Russian puppet theater

Russian puppet theater appears to have originated either in migrations from the Byzantine Empire in the sixth century or possibly by Mongols travelling from China. Itinerant Slavic minstrels were presenting puppet shows in western Russia by the thirteenth century, arriving in Moscow in the mid-sixteenth century. Although Russian traditions were increasingly influenced by puppeteers from western Europe in the eighteenth century, Petrushka continued to be one of the principal figures. In addition to glove puppets and marionettes, rod puppets and flat puppets were introduced for a time but disappeared in the late nineteenth century.

Today's puppet theaters owe much of their popularity to Nina Simonovich-Efimova and her husband who received support from the Russian authorities shortly after the October Revolution to set up a puppet theater in Moscow. They introduced a number of innovative designs and presented a range of performances for both children and adults. Sergey Obraztsov, who performed classical folk tales with glove puppets and marionettes, established his own theater in 1938. Puppet performances became increasingly widespread during the Soviet era and have remained popular ever since.

History

The origin of Russian puppetry is far from clear. It is often attributed to Italy, because of similarities between Petrushka and Pulcinella. Other theorists believe that their puppet theaters might have migrated from Byzantium into the East Slavic regions known as Kievan Rus' or that the Mongols could have brought the approach from China. Puppet theater had been popular in the west by the twelfth century and evidence indicates that it had begun to flourish as early as the sixth century in the Byzantine Empire.[1] Because of the nature of itinerant performers, many cultural traditions may well have been influenced by foreign interaction.[2] Ancient Slavic customs to celebrate solstice cycles show that there was a tradition of using masks and manikins in ceremonies to mark the end of one season and the beginning of another. In one such ceremony for Kupala Night, male dolls, called Kupalo, and female dolls, called Marena, are made of straw. The female dolls are repeatedly kidnapped forcing the women to renew their supply, until in the back and forth tug-of-war, the dolls are torn asunder and scattered.[3]

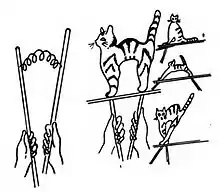

Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, the word used for theater in Russia was pozorishche, which was a distinct term from igrishche, a dramatic performance including live actors.[4] Kukla, the modern Russian term for puppet theater, was first used in 1699.[5] Itinerant minstrels known as skomorokhs were the original puppeteers in Russia and by the thirteenth century had relocated from Kievan Rus' to Novgorod. By the mid-sixteenth century, they shifted their activity to Moscow when Ivan IV ordered them to be taken there with their performing bears.[6] By the 1630s, puppets had become an integral part of the performances of the minstrels, including an innovative means of creating a stage with blankets tied at the waist and lifted over their heads with poles so that their hands were free to move their puppets.[7] In 1648, the skomorokhi were barred from further performances by a law that sought to wipe out superstition in the interests of Russian morality. From then on, puppets and traditions were increasingly imported from Germany and Denmark.[8] By the mid-eighteenth century, regular performances by French, German, and Italian puppetry companies were also common in Russia.[9]

Surviving playbills from the period show that by the 1730s, Petrushka had largely been replaced by Western heroes, though the twenty-three plays in which he was still featured show that he had certainly not been forgotten and had been largely unaffected by foreign influences.[9] By the eighteenth century, rod puppets were regularly seen performing in booths. The tradition arose in Russia and in surrounding countries including Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine when Nativity performances were banned from being held in churches. As the portable mangers were set up in more secular settings, the performances themselves also became less religious.[10]

Ivan Finogenovich Zaitsev was one of the nineteenth-century Russian puppeteers who worked with flat puppets cut from metal. These appeared on the stage through slots cut into the table and performed scenes of the Turko-Russian wars or comedies. One of his contemporaries, Jocovlevich Siezova, made similar puppets of wood,[11] but performances with such puppets died out in the late nineteenth century.[12] A 1908 parody of The Blue Bird which had been produced at the Moscow Art Theater was performed with puppets by Stanislavsky at the cabaret "The Bat"; Andrei Belyi and Nikolai Evreinov both failed in their attempts to stage puppet theaters; and two women, Olga Glébova-Soudeïkina and Liubov Shaporina, created dolls but were unable to achieve success with their marionette theater in the pre-revolutionary period.[13]

