Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière

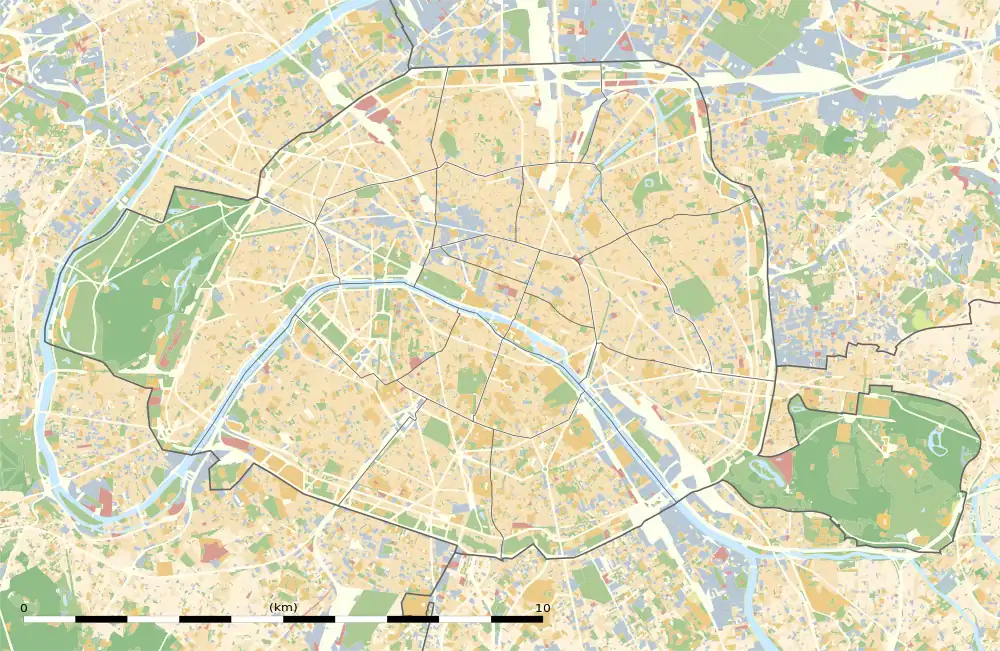

The Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière[1] marks the boundary between the 9th and 10th arrondissements of Paris, the main thoroughfare of the old Faubourg Poissonnière district.

| |

Shown within Paris | |

| Arrondissement | 9th and 10th |

|---|---|

| Quarter | Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Porte-Saint-Denis Rochechouart Faubourg-Montmartre |

| Coordinates | 48°52′36.949″N 2°20′55.878″E |

| From | Boulevard Poissonnière |

| To | Boulevard de Bonne-Nouvelle |

Location and access

Origin of the name

The rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière owes its name to the fact that it crossed the hamlet located outside the porte de la Poissonnerie of the surrounding wall drawn in the alignment of the rue des Poissonniers to the north and the rue Poissonnière to the south, it formed part of the chemin des Poissonniers. The faubourg was originally a district “fors le bourg” (from the old French “fors”, derived from the Latin foris “en dehors” and from borc, “bourg”, forsborc around 1200, forbours around 1260).[2]

History

In the 17th century, the street which appears on the old plans bore the name of “Chaussée de la Nouvelle-France” because it led to the hamlet of Nouvelle-France founded in 1642 on an old vineyard.

It ran along, in its southern part of the boulevard to the large sewer (location since its covering in 1760 of the rue des Petites-Écuries), the seam of the Filles-Dieu which extended to the east to the rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, and, to the north of the rue de Paradis, the Saint-Lazare enclosure which also extended to the east to the faubourg Saint-Laurent.

In 1660, it took the name "rue Sainte-Anne", because of a chapel that had been built there at number 77 to serve the district of New France.[3]

From 1770, Claude-Martin Goupy speculated in the Faubourg Poissonnière on land sold by the community of Filles-Dieu, of which he was the entrepreneur, playing a key role in the urbanization of the district4.

During the Trois Glorieuses, the route was the scene of confrontation between the insurgents and the troops.

