Order of succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated, such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.[1] This sequence may be regulated through descent or by statute.[1]

Hereditary government form differs from elected government. An established order of succession is the normal way of passing on hereditary positions, and also provides immediate continuity after an unexpected vacancy in cases where office-holders are chosen by election: the office does not have to remain vacant until a successor is elected. In some cases the successor takes up the full role of the previous office-holder, as in the case of the presidency of many countries; in other non-hereditary cases there is not a full succession, but a caretaker chosen by succession criteria assumes some or all of the responsibilities, but not the formal office, of the position. For example, when the position of President of India becomes vacant, the Vice-President of India temporarily carries out the functions of the presidency until a successor is elected; in contrast, when the position of President of the Philippines is vacant, the Vice-President of the Philippines outright assumes the presidency itself for the rest of the term.

Organizations without hereditary or statutory order of succession require succession planning if power struggles prompted by power vacuums are to be avoided.

Overview

It is often the case that the inheritance of a hereditary title, office or the like, is indivisible: when the previous holder ceases to hold the title, it is inherited by a single individual. Many titles and offices are not hereditary (such as democratic state offices) and they are subject to different rules of succession.

A hereditary line of succession may be limited to heirs of the body, or may also pass to collateral lines, if there are no heirs of the body, depending on the succession rules. These concepts are in use in English inheritance law.

The rules may stipulate that eligible heirs are heirs male or heirs general – see further primogeniture (agnatic, cognatic, and also equal).

Certain types of property pass to a descendant or relative of the original holder, recipient or grantee according to a fixed order of kinship. Upon the death of the grantee, a designated inheritance such as a peerage, or a monarchy, passes automatically to that living, legitimate, non-adoptive relative of the grantee who is most senior in descent (i.e. highest in the line of succession, regardless of age); and thereafter continues to pass to subsequent successors of the grantee, according to the same rules, upon the death of each subsequent heir.

Each person who inherits according to these rules is considered an heir at law of the grantee and the inheritance may not pass to someone who is not a natural, lawful descendant or relative of the grantee.

Collateral relatives, who share some or all of the grantee's ancestry, but do not directly descend from the grantee, may inherit if there is no limitation to "heirs of the body".

There are other kinds of inheritance rules if the heritage can be divided: heirs portioners and partible inheritance.

Monarchies and nobility

In hereditary monarchies the order of succession determines who becomes the new monarch when the incumbent sovereign dies or otherwise vacates the throne. Such orders of succession, derived from rules established by law or tradition, usually specify an order of seniority, which is applied to indicate which relative of the previous monarch, or other person, has the strongest claim to assume the throne when the vacancy occurs.

Often, the line of succession is restricted to persons of the blood royal (but see morganatic marriage), that is, to those legally recognized as born into or descended from the reigning dynasty or a previous sovereign. The persons in line to succeed to the throne are called "dynasts". Constitutions, statutes, house laws, and norms may regulate the sequence and eligibility of potential successors to the throne.

Historically, the order of succession was sometimes superseded or reinforced by the coronation of a selected heir as co-monarch during the life of the reigning monarch. Examples are Henry the Young King and the heirs of elective monarchies, such as the use of the title King of the Romans for the Habsburg emperors. In the partially elective system of tanistry, the heir or tanist was elected from the qualified males of the royal family. Different monarchies use different rules to determine the line of succession.

Hereditary monarchies have used a variety of methods and algorithms to derive the order of succession among possible candidates related by blood or marriage. An advantage of employing such rules is that dynasts may, from early youth, receive grooming, education, protection, resources and retainers suitable for the future dignity and responsibilities associated with the crown of a particular nation or people. Such systems may also enhance political stability by establishing clear, public expectations about the sequence of rulers, potentially reducing competition and channeling cadets into other roles or endeavors.

Some hereditary monarchies have had unique selection processes, particularly upon the accession of a new dynasty. Imperial France established male primogeniture within the descent of Napoleon I, but failing male issue the constitution allowed the emperors to choose who among their brothers or nephews would follow them upon the throne. The Kingdom of Italy was designated a secundogeniture for the second surviving son of Napoleon I Bonaparte but, failing such, provided for the emperor's stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, to succeed, even though the latter had no blood relationship to the House of Bonaparte. Serbia's monarchy was hereditary by primogeniture for male descendants in the male line of Prince Alexander I, but upon extinction of that line, the reigning king could choose any among his male relatives of the House of Karađorđević. In Romania, on the other hand, upon extinction of the male line descended from Carol I of Romania, the constitution stipulated that the male line of his brother, Leopold, Prince of Hohenzollern, would inherit the throne and, failing other male line issue of that family, a prince of a "Western European" dynasty was to be chosen by the Romanian king and parliament. By contrast, older European monarchies tended to rely upon succession criteria that only called to the throne descendants of past monarchs according to fixed rules rooted in one or another pattern of laws or traditions.

