Onibi

Onibi (鬼火, "Demon Fire") is a type of atmospheric ghost light in legends of Japan. According to folklore, they are the spirits born from the corpses of humans and animals. They are also said to be resentful people that have become fire and appeared. Also, sometimes the words "will-o'-wisp" or "jack-o'-lantern" are translated into Japanese as "onibi".[1]

Outline

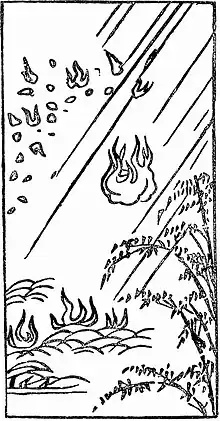

According to the Wakan Sansai Zue written in the Edo period, it was a blue light like a pine torchlight, and several onibi would gather together, and humans who come close would have their spirit sucked out.[2] Also, from the illustration in the same Zue, it has been guessed to have a size from about two or three centimeters in diameter to about 20 or 30 centimeters, and to float in the air about one or two meters from the ground.[1] According to Yasumori Negishi, in the essay "Mimibukuro" from the Edo period, in chapter 10 "Onibi no Koto", there was an anecdote about an onibi that appeared above Hakone mountain that split into two and flew around, gathered together again, and furthermore split several times.[3]

Nowadays, people have advanced several theories about their appearance and features.

- Appearance

- They are generally blue as stated previously,[1] but there are some that are bluish white, red, and yellow.[4][5] For their size, there are some as small as a candle flame, to ones about as large as a human, to some that even span several meters.[5]

- Number

- Sometimes only one or two of them appear, and also times when 20 to 30 of them would appear at once, and even times when countless onibi would burn and disappear all night long.[6]

- Times of frequent appearance

- They usually appear from spring to summer. They often appear on days of rain.[5]

- Places of frequent appearance

- They commonly appear in watery areas like wetlands, and also in forests, prairies, and graveyards, and they often appear in places surrounded by natural features, but rarely they appear in towns as well.[5]

- Heat

- There are some that, when touched, do not feel hot like a fire, but also some that would burn things with heat like a real fire.[5]

Types

As onibi are thought of as a type of atmospheric ghost light, there are ones like the below. Other than these, there is also the shiranui, the koemonbi, the janjanbi, and the tenka among others.[5] There is a theory that the kitsunebi is also a kind of onibi, but there is also the opinion that strictly speaking, they are different from onibi.[1]

- Asobibi (遊火, "play fire")

- It is an onibi that appears below the castle and above the sea in Kōchi, Kōchi Prefecture, and Mitani Mountain. One would think that it appeared very close, just for it to fly far away, and when one thinks that it has split apart several times, it would once again all come together. It is said to be of no particular harm to humans.[7]

- Igebo

- It is what onibi are called in the Watarai District, Mie Prefecture.[8]

- Inka (陰火, "shadow fire")

- It is an onibi that would appear together when a ghost or yōkai appears.[5]

- Kazedama (風玉, "wind ball")

- It is an onibi of the Ibigawa, Ibi district, Gifu Prefecture. In storms, it would appear as a spherical ball of fire. It would be about as big as a personal tray, and it gives off bright light. In the typhoon of Meiji 30 (1897), this kazedama appeared from the mountain and floated in the air several times.[9]

- Sarakazoe (皿数え, "count plate")

- It is an onibi that appeared in the Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki by Sekien Toriyama. In the Banchō Sarayashiki known from ghost stories, Okiku's spirit became appeared as an inka ("shadow fire") from the well, and was depicted as counting plates.[10]

- Sōgenbi (叢原火 or 宗源火, "religion source fire")

- It was an onibi in Kyoto in Sekien Toriyama's Gazu Hyakki Yagyō. It was stated to be a monk who once stole from the Jizōdō in Mibu-dera who received Buddhist punishment and became an onibi, and the anguishing face of the priest would float inside the fire.[11] The name also appeared in the "Shinotogibōko", a collection of ghost stories from the Edo period.[12]

- Hidama (火魂, "fire spirit")

- An onibi from the Okinawa Prefecture. It ordinarily lives in the kitchen behind the charcoal extinguisher, but it is said to become a bird-like shape and fly around, and make things catch on fire.[13]

- Wataribisyaku (渡柄杓, "transversing ladle")

- An onibi from Chii village, Kitakuwada District, Kyoto Prefecture (later, Miyama, now Nantan). It appears in mountain villages, and is a bluish white ball of fire that lightly floats in the air. It is said to have an appearance like a hishaku (ladle), but it is not that it actually looks like the ladle tool, but rather that it appeared to be pulling a long and thin tail, which was compared to a ladle as a metaphor.[14]

- Kitsunebi (狐火, "fox fire")

- It is a mysterious fire that has created various legends, there is the theory that a bone the fox is holding in its mouth is glowing. Kimimori Sarashina from Michi explained it as a refraction of light that occurs near river beds.[15] Sometimes kitsunebi are considered a type of onibi.[16]

Considerations

First, considering how the details about onibi from eyewitness testimony do not match each other, onibi can be thought of as a collective term for several kinds of mysterious light phenomenon. Since they frequently appear during days of rain, even though the "bi" (fire) is in its name, they have been surmised to be different from simply the flames of combustion, and is a different type of luminescent body.[5] It is especially of note that in the past, these phenomena were not strange.

