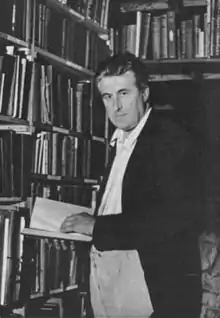

Rupert Gould

Rupert Thomas Gould (16 November 1890 – 5 October 1948) was a lieutenant-commander in the British Royal Navy noted for his contributions to horology (the science and study of timekeeping devices).[1] He was also an author and radio personality.

Rupert Gould | |

|---|---|

Commander R T Gould | |

| Born | Rupert Thomas Gould 16 November 1890 |

| Died | 5 October 1948 (aged 57) Canterbury, Kent, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Author, radio personality |

| Spouse | Muriel Estall |

| Children | Cecil Gould Jocelyne Stacey |

Life

Gould grew up in Southsea, near Portsmouth, where his father, William Monk Gould, was a music teacher, organist, and composer. He was educated at Eastman's Royal Naval Academy[2] and then, from 15 January 1906 the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, being part of the 'Greynville' term (group), and by Easter 1907, examinations placed him at the top of his class. He became a midshipman on 15 May 1907. He initially served on HMS Formidable and HMS Queen (under Captain David Beatty) in the Mediterranean. Subsequently, he was posted to China (first aboard HMS Kinsha and then HMS Bramble). He chose the "navigation" career track and, after qualifying as a navigation officer, served on HMS King George V and HMS Achates until near the outbreak of World War I, at which time he suffered a nervous breakdown and went on medical leave. During his lengthy recuperation, he was stationed at the Hydrographer's Department at the Admiralty, where he became an expert on various aspects of naval history, cartography, and expeditions of the polar regions. In 1919 he was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander (retired).

On 9 June 1917 he married Muriel Estall. That marriage ended by judicial separation in November 1927. They had two children, Cecil (born in 1918) and Jocelyne (born in 1920). His last years were spent at Barford St Martin near Salisbury, where he used his horological skills to repair and restore the defunct clock in the church tower.[3]

Work

He gained permission in 1920 to restore the marine chronometers of John Harrison, and this work was completed in 1933.

His horological book The Marine Chronometer, its history and development was first published in 1923 by J.D. Potter and was the first scholarly monograph on the subject. It was generally considered the authoritative text on marine timekeepers for at least half a century.

Gould had many other interests and activities. In spite of two more nervous breakdowns, he wrote and published an eclectic series of books on topics ranging from horology to the Loch Ness Monster. He was a science educator, giving a series of talks for the BBC's Children's Hour starting in January 1934 under the name "The Stargazer", and these collected talks were later published. He was a member of the BBC radio panel The Brains Trust. He umpired tennis matches on the Centre Court at Wimbledon on many occasions during the 1930s.

In 1947 he was awarded the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, its highest honour for contributions to horology.

Gould died on 5 October 1948 at Canterbury, Kent, from heart failure. He was 57 years of age.

In 2000, Longitude, a television dramatisation of Dava Sobel's book Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time, recounted in part Gould's work in restoring the Harrison chronometers. In the drama, Gould was played by Jeremy Irons.[4]

Cryptozoology and paranormal interests

Gould took interest in investigating cryptozoological and paranormal claims.

Spurred on by the attention to the Loch Ness Monster in the popular press (news) and his previous work on the sea serpent, Gould spent some days at Loch Ness travelling around it by motorcycle. He interviewed many witnesses and collated evidence for the creature that resulted in the first major work on the phenomenon, entitled The Loch Ness Monster and Others. After this, Gould became the de facto spokesman on the subject, being a regular contributor to radio shows and newspaper articles.

Historian Mike Dash has described Gould as "Britain's answer to Charles Fort".[5] Paranormal writer Jerome Clark has described Gould as a "conservative and analytical" Fortean writer.[6] However, sceptical investigator Joe Nickell has described Gould as an "overly credulous paranormalist".[7]

Selected works

All works published as Rupert T. Gould. For a full bibliography of all Gould's works, see Betts 2006, Appendix 1.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1923). The Marine Chronometer, its history and development. London: J. D. Potter. ISBN 0-907462-05-7.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1928). Oddities: A Book of Unexplained Facts. London: Philip Allan & Co. Ltd.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1929). Enigmas: Another Book of Unexplained Facts. London: Philip Allan.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1930). The Case for the Sea Serpent. London: Philip Allan.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1934). The Loch Ness Monster and Others. London: Geoffrey Bles. Paperback, Lyle Stuart, 1976, ISBN 0-8065-0555-9

- Gould, Rupert T. (1935). Captain Cook. London: Duckworth.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1937). A Book of Marvels. London: Methuen.

- Gould, Rupert T. (1943). The Stargazer Talks. London: Geoffrey Bles.

- Gould, Rupert T.; Betts, Jonathan; Hecht, Susannah (2013). The Marine Chronometer, its history and development (2nd ed.). Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 978-1-85149-365-4.

See also

References

- Obituary: Commander Rupert Gould, R. N. The Geographical Journal. Vol. 112, No 4/6 (Oct. - Dec., 1948), pp. 258–259.

- "Gould, Rupert Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40920. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Betts, Jonathan, 2006

- "Longitude © (1999)". movie-dude.com. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Dash, Mike. (1999). "Rupert T. Gould: scholar, broadcaster, officer and not-quite-gentleman". Charles Fort Institute.

- Clark, Jerome. (1993). Encyclopedia of Strange and Unexplained Physical Phenomena. Gale Research Incorporated. p. 73

- Nickell, Joe. (1999). The Silver Lake Serpent: Inflated Monster or Inflated Tale? Skeptical Inquirer 23 (2): 18-21.

- Betts, Jonathan (2006). Time Restored - The Harrison Timekeepers and R.T.Gould, the man who knew (almost) everything. Oxford University Press and National Maritime Museum. ISBN 0-19-856802-9.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Archives Hub (2000–2010). "Rupert Gould collection". JISC: University of Manchester. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Lieutenant Commander Rupert T. Gould RN". Archived from the original on 21 April 2005. Retrieved 21 March 2006.