Vertical inheritance

In hereditary succession, the heir is automatically determined by pre-defined rules and principles. It can be further subdivided into horizontal and vertical methods, the former favoring siblings, whereas vertical favors children and grandchildren of the holder.

Primogeniture

In primogeniture (or more precisely male primogeniture), the monarch's eldest son and his descendants take precedence over his siblings and their descendants. Elder sons take precedence over younger sons, but all sons take precedence over daughters. Children represent their deceased ancestors, and the senior line of descent always takes precedence over the junior line, within each gender. The right of succession belongs to the eldest son of the reigning sovereign (see heir apparent), and next to the eldest son of the eldest son. This is the system in Spain and Monaco, and was the system used in the Commonwealth realms for those born before 2011.

Fiefs or titles granted "in tail general" or to "heirs general" follow this system for sons, but daughters are considered equal co-heirs to each other, at least in recent British practice. This can result in the condition known as abeyance. In the medieval period, actual practice varied with local custom. While women could inherit manors, power was usually exercised by their husbands (jure uxoris) or their sons (jure matris).

Absolute cognatic primogeniture

Absolute primogeniture is a law in which the eldest child of the sovereign succeeds to the throne, regardless of gender, and females (and their descendants) enjoy the same right of succession as males. This is currently the system in Sweden (since 1980), the Netherlands (since 1983), Norway (since 1990), Belgium (since 1991), Denmark (since 2009),[2] Luxembourg (since 2011),[3] and in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth realms (since 2013).[4][5][6]

Agnatic-cognatic succession

Agnatic-cognatic (or semi-Salic) succession, prevalent in much of Europe since ancient times, is the restriction of succession to those descended from or related to a past or current monarch exclusively through the male line of descent: descendants through females were ineligible to inherit unless no males of the patrilineage remained alive.

In this form of succession, the succession is reserved first to all the male dynastic descendants of all the eligible branches by order of primogeniture, then upon total extinction of these male descendants to a female member of the dynasty.[7] The only current monarchy that operated under semi-Salic law until recently is Luxembourg, which changed to absolute primogeniture in 2011. Former monarchies that operated under semi-Salic law included Austria (later Austria-Hungary), Bavaria, Hanover, Württemberg, Russia, Saxony, Tuscany, and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

If a female descendant should take the throne, she will not necessarily be the senior heiress by primogeniture, but usually the nearest relative to the last male monarch of the dynasty by proximity of blood. Examples are Christian I of Denmark's succession to Schleswig-Holstein, Maria Theresa of Austria (although her right ultimately was confirmed in consequence of her victory in the War of the Austrian Succession launched over her accession), Marie-Adelaide and Charlotte of Luxembourg, Anne of Brittany, as well as Christian IX of Denmark's succession in the right of his wife, Louise of Hesse.

Matrilineal succession

Some cultures pass honours down through the female line. A man's wealth and title are inherited by his sister's children, and his children receive their inheritance from their maternal uncles.

In Kerala, southern India, this custom is known as Marumakkathayam. It is practiced by the Nair nobility and royal families. The Maharajah of Travancore is therefore succeeded by his sister's son, and his own son receives a courtesy title but has no place in the line of succession. Since Indian Independence and the passing of several acts such as the Hindu Succession Act (1956), this form of inheritance is no longer recognised by law. Regardless, the pretender to the Travancore throne is still determined by matrilinear succession.

The Akans of Ghana and the Ivory Coast, West Africa have similar matrilineal succession and as such Otumfour Osei-Tutu II, Asantehene inherited the Golden Stool (the throne) through his mother (the Asantehemaa) Nana Afia Kobi Serwaa Ampem II.

Salic law

The Salic law, or agnatic succession, restricted the pool of potential heirs to males of the patrilineage, and altogether excluded females of the dynasty and their descendants from the succession. The Salic law applied to the former royal or imperial houses of Albania, France, Italy, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Prussia/German Empire. It currently applies to the house of Liechtenstein, and the Chrysanthemum Throne of Japan.

In 1830 in Spain the question whether or not the Salic law applied – and therefore, whether Ferdinand VII should be followed by his daughter Isabella or by his brother Charles – led to a series of civil wars and the formation of a pretender rival dynasty which still exists.

