Rosslyn Chapel

Rosslyn Chapel, formerly known as the Collegiate Chapel of St Matthew, is a 15th-century chapel located in the village of Roslin, Midlothian, Scotland.

| Rosslyn Chapel | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) Rosslyn Chapel, August 2014 | |

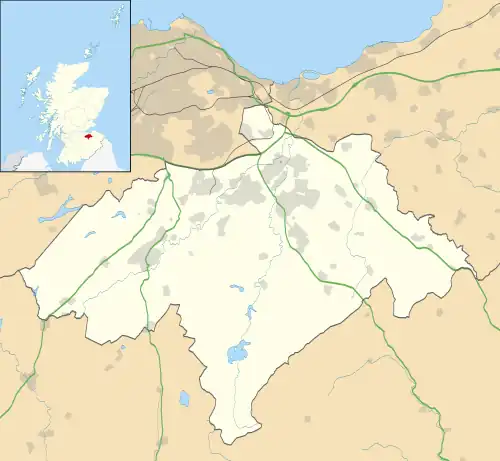

Rosslyn Chapel Shown within Midlothian | |

| 55°51′19″N 3°09′37″W | |

| OS grid reference | NT275630 |

| Location | Roslin, Midlothian |

| Country | Scotland |

| Denomination | Scottish Episcopal Church |

| Previous denomination | Catholic |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Chapel |

| Dedication | Saint Matthew |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Category A |

| Groundbreaking | 20 September 1456 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Edinburgh |

| Clergy | |

| Priest in charge | The Revd Dr Joe Roulston |

Listed Building – Category A | |

| Official name | Rosslyn Chapel (Episcopal), formerly Collegiate Church of St Matthew, including vaults, burial ground and boundary hills |

| Designated | 22 January 1971 |

| Reference no. | 13028[1] |

Rosslyn Chapel was founded on a small hill above Roslin Glen as a Catholic collegiate church (with between four and six ordained canons and two boy choristers) in the mid-15th century. The chapel was founded by William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness of the Scoto-Norman Sinclair family. Rosslyn Chapel is the third Sinclair place of worship at Roslin, the first being in Roslin Castle and the second (whose crumbling buttresses can still be seen today) in what is now Roslin Cemetery.[2]

Sinclair founded the college to celebrate the Divine Office throughout the day and night, and also to celebrate Masses for all the faithful departed, including the deceased members of the Sinclair family. During this period, the rich heritage of plainsong (a single melodic line) or polyphony (vocal harmony) were used to enrich the singing of the liturgy. Sinclair provided an endowment to pay for the support of the priests and choristers in perpetuity. The priests also had parochial responsibilities.

After the Scottish Reformation (1560), Catholic worship in the chapel was brought to an end. The Sinclair family continued to be Catholics until the early 18th century. Of note, while the Sinclair (surname) has its origins in Scotland, it is actually a derivation of the French surname de Saint-Clair.

From the early 1700s to 1861, the chapel was closed to public worship. It was then reopened as a place of worship according to the rites of the Scottish Episcopal Church, a member church of the Anglican Communion.

The chapel was the target of a terrorist bombing in 1914, when a suffragette bomb exploded inside the building during the suffragette bombing and arson campaign.

Since the late 1980s, the chapel has been the subject of speculative theories concerning a connection with the Knights Templar and the Holy Grail, and Freemasonry. It was prominently featured in this role in Dan Brown's bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code (2003) and its 2006 film adaptation. Medieval historians say these accounts have no basis in fact.

Rosslyn Chapel remains privately owned. The current owner is Peter St Clair-Erskine, 7th Earl of Rosslyn.[3]

Architecture

The original plans for Rosslyn have never been found or recorded, so it is open to speculation whether or not the chapel was intended to be built in its current layout. Its architecture is considered to be among the finest in Scotland.[4]

Construction of the chapel began on 20 September 1456, although it has often been recorded as 1446. The confusion over the building date comes from the chapel's receiving its founding charter to build a collegiate chapel in 1446 from Rome. Sinclair did not start to build the chapel until he had built houses for his craftsmen.

Although the original building was to be cruciform, it was never completed. Only the choir was constructed, with the retro-chapel, otherwise called the Lady chapel, built on the much earlier crypt (Lower Chapel) believed to form part of an earlier castle. The foundations of the unbuilt nave and transepts stretching to a distance of 90 feet were recorded in the 19th century. The decorative carving was executed over a forty-year period. After the founder's death, construction of the planned nave and transepts was abandoned - either from lack of funds, lack of interest or a change in liturgical fashion.