In 1916, when Nina Simonovich-Efimova performed for the Moscow Fellowship of Artists, there were few practicing the art.[14][15] That same year, Yulia Slonimskaya Sazonova created a marionette performance called The Forces of Love and Magic with opulent costuming, orchestration and staging, which garnered note.[16] Shaporina began sketching scenes and costumes for a puppet theater which she successfully launched in 1918 in Petrograd.[13][17]

Both Slonimskaia and Efimova worked not only to elevate the art of puppetry but wrote theatrical theories about puppets, their application, design and development.[15] By 1918, Efimova and her husband, Ivan Efimov, a sculptor, had been asked to set up a children’s theater in line with the government's socialist restructuring policy, becoming the first professional puppetmasters in Russia, earning themselves the title of the Adam and Eve of Russian puppetry.[18][19] Taking their hand puppet show on the road, the Efimovs sole means of support for six years was earned from their theater.[14] Through the course of her career, Efimova, who was the driving force behind the puppets, patented innovative designs for shadow plays using silhouettes, rod puppets as well as life-sized manikins,[20][21][22][23] in her attempts "to establish puppetry’s validity as a unique discipline".[24] Slonimskaia's work focused mainly on marionettes, which she later took to France, Portugal and the United States.[25]

By 1924, politically-motivated theaters had spring up in several locations, such as the Petrushka Theater, founded by Yevgeny Demmeni in Saint Petersburg. That theater merged with the Petrograd Marionette Theatre and was later renamed the Leningrad Puppet Theatre. In 1929, the Children’s Theatre Book opened and in 1931, the Bolshoi Puppet Theatre opened in Leningrad.[26] By the 1930s, state regulations required that all performances, i.e. circuses, variety shows, music performances and puppet theaters be controlled by GOMETs, the State Department created specifically for their regulation. One of the measures GOMETs put in place was that performances must be held in established theater venues and could no longer be itinerant street performances.[27] Sergey Obraztsov gave his first solo performance as a puppeteer in 1923, but worked mainly as a stage actor until 1931, when he was approached by the managers of the Central Children’s Art Studio to form a puppet theater. Becoming the art director of the Central State Puppet Theatre, Obraztsov staged parody-plays with themes geared toward both adults and children.[28][29] He performed with both glove puppets and marionettes, traveling in and around Moscow until 1938, when he established his own theater. After his theater was bombed during the war, he relocated to Novosibirsk until the war ended.[30] Obraztsov characters evoked a realistic expression and performed both classic folk tales and sophisticated literary works.[31]

During the Soviet era, theaters spread throughout the USSR to provincial towns like Arkhangelsk, Ivanovo, Nizhny Novgorod, Rostov, Rybinsk, Samara and Yaroslavl, as well as to other Soviet states. The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic developed a strong marionette tradition and in the Khakassian Republic, a puppet theater in Abakan gained note. There was an effort made to veer toward making puppets more humanistic and away from their folk art roots, which led away from use of marionettes and focus almost exclusively on glove or rod puppets.[31] In 1959, the Leningrad Institute for Music, Film, and Theater created a puppet department, formalizing state training for puppetmasters. During the policy reforms in the Gorbachev era, experimentation began with puppeteers appearing on-stage with their manikins and even with actors portraying puppet characters.[32] Revaz Gabriadze was one of the most widely known puppeteers from the end of the Soviet era.[33]

Present

In 2000 the Museum of Architecture in Moscow held an exhibition of puppets made by prominent performers to show variations in design and artistry associated with manikins. Puppet theater without the constraint of realism, has returned to its earlier roots. Marionettes have seen a re-emergence and a range of performance approaches, once again including shadow plays, and traditional puppet movement, are employed. Theater has moved away from both a venue solely for children and often features texts written, rather than adapted from other works, specifically for puppet performances.[32]

Some of the most noted theaters include: The puppet Theater of Ekaterinburg is renowned for employing some of the best known puppet designers in Russia. The Khakassian Puppet Theater Fairy Tale in Abakan is noted for its wooden manikins which perform typically biblical themes. The Arkhangelsk Puppet Theater tends to focus on cultural tradition, while the Theater Potudan in Saint Petersburg and the Theater Ten' are known as innovative venues.[34] When Theater Potudan opened, in 2002 its repertoire centered around the Andrei Platonov novella, "The River Potudan". It was expanded later that year to include an adaptation of Nikolai Gogol's story Nevsky Prospekt. The performances are for an adult audience and explore universal life themes.[35] Theater Ten' recreates intricate shadow plays parodying performances at the Bolshoi Theater. It also hosts events where performers introduce children to theatrical performance, explaining the nuances of various genres.[36]

References

Citations

- Zguta 1974, p. 709.

