SOX 404 top–down risk assessment

In financial auditing of public companies in the United States, SOX 404 top–down risk assessment (TDRA) is a financial risk assessment performed to comply with Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX 404). Under SOX 404, management must test its internal controls; a TDRA is used to determine the scope of such testing. It is also used by the external auditor to issue a formal opinion on the company's internal controls. However, as a result of the passage of Auditing Standard No. 5, which the SEC has since approved, external auditors are no longer required to provide an opinion on management's assessment of its own internal controls.

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

Detailed guidance about performing the TDRA is included with PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5 (Release 2007-005 "An audit of internal control over financial reporting that is integrated with an audit of financial statements")[1] and the SEC's interpretive guidance (Release 33-8810/34-55929) "Management's Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting".[2][3] This guidance is applicable for 2007 assessments for companies with 12/31 fiscal year-ends. The PCAOB release superseded the existing PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2, while the SEC guidance is the first detailed guidance for management specifically. PCAOB reorganized the auditing standards as of December 31, 2017, with the relevant SOX guidance now included under AS2201: An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That is Integrated with An Audit of Financial Statements.[4]

The language used by the SEC chairman in announcing the new guidance was very direct: "Congress never intended that the 404 process should become inflexible, burdensome, and wasteful. The objective of Section 404 is to provide meaningful disclosure to investors about the effectiveness of a company's internal controls systems, without creating unnecessary compliance burdens or wasting shareholder resources."[5] Based on the 2007 guidance, SEC and PCAOB directed a significant reduction in costs associated with SOX 404 compliance, by focusing efforts on higher-risk areas and reducing efforts in lower-risk areas.

TDRA is a hierarchical framework that involves applying specific risk factors to determine the scope and evidence required in the assessment of internal control. Both the PCAOB and SEC guidance contain similar frameworks. At each step, qualitative or quantitative risk factors are used to focus the scope of the SOX404 assessment effort and determine the evidence required. Key steps include:

- identifying significant financial reporting elements (accounts or disclosures)

- identifying material financial statement risks within these accounts or disclosures

- determining which entity-level controls would address these risks with sufficient precision

- determining which transaction-level controls would address these risks in the absence of precise entity-level controls

- determining the nature, extent, and timing of evidence gathered to complete the assessment of in-scope controls

Management is required to document how it has interpreted and applied its TDRA to arrive at the scope of controls tested. In addition, the sufficiency of evidence required (i.e., the timing, nature, and extent of control testing) is based upon management (and the auditor's) TDRA. As such, TDRA has significant compliance cost implications for SOX404.

Method

The guidance is principles-based, providing significant flexibility in the TDRA approach. There are two major steps: 1) Determining the scope of controls to include in testing; and 2) Determining the nature, timing and extent of testing procedures to perform.

Determining scope

The key SEC principle related to establishing the scope of controls for testing may be stated as follows: "Focus on controls that adequately address the risk of material misstatement." This involves the following steps:

Determine significance and misstatement risk for financial reporting elements (accounts and disclosures)

Under the PCAOB AS 5 guidance, the auditor is required to determine whether an account is "significant" or not (i.e., yes or no), based on a series of risk factors related to the likelihood of financial statement error and magnitude (dollar value) of the account. Significant accounts and disclosures are in-scope for assessment, so management typically includes this information in its documentation and generally performs this analysis for review by the auditor. This documentation may be referred to in practice as the "significant account analysis." Accounts with large balances are generally presumed to be significant (i.e., in-scope) and require some type of testing.

New under the SEC guidance is the concept of also rating each significant account for "misstatement risk" (low, medium, or high), based on similar factors used to determine significance. The misstatement risk ranking is a key factor used to determine the nature, timing, and extent of evidence to be obtained. As risk increases, the expected sufficiency of testing evidence accumulated for controls related to significant accounts increases (see section below regarding testing & evidence decisions).

Both significance and misstatement risk are inherent risk concepts, meaning that conclusions regarding which accounts are in-scope are determined before considering the effectiveness of controls.

Identify financial reporting objectives

Objectives help set the context and boundaries in which risk assessment occurs. The COSO Internal Control-Integrated Framework, a standard of internal control widely used for SOX compliance, states: "A precondition to risk assessment is the establishment of objectives..." and "Risk assessment is the identification and analysis of relevant risks to achievement of the objectives." The SOX guidance states several hierarchical levels at which risk assessment may occur, such as entity, account, assertion, process, and transaction class. Objectives, risks, and controls may be analyzed at each of these levels. The concept of a top-down risk assessment means considering the higher-levels of the framework first, to filter from consideration as much of the lower-level assessment activity as possible.

There are many approaches to top-down risk assessment. Management may explicitly document control objectives, or use texts and other references to ensure their risk statement and control statement documentation is complete. There are two primary levels at which objectives (and also controls) are defined: entity-level and assertion level.

An example of an entity-level control objective is: "Employees are aware of the Company's Code of Conduct." The COSO 1992–1994 Framework defines each of the five components of internal control (i.e., Control Environment, Risk Assessment, Information & Communication, Monitoring, and Control Activities). Evaluation suggestions are included at the end of key COSO chapters and in the "Evaluation Tools" volume; these can be modified into objective statements.

An example of an assertion-level control objective is "Revenue is recognized only upon the satisfaction of a performance obligation." Lists of assertion-level control objectives are available in most financial auditing textbooks. Excellent examples are also available in AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 110 (SAS 110) [6] for the inventory process. SAS 106 includes the latest guidance on financial statement assertions.[7]

Control objectives may be organized within processes, to help organize the documentation, ownership and TDRA approach. Typical financial processes include expense & accounts payable (purchase to payment), payroll, revenue and accounts receivable (order to cash collection), capital assets, etc. This is how most auditing textbooks organize control objectives. Processes can also be risk-ranked.

COSO issued revised guidance in 2013 effective for companies with year-end dates after December 15, 2014. This essentially requires control statements to be referenced to 17 "principles" beneath the five COSO "components." There are approximately 80 "points of focus" that can be evaluated specifically against the controls of the company, to form a conclusion about the 17 principles (i.e., each principle has several relevant points of focus). Most of the principles and points of focus relate to entity-level controls. As of June 2013 the approaches used in practice were in the early stages of development.[8] One approach would be to add the principles and points of focus as criteria within a database and reference each to the relevant controls that address them.

Identify material risks to the achievement of the objectives

One definition of risk is anything that can interfere with the achievement of an objective. A risk statement is an expression of "what can go wrong." Under the 2007 guidance (i.e., SEC interpretive guidance and PCAOB AS5), those risks that inherently have a "reasonably possible" likelihood of causing a material error in the account balance or disclosure are the material misstatement risks ("MMR"). Note that this is a slight amendment to the "more than remote" likelihood language of PCAOB