The Lower Chapel (also known as the crypt or sacristy) should not be confused with the burial vaults that lie underneath Rosslyn Chapel.[2]

The chapel stands on fourteen pillars, which form an arcade of twelve pointed arches on three sides of the nave. At the east end, a fourteenth pillar between the penultimate pair form a three-pillared division between the nave and the Lady chapel.[5] The three pillars at the east end of the chapel are named, from north to south: the Master Pillar, the Journeyman Pillar and, most famously, the Apprentice Pillar. These names for the pillars date from the late Georgian period — prior to this period they were called the Earl's Pillar, the Shekinah and the Prince's Pillar.

Apprentice pillar

One of the more notable architectural features of the chapel is the "Apprentice Pillar, or "Prentice Pillar". Originally called the "Prince's Pillar" (in the 1778 document An Account of the Chapel of Roslin)[6] the name morphed over time due to a legend dating from the 18th century, involving the master mason in charge of the stonework in the chapel and his young apprentice mason. According to the legend, the master mason did not believe that the apprentice could perform the complicated task of carving the column without seeing the original which formed the inspiration for the design.

The master mason travelled to see the original himself, but upon his return was enraged to find that the upstart apprentice had completed the column by himself. In a fit of jealous anger, the master mason took his mallet and struck the apprentice on the head, killing him. The legend concludes that as punishment for his crime, the master mason's face was carved into the opposite corner to forever gaze upon his apprentice's pillar.[7] There is, however, no evidence that any such murder took place.

On the architrave joining the pillar there is an inscription, Forte est vinum fortior est rex fortiores sunt mulieres super omnia vincit veritas: "Wine is strong, a king is stronger, women are stronger still, but truth conquers all" (1 Esdras, chapters 3 & 4).

The author Henning Klovekorn has proposed that the pillar is representative of one of the roots of the Nordic Yggdrasil tree, prominent in Germanic and Norse mythology. He compares the dragons at the base of the pillar to the dragons found eating away at the base of the Yggdrasil root and, pointing out that at the top of the pillar is carved tree foliage, argues that the Nordic/Viking association is plausible considering the many auxiliary references in the chapel to Celtic and Norse mythology.[8] The general form of the pillar has been related to a type described by the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as a "bunch of sausages."[9]

A full-size plaster cast of the Apprentice Pillar and the adjacent bay of the chapel was made in 1871, and is in the Cast Courts of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[10]

Carvings

Among Rosslyn's many intricate carvings are a sequence of 213 cubes or "boxes" protruding from pillars and arches with a selection of patterns on them. It is unknown if these patterns have any particular meaning attached to them. Many people have attempted to find information coded into them, but no interpretation has yet proven conclusive. Unfortunately, many of these 'boxes' are not original, having been replaced in the 19th century after erosion damage.

One recent attempt to make sense of the boxes has been to interpret them as a musical score. The motifs on the boxes somewhat resemble geometric patterns seen in the study of cymatics. The patterns are formed by placing powder upon a flat surface and vibrating the surface at different frequencies. By matching these Chladni patterns with musical notes corresponding to the same frequencies, the father-and-son team of Thomas and Stuart Mitchell produced a tune which Stuart calls the Rosslyn Motet.[11][12]

There are more than 110 carvings of "Green Men" in and around the chapel. Green Men are carvings of human faces with greenery all around them, often growing out of their mouths. They are found in all areas of the chapel, with one example in the Lady chapel, between the two middle altars of the east wall.

Other carvings represent plants, including depictions of wheat, strawberries or lilies.[13] The authors Robert Lomas and Christopher Knight have hypothesised that some carvings in the chapel represent ears of new world corn or maize, a plant which was unknown in Europe at the time of the chapel's construction. Knight and Lomas view these carvings as evidence supporting the idea that Henry I Sinclair, Earl of Orkney, travelled to the Americas well before Columbus.[14] In their book they discuss meeting with the wife of botanist Adrian Dyer, and that Dyer's wife told him that Dyer agreed that the image thought to be maize was accurate.[14] In fact, Dyer found only one identifiable plant among the botanical carvings and suggested that the "maize" and "aloe" were stylised wooden patterns, only coincidentally looking like real plants.[15]

