Santa Prisca, Rome

Santa Prisca is a titular church of Rome, on the Aventine Hill, for Cardinal-priests. It is recorded as the Titulus Priscae in the acts of the 499 synod.

| Santa Prisca | |

|---|---|

| Church of Saint Prisca | |

Chiesa di Santa Prisca | |

The facade | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°52′59″N 12°29′02″E | |

| Location | 11 Via di Santa Prisca, Rome |

| Country | Italy |

| Language(s) | Italian |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | santaprisca |

| History | |

| Status | titular church |

| Founded | 12th century |

| Dedication | Saint Prisca |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Carlo Francesco Lombardi |

| Architectural type | Baroque |

| Completed | 1728 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Rome |

Church

It is devoted to Saint Prisca, a 1st-century martyr, whose relics are contained in the altar in the crypt. It was built in the 4th or 5th century over a temple of Mithras. Damaged in the Norman Sack of Rome, the church was restored several times. The current aspect is due to the 1660 restoration, which included a new facade by Carlo Lombardi. In the interior, the columns are the only visible remains of the ancient church. Also a baptismal font allegedly used by Saint Peter is conserved. The frescoes in the crypt, where an altar contains the relics of Saint Prisca, are by Antonio Tempesta. Anastasio Fontebuoni frescoed the walls of the nave with Saints and angels with the instruments of passion. In the sacristy hangs a painting of the Immaculate conception with angels by Giovanni Odazzi, and on the main altar a Baptism of Santa Prisca by Domenico Passignano.

Mithraeum

The Discovery of the Mithraeum

The Mithraeum under Santa Prisca was first discovered in 1934, having been excavated by Augustinian Catholic Fathers who had been in charge of the monastery. Excavations by the Dutch began in 1952–59. The original building was erected in ca. 95 CE and was originally a plot of land purchased by Trajan, who at the time was not yet emperor of Rome.[1] This had also served as Trajan's town house until his death in 117 A.D. One hundred years later, a member of the imperial family took over the building and built a Mithraeum in one part of the basement, while a Christian meeting place was established in the other section.

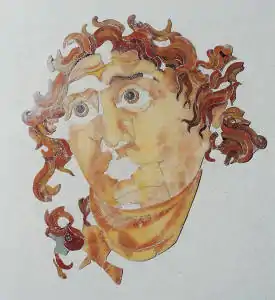

Upon beginning the excavations in 1952, the Dutch cleared away mounds of earth which were thought to have been a sort of trench.[1] During this period, many artifacts were discovered by the Dutch who made a careful record. Some of these discoveries included frescoes, mosaics, remains of various vases, stucco, as well as fragments of mosaic and brick.[1] The original Mithrauem had a central aisle, a niche, and side benches. Fine frescoes were found on the walls of the ancient Mithraeum as well as a stucco sculpture of Mithras the Bull Slayer, one of the main images of the Mithras cult. During the Dutch excavations in the 1950s, pieces of mosaic were found within the newly discovered rooms underneath Santa Prisca. Renovations in 220 yielded a larger central cult room and the addition of new ones while the frescoes were covered with new, more elaborate paintings. The frescoes often included writing underneath or around the work, which would describe what that fresco showed. This is something very unique to the Mithraic temple found at Santa Prisca. These paintings were also important to the development of understanding the Mithraic cult. Along with the typical bull slaying scene so commonly depicted amongst the cult, other paintings depicted different cult rituals. For example, one painting shows a procession of figures wearing masks and different colored tunics holding what has been presumed to be a piece of liturgical equipment.[2] These paintings have been mentioned in the long-standing debate about the admittance of women into the cult. Around 400, the Christians took over the Mithraeum, destroyed it and built Santa Prisca on top of it.