On March 8, 1918, during the World War I, a bomb thrown from a German plane exploded at no. 66 rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière.[4]

On April 1, 1918, a shell launched by the Paris Gun exploded at no. 54 rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière.

Remarkable buildings and places of memory

- At No. 2 is Lycée Edgar-Poe.

Lycée Edgar-Poe

Lycée Edgar-Poe

- No 3: location, in the second half of the 19th century, of the Bains du Gymnase, the first Parisian public bath establishment to have been raided by the morality police. The trial of the homosexuals who were arrested there took place in June 1876 (Affaire des Bains du Gymnase[5]) before the Paris Criminal Court.

- No 4: the vaudevillist Nicolas Brazier lived there in 1831.

- No. 5: house where Colonel La Bédoyère was arrested in 1815, at Madame de Fontry's. This number was then occupied by the newspaper Le Matin.

- No 9: Jean-Baptiste Buffault lived there.

- At number 10 was the Alcazar café-concert opened in 18588 and replaced in 1899 by a four-storey commercial building designed by the architects Auguste and Gustave Perret, the first office building built in France.

- At number 13 was the Hôtel de Sénac de Meilhan.

- At no. 15 was the former Hôtel des Menus-Plaisirs du Roi, where his administration was based, in a vast building that stretched from rue Bergère to rue Richer today. During the Revolution, the revolutionary section of Faubourg-Montmartre met there. This is where the Convention set up the Music Conservatory in 1795.

- Nos 15-17: Bergère telephone exchange, also called “Provence”, built in 1911-1914 by the architect François Le Cœur.[6]

- Number 25 was inhabited by Luigi Cherubini during the last years of his life.

- At number 26 was the Hôtel de Cypierre, since destroyed, built by the architect Jean-Benoît-Vincent Barré for Jean-François Perrin de Cypierre.

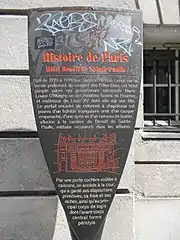

- Classified as a historic monument, no. 30, Hôtel Benoît de Sainte-Paulle, also known as "Hôtel Chéret" or "Akermann" and Hôtel Ney,[7] built by Nicolas Lenoir in 1773 for François Benoît de Sainte-Paulle, on land acquired in 1172 by Claude-Martin Goupy, architect and speculator behind the creation of the district. The two courtyard wings were built in 1778 by Antoine-François Peyre. From 1779 to 1795, this hotel was the property of Marie-Louise O'Murphy, wife of François Nicolas Le Normand de Flaghac. Under the Empire, it belonged to Marshal Ney. In 1942 the design office of the Société anonyme des factories Farman was housed there, which employed the future General Jacques Collombet there that year, as an engineer. The hotel is now occupied by social housing managed by the property management of the city of Paris.[8]

Number 30.

Number 30.

- No 32: entrance to a coach passage leading to a dead end. This set, or city, comes from the subdivision made by the marble sculptor Leprince (apparently François-Robert, from a dynasty of marble workers and wives of marble workers, including François Leprince, marble worker of the king who died in 1746, already installed in the Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle district). The land had been acquired by Claude-Martin Goupy in 1771 by emphyteutic lease from the convent of the Filles-Dieu. In 1772, Goupy ceded his rights to these lands to Leprince, who had buildings built between 1773 and 1776, probably by his brother, on the site of the gardens and the few farmhouses that already existed. The marble worker established his accommodation and probably his workshops on the spot, without it being possible to say whether he was staying on the street, or in one of the two hotels located in the impasse.

- The building on the street (no. 32 bis) was joined to no. 34 during the 19th century to form a large apartment building after complete recovery of the wings of the building at the back of the courtyard. This building was completely separated from the rest of the housing estate, apparently from the end of the 18th century. It is probably Leprince who is the author of the models of the stuccoed panels with antique motifs visible on the street facade of 32 bis, and of which we can see occurrences on various Parisian buildings of the same period. He also probably created the stucco decorations of the same type preserved in the reception rooms of one of the hotels in the passage;

- The first hotel in the passage (no. 32A) is in a "U" shape, backing onto a courtyard, without a garden. It was modified in the middle of the 19th century and then raised by one floor at the beginning of the 21st century, following the style adopted for the lower floors ;