Crypt

The chapel has been a burial place for several generations of the Sinclairs; a crypt was once accessible from a descending stair at the rear of the chapel. This crypt has been sealed shut for many years, which may explain the recurrent legends that it is merely a front to a more extensive subterranean vault containing (variously) the mummified head of Jesus Christ,[16] the Holy Grail,[17] the treasure of the Templars,[18] or the original crown jewels of Scotland.[19]

In 1837, when the 2nd Earl of Rosslyn died, his wish was to be buried in the original vault. Exhaustive searches over the period of a week were made, but no entrance to the original vault was found and he was buried beside his wife in the Lady Chapel.[20]

Rooftop pinnacle

The pinnacles on the rooftop have been subject to interest during renovation work in 2010. Nesting jackdaws had made the pinnacles unstable and as such had to be dismantled brick by brick revealing the existence of a chamber specifically made by the stonemasons to harbour bees. The hive, now abandoned, has been sent to local bee keepers to identify.[21]

Burials

- William Alexander (1690-1761) Lord Provost of Edinburgh, outside to north-east

- Sir William Alexander (d.1842) outside, to north-east

- Sheila Chisholm (1895–1969), Australian socialite and "it girl" in British high society during and after World War I,[22] who was the mother of Anthony St Clair-Erskine, 6th Earl of Rosslyn

- William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness (in the choir)

- James St Clair-Erskine, 3rd Earl of Rosslyn

- James St Clair-Erskine, 2nd Earl of Rosslyn (in the Lady Chapel)

- Lady Angela St Clair-Erskine, daughter of the 4th Earl.

1914 terrorist bombing

The chapel was the subject of a terrorist attack on 11 July 1914, when a bomb exploded inside the building.[23][24] This was as part of the suffragette bombing and arson campaign of 1912–1914, in which suffragettes carried out a series of politically motivated bombing and arson attacks nationwide as part of their campaign for women's suffrage.[25] Churches were a particular target during the campaign, as it was believed that the Church of England was complicit in reinforcing opposition to women's suffrage.[26] Between 1913 and 1914, 32 churches were attacked nationwide.[27] In the weeks leading up to the attack, there were also bombings at Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral.[25]

Restoration, conservation and tourism

.jpg.webp)

The chapel's altars were destroyed in 1592,[28] and the chapel was abandoned, gradually falling into decay.

In 1842 the chapel, then in a ruined and overgrown state, was visited by Queen Victoria, who expressed a desire that it should be preserved. Restoration work was carried out in 1862 by David Bryce on behalf of James Alexander, 3rd Earl of Rosslyn. The chapel was rededicated on 22 April 1862, and from this time, Sunday services were once again held, now under the jurisdiction of the Scottish Episcopal Church, for the first time in 270 years.

The Rosslyn Chapel Trust was established in 1995, with the purpose of overseeing its conservation and its opening as a sightseeing destination. The chapel underwent an extensive programme of conservation between 1997 and 2013. This included work to the roof, the stone, the carvings, the stained glass and the organ.[29] A steel canopy was erected over the chapel roof for fourteen years. This was to prevent further rain damage to the church and also to give it a chance to dry out properly. Three human skeletons were found during the restoration.[30] Major stonework repairs were completed by the end of 2011. The last major scaffolding was removed in August 2010.[31]

A new visitor centre opened in July 2011. The chapel's stained-glass windows and organ were fully restored. New lighting and heating were installed.[31] The expected cost of the restoration work is around £13 million, with about £3.7 million being spent on the Visitor Centre. Funding has come from various sources including Heritage Lottery Fund, Historic Scotland and the environmental body, WREN. Actor Tom Hanks also made a donation.[31]

Photography and video have been forbidden in the chapel since 2008. The chapel sells commercially produced photos in its shop.[32] In 2006, historian Louise Yeoman criticised the Rosslyn Chapel trust for "cashing in" on the popularity of The Da Vinci Code, against better knowledge.[33]

In the financial year of 2013–14, Rosslyn Chapel recorded 144,823 visitors, the highest number since 2007–08, when (at the height of popular interest induced by The Da Vinci Code), the number of visitors was close to 159,000.[34]

In popular culture

Templar and Masonic connections

The chapel became the subject of speculation regarding its supposed connection with the Knights Templar or Freemasonry beginning in the 1980s.[35] This part of its history was referenced in the DC Comics storyline Batman: Scottish Connection, in which the hero Batman becomes caught up in an old vendetta between two Scottish clans during a visit to Scotland, this mystery including the discovery of an ancient treasure trove hidden in Rosslyn.[36]

