Ruthenia

Ruthenia[lower-alpha 1] is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin, as one of several terms for Kievan Rus'.[1] It is also used to refer to the East Slavic and Eastern Orthodox regions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, and later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, corresponding to what is now Belarus and Ukraine.[2][3][4][5] Historically, the term was used to refer to all the territories of the East Slavs.[6][7]

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria (1772–1918), corresponding to parts of Western Ukraine, was referred to as Ruthenia and its people as Ruthenians.[4] As a result of a Ukrainian national identity gradually dominating over much of present-day Ukraine in the 19th and 20th centuries, the endonym Rusyn is now mostly used among a minority of peoples on the territory of the Carpathian Mountains, including Carpathian Ruthenia.[8]

Etymology

The word Ruthenia originated as a Latin designation of the region its people called Rus'. During the Middle Ages, writers in English and other Western European languages applied the term to lands inhabited by Eastern Slavs.[9][10] Russia itself was called Great Ruthenia or White Ruthenia until the end of the 17th century.[11] "Rusia or Ruthenia" appears in the 1520 Latin treatise Mores, leges et ritus omnium gentium, per Ioannem Boëmum, Aubanum, Teutonicum ex multis clarissimis rerum scriptoribus collecti by Johann Boemus. In the chapter De Rusia sive Ruthenia, et recentibus Rusianorum moribus ("About Rus', or Ruthenia, and modern customs of the Rus'"), Boemus tells of a country extending from the Baltic Sea to the Caspian Sea and from the Don River to the northern ocean. It is a source of beeswax, its forests harbor many animals with valuable fur, and the capital city Moscow (Moscovia), named after the Moskva River (Moscum amnem), is 14 miles in circumference.[12][13] Danish diplomat Jacob Ulfeldt, who traveled to Russia in 1578 to meet with Tsar Ivan IV, titled his posthumously (1608) published memoir Hodoeporicon Ruthenicum[14] ("Voyage to Ruthenia").[15]

Early Middle Ages

European manuscripts dating from the 11th century used the name Ruthenia to describe Rus', the wider area occupied by the early Rus' (commonly referred to as Kievan Rus'). This term was also used to refer to the Slavs of the island of Rügen[16] or to other Baltic Slavs, whom 12th-century chroniclers portrayed as fierce pirate pagans—even though Kievan Rus' had converted to Christianity by the 10th century:[17] Eupraxia, the daughter of Rutenorum rex Vsevolod I of Kiev, had married the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV in 1089.[18] After the devastating Mongolian occupation of the main part of Ruthenia which began in the 13th century, western Ruthenian principalities became incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, after which the state became called the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Ruthenia.[19][20] The Polish Kingdom also took the title King of Ruthenia[21] when it annexed Galicia. These titles were merged when the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was formed. A small part of Rus' (Transcarpathia, now mainly a part of Zakarpattia Oblast in present-day Ukraine), became subordinated to the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century.[22] The Kings of Hungary continued using the title "King of Galicia and Lodomeria" until 1918.[23]

Late Middle Ages

By the 15th century, the Moscow principality had established its sovereignty over a large portion of Ruthenian territory and began to fight with Lithuania over the remaining Ruthenian lands.[24][25] In 1547, the Moscow principality adopted the title of The Great Principat of Moscow and Tsardom of the Whole Rus and claimed sovereignty over "all the Rus'" — acts not recognized by its neighbour Poland.[26] The Muscovy population was Eastern Orthodox and preferred to use the Greek transliteration Rossiya (Ῥωσία)[27] rather than the Latin "Ruthenia".

In the 14th century, the southern territories of Rus', including the principalities of Galicia–Volhynia and Kiev, became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which in 1384 united with Catholic Poland in a union which became the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. Due to their usage of the Latin script rather than the Cyrillic script, they were usually denoted by the Latin name Ruthenia. Other spellings were also used in Latin, English, and other languages during this period. Contemporaneously, the Ruthenian Voivodeship was established in the territory of Galicia-Volhynia and existed until the 18th century.