- The back of the Leprince housing estate is occupied by a second hotel accessible under a porch (no. 32, building 1), organized around a courtyard. Oral tradition indicates that the Folies Bergère feather workshop occupied the 1st floor of the hotel during the 20th century. Its outbuildings consisted of a set of wings flat against the northern adjoining areas, up to rue d'Hauteville (building 4 is a remnant of this). These wings housed accommodation and possibly workshops. Before the end of the 18th century, the half facing rue d'Hauteville was separated by building a transverse wing (building 3), thus closing off a second courtyard. Under the Empire (around 1810), the garden of this hotel was replaced by an immovable (building) along the passage, in order to extend the spaces of the initial hotel. This building was separated from Building 1 around 1830 and converted into an independent apartment building, still in the neoclassical style. To replace the wing overlooking the garden, an industrial building (building 5) was built around 1900, between the adjoining building and building 2. The interior of this building was completely transformed in the 1980s and then in 2012-2013. The Cité Leprince is a good example of historical stratification within the framework of the progressive subdivision of the Faubourg Poissonnière between 1770 and 1900.[9]

- Dead end of n° 32

Entrance of the passage.

Entrance of the passage. Private mansion of number 32A.

Private mansion of number 32A. Entrance to the private mansion at the bottom of the Cité Leprince (building 1).

Entrance to the private mansion at the bottom of the Cité Leprince (building 1).

Court at the bottom of the impasse, wings built between 1773 and 1785.

Court at the bottom of the impasse, wings built between 1773 and 1785. View of the passage towards the street, original gate of the Leprince estate, in Louis XVI style.

View of the passage towards the street, original gate of the Leprince estate, in Louis XVI style.

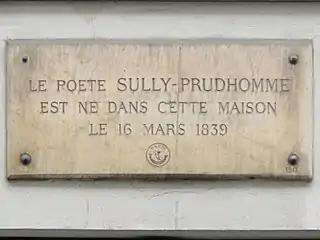

- No 34 : plaque in memory of the poet Sully Prudhomme born in this house on March 16, 1839.

Entry of Number32 bis-34.

Entry of Number32 bis-34. Number34 : commemorative plaque in homage to Sully Prudhomme.

Number34 : commemorative plaque in homage to Sully Prudhomme.

- No 36 : building facade.

Number 36, with passage under building opening onto rue Gabriel-Laumain.

Number 36, with passage under building opening onto rue Gabriel-Laumain.

- No 50: Hotel Cardon built around 1773-1774 by Claude-Martin Goupy for the sculptor and director of the Académie de Saint-Luc, Nicolas-Vincent Cardon.

- No 52: hotel built around 1775 by Claude-Martin Goupy for the painter-decorator Pierre-Hyacinthe Deleuze, of the Academy of Saint-Luc15.

- No 52: Julie Candeille lived there in 1834.

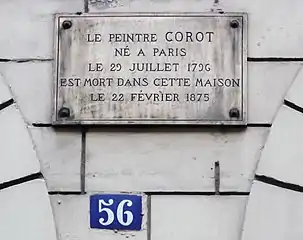

- No 56: plaque in memory of the painter Camille Corot, who died on February 22, 1875 in this house. Here lived in 1833 the painter Alexandre-Charles Sauvageot (1781-1860), who was represented in the dining room of his apartment, in the middle of his collections by his friend Louis-Pierre Henriquel-Dupont, a drawing in 1833 and an engraving of 1852. A painting of the same was also painted by the painter Arthur Henry Roberts in 1857.

The number 56.

The number 56. Number 56 : Camille Corot.

Number 56 : Camille Corot.

- No 57: location of the former Opéra décor store which was destroyed by fire in 1894. The store occupied the site of the former Menus-Plaisirs du Roi stores. At this location, rue Ambroise-Thomas was opened in 1897.

Number 57.

Number 57.

- No 58: former Hôtel Titon built by Jean-Charles Delafosse around 1776.[10]

Number 58.

Number 58.