In China in the BC era, it was said that "from the blood of human and animals, phosphorus and oni fire (onibi) comes". The character 燐 at that time in China could also mean the luminescence of fireflies, triboelectricity, and was not a word that indicated the chemical element "phosphorus".[1]

Meanwhile, in Japan, according to the explanation in the "Wakan Sansai Zue", for humans, horses, and cattle die in battle and stain the ground with blood, the onibi are what their spirits turn into after several years and months.[2]

One century after the "Wakan Sansai Zue" in the 19th century and afterwards in Japan, as the first to speak of them, they were mentioned in Shūkichi Arai's literary work "Fushigi Benmō", stating, "the corpses of those who are buried have their phosphorus turned into onibi". This interpretation was supported until the 1920s, and dictionaries would state this in the Shōwa period and beyond.[1]

Sankyō Kanda, a biologist of luminescent animals, found phosphorus in 1696, and as he knew that human bodies also had this phosphorus, in Japan, the character 燐 was applied to it, and thus it can be guessed that it was mixed in with the hint from China about the relation between onibi and phosphorus.[1] In other words, it could be surmised that when corpses decay, the phosphorus in phosphoric acid would give off light. In this way, many of the onibi would be explained, but there also remain many testimonies that do not match with the theory that of illumination from phosphorus.

After that, there is a theory that it is not phosphorus itself, but rather the spontaneous combustion of phosphine, or the theory that it is burning methane produced from the decay of the corpse, and also a theory that hydrogen sulfide is produced from the decay and becomes the source of the onibi, and also ones that would be defined in modern science as a type of plasma.[1] Since they often appear in days of rain, there are scientists that would explain that as Saint Elmo's fire (plasma phenomenon). The physicist Yoshihiko Ōtsuki also advanced the theory that these mysterious fires are caused by plasma.[17] It has also been pointed out that for the lights that would appear far in the middle of darkness, that if they are able to move by suggestion, then there is a possibility that they could simply be related to optical illusion phenomena.

Each of these theories has its own merits and demerits, and since the onibi legends themselves are of various kinds, it would be impossible to conclusively explain all of the onibi with a single theory.[1]

Furthermore, they are frequently confused with hitodama and kitsunebi, and as there are many different theories to explain them, and since the true nature of these onibi is unknown, there is no real clear distinction between them.[5]

Other

There are also legends that onibi would float about when ghosts appear in Europe, as in Germany on November 2 on All Souls' Night, a great number of onibi can be seen behind the temple in the graveyard. This was seen as proof that a long line of ghosts had come to the temple, and the ghosts of children wore a white undergarment, participating in the line by "Frau Holle (Mrs. Holle)".[18] Since they had appeared in a graveyard, an explanation was given that it was due to the gasses from decomposition as stated previously.

See also

Notes

- 不知火・人魂・狐火. pp. 37–67頁.

- 和漢三才図会. pp. 143–144頁.

- 耳嚢. pp. 402頁.

- 鈴木桃野 (1961). "反古のうらがき". In 柴田宵曲編 (ed.). 随筆辞典 第4巻 奇談異聞編. 東京堂. pp. 66–67頁.

- 幻想世界の住人たち. Vol. IV. pp. 231–234頁.

- 草野巧 (1997). 幻想動物事典. Truth in fantasy. 新紀元社. pp. 69頁. ISBN 978-4-88317-283-2.

- 土佐民俗学会 (1988). "近世土佐妖怪資料". In 谷川健一編 (ed.). 日本民俗文化資料集成. Vol. 第8巻. 三一書房. pp. 335頁. ISBN 978-4-380-88527-3.

- 柳田國男 (1977). 妖怪談義. 講談社学術文庫. 講談社. pp. 212頁. ISBN 978-4-06-158135-7.

- 国枝春一・広瀬貫之 (May 1940). "美濃揖斐郡徳山村郷土誌". 旅と伝説 (5月号(通巻149号)): 63頁.

- 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. pp. 138頁.

- 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. pp. 51頁.

- 西村市郎右衛門 (1983). 湯沢賢之助 (ed.). 新御伽婢子. 古典文庫. pp. 348頁.

- 水木しげる (1981). 水木しげるの妖怪事典. 東京堂出版. pp. 188頁. ISBN 978-4-490-10149-2.

- 柳田國男監修 民俗学研究所編 (1955). 綜合日本民俗語彙. Vol. 第4巻. 平凡社. pp. 1749頁.

- 『世界原色百科事典』2巻「狐火」項

- 『広辞苑』第二版540項

- 大槻義彦 (1991). 火の玉を見たか. ちくまプリマーブックス. 筑摩書房. pp. 181–193頁. ISBN 978-4-480-04154-8.

- 那谷敏郎 『「魔」の世界』 講談社学術文庫 2003年 ISBN 4-06-159624-1 p.186

References

- 神田左京 (1992). 不知火・人魂・狐火. 中公文庫. 中央公論新社. ISBN 978-4-12-201958-4.

- 高田衛監修 稲田篤信・田中直日編 (1992). 鳥山石燕 画図百鬼夜行. 国書刊行会. ISBN 978-4-336-03386-4.

- 多田克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち. Truth in fantasy. Vol. IV. 新紀元社. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- 寺島良安 (1987). 島田勇雄・竹島淳夫・樋口元巳訳注 (ed.). 和漢三才図会. 東洋文庫. Vol. 8. 平凡社. ISBN 978-4-256-80476-6.

- 根岸鎮衛 (1991). 長谷川強校注 (ed.). 耳嚢. 岩波文庫. Vol. 下. 岩波書店. ISBN 978-4-00-302613-7.