The topic entered mainstream pop culture with Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code (2003), reinforced by the subsequent film of the same name (2006),[37] Numerous books were published after 2003 to cater to the popular interest in supposed connections between Rosslyn Chapel, Freemasonry, the Templars and the Holy Grail generated by Brown's novel.[38]

The chapel, built 150 years after the dissolution of the Knights Templar, supposedly has many Templar symbols, such as the "Two riders on a single horse" that appear on the Knights Templar Seal. William Sinclair 3rd Earl of Orkney, Baron of Roslin and 1st Earl of Caithness, claimed by novelists to be a hereditary Grand Master of the Scottish stonemasons, built Rosslyn Chapel.[39] A later William Sinclair of Roslin became the first Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and, subsequently, several other members of the Sinclair family have held this position.[40]

Robert L. D. Cooper, curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland Museum and Library, in 2003 published a 12th edition of the 1892 Illustrated Guide to Rosslyn Chapel with the intention of countering the "nonsense published about Rosslyn Chapel over the last 15 years or so".[41] Cooper in 2006 also published Rosslyn Hoax? in which he actively debunks this type of speculation at length and in great detail. An example is the comparison of the Rosslyn myth of the Apprentice Pillar with that of the allegorical references to Hiram Abiff in Masonic ritual, and in the process he debunks any similarities between the two. A minute comparison between the Rosslyn Myth and the Masonic allegory can be found in a detailed tabular form in The Rosslyn Hoax?[42]

Cooper further debunks other claims of a connection between carvings within Rosslyn Chapel and Scottish Freemasonry. The suggestion that the Apprentice Pillar is a physical reference to the Entered Apprentice degree of Scottish Freemasonry logically led to the conclusion that the other two pillars (in line south to north with the so-called Apprentice Pillar) represented the Fellow of Craft degree (middle pillar) and the Master Mason's degree (north pillar). This association of three pillars in the east part of Rosslyn Chapel with the three degrees of Scottish Freemasonry is impossible, given the fact that (according to Cooper) the third degree of Freemasonry was invented c.1720 - almost 300 years after Rosslyn Chapel was founded.[43]

The claim that the layout of Rosslyn Chapel echoes that of Solomon's Temple[39] has been analysed by Mark Oxbrow and Ian Robertson in their book, Rosslyn and the Grail:

Rosslyn Chapel bears no more resemblance to Solomon's or Herod's Temple than a house brick does to a paperback book. If you superimpose the floor plans of Rosslyn Chapel and either Solomon's or Herod's Temple, you will actually find that they are not even remotely similar. Writers admit that the chapel is far smaller than either of the temples. They freely scale the plans up or down in an attempt to fit them together. What they actually find are no significant similarities at all. [...] If you superimpose the floor plans of Rosslyn Chapel and the East Quire of Glasgow Cathedral you will find a startling match: the four walls of both buildings fit precisely. The East Quire of Glasgow is larger than Rosslyn, but the designs of these two medieval Scottish buildings are virtually identical. They both have the same number of windows and the same number of pillars in the same configuration. [...] The similarity between Rosslyn Chapel and Glasgow's East Quire is well established. Andrew Kemp noted that 'the entire plan of this Chapel corresponds to a large extent with the choir of Glasgow Cathedral' as far back as 1877 in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries. Many alternative history writers are well aware of this but fail to mention it in their books.[13]

As to a possible connection between the St. Clairs and the Knights Templar, the family testified against the Templars when that Order was put on trial in Edinburgh in 1309.[13] Historian Dr. Louise Yeoman, along with other medieval scholars, says the Knights Templar connection is false, and points out that Rosslyn Chapel was built by William Sinclair so that Mass could be said for the souls of his family.[44]

It is also claimed that other carvings in the chapel reflect Masonic imagery, such as the way that hands are placed in various figures. One carving may show a blindfolded man being led forward with a noose around his neck. The carving has been eroded by time and pollution and is difficult to make out clearly. The chapel was built in the 15th century, and the earliest records of freemasonic lodges date back only to the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[45] A more likely explanation, however, is that the Masonic imagery was added at a later date. This may have taken place in the 1860s when James St Clair-Erskine, 3rd Earl of Rosslyn instructed Edinburgh architect David Bryce, a known Freemason, to undertake restoration work on areas of the church including many of the carvings.[46]

Alternative histories

Alternative histories involving Rosslyn Chapel and the Sinclairs have been published by Andrew Sinclair and Tim Wallace-Murphy arguing links with the Knights Templar and the supposed descendants of Jesus Christ. The books in particular by Tim Wallace-Murphy and Marilyn Hopkins Rex Deus: The True Mystery of Rennes-le-Château and the Dynasty of Jesus (2000) and Custodians of Truth: The Continuance of Rex Deus (2005) have focused on the hypothetical Jesus bloodline with the Sinclairs and Rosslyn Chapel.