- No 64 (corner of rue de Paradis): location of the Porte Sainte-Anne built in 1645 and destroyed around 1715. The granting barrier at this location is shown on Turgot's plan. It was replaced around 1788 by the Poissonnière barrier on the Wall of the Ferme générale.

- No 66-68: Gustave Prioré publishing house, musical editions (circa 1850). Gustave Prioré is also a composer.

- No 69-71 (corner rue Bleue): then rue Sainte-Anne, site of the dwelling of the Sanson family, executors of high works of justice. The garden extended beyond the current rue Bleue.[11] After the death of Charles-Henri Samson in 1778, his heirs sold the complex to the architect Nicolas Lenoir who subdivided the land with the opening in 1780 of the streets Papillon, Riboutté and the widening of the rue Bleue (then rue d'Enfer).

- No 72: stay from 1841 to 1846 of Henri Heine (1797-1856). Large plate.

- No 76: location of the first so-called “New France” barracks, built by Claude-Martin Goupy on land he had purchased in 1770 from the monks of Saint-Lazare. From 1773, he rented this barracks by the year to the French Guards. Louis Antoine de Gontaut-Biron, Lazare Hoche (then 17 years old and a soldier) and François Joseph Lefebvre (sergeant in 1789) began their military careers there. An unfounded legend adds the name of Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte.

On July 27, 1830, Captain Flandin, at the head of 200 citizens, of whom there were perhaps not 20 who were armed, attacked this barracks, made 140 young soldiers of the 50th line lay down their arms, and seized this important post, where valuable resources for the defense were found. Infantry troops sat there until 1914, then the Republican Guard. Dilapidated, the building was destroyed around 1930. A new barracks was built at nos. 80-8218.

.jpg.webp) Number 76 : barracks Nouvelle-France.

Number 76 : barracks Nouvelle-France.

- No 77: site of the Sainte-Anne chapel built in 1650, demolished in 1790, where the wife of the executioner Charles Sanson was buried.

- Listed as a historical monument, number 80 was a former pub at the corner of rue des Messageries, with a storefront from the first half of the 19th century, listed as a historical monument.

Number 80 : facade of the ancien débit de boisson.

Number 80 : facade of the ancien débit de boisson.

- Nos 80-82: the new barracks in New France were built between 1932 and 1941 for the city of Paris by the architect Boegner. On the wall of the building located at no. 80 rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière, the sculptures come from the entrance to the first barracks which was located at current no. 76.[12]

- No 88: Gaston Poittevin (1880-1944) lived there in 1941.[13]

- No 92: Étienne Calla, mechanic, pupil of Jacques de Vaucanson, set up a foundry in 1820.[14] It was the Calla firm that produced the ornamental cast iron for the church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul at the request of Jacques Hittorff. The Calla foundry moved north of the Saint-Lazare enclosure, to La Chapelle, in 1849.[15]

- No 98: Boris Vian lived there after his marriage from 1942.

- No 106: Lycée Rocroy-Saint-Léon, private establishment opened in 1877.[16] Before the construction of the high school, Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich lived there in his private mansion, which was subsequently demolished.

- Classified as a historic monument, no. 121, the Lycée Lamartine founded in 1893 on the site of a lustschloss (mansion) dating from the 17th century, bought in 1891 by the National Education. Many works are done, but some parts were kept as they were and classified as historical monuments (office, living room and interior decor).[17]

- No 129: site of the entrance to the first gasworks in Paris. In 1807, François de Neufchâteau bought a house on this site comprising a plot of 1 hectare.[18] In 1821, in debt, he was forced to sell this property. In 1823, Antoine Pauwels built a gasometer there, then Étienne Calla set up a foundry there until 1849.[19]

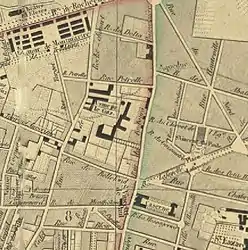

- Faubourg-Poissonnière street gasometer

Location of the future gasometer on rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière in 1814.

Location of the future gasometer on rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière in 1814. Location of the rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière gasometer in 1837.

Location of the rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière gasometer in 1837. Location of the rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière gasometer in 1848.