Generally, hereditary monarchies that operate under the Salic law also use primogeniture among male descendants in the male line to determine the rightful successor, although in earlier history agnatic seniority was more usual than primogeniture. Fiefs and titles granted "in tail male" or to "heirs male" follow this primogenitural form of succession. (Those granted to "heirs male of the body" are limited to the male-line descendants of the grantee; those to "heirs male general" may be inherited, after the extinction of the grantee's male-line descendants, by the male-line descendants of his father, paternal grandfather, etc.)

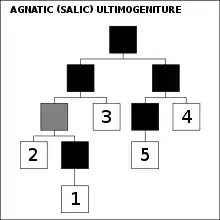

Ultimogeniture

Ultimogeniture is an order of succession where the subject is succeeded by the youngest son (or youngest child). This serves the circumstances where the youngest is "keeping the hearth", taking care of the parents and continuing at home, whereas elder children have had time to succeed "out in the world" and provide for themselves.

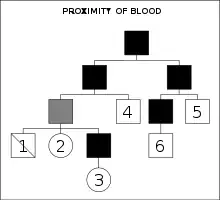

Proximity of blood

Proximity of blood is a system wherein the person closest in degree of kinship to the sovereign succeeds, preferring males over females and elder over younger siblings. This is sometimes used as a gloss for "pragmatic" successions in Europe; it had somewhat more standing during the Middle Ages everywhere in Europe. In Outremer it was often used to choose regents, and it figured in some of the succession disputes over the Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was also recognized in that kingdom for the succession of fiefs, under special circumstances: if a fief was lost to the Saracens and subsequently re-conquered, it was to be assigned to the heir in proximity of blood of the last fief-holder.

Partible inheritance

In some societies, a monarchy or a fief was inherited in a way that all entitled heirs had a right to a share of it. The most prominent examples of this practice are the multiple divisions of the Frankish Empire under the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, and similarly Gavelkind in the British Isles.

Horizontal inheritance

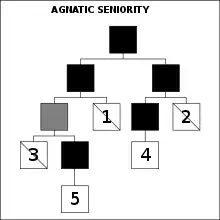

Seniority

In seniority successions, a monarch's or fiefholder's next sibling (almost always brother), succeeds; not his children. And, if the royal house is more extensive, (male) cousins and so forth succeed, in order of seniority, which may depend upon actual age or upon the seniority between their fathers.

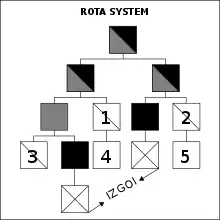

Rota system

The rota system, from the Old Church Slavic word for "ladder" or "staircase", was a system of collateral succession practised (though imperfectly) in Kievan Rus' and later Appanage and early Muscovite Russia.

In this system, the throne passed not linearly from father to son, but laterally from brother to brother and then to the eldest son of the eldest brother who had held the throne. The system was begun by Yaroslav the Wise, who assigned each of his sons a principality based on seniority. When the Grand Prince died, the next most senior prince moved to Kiev and all others moved to the principality next up the ladder.[8]

Tanistry

The Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands.

Elective succession

Appointment, election, tanistry, and rotation

Order of succession can be arranged by appointment: either the incumbent monarch or some electoral body appoints an heir or a list of heirs before vacancy occurs. A monarchy may be generally elective, although in a way that the next holder will be elected only after it becomes vacant.

In history, quite often, but not always, appointments and elections favored, or were limited to, members of a certain dynasty or extended family. There may be genealogical rules to determine all who are entitled to succeed, and who will be favored. This has led sometimes to an order of succession that balances branches of a dynasty by rotation.

It currently applies, with variations, to Andorra, Cambodia, Eswatini, the Holy See, Kuwait, Malaysia, the UAE, and Samoa. It is also used in Ife, Oyo and the other subnational states of the Yorubaland region.

Lateral succession

Lateral or fraternal system of succession mandates principles of seniority among members of a dynasty or dynastic clan, with a purpose of election a best qualified candidate for the leadership. The leaders are elected as being the most mature elders of the clan, already in possession of military power and competence. Fraternal succession is preferred to ensure that mature leaders are in charge, removing a need for regents. The lateral system of succession may or may not exclude male descendants in the female line from succession. In practice, when no male heir is mature enough, a female heir is usually determined "pragmatically", by proximity to the last monarch, like Boariks of the Caucasian Huns or Tamiris of Massagetes in Middle Asia were selected. The lateral monarch is generally elected after the leadership throne becomes vacant. In the early years of the Mongol empire, the death of the ruling monarchs, Genghis Khan and Ögedei Khan, immediately stopped the Mongols' western campaigns because of the upcoming elections.