Paintings and Iconography in the Mithraeum of Santa Prisca

The excavations of the Mithraeum by the Dutch in the mid 20th century proved to have found leftover fragments of frescoes. The Mithraeum had been embellished with paintings, and these frescoes, in particular, contain imagery and iconography which depict particular beliefs in the Mithraic cult as well as elements of initiation. One of the frescoes on the left wall within the Mithraeum of the Roman Church includes a depiction of a cult processional towards figures Mithra and Sol, with those participating in the cult holding various objects as they make their way to their deities.[3] Both the left and right walls in the Mithraeum of Santa Prisca have remnants of paintings which depict different scenes and include several figures; however, due to destruction, some of the images are difficult to make out. The left wall of the temple shows several walking male figures, some youthful and full of energy. They are seen in brown and yellow color tunic holding objects like pans, terracotta and glass vessels, even animals like chickens.[1] Another figure in the painting is seen standing, wearing a red tunic and is depicted with a raven face mask and proffering an oblong dish.[1] Other depictions within the frescoes of the Mithraeum include soldiers holding their military bags. Within the Mithraic cult, there is an initiation of seven grades, which are also referred to as the seven planetary grades of salvation. It is thought that this fresco in Santa Prisca is a depiction of the seven grades of initiation, though it is hard to be certain with only the fragmentary evidence that remains. The right wall fresco in the Mithraeum features the seven grades arranged in the exact order (followed by their symbols):

- Corax, Mercury: raven and magic staff.

- Nymphus, Venus: bridal veil.

- Miles, Mars: lance, helmet and bag.

- Leo, Jupiter: shovel, sistrem (sacred rattle) and Jupiters thunderbolts.

- Perses, Luna: crescent moon, scythe and falx.

- Heliodromus, Sol: whip, torch and halo.

- Pater, Saturn: symbols of the father, depicted by the clothes of Mithra, a ring and staff.

The Dutch excavations of M. J. Vermaseren and C. C. Essen in the mid 20th century also revealed there to be paintings in the temples underneath the church. The whole sanctuary was found to have been originally painted by the members of the cult. The Mithraeum's entrance had been stuccoed and painted red, also featuring a painted blue ceiling with stars.[1] Both the temples within the Mithraeum have paintings of an initiate processional and Sol seen with pierced rays for illumination as well as painted remnants which are believed to be fruit baskets and flowers.[1]

The findings of Vermaseren and Essen also found there to be similarities to another Mithreaum in Ostia Antica, a harbor city 19 miles (30 kilometers) from Rome. The architectural analysis suggests that the Mithraeum under the Santa Prisca Church in Rome had undergone construction and was enlarged around the year 220 A.D. Similarities between the two Mithraic temples also suggest that those in the cult who had worked on the Mithraeum in Ostia had helped in the construction and painting of the Mithraeum in Santa Prisca.[1]

Cardinal-protectors

The Cardinal Priest of the Titulus S. Priscae is Justin Francis Rigali, Cardinal Archbishop Emeritus of Philadelphia (US).

Previous Cardinal-Priests include:

- Jacques Fournier, O. Cist. (18 Dec 1327 - 20 Dec 1334) elected Pope Benedict XII

- Zbigniew z Oleśnicy (8 Jan 1440 - 1 Apr 1455)

- Juan de Mella (18 Dec 1456 - 12 Oct 1467)

- Juan de Castro (24 Feb 1496 - 29 Sep 1506)

- Niccolò Fieschi (5 Oct 1506 - 15 Jun 1524)

- Andrea della Valle (27 Mar 1525 - 3 Aug 1534)

- Gianvincenzo Carafa (23 Jul 1537 - 28 Nov 1537)

- Rodolfo Pio (28 Nov 1537 - 24 Sep 1543)

- Bartolomeo Guidiccioni (24 Sep 1543 - 4 Nov 1549)

- Federico Cesi (28 Feb 1550 - 20 Sep 1557)

- Giovanni Angelo de’ Medici (20 Sep 1557 - 25 Dec 1559) elected Pope Pius IV

- Jean de Bertrand (16 Jan 1560 - 13 Mar 1560)

- Jean Suau (26 Apr 1560 - 29 Apr 1566)

- Bernardo Salviati (15 May 1566 - 6 May 1568)

- Antoine Perrenot de Granvella (14 May 1568 - 10 Feb 1570)

- Stanislaw Hosius (Hozjusz) (10 Feb 1570 - 9 Jun 1570)