These southern territories include:

- Galicia–Volhynia or the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia (Ukrainian: Галич-Волинь, romanized: Halych-Volyn or Галицько-Волинське королівство, Halytsko-Volynske korolivstvo; Polish: Ruś Halicko-Wołyńska or Księstwo halicko-wołyńskie)

- Galicia (Ukrainian: Галич, romanized: Halych or Галицько-Волинська Русь, Halytsko-Volynska Rus; Polish: Ruś Halicka)

- White Ruthenia, (eastern part of modern Belarus; Belarusian: Белая Русь, romanized: Belaia Rus; Polish: Ruś Biała)

- Black Ruthenia (a western part of modern Belarus; Belarusian: Чорная Русь, romanized: Chornaia Rus Polish: Ruś Czarna)

- Galicia, or Red Ruthenia, western Ukraine and southeast Poland; Ukrainian: Червона Русь, romanized: Chervona Rus; Polish: Ruś Czerwona)

- Carpathian Ruthenia (Ukrainian: Карпатська Русь, romanized: Karpatska Rus; Polish: Ruś Podkarpacka, lit. 'Subcarpathian Ruthenia')

The Russian Tsardom was officially called Velikoye Knyazhestvo Moskovskoye (Великое Княжество Московское), the Grand Duchy of Moscow, until 1547, although Ivan III (1440–1505, r. 1462–1505) had earlier borne the title "Great Tsar of All Russia".[28]

Early modern period

During the early modern period, the term Ruthenia started to be mostly associated with the Ruthenian lands of the Polish Crown and the Cossack Hetmanate. Bohdan Khmelnytsky declared himself the ruler of the Ruthenian state to the Polish representative Adam Kysil in February 1649.[29]

The Grand Principality of Ruthenia was the project name of the Cossack Hetmanate integrated into the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth.

Modern period

Ukraine

The use of the term Rus/Russia in the lands of Rus' survived longer as a name used by Ukrainians for Ukraine. When the Austrian monarchy made the vassal state of Galicia–Lodomeria into a province in 1772, Habsburg officials realized that the local East Slavic people were distinct from both Poles and Russians and still called themselves Rus. This was true until the empire fell in 1918.[30]

In the 1880s through the first decade of the 20th century, the popularity of the ethnonym Ukrainian spread, and the term Ukraine became a substitute for Malaya Rus' among the Ukrainian population of the empire. In the course of time, the term Rus became restricted to western parts of present-day Ukraine (Galicia/Halych, Carpathian Ruthenia), an area where Ukrainian nationalism competed with Galician Russophilia.[31] By the early 20th century, the term Ukraine had mostly replaced Malorussia in those lands, and by the mid-1920s in the Ukrainian diaspora in North America as well.

Rusyn (the Ruthenian) has been an official self-identification of the Rus' population in Poland (and also in Czechoslovakia). Until 1939, for many Ruthenians and Poles, the word Ukrainiec (Ukrainian) meant a person involved in or friendly to a nationalist movement.[32]

Modern Ruthenia

After 1918, the name Ruthenia became narrowed to the area south of the Carpathian Mountains in the Kingdom of Hungary, also called Carpathian Ruthenia (Ukrainian: карпатська Русь, romanized: karpatska Rus, including the cities of Mukachevo, Uzhhorod, and Prešov) and populated by Carpatho-Ruthenians, a group of East Slavic highlanders. While Galician Ruthenians considered themselves Ukrainians, the Carpatho-Ruthenians were the last East Slavic people who kept the historical name (Ruthen is a Latin form of the Slavic rusyn). Today, the term Rusyn is used to describe the ethnicity and language of Ruthenians, who are not compelled to adopt the Ukrainian national identity.

