formation | Type specimen 423-R is a single skull articulating with part of a lower jaw. A more complete specimen, AMNH 24450, is at the American Museum of Natural History. |  |

| Caririsuchus | C. camposi | Romualdo Formation | A peirosaurid crocodyliform. | |

Pterosaurs

| Pterosaurs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Images |

| Anhanguera |

|

||

| Araripedactylus | A. dehmi | ||

| Araripesaurus | A. castilhoi | ||

| Barbosania[11] | B. gracilirostris | ||

| Brasileodactylus | B. araripensis | ||

| Cearadactylus | C. atrox |  | |

| C. ligabuei | |||

| Kariridraco | K. dianae |  | |

| Maaradactylus | M. kellneri |  | |

| Santanadactylus |

|

| |

| Tapejara | T. wellnhoferi |  | |

| Thalassodromeus | T. sethi |  | |

| Tropeognathus | T. mesembrinus |  | |

| Tupuxuara |

|

| |

| Unwindia | U. trigonus | ||

Turtles

| Turtles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Presence | Notes | Images |

| Santanachelys | S. gaffneyi | [12] |  | |

| Cearachelys | C. placidoi | [13] |  | |

| Araripemys | A. barretoi | [14] |  | |

| Euraxemys | E. essweini | [15] | ||

| Brasilemys | B. josai | [16] | ||

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

Fish

- Araripelepidotes

- Beurlenichthys ouricuriensis[17]

- Brannerion[18]

- Calamopleurus[18]

- Cladocyclus[18][19]

- Enneles audax[20]

- Iemanja palma[21]

- Lepidotes wenzai[16]

- Microdon penalvai[16]

- Notelops[18]

- Obaichthys[16]

- Oshunia brevis[16]

- Placidichthys bidorsalis[22]

- Rhacolepis[18]

- Iansan beurleni[16][23]

- Santanaclupea silvasantosi

- Tharrhias[18]

- Tribodus limae[16]

- Vinctifer[18][24]

See also

References

- Maisey et al., 1991, pp. 99–103

- Gibney, Elizabeth (6 March 2014). "Brazil clamps down on illegal fossil trade". Nature. 507 (7490): 20. Bibcode:2014Natur.507...20G. doi:10.1038/507020a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24598620.

- Martill et al., 2007

- Martill, 2007

- Weishampel, 2004, pp. 563–570

- Aranciaga Rolando, Alexis M.; Brissón Egli, Federico; Sales, Marcos A.F.; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Canale, Juan I.; Ezcurra, Martín D. (2018). "A supposed Gondwanan oviraptorosaur from the Albian of Brazil represents the oldest South American megaraptoran". Cretaceous Research. 84: 107–119. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.10.019. ISSN 0195-6671.

- "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 73.

- Juliana Manso Sayão; Antônio Álamo Feitosa Saraiva; Arthur Souza Brum; Renan Alfredo Machado Bantim; Rafael Cesar Lima Pedroso de Andrade; Xin Cheng; Flaviana Jorge de Lima; Helder de Paula Silva; Alexander W. A. Kellner (2020). "The first theropod dinosaur (Coelurosauria, Theropoda) from the base of the Romualdo Formation (Albian), Araripe Basin, Northeast Brazil". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): Article number 10892. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67822-9. PMC 7351750. PMID 32651406.

- Martill, D. M.; Cruickshank, A. R. I.; Frey, E.; Small, P. G.; Clarke, M. (1 February 1996). "A new crested maniraptoran dinosaur from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 153 (1): 5–8. Bibcode:1996JGSoc.153....5M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.153.1.0005. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 131339386.

- "Table 5.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 114.

