Russel Wright

Russel Wright (April 3, 1904 – December 21, 1976) was an American industrial designer. His best-selling ceramic dinnerware was credited with encouraging the general public to enjoy creative modern design at table with his many other ranges of furniture, accessories, and textiles. The Russel and Mary Wright Design Gallery at Manitoga in upstate New York records how the "Wrights shaped modern American lifestyle".[1]

Russel Wright | |

|---|---|

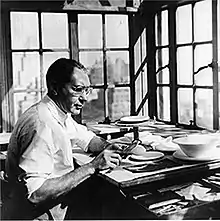

Russel Wright at work in his New York City studio. He also frequently worked at "Dragon Rock", part of his Manitoga home/studio in Garrison, New York, USA. | |

| Born | April 3, 1904 Lebanon, Ohio, US |

| Died | December 21, 1976 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Industrial design |

| Movement | American Modern |

| Spouse | Mary Small Einstein (1927–1952; her death) |

| Children | Annie |

Designer

Wright's approach to design came from the belief that the dining table was the center of the home. Working outward from there, he designed tableware to larger furniture, architecture to landscaping, all fostering an easy, informal lifestyle. It was through his popular and widely distributed housewares and furnishings that he impacted the way many Americans lived and organized their homes in the mid-20th century.[2]

In 1927 Wright married Mary Small Einstein, a designer, sculptor, and businesswoman, after a short yet carefree summer together in Woodstock, New York, where they were involved in the New York artist's Maverick Festival and artist colony.[3] Mary studied sculpture under Alexander Archipenko. Together Mary and Russel went on to form Wright Accessories, a home accessories design business, and began creating small objects for the home consisting of cast metal animals and informal serving accessories of spun aluminum and other materials. The couple also wrote the best-selling Guide to Easier Living in 1950, which described how to reduce housework and increase leisure time through efficient design and household management.[4]

Russel Wright Studios continues to work with corporate and public clients in the licensing and manufacturing of his designs and products.

Dinnerware

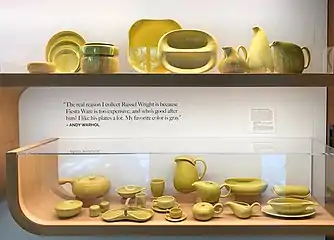

Wright is best known for his colorful American Modern design, the most widely sold American ceramic dinnerware in history, manufactured between 1939 and 1959 by Steubenville Pottery in Steubenville, Ohio.[5] Another iconic design was Wright's "American Modern" flatware designs for John Hull Cutlers Corporation in c. 1951.[6] He also designed top selling wooden furniture, spun aluminum dining accessories and textiles. His simple, practical style was influential in persuading ordinary Americans to embrace Modernism in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Wright's trademarked signature was the first to be identified with lifestyle-marketed products.[7]

._Residential_Pattern_Serving_Set%252C_ca.1953.jpg.webp)

Wright designed several popular lines of Melmac melamine resin plastic dinnerware for the home and did early research on plastic Melmac dinnerware for restaurant use. Wright's first Melmac line of plastic dinnerware for the home, called "Residential" was manufactured by Northern Plastic Company of Boston beginning in 1953. "Residential" received the Museum of Modern Art Good Design Award in 1953. "Residential" was one of the most popular Melmac lines with gross sales of over $4 million in 1957. The line remained popular for many years continuing in production by Home Decorators, Inc. of Newark, New York. Wright introduced his Melmac dinnerware line called "Flair" in 1959. One of the patterns of "Flair", called "Ming Lace" has the actual leaves of the Chinese jade orchid tree tinted and embedded inside the translucent plastic. As with his ceramic dinnerware, Wright began designing his Melmac only in solid colors, but by the end of the 1950s created several patterns ornamented with decoration, usually depicting plant forms.

Furniture

Wright designed a succession of popular furniture lines for many furniture companies beginning in the early 1930s through the 1950s. His most popular line of essentially Art Deco American Modern "blonde" wooden furniture was produced by the Conant-Ball company of Gardner, Massachusetts between 1935 and 1939, and bore the branded mark "American Modern Built by Conant-Ball Co. Designed by Russel Wright".[8]

Wright also worked with the Old Hickory Furniture Company in Martinsville, Indiana on unique rustic furniture with Wright's modern stylings. The collection was introduced in 1942 and some of the designs stayed popular through the 1950s.[9]

Career

Russel's early art training was under Frank Duveneck at the Art Academy of Cincinnati while still in high school. While following his family's tradition of studying for a legal career at Princeton University, he was a member of the Princeton Triangle Club and won several Tiffany & Co. prizes for outstanding World War I memorial sculptures. This, along with the urging of his academic adviser at Princeton, confirmed his conviction gained in the year before college while a student at the Art Students League of New York under Kenneth Hayes Miller and Boardman Robinson, that his future was in the field of art.