On the ABC documentary Jesus, Mary and Da Vinci, aired on 3 November 2003, Niven Sinclair hinted that the descendants of Jesus Christ existed within the Sinclair families. These alternative histories are relatively modern - not dating back before the early 1990s. The precursor to these Rosslyn theories is the 1982 book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (retitled Holy Blood, Holy Grail in the United States) by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln that introduced the theory of the Jesus bloodline in relation to the Priory of Sion hoax - the main protagonist of which was Pierre Plantard, who for a time adopted the name Pierre Plantard de Saint-Clair.

See also

References

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Rosslyn Chapel (LB13028)". Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Turnbull, Michael, 'Rosslyn Chapel Revealed' (Sutton Publishing Ltd., November 2007) ISBN 0-7509-4467-6 ISBN 978-0750944670

- "About Rosslyn Chapel". RosslynChapel.org.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 66.

- Wallace-Murphy, Tim; Hopkins, Marilyn. Rosslyn: Guardians of the Secrets of the Holy Grail, Element Books, 1999, p. 8, ISBN 1-86204-493-7.

- Forbes, Robert An Account of the Chapel of Roslin. (reprint ed. Cooper, Robert L. D., Grand Lodge of Scotland, 2000. ISBN 0-902324-61-6)

- Dr Forbes, Bishop of Caithness, An Account of the Chapel of Rosslyn, 1774; cited in Rosslyn Chapel (1997) by the Earl of Rosslyn, p. 27.

- Klovekorn, Henning. The 99 Degrees of Freemasonry. Cornerstone, 2007 ISBN 1-887560-82-3.

- Finlay, Ian, Scottish Crafts, Harrap (1948), p. 23, "On en voit un (pilier) composé de gros boudins en spirale dans l'église de Sainte-Croix de Provins," Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire Raisonné de l’Architecture Française du XIe au XVIe siècle/Pilier

- "Casts in Focus: Rosslyn Chapel". vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Mitchell, Thomas (2006). Rosslyn Chapel: The Music of the Cubes. Diversions Books. ISBN 0-9554629-0-8.

- "Tune into the Da Vinci coda". The Scotsman. 26 April 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Oxbrow, Mark; Robertson, Ian (2005). Rosslyn and the Grail. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84596-076-9.

- Knight, Christopher; Lomas, Robert. The Hiram Key. Fair Winds Press, 2001 ISBN 1-931412-75-8.

- Turnbull, Michael TRB (6 August 2009). "Rosslyn Chapel". BBC. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Laidler, Keith, The Head of God – The Lost Treasure of the Templars (1998).

- Wallace-Murphy, Tim; Hopkins, Marilyn, Rosslyn: Guardian of Secrets of the Holy Grail (1999).

- Robert Lomas, The Origins of Freemasonry

- Ralls-MacLeod, Karen; Robertson, Ian, The Quest for the Celtic Key (2002).

- Donaldson's Guide to Rosslyn Chapel published 1862.

- "Rosslyn Chapel was haven for bees". BBC News. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Walker, Ruth (1 February 2014). "Remarkable journey of Margaret Sheila Mackellar". The Scotsman. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- Metcalfe, Agnes Edith (1917). Woman's Effort: A Chronicle of British Women's Fifty Years' Struggle for Citizenship (1865-1914). B. H. Blackwell. p. 317.

- "Suffragette bombings – City of London Corporation". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- "Suffragettes, violence and militancy". British Library. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Pen and Sword. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5.

- Bearman, C. J. (2005). "An Examination of Suffragette Violence". The English Historical Review. 120 (486): 378. doi:10.1093/ehr/cei119. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 3490924.