Carpathian Ruthenia (Hungarian: Kárpátalja, Ukrainian: Закарпаття, romanized: Zakarpattia) became part of the newly founded Hungarian Kingdom in 1000. In May 1919, it was incorporated with nominal autonomy into the provisional Czechoslovak state as Subcarpathian Rus'. Since then, Ruthenian people have been divided into three orientations: Russophiles, who saw Ruthenians as part of the Russian nation; Ukrainophiles, who like their Galician counterparts across the Carpathian Mountains considered Ruthenians part of the Ukrainian nation; and Ruthenophiles, who claimed that Carpatho-Ruthenians were a separate nation and who wanted to develop a native Rusyn language and culture.[33]

In 1938, under the Nazi regime in Germany, there were calls in the German press for the independence of a greater Ukraine, which would include Ruthenia, parts of Hungary, the Polish Southeast including Lviv, the Crimea, and Ukraine, including Kyiv and Kharkiv. (These calls were described in the French and Spanish press as "troublemaking".)[34]

On 15 March 1939, the Ukrainophile president of Carpatho-Ruthenia, Avhustyn Voloshyn, declared its independence as Carpatho-Ukraine. On the same day, regular troops of the Royal Hungarian Army occupied and annexed the region. In 1944 the Soviet Army occupied the territory, and in 1945 it was annexed to the Ukrainian SSR. Rusyns were not an officially recognized ethnic group in the USSR, as the Soviet government considered them to be Ukrainian.

A Rusyn minority remained, after World War II, in eastern Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia). According to critics, the Ruthenians rapidly became Slovakized.[35] In 1995 the Ruthenian written language became standardized.[36]

Following Ukrainian independence and dissolution of the Soviet Union (1990–91), the official position of the government and some Ukrainian politicians has been that the Rusyns are an integral part of the Ukrainian nation. Some of the population of Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine have identified as Rusyn (or Boyko, Hutsul, Lemko etc) first and foremost; a subset of this second group has, nevertheless, considered Rusyns to be part of a broader Ukrainian national identity.

Ruthenium

The Baltic German naturalist and chemist Karl Ernst Claus, member of the Russian Academy of Science, was born in 1796 in Dorpat (Tartu), then in the Governorate of Livonia of the Russian Empire, now in Estonia. In 1844, he isolated the element ruthenium from platinum ore found in the Ural Mountains and named it after Ruthenia, which was meant to be the Latin name for Russia.[37]

Gallery

_pt.svg.png.webp) Principalities of Kievan Rus' (1054-1132)

Principalities of Kievan Rus' (1054-1132) Kingdom of Ruthenia (13th-14th century)

Kingdom of Ruthenia (13th-14th century) Ruthenian Voivoideship (14th-18th century)

Ruthenian Voivoideship (14th-18th century) Grand Principality of Ruthenia shown in dark yellow (1658 project)

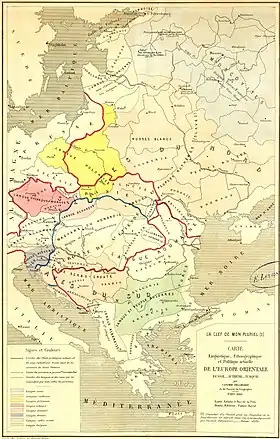

Grand Principality of Ruthenia shown in dark yellow (1658 project) "ruthenian languages and people" mentioned in the linguistic and political map of Eastern Europe by Casimir Delamarre (1868)

"ruthenian languages and people" mentioned in the linguistic and political map of Eastern Europe by Casimir Delamarre (1868) 1911 map of Austro-Hungary showing ethnic Ruthenians in light-green in eastern Galicia

1911 map of Austro-Hungary showing ethnic Ruthenians in light-green in eastern Galicia

See also

Notes

References

- Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: the role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age communication across the Baltic Sea. Leiden: Brill. p. 166. ISBN 9789004363816.

- Gasparov, Boris; Raevsky-Hughes, Olga (July 2021). California Slavic Studies, Volume XVI: Slavic Culture in the Middle Ages. Univ of California Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-520-30918-0.

