Russian battleship Petropavlovsk (1894)

Petropavlovsk (Russian: Петропавловск) was the lead ship of her class of three pre-dreadnought battleships built for the Imperial Russian Navy during the last decade of the 19th century. The ship was sent to the Far East almost immediately after entering service in 1899, where she participated in the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion the next year and was the flagship of the First Pacific Squadron.

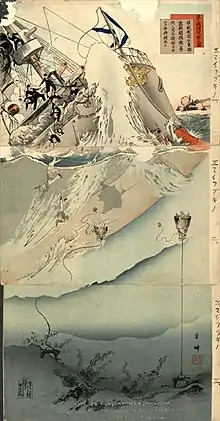

A Russian postcard of Petropavlovsk | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Petropavlovsk |

| Namesake | Battle of Petropavlovsk |

| Builder | Galernii Island Shipyard, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Laid down | 19 May 1892[Note 1] |

| Launched | 9 November 1894 |

| In service | 1899 |

| Fate | Sunk by mine off Port Arthur, 13 April 1904 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Petropavlovsk-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 11,354 long tons (11,536 t) |

| Length | 376 ft (114.6 m) |

| Beam | 70 ft (21.3 m) |

| Draft | 28 ft 3 in (8.61 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 shafts; 2 triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Range | 3,750 nmi (6,940 km; 4,320 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 725 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

At the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Petropavlovsk took part in the Battle of Port Arthur, where she was lightly damaged by Japanese shells and failed to score any hits in return. On 13 April 1904, the ship sank after striking one or more mines near Port Arthur, in northeast China. Casualties numbered 27 officers and 652 enlisted men, including Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov, the commander of the squadron, and the war artist Vasily Vereshchagin. The arrival of the competent and aggressive Makarov after the Battle of Port Arthur had boosted Russian morale, which plummeted after his death.

Design and description

The design of the Petropavlovsk-class ships was derived from the battleship Imperator Nikolai I, but was greatly enlarged to accommodate an armament of four 12-inch (305 mm) and eight 8-inch (203 mm) guns. While under construction, their armament was revised to consist of more powerful, higher-velocity, 12-inch guns; the 8-inch guns were replaced by a dozen 6-inch (152 mm) guns. The ships were 376 feet (114.6 m) long overall, with a beam of 70 feet (21.3 m) and a draft of 28 feet 3 inches (8.6 m). Designed to displace 10,960 long tons (11,140 t), Petropavlovsk was almost 400 long tons (410 t) overweight, displacing 11,354 long tons (11,536 t) when completed. The ship was powered by two vertical triple-expansion steam engines, built by the British firm Hawthorn Leslie, each driving one shaft, using steam generated by 14 cylindrical boilers. The engines were rated at 10,600 indicated horsepower (7,900 kW) and designed to reach a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph), but Petropavlovsk reached a speed of 16.38 knots (30.34 km/h; 18.85 mph) from 11,255 ihp (8,393 kW) during her sea trials. She carried enough coal to give her a range of 3,750 nautical miles (6,940 km; 4,320 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew numbered 725 men when serving as a flagship.[1]

The four 12-inch guns of the main battery were mounted in two twin-gun turrets, one forward and one aft of the superstructure. Designed to fire one round every 90 seconds, the actual rate of fire was half as fast. Their secondary armament consisted of twelve Canet six-inch quick-firing (QF) guns. Eight of these were mounted in four twin-gun wing turrets and the remaining guns were positioned in unprotected embrasures on the sides of the hull amidships. Smaller guns were carried for defense against torpedo boats, including a dozen QF 47-millimeter (1.9 in) Hotchkiss guns and twenty-eight Maxim QF 37-millimeter (1.5 in) guns. They were also armed with six torpedo tubes, four 15-inch (381 mm) tubes above water and two 18-inch (457 mm) submerged tubes, all mounted on the broadside. The ships carried 50 mines to be used to protect their anchorage.[2][3]