Wright left Princeton for the New York City theater world and quickly became a set designer for Norman Bel Geddes. This early association with the theater led to further work with George Cukor, Lee Simonson, Robert Edmond Jones, and Rouben Mamoulian. His theater career came to an end when George Cukor closed his Rochester, New York stock company at the end of 1927. Upon returning to New York City, he started his own design firm making theatrical props and small decorative cast metal objects.

Although firmly rooted in the Midwest, he spent the entirety of his professional artistic career in New York, employing such early instrumental modern design practitioners and artists as Petra Cabot, Henry P. Glass and Hector Leonardi [10] in his growing industrial design firm.

Personal life

Russel Wright was born in Lebanon, Ohio[4] into a historic old American family,[11] Wright's mother had direct lineage with two signers of the Declaration of Independence, and his father and grandfather were local judges. Both his parents were Quakers.[4]

Wright's only child, Annie, was only two years old when Mary died in 1952, necessitating Wright's raising their adopted daughter as a single parent. Annie Wright continues to manage her father's designs and products through Russel Wright Studios.[12]

Manitoga

After his wife's death, Russel Wright retired to his 75-acre (300,000 m2) estate, Manitoga in Garrison, New York, building an eco-sensitive Modernist home and studio called Dragon Rock surrounded by extensive woodland gardens.[12] Dragon Rock is constructed of wood, stone, and glass, and has been considered "one of the most idiosyncratic homes in the country". Wright designed the site, creating eleven woodland walking trails. Development of the site included in-filling a quarry and rerouting a stream.[13]

The house includes furniture that he designed or modified, as well as the Russel and Mary Wright Design Gallery where his pottery and functional objects for the home are displayed.[14]

It is on the National Register of Historic Places and a US Department of Interior designated National Historic Landmark. Manitoga is open to the public, operated by the non-profit Russel Wright Design Center, with tours and hiking trails. [15]

Collections

Wright's work is found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;[7] the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum of the Smithsonian Institution;[16] the Museum of Modern Art, New York;[17] the Brooklyn Museum;[18] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston;[19] Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center;[20] and other public collections.

Archive

The "Russel Wright Papers" from 1931–1965 are held in an archive at Syracuse University Library Special Collections Research Center, containing 60 feet (18 m) of architectural drawings, photographs, manuscripts, models and ephemera.[21]

References

- LaDuke, Sarah. "The Russel & Mary Wright Design Gallery Now Open At Manitoga". WAMC - Northeast Public Radio. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- Holzman, Malcolm. "Transforming the American Home". Manitoga. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Maverick Festival Personalities". SUNY New Paltz. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Pilgrim, Diane H. "A Singular Artist". Manitoga. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Russel Wright". Collectors Weekly. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- (July 6, 2020). John Hull Cutlers cutlery designs, exhibitions and historical information. artdesigncafe. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- "American Modern Dinnerware (1937) Russel Wright". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Conroy, Sarah Booth (5 November 1983). "Russel Wright". Washington Post. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Kylloe, Ralph (2009). Hickory Furniture. Gibbs Smith Publisher. p. 53. ISBN 9781423609971. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Hector-leonardi.com: Leonardi biography

- Russel Wright | People | Collection of Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

- Leavitt, David. "The Origin of Dragon Rock". Manitoga. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Hales, Linda (5 January 2002). "The Man With The Wright Stuff". Washington Post. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- "Russel and Mary Wright Design Gallery". Manitoga: Russel Wright Design Center. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Russel-wright-center.org: 'Manitoga' Archived 2010-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Russel Wright". Cooper Hewitt Museum. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Russel Wright American, 1904–1976". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "Russel Wright – American, 1904-1976". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- "(Search results)". MFA Boston. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 2023-03-11.

- "Russel & Mary Wright Design Gallery". Manitoga. Retrieved 2023-03-11.

- "Russel Wright Papers". Retrieved 30 October 2021.

Bibliography

- Guide to Easier Living by Mary and Russel Wright. (Reprint, Gibbs Smith, 2003) ISBN 1-58685-210-8.

- Russel Wright: Good Design Is For Everyone - In His Own Words Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center. (Universe, 2001) ISBN 0-9709459-1-4.

- Russel Wright: creating American lifestyle by Donald Albrecht, Robert Schonfeld, Lindsay Stamm Shapiro. Catalog of an exhibition at Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York (Harry N. Abrams, 2001) ISBN 0-8109-3278-4.

- Collector's Encyclopedia of Russel Wright by Ann Kerr (Collector Books, 2002, 3rd Edition) ISBN 1-57432-256-7, ISBN 978-1-57432-256-9.