- Nazarenko, Aleksandr Vasilevich (2001). "1. Имя "Русь" в древнейшей западноевропейской языковой традиции (XI-XII века)" [The name Rus' in the old tradition of Western European language (XI-XII centuries)]. Древняя Русь на международных путях: междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX-XII веков [Old Rus' on international routes: Interdisciplinary Essays on cultural, trade, and political ties in the 9th-12th centuries] (DJVU) (in Russian). Languages of the Rus' culture. pp. 40, 42–45, 49–50. ISBN 978-5-7859-0085-1. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

Besides the Greco-Byzantine term Rosia to describe Rus', Latin documents used several related terms – Ruscia, Russia, Ruzzia – for Kievan Rus' as a whole. Subsequently, the terms Ruteni and Rutheni were used to describe Ukrainian and Belarusan Eastern Christians (especially members of the Uniate, later Greek Catholic, Church) residing in the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The German, French, and English versions of those terms – Ruthenen, Ruthène, Ruthenian – generally were applied only to the inhabitants of Austrian Galicia and Bukovina of Hungarian Transcarpathia.

- Handbook of language and ethnic identity. Vol. 2: The success-failure continuum in language and ethnic identity efforts, volume 2. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. 2011. p. 384. ISBN 978-0195392456.

- Dyczok, Marta (2000). Ukraine: movement without change, change without movement. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publ. p. 23. ISBN 9789058230263.

- The later middle ages (Fifth ed.). North York, Ontario, Canada Tonawanda, New York Plymouth: University of Toronto Press. 2016. p. 699. ISBN 978-1442634374.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2015). With their backs to the mountains: a history of Carpathian Rus' and Carpatho-Rusyns. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-6155053399.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2011.

Rvcia hatte Rutenia and is a prouynce of Messia (J. Trevisa, 1398).

- Armstrong, John Alexander (1982). Nations Before Nationalism. University of North Carolina Press (published 2017). p. 228. ISBN 9781469620725. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

From the linguistic standpoint, the results of this catastrophe [the Mongol invasion] somewhat resemble the collapse of the Roman empire for the latin-speaking peoples. Like the great 'Romania' of the Western Middle Ages, there was a great 'Ruthenia' in which common linguistic origin and some measure of mutual comprehensibility was assumed.

- Флоря, Борис (2017). "О некоторых особенностях развития этнического самосознания восточных славян в эпоху средневековья – раннего Нового времени". In Флоря, Борис; Миллер, Алексей; Репринцев, В. (eds.). Russia – Ukraine: a history of mutual relations (collection) Россия – Украина. История взаимоотношений (сборник) [Rossiya – Ukraina. Istoriya vzaimootnosheniy (sbornik)] (in Russian). Moscow: Shkola YAzyki russkoi kultury. pp. 9–28. ISBN 9785457502383. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Мыльников, Александр (1999). Картина славянского мира: взгляд из Восточной Европы: Представления об этнической номинации и этничности XVI-начала XVIII века. Saint Petersburg: Петербургское востоковедение. pp. 129–130. ISBN 5-85803-117-X.

- Сынкова, Ірына (2007). "Ёган Баэмус і яго кніга "Норавы, законы і звычаі ўсіх народаў"". Беларускі Гістарычны Агляд. 14 (1–2).

- Ulfeldt, Jacob (1608). Hodoeporicon Ruthenicum, in quo de Moscovitarum Regione, Moribus, Religione, gubernatione, & Aula Imperatoria quo potuit compendio & eleganter exequitur [...] (in Latin) (1 ed.). Frankfurt. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

-

Kasinec, Edward; Davis, Robert H. (2006). "The Imagery of Early Anglo-Russian Relations". In Dmitrieva, Ol'ga; Abramova, Natalya (eds.). Britannia & Muscovy: English Silver at the Court of the Tsars. Yale University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780300116786. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

[...] [Jacob Ulfeldt's] Hodoeporicon Ruthenicum ['Ruthenian Journey'] (Frankfurt, 1608 [...]) [...].