- Elgin & Frey, 2011

- Santanachelys gaffneyi at Fossilworks.org

- Juazeiro do Norte at Fossilworks.org

- Araripemys barretoi type locality at Fossilworks.org

- Crato at Fossilworks.org

- Chapada do Araripe at Fossilworks.org

- Casa de Pedra at Fossilworks.org

- Fara et al., 2005, p.152

- Buxéxé, Santana do Cariri at Fossilworks.org

- Enneles audax

- Iemanja palma

- Placidichthys type locality at Fossilworks.org

- Maisey, John G. (1 April 2000). "Continental break up and the distribution of fishes of Western Gondwana during the Early Cretaceous". Cretaceous Research. 21 (2): 281–314. doi:10.1006/cres.1999.0195. ISSN 0195-6671.

- Ze Gomes at Fossilworks.org

Bibliography

- Cavalcanti Duque, Rudah Ruano; Franca Barreto, Alcina Magnólia (2018). "Novos Sítios Fossilíferos da Formação Romualdo, Cretáceo Inferior, Bacia do Araripe, Exu, Pernambuco, Nordeste do Brasil - New Fossiliferous Sites of the Romualdo Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Araripe Basin, Exu, Pernambuco, Northeast of Brazil". Anuário do Instituto de Geociências, UFRJ. 41: 5–14. doi:10.11137/2018_1_05_14. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Elgin, Ross A.; Frey, Eberhard (20 April 2011). "A new ornithocheirid, Barbosania gracilirostris gen. et sp. nov. (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous) of NE Brazil". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 130 (2): 259. doi:10.1007/s13358-011-0017-4. ISSN 1664-2384. S2CID 89178816.

- Fabin, Carlos E.; Correia Filho, Osvaldo J.; Alencar, Márcio L.; Barbosa, José A.; de Miranda, Tiago S.; Neumann, Virgínio H.; Gomes, Igor F.; de Santana, Felipe R. (2018). "Stratigraphic Relations of the Ipubi Formation: Siliciclastic-Evaporitic Succession of the Araripe Basin" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 90 (2 suppl 1): 2049–2071. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201820170526. PMID 29947671. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- Fara, Emmanuel; Saraiva, Antônio Á.F.; Campos, Díogenes de Almeida; Moreira, João K.R.; de Carvalho Siebra, Daniele; Kellner, Alexander W.A. (2005). "Controlled excavations in the Romualdo Member of the Santana Formation (Early Cretaceous, Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil): stratigraphic, palaeoenvironmental and palaeoecological implications" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 218 (1–2): 145–160. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.12.012. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Maisey, J.G.; Rutzky, I.; Blum, S.; Elvers, W. (1991). Laboratory Preparation Techniques. In Maisey, j:G. (ed): Santana Fossils: An Illustrated Atlas. Tfh Publications Inc. pp. 99–103. ISBN 0866225498.

- Martill, David M.; Bechly, Günter; Loveridge, Robert F. (2007). The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-139-46776-6. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Martill, D.M (2007). "The age of the Cretaceous Santana Formation fossil Konservat Lagerstätte of north-east Brazil: a historical review and an appraisal of the biochronostratigraphic utility of its palaeobiota". Cretaceous Research. 28 (6): 895–920. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2007.01.002. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Weishampel, David B.; et al. (2004). Dinosaur distribution (Early Cretaceous, South America) in: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 563–570. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

Further reading

- David M. Martill, 1993. Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil (Field Guide to Fossils no. 5) (The Palaeontological Association) ISBN 0-901702-46-3

- Neumann, V.H.; Borrego, A.G.; Cabrera, L.; Dino, R. (2003). "Organic matter composition and distribution through the Aptian–Albian lacustrine sequences of the Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil". International Journal of Coal Geology. 54 (1–2): 21–40. doi:10.1016/S0166-5162(03)00018-1. doi:10.1016/S0166-5162(03)00018-1

- Pinheiro, Allysson P.; Saraiva, Antônio Á.; Santana, William (2014). "Shrimps from the Santana Group (Cretaceous: Albian): new species (Crustacea: Decapoda: Dendrobranchiata) and new record (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea)". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 86 (2): 663–670. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420130338. PMID 24789213. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201420130338 PMID 24789213 ISSN 0001-3765

- "Pterosaurs Diorama Depicts Ancient Brazilian Coast". American Museum of Natural History. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2019.