In East Asia, the lateral succession system is first recorded in the pre-historical period starting with the late Shang dynasty's Wai Bing succeeding his brother Da Ding, and then in connection with a conquest by the Zhou of the Shang, when Wu Ding was succeeded by his brother Zu Geng in 1189 BC and then by another brother Zu Jia in 1178 BC.[9]

A drawback of the lateral succession is that, while ensuring a most competent leadership for the moment, the system inherently created derelict princely lines not eligible for succession. Any scion of an eligible heir who did not live long enough to ascend to the throne was cast aside as not eligible, creating a pool of discontented pretenders called Tegin in Turkic and Izgoi in Rus dynastic lines. The unsettled pool of derelict princes would eventually bring havoc to the succession order and dismemberment to the state.

Succession crises

When a monarch dies without a clear successor, a succession crisis often ensues, frequently resulting in a war of succession. For example, when King Charles IV of France died, the Hundred Years War erupted between Charles' cousin, Philip VI of France, and Charles' nephew, Edward III of England, to determine who would succeed Charles as the King of France. Where the line of succession is clear, it has sometimes happened that a pretender with a weak or spurious claim but military or political power usurps the throne.

In recent years researchers have found significant connections between the types of rules governing succession in monarchies and autocracies and the frequency with which coups or succession crises occur.[10]

Religion

In Tibetan Buddhism, it is believed that the holders of some high offices such as the Dalai Lama are reincarnations of the incumbent: the order of succession is simply that an incumbent is followed by a reincarnation of himself. When an incumbent dies, his successor is sought in the general population by certain criteria considered to indicate that the reincarnated Dalai Lama has been found, a process which typically takes two to four years to find the infant boy.

In the Catholic Church, there are prescribed procedures to be followed in the case of vacancy of the papacy or a bishopric.

Republics

| Part of a series on Orders of succession |

| Presidencies |

|---|

In republics, the requirement to ensure continuity of government at all times has resulted in most offices having some formalized order of succession. In a country with fixed-term elections, the head of state (president) is often succeeded following death, resignation, or impeachment by the vice president, parliament speaker, chancellor, or prime minister, in turn followed by various office holders of the legislative assembly or other government ministers. In many republics, a new election takes place some time after the "presidency" becomes unexpectedly vacant.

In states or provinces within a country, frequently a lieutenant governor or deputy governor is elected to fill a vacancy in the office of the governor.

- Example of succession

- If the President of the United States is unable to serve, the Vice President takes over if able to serve. If not, the order of succession is Speaker of the House, President pro tempore of the Senate, Secretary of State, and other cabinet officials as listed in the article United States presidential line of succession.

- In Finland, the president's temporary successor is the prime minister and then the ministers in the order of days spent in office, instead of in order of ministry. There is no vice president, and a new president has to be elected if the president dies or resigns.

- In Israel, the president's temporary successor is the Speaker of the Knesset (the Israeli parliament), with the new president being elected by the parliament if the president dies or resigns.

See also

Lines of succession of elected office-holders

(Incomplete list)

- Cabinet of Mauritius § Allowances and line of succession

- Governor of Oklahoma § Line of succession

- Presidential Succession Act

- Sede vacante (Catholic popes, archbishops, and bishops)

See also the articles on various offices (e.g., President of the United States § Succession and disability).

References

- UK Royal Web site "The order of succession is the sequence of members of the Royal Family in the order in which they stand in line to the throne. This sequence is regulated not only through descent, but also by Parliamentary statute."

- "Dänemark: Prinzessinnen bekommen gleiche Thron-Chancen" (in German). Spiegel Online. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- New Ducal succession rights for Grand Duchy

- Bloxham, Andy; Kirkup, James (28 October 2011). "Centuries-old rule of primogeniture in Royal Family scrapped". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Explanatory note to the UK bill, paragraph 42: "There is power to specify the time of day of commencement. Assuming that the other Realms make the same provision, this will enable the changes on succession to be brought into force at the same time – but at different local times – in all sixteen Commonwealth Realms." UK parliament official website. (Retrieved 30 March 2015.)

- Professor Anne Twomey (26 March 2015). "Power to the princesses: Australia wraps up succession law changes". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- SOU 1977:5 Kvinnlig tronföljd.

- Nancy Shields Kollmann, "Collateral Succession in Kievan Rus'." Harvard Ukrainian Studies 14 (1990): 377–87; Janet Martin, Medieval Russia 980–1584 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 27–29.

- Loewe M. and Shaughnessy E.L., eds., The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C., New York, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 234, 273, 303, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8

- Kurrild-Klitgaard, Peter (2000). "The constitutional economics of autocratic succession," Public Choice, 103(1/2), pp. 63–84.