- Zguta 1974, p. 711.

- Zguta 1974, pp. 712–713.

- Zguta 1974, pp. 716–717.

- Zguta 1974, p. 715.

- Zguta 1974, pp. 717–718.

- Zguta 1974, p. 718.

- Zguta 1974, p. 719.

- Zguta 1974, p. 720.

- Batchelder 1947, pp. 122–123.

- Batchelder 1947, p. 140.

- Batchelder 1947, p. 142.

- Posner 2012, p. 120.

- Batchelder 1947, p. 173.

- Posner 2014, p. 130.

- Slonimsky 2012, p. 8.

- Фрумкина 2011.

- Posner 2012, pp. 126–127.

- Карпова 2016.

- Reeder 1989, p. 112.

- Batchelder 1947, p. 174.

- Posner 2014, p. 140.

- Lipetsk Regional Universal Scientific Library 2013.

- Posner 2012, p. 127.

- Slonimsky 2012, p. 8-9.

- Rubin, Nagy & Rouyer 2001, p. 730.

- Beumers 2005, p. 161.

- InfoCentre 2012.

- Tsarevskaya 2005.

- Balfour 2001, p. 178.

- Beumers 2005, p. 162.

- Beumers 2005, p. 163.

- Beumers 2005, p. 167.

- Beumers 2005, pp. 163–164.

- Beumers 2005, p. 164.

- Beumers 2005, pp. 166–167.

Bibliography

- Balfour, Michael (2001). Theatre and War, 1933-1945: Performance in Extremis. New York, New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-497-5.

- Batchelder, Marjorie Hope (1947). Rod-puppets and the Human Theatre. Contributions in fine arts,no. 3. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University Press. OCLC 537308814.

- Beumers, Birgit (2005). Pop Culture Russia!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-459-2.

- Фрумкина (Frumkin), Ревекка (Rebekah) (29 July 2011). "Дневник цельного человека" [Diary of the whole man]. Polit.ru (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Карпова (Karpova), Татьяна Игоревна (Tatyana Igorevna) (2016). "Симонович-Ефимова Нина Яковлевна: Биографическая Статья" [Simonovich-Efimova, Nina Yakovlevna: Biographical article]. Муравейник 53 (in Russian). Veliky Novgorod, Russia: Novgorod Electronic Library. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- Posner, Dassia N. (2014). "Life-Death and Disobedient Obedience: Russian Modernist Redefinitions of the Puppet". In Posner, Dassia N.; Orenstein, Claudia; Bell, John (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Puppetry and Material Performance. London, England: Routledge. pp. 131–143. ISBN 978-1-317-91172-2.

- Posner, Dassia N. (2012). "Sculpture in Motion: Nina Simonovich-Efimova and the Petrushka Theatre". In Fryer, Paul (ed.). Women in the Arts in the Belle Epoque: Essays on Influential Artists, Writers and Performers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 118–135. ISBN 978-0-7864-6075-5.

- Reeder, Roberta (Winter 1989). "Puppets: Moving Sculpture". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. University Park, Florida: Florida International University Board of Trustees on behalf of The Wolfsonian-FIU. 11 (2): 106–125. ISSN 0888-7314. JSTOR 1503985.

- Rubin, Don; Nagy, Peter; Rouyer, Philippe (January 2001). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Europe. Vol. 1. London, England: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-25157-0.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas (2012). Dear Dorothy: Letters from Nicolas Slonimsky to Dorothy Adlow. Rochester, New York: University Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-395-9.

- Tsarevskaya, Lyubov (2005). "Sergei Obraztsov's Puppet Theater". The Voice of Russia. Moscow, Russia: Rossiya Segodnya. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- Zguta, Russell (December 1974). "Origins of the Russian Puppet Theater: An Alternative Hypothesis". Slavic Review. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies by University of Pittsburgh. 33 (4): 708–720. doi:10.2307/2494509. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2494509.

- "Sergey Obraztsov". Russia InfoCentre. Moscow, Russia: Guarant Center, Moscow State University. 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Симонович-Ефимова, Нина Яковлевна (1877-1948)" [Simonovich-Efimova, Nina Yakovlevna (1877-1948)]. Лоунб.ru (in Russian). Lipetsk, Russia: Липецкая областная универсальная научная библиотека (Lipetsk Regional Universal Scientific Library). 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.