- In 1590, the Presbytery forbade George Ramsay, Minister of Lasswade, from burying the wife of Oliver St. Clair in the chapel. The same St. Clair had been repeatedly asked to destroy the chapel's altars because they were taken to represent "monuments of idolatry". St. Clair's tenants were forced to attend the Lasswade Parish Church. In 1592, St. Clair, who had until then refused to destroy the altars, was summoned to appear before the Church of Scotland General Assembly and threatened with excommunication if the altars remained standing after 17 August 1592. On 31 August 1592, George Ramsay reported that the altars of Roslene were haille demolishit. John Charles Carrick, The Abbey of S. Mary, Newbottle: a memorial of the royal visit, 1907, G. Lewis & Co., 1908, p. 153.

- "The Chapel Today". rosslynchapel.org.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Rosslyn Chapel remains reburied in grounds". heraldscotland.com. 16 November 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- "Rosslyn Chapel's resurrection revealed". The Scotsman. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- "Rosslyn Chapel - FAQs". Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "What really upsets me is that they know the Knights Templar connection is false, yet they still perpetuate the myth on their interpretation boards." "Historian attacks Rosslyn Chapel for 'cashing in on Da Vinci Code'". The Scotsman. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- "Scaffolding coming down helps visitor numbers go up". www.rosslynchapel.com (Press release). Rosslyn Chapel Trust. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982), Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry Hardcover John J. Robinson, Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry Hardcover (1989), Michael Baigent The Temple and the Lodge (1991), Coppens, Philip. The Stone Puzzle of Rosslyn Chapel. Frontier Publishing/Adventures Unlimited Press (2002).

- Batman: Scottish Connection by Alan Grant and Frank Quitely, September 1998

- "Hollywood legend Tom Hanks makes donation to Rosslyn Chapel restoration". The Scotsman. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- e.g.: Mark Oxbrow and Ian Robertson, Rosslyn and The Grail. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing (2005), Ashley Cowie. The Rosslyn Templar (2009), Alan Butler and John Ritchie, Rosslyn Revealed, A Library in Stone (2006), Alan Butler and John Ritchie, Rosslyn Chapel Decoded: New Interpretations of a Gothic Enigma (2013).

- Burstein, Dan (2004). Secrets of the Code: The Unauthorized Guide to the Mysteries Behind the Da Vinci Code, p. 248. CDS Books. ISBN 1-59315-022-9.

- National Geographic Channel. Knights Templar, 22 February 2006 video documentary. Written by Jesse Evans.

- "Book Review" at the Grand Lodge of Scotland website: "There has been so much nonsense published about Rosslyn Chapel over the last 15 years or so that it is now extremely difficult to know what is nonsense and what is accurate."

- Robert L D Cooper, The Rosslyn Hoax?, Lewis Masonic 2006, pp. 173–4

- Robert L D Cooper, The Rosslyn Hoax?, Lewis Masonic 2006, pp. 146–7

- "Historian attacks Rosslyn Chapel for 'cashing in on Da Vinci Code'". The Scotsman. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- History page from the website of the United Grand Lodge of England

- "The St Clair Family". rosslynchapel.org.uk. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

Further reading

- Cooper, Robert L. D. The Rosslyn Hoax?. Lewis Masonic. 2006. ISBN 0-85318-255-8.

- Forbes, Robert An Account of the Chapel of Roslin. (reprint ed. Cooper, Robert L. D., Grand Lodge of Scotland, 2000. ISBN 0-902324-61-6).

- Hay, Richard Augustin, Genealogie of the Sainteclaires of Rosslyn. 1835 (reprint ed. Robert L. D. Cooper, Grand Lodge of Scotland. 2002. ISBN 0-902324-63-2).

- Thompson, John, The Illustrated Guide to Rosslyn Chapel and Castle, Hawthornden &c., 1st ed. 1892 (12th edition, Robert L. D. Cooper (ed.), Masonic Publishing Co. 2003. ISBN 0-9544268-1-9).

- Peter St Clair-Erskine, 7th Earl of Rosslyn, Rosslyn Chapel, Rosslyn Chapel Trust, 1997.

External links

- Official Rosslyn Chapel website

- Congregation website

- Rosslyn Chapel's extraordinary carvings explained at last — an article on Rosslyn's Green Men, and an associated reading of its carvings, from The Scotsman

- QuickTime Virtual Reality Image of Rosslyn Chapel by Jonathan Greet, View 2

- "The Rosslyn Templar", a book about the pastel painting by R T McPherson in 1836 of a "Templar Knight at Roslin Chapel" with new photographs of the Chapel