Runit Island

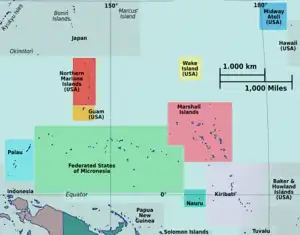

Runit Island (/ˈruːnɪt/) is one of forty islands of the Enewetak Atoll of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean. The island is the site of a radioactive waste repository left by the United States after it conducted a series of nuclear tests on Enewetak Atoll between 1946 and 1958. There are ongoing concerns around deterioration of the waste site and a potential radioactive spill.[1]

Satellite view of Runit Island showing the Runit Dome | |

Runit Island  Runit Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 11°32′42″N 162°21′11″E |

| Archipelago | Enewetak Atoll |

| Total islands | 40 |

| Administration | |

| Capital city | Majuro |

Runit Dome

Construction

The Runit Dome, also called Cactus Dome or locally The Tomb, is a 115 m (377 ft) diameter,[2] 46 cm (18 in) thick dome of concrete at sea level, encapsulating an estimated 73,000 m3 (95,000 cu yd) of radioactive debris, including some plutonium-239. The debris stems from nuclear tests conducted in the Enewetak Atoll by the United States between 1946 and 1958.[3][4]

From 1977 to 1980, loose waste and topsoil from six different islands in the Enewetak Atoll was transported to the site and mixed with concrete to seal the nuclear blast crater created by the Cactus test. Four thousand US servicemen were involved in the cleanup from this test, and it took three years to complete. The waste-filled crater was finally entombed in concrete.[5]

Erosion

In 1982, a US government task force raised concern about a probable breach if a severe typhoon were to hit the island.[6] In 2013, a report by the US Department of Energy[7] found that the concrete dome had weathered with minor cracking of the structure.[8]

However, the soil around the dome was found to be more contaminated than its contents, so a breach could not increase the radiation levels by any means. Because the cleaning operation in the 1970s only removed an estimated 0.8 percent of the total transuranic waste in the Enewetak atoll,[9]: 2 the soil and the lagoon water surrounding the structure now contain a higher level of radioactivity than the debris of the dome itself, so even in the event of a total collapse, the radiation dose delivered to the local resident population or marine environment should not change significantly.

Concern primarily lies in the rapid tidal response to the height of the water beneath the debris pile, with the potential for contamination of the groundwater supply with radionuclides. One particular concern is that, in order to save costs, the original plan to line the porous bottom crater with concrete was abandoned.[3] Since the bottom of the crater consists of permeable soil, there is seawater inside the dome.[3]

However, as the Department of Energy report stated, the released radionuclides will be very rapidly diluted and should not cause any elevated radioactive risk for the marine environment, compared to what is already experienced.[7] Leaking and breaching of the dome could however disperse plutonium, a radioactive element that is also a toxic heavy metal.[10][11]

An investigative report by the Los Angeles Times in November 2019 reignited fears of the dome cracking and releasing radioactive material into the soil and surrounding water.[1][12] The DOE was directed by Congress to assess the condition of the structure and develop a repair plan during the first half of 2020.[13] The report was published in June 2020.[9]

In June 2020, the US Department of Energy released a report stating that the dome is in no immediate danger of collapse or breach and that the radioactive material within is not expected to have any measurable adverse effect on the surrounding environment for the next twenty years.[14]

Illness of army personnel

Some of the US army personnel who participated in the dome construction and transport of radioactive materials claim that illnesses that developed years later are a result of having been exposed without protection. Some of them have died of cancer and others have become sick. The US government denies that there is any connection between the work on the island and the health problems and has so far refused to offer any compensation for the illnesses associated with the construction of Runit Dome.[15]

Gallery

Runit Island, part of the Enewetak Atoll

Runit Island, part of the Enewetak Atoll In 1952, the United States dropped the nuclear bomb Ivy King 610 m (2,000 feet) north of Runit Island.

In 1952, the United States dropped the nuclear bomb Ivy King 610 m (2,000 feet) north of Runit Island. Crater created by detonation on 5 May 1958 (Operation Hardtack I, Cactus test)

Crater created by detonation on 5 May 1958 (Operation Hardtack I, Cactus test)

References

- "How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster". Los Angeles Times. 10 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "A Visual Description of the Concrete Exterior of the Cactus Crater Containment Structure" (PDF). October 2013.

- Willacy, Mark (28 November 2017). "A poison in our island". ABC (Australia). Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- Emma Reynolds. "Deadly dome of gorgeous Pacific island leaking radioactive waste", news.com.au, 7 July 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Enewetak". Marshall Islands Dose Assessment & Radioecology Program. 7 April 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Michael B. Gerrard (3 December 2014). "A Pacific Isle, Radioactive and Forgotten". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- Visual Description of the Concrete Exterior of the Cactus Crater Containment Structure LLNL-TR-648143

- Jan Hendrik Hinzel, Coleen Jose and Kim Wall. "This dome in the Pacific houses tons of radioactive waste – and it's leaking", The Guardian, 3 July 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- "Report on the Status of the Runit Dome in the Marshall Islands" (PDF). Energy.gov. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- Mark Willacy (27 November 2017). "The Dome". ABC (Australia). Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- A Pacific isle radioactive and forgotten, The New York Times, Michael B. Gerrard, 3 December 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Mizokami, Kyle (27 December 2019). "Nuclear Waste – Runit Dome – Marshall Islands". www.popularmechanics.com. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Report on the Status of the Runit Dome in the Marshall Islands" (PDF). energy.gov. June 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- "Troops Who Cleaned Up Radioactive Islands Can't Get Medical Care". The New York Times. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2021.