Russian manufacturers of the nickel-steel armor used by Petropavlovsk were unable to fulfill the existing demand, so the ship's armor was ordered from Bethlehem Steel in America. Her waterline armor belt was 12–16 inches (305–406 mm) thick. The main gun turrets had a maximum thickness of 10 inches (254 mm) and her deck armor ranged from 2–3 inches (51–76 mm) in thickness.[4]

Construction and career

Petropavlovsk was named for the successful Russian defense during the 1854 Siege of Petropavlovsk.[5] Delayed by shortages of skilled workmen, design changes, and late delivery of the main armament, the ship was constructed over a period of six years. She was laid down on 19 May 1892, together with her two sister ships, at the Galernii Island Shipyard and launched on 9 November 1894. Her trials lasted from 1898 to 1899, after which she was ordered to proceed to the Far East. Petropavlovsk departed Kronstadt on 17 October and arrived at Port Arthur on 10 May 1900, becoming the flagship of Vice Admiral Nikolai Skrydlov and the First Pacific Squadron. In mid-1900, the ship helped suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China.[6] In February 1902, Vice Admiral Oskar Stark assumed command of the squadron from Skrydlov and raised his flag on Petropavlovsk.[7] That same year, a radio was installed aboard the ship.[8]

Battle of Port Arthur

After the Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, both Russia and Japan had ambitions to control Manchuria and Korea, resulting in tensions between the two nations. Japan had begun negotiations to reduce the tensions in 1901, but the Russian government was slow and uncertain in its replies because it had not yet decided exactly how to resolve the problems. Japan interpreted this as deliberate prevarication designed to buy time to complete the Russian armament programs. The situation was worsened by Russia's failure to withdraw its troops from Manchuria in October 1903 as promised. The final straws were the news of Russian timber concessions in northern Korea and the Russian refusal to acknowledge Japanese interests in Manchuria while continuing to place conditions on Japanese activities in Korea. These actions caused the Japanese government to decide in December 1903 that war was inevitable.[9] As tensions with Japan increased, the Pacific Squadron began mooring in the outer harbor at night in order to react more quickly to any Japanese attempt to land troops in Korea.[10]

On the night of 8/9 February 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. Petropavlovsk was not hit and sortied the following morning when the Japanese Combined Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, attacked. Tōgō had expected the night attack by his ships to be much more successful than it was, and anticipated that the Russians would be badly disorganized and weakened, but they had recovered from their surprise and were ready for his attack. The Japanese ships were spotted by the protected cruiser Boyarin, which was patrolling offshore and alerted the Russian defenses. Tōgō chose to attack the Russian coastal defenses with his main armament and engage the ships with his secondary guns. Splitting his fire proved to be a poor decision as the Japanese 8- and 6-inch guns inflicted little damage on the Russian ships, which concentrated all their fire on the Japanese ships with some effect. Petropavlovsk was lightly damaged in the engagement by one 6-inch and two 12-inch shells, killing two and wounding five.[11] In return she fired twenty 12-inch and sixty-eight 6-inch shells at the Japanese battleships, but none hit.[12][13] Displeased by the poor performance of the First Pacific Squadron, the Naval Ministry replaced Stark with the dynamic and aggressive Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov,[14] regarded as the navy's most competent admiral,[15] on 7 March.[14] As a result of the damage incurred in the attack by the more heavily armored Tsesarevich and the subsequent lengthy repair time, Makarov was compelled to retain Petropavlovsk as his flagship, against his better judgement.[12][13]

Sinking

Having failed to blockade or bottle up the Russian squadron at Port Arthur by sinking blockships in the harbor's channel,[16] Tōgō formulated a new plan. Ships were to mine the entrance to the harbor and then lure the Russians into the minefield in the hopes of sinking a number of Russian warships. Covered by four detachments of torpedo boat destroyers, the minelayer Koru-Maru began to lay a minefield near the entrance to Port Arthur on the night of 31 March. The Japanese were observed by Makarov, who believed that they were Russian destroyers which he had ordered to patrol that area.[17]

Early on the morning of 13 April, the Russian destroyer Strashnii fell in with four Japanese destroyers in the darkness while on patrol. Once her captain realized his mistake, the Russian ship attempted to escape but failed after a Japanese shell struck one of her torpedoes and caused it to detonate. By this time the armored cruiser Bayan had sortied to provide support, but it was only able to rescue five survivors before a Japanese squadron of protected cruisers attacked. Escorted by three protected cruisers, Makarov led Petropavlovsk and her sister Poltava out to support Bayan, while ordering the rest of the First Pacific Squadron to follow as soon as they could. In the meantime, the Japanese had reported the Russian sortie to Tōgō, who arrived with all six Japanese battleships. Heavily outnumbered, Makarov ordered his ships to retreat and to join the rest of the squadron that was just exiting the harbor.[18] After the squadron had united and turned back towards the enemy, about two nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) from the shore, Petropavlovsk struck one or more mines at 09:42 and sank almost instantly,[19] taking with her 27 officers and 652 enlisted men, including Makarov and the war artist Vasily Vereshchagin.[20][21] Seven officers and 73 men were rescued.[8]

Makarov's arrival had boosted the morale of the squadron, and his death dispirited the sailors and their officers. His replacement, Rear Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, was a career staff officer unsuited to lead a navy at war. He did not consider himself a great leader, and his lack of charisma and passivity did nothing to restore the squadron's morale.[22][23][24] A monument was constructed in Saint Petersburg in 1913 to honor Makarov after Japanese divers identified his remains inside the wreck of Petropavlovsk and gave him a burial at sea.[21]

Notes

- All dates used in this article are New Style

References

- McLaughlin, pp. 84–85, 90.

- McLaughlin, pp. 84, 88–89.

- Friedman, p. 265.

- McLaughlin, pp. 84–85, 89–90.

- Silverstone, p. 381.

- McLaughlin, pp. 84, 86, 90.

- Kowner, p. 358.

- McLaughlin, p. 90.

- Westwood, pp. 15–21.

- McLaughlin, p. 160.

- Forczyk, pp. 41–43.

- Gribovskij, p. 49.

- Balakin, p. 38.

- Forczyk, p. 44.

- Westwood, p. 46.

- Grant, pp. 48–50.

- Balakin, pp. 33–36.

- Corbett, I, pp. 179–82.

- Vinogradov, pp. 72–73.

- Balakin, p. 39.

- Taras, p. 27.

- Forczyk, p. 46.

- McLaughlin, p. 162.

- Westwood, p. 50.

Sources

- Balakin, Sergei (2004). Морские сражения русско-японской войны 1904–1905 [Naval Battles of the Russo-Japanese War] (in Russian). Moscow: Morskaya Kollektsya (Maritime Collection). LCCN 2005429592.

- Corbett, Julian S. (1994). Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War. Annapolis, Maryland & Newport, Rhode Island: Naval Institute Press & Naval War College Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-129-5.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-330-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Grant, R. Captain (1907). Before Port Arthur in a Destroyer; The Personal Diary of a Japanese Naval Officer. London: John Murray. OCLC 31387560.

- Gribovskij, V. (1994). "The Catastrophe of March 31 of 1904 (The Wreck of the Battleship Petropavlovsk)". Gangut (in Russian). 4. ISSN 2218-7553.

- Nicolai Ivanovich Kravchenko. The Last Days and the Death of V. V. Vereshchagin: Memoirs of N.I. Kravchenko. – SPb. : Typography of. E. Manasevich, [B.G.] (1904).

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4927-3.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2003). Russian & Soviet Battleships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-481-4.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-88254-979-8.

- Taras, Alexander (2000). Корабли Российского императорского флота 1892–1917 гг [Ships of the Imperial Russian Navy 1892–1917]. Library of Military History (in Russian). Minsk: Kharvest. ISBN 978-985-433-888-0.

- Vinogradov, Sergei; Fedechkin, Aleksei (2011). Bronenosnyi kreyser "Bayan" i yego potomki. Od Port-Artura do Moonzunda [Armored Cruiser "Bayan" and her Offspring. From Port Artur to Moonsund.] (in Russian). Moscow: Yauza / EKSMO. ISBN 978-5-699-51559-2.

- Westwood, J. N. (1986). Russia Against Japan, 1904–1905: A New Look at the Russo-Japanese War. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-191-2.