- "The Life of Otto, Apostle of Pomerania, 1060-1139". Society for promoting Christian knowledge. 28 July 1920 – via Google Books.

- Paul, Andrew (2015). "The Roxolani from Rügen: Nikolaus Marshalk's chronicle as an example of medieval tradition to associate the Rügen's Slavs with the Slavic Rus". The Historical Format. 1: 5–30.

- Annales Augustani. 1839. p. 133.

- Parker, William Henry (28 July 1969). "An Historical Geography of Russia". Aldine Publishing Company – via Google Books.

- Kunitz, Joshua (28 July 1947). "Russia, the Giant that Came Last". Dodd, Mead – via Google Books.

- Document Nr 1340 (CODEX DIPLOMATICUS MAIORIS POLONIA). POZNANIAE. SUMPTIBUS BIBLIOTHECAE KORNICENSIS. TYPIS J. I. KRASZEWSKI (Dr. W. ŁEBIŃSKI). 1879.

- Magocsi 1996, p. 385.

- Francis Dvornik (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. Rutgers University Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Grand Principality of Moscow Britannica

- Ivan III Britannica

- Dariusz Kupisz, Psków 1581–1582, Warszawa 2006, s. 55–201.

- T. Kamusella (16 December 2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-230-58347-4.

- Trepanier, Lee (2010). Political Symbols in Russian History: Church, State, and the Quest for Order and Justice. Lexington Books. pp. 38–39, 60. ISBN 9780739117897.

- "Khmelnychyna". Izbornyk - History of Ukraine IX-XVIII centuries. Sources and Interpretations (in Ukrainian). Encyclopedia of Ukrainian Studies. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Vernadsky, George. A History of Russia (1943–69). Pp. xix, 413. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-00247-5.

- Magocsi 1996, p. 408-409,444:"Throughout 1848, the Austrian government gave its support to the Ukrainians, both to their efforts to obtain recognition as a nationality and to their attempts to achieve political and cultural rights. In return, the Ukrainian leadership turned a blind eye to the political reaction and repressive measures that at the same time were being carried out by Habsburg authorities against certain other peoples in the empire" (pp. 408–409) ... "Most important from the standpoint of the debate as to the proper national orientation was the Austrian government's decision in 1893 to recognize the vernacular Ukrainian (Rusyn) language as the standard for instructional purposes. As a result of this decision, the Old Ruthenian and Russophile orientations were effectively eliminated from the all-important educational system" (pp. 444)

- Robert Potocki, Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930–1939, Lublin 2003, wyd. Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, ISBN 83-917615-4-1, s. 45.

- Gabor, Madame (Autumn 1938). "Ruthenia". The Ashridge Journal. 35: 27–39.

- Fabra (18 December 1938). "ALEMANIA ESTA CREANDO UN NUEVOFOCO DE PERTURBACIONES EN UCRAINA". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). p. 7. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

«Le Figaro» [...] la creación de una Ucraina independiente [...] un mapa de los territorios de raza ucrainiana en que se incluye a la Rutenia, una parte de Hungría, el sureste de Polonia con la ciudad de Lwow, y toda la Ucraina soviética, con Crimea y las ciudades de Kiev y Jarkov

- "The Rusyn Homeland Fund". carpatho-rusyn.org. 1998. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Paul Robert Magocsi: A new Slavic language is born, in: Revue des études slaves, Tome 67, fascicule 1, 1995, pp. 238–240.

- Pitchkov, V. N. (1996). "The Discovery of Ruthenium". Platinum Metals Review. 40 (4): 181–188.

Sources

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-06-097468-0

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1995). The Rusyn Question – Political Thought.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 385. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Why is the "Russia" White? - a book review of Ales Biely's Chronicle of Ruthenia Alba

- "Ruthenia – Spearhead Toward the West", by Senator Charles J. Hokky, Former Member of the Czechoslovakian Parliament (Book representing a Hungarian nationalist position)