Location of the rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière gasometer in 1848.

- No 138: location of the Wallart carpentry factory built in 1896 (building also fronting 45, rue de Dunkerque). It was a three-storey building in sculpted wood with mortise and tenon fittings (the workshops were on rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière, the main porch for the passage of trucks opened on rue de Dunkerque), a unique masterpiece of wooden architecture in Paris, which disappeared with the construction in the early 1970s of the apartment building that is there today.

- No 146: headquarters of the Éditions Sociales and the Éditions Messidor as well as the Livre-club Diderot and the Cahiers du communisme.

- No 148: headquarters of the Union of French Women and Clear Hours.

- No. 153: Émile Souvestre lived there.

- Nos. 157 to 187: location of the Promenades egyptiennes, an establishment where parties such as those at the Tivoli amusement park were held. Opened on May 4, 1818, they gave way to the Delta garden, from 1819 to 1824.[20]

- No 161: location of a house where Charles de Bourbon-Condé lived with his mistress Madame de la Saune.

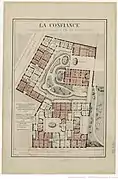

- Nos 171, 173 and 175: buildings on rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière from the building complex built by the insurance company La Confiance in 1880, consisting of six buildings on this road (three on the street, three on the garden), four buildings on rue de Dunkerque (all on the street), and a hotel surrounded by a garden and equipped with outbuildings at the back of the plot.

- The day after August 10, 1792, it was near the Poissonnière barrier, in a vast trench dug for this purpose, that the 400 to 500 corpses of the Swiss Guards killed in the stairs, courtyards and Tuileries garden were thrown pell-mell19.

- On June 23, 1848, the Poissonnière barrier was the subject of fierce fighting between the insurgents, barricaded in the buildings, and the government troops.

Poissonnière Barrier: Days of June, in the Enclos Saint-Lazare

Poissonnière Barrier: Days of June, in the Enclos Saint-Lazare

The 23rd of June 1848. Plan of the real estate complex of Numbers 171, 173 and 175 rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière and the numbers 46, 48 et 50 rue de Dunkerque

Plan of the real estate complex of Numbers 171, 173 and 175 rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière and the numbers 46, 48 et 50 rue de Dunkerque

References

- Nomenclature des voies

- Alain Rey, Dictionnaire historique de la langue française, Le Robert, 2006

- Dictionnaire administratif et historique des rues de Paris et de ses monuments

- Excelsior du 8 janvier 1919 : Carte et liste officielles des bombes d'avions et de zeppelins lancées sur Paris et la banlieue et numérotées suivant leur ordre et leur date de chute

- Perverses promiscuités ? Bains publics et cafés-concerts parisiens au second XIXe siècle

- Central téléphonique «Provence»

- Hôtel Chéret ou Akermann

- Ravalement des façades sur cours et reprise des pans de bois 30-32, rue du Fbg-Poissonnière (10e)

- Pascal Etienne, Le Faubourg Poissonnière. Architecture, élégance et décor, Paris, Délégation à l'Action artistique de la Ville de Paris, 1986, 312 p., p. 30-32

- Maison, ancien hôtel Titon

- Pascal Etienne, Le Faubourg Poissonnière. Architecture, élégance et décor , Paris, Délégation à l'Action artistique de la Ville de Paris , 1986, 312 p., p. 62-66

- Emplacement de la caserne de la Nouvelle France

- Le Petit Parisien : journal quotidien du soir

- Les Rues de Paris. Paris ancien et moderne ; origines, histoire, monuments, costumes, mœurs, chroniques et traditions; ouvrage rédigé par l'élite de la littérature contemporaine sous la direction de Louis Lurine, et illustré de 300 dessins exécutés par les artistes les plus distingués, volume 2

- Histoire de la culture tecHnique et scientifique en Europe (XVie-XiXe siècles)

- Histoire

- Lycée Lamartine

- François DE NEUFCHATEAU

- Guide exposition « Le clos Saint-Lazare »

- POURQUOI LE LOUXOR. DE LA CAMPAGNE D’ÉGYPTE AU JARDIN DU DELTA