- Girolamo di Corregio (9 Jun 1570 - 3 Jul 1570)

- Giovanni Francesco Gàmbara (3 Jul 1570 - 17 Oct 1572)

- Alfonso Gesualdo di Conza (Gonza) (17 Oct 1572 - 9 Jul 1578)

- Flavio Orsini (9 Jul 1578 - 16 May 1581)

- Pedro de Deza (9 Jan 1584 - 20 Apr 1587)

- Girolamo Simoncelli (15 Jan 1588 - 30 Mar 1598)

- Benedetto Giustiniani (17 Mar 1599 - 17 Aug 1611)

- Bonifazio Bevilacqua Aldobrandini (31 Aug 1611 - 7 Jan 1613)

- Carlo Conti (7 Jan 1613 - 3 Dec 1615)

- Tiberio Muti (11 Jan 1616 - 14 Apr 1636)

- Francesco Adriano Ceva (31 Aug 1643 - 12 Oct 1655)

- Giulio Gabrielli (6 Mar 1656 - 18 Jul 1667)

- Carlo Pio di Savoia (14 Nov 1667 - 28 Jan 1675)

- Alessandro Crescenzi, C.R.S. (15 Jul 1675 - 8 May 1688)

- Marcello Durazzo (14 Nov 1689 - 21 Feb 1701)

- Giuseppe Archinto (14 Mar 1701 - 9 Apr 1712)

- Francesco Maria Casini, O.F.M. Cap. (11 Jul 1712 - 14 Feb 1719)

- Giovanni Battista Salerni, S.J. (16 Sep 1720 - 20 Feb 1726)

- Luis Antonio Belluga y Moncada, C.O. (20 Feb 1726 - 16 Dec 1737)

- Pierluigi Carafa (Jr.) (16 Dec 1737 - 16 Sep 1740)

- Silvio Valenti Gonzaga (16 Sep 1740 - 15 May 1747)

- Mario Mellini (15 May 1747 - 1 Apr 1748)

- Ludovico Merlini (21 Jul 1760 - 12 Apr 1762)

- Francesco Mantica (23 Feb 1801 - 13 Apr 1802)

- Francesco Maria Pandolfi Alberici (2 Jul 1832 - 3 Jun 1835)

- Giuseppe Alberghini (6 Apr 1835 - 30 Sep 1847)

- Miguel García Cuesta (21 May 1862 - 14 Apr 1873)

- Tommaso Maria Martinelli, O.E.S.A. (17 Sep 1875 - 24 Mar 1884)

- Michelangelo Celesia, O.S.B. (13 Nov 1884 - 25 Nov 1887)

- Luigi Sepiacci, O.E.S.A. (17 Dec 1891 - 26 Apr 1893)

- Domenico Ferrata (3 Dec 1896 - 10 Oct 1914)

- Vittorio Ranuzzi de' Bianchi (7 Dec 1916 - 16 Feb 1927)

- Charles-Henri-Joseph Binet (22 Dec 1927 - 15 Jul 1936)

- Adeodato Giovanni Piazza, O.C.D. (13 Dec 1937 - 14 Mar 1949)

- Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli (12 Jan 1953 - 28 Oct 1958) elected Pope John XXIII

- Giovanni Urbani (15 Dec 1958 - 19 Mar 1962)

- José da Costa Nunes (19 Mar 1962 - 29 Nov 1976)

- Giovanni Benelli (27 Jun 1977 - 26 Oct 1982)

- Alfonso López Trujillo (2 Feb 1983 - 17 Nov 2001)

Footnotes

- M.J. Vermaseren and C. C. Van Essen. The Excavations in the Mithraeum of the Church of Santa Prisca in Rome. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1965.

- Griffith, Alison. "Completing the Picture: Women and the Female Principle in the Mithraic Cult." Numen Vol. 53, No. 1. Brill: 2006

- Groh, Dennis (1967). Mithraism in Ostia. Sacramento State University Library: Northwestern University Press.

References

- David, Jonathan (2000). "The Exclusion of Women in the Mithraic Mysteries: Ancient or Modern?". Numen 47 (2): 121–141. doi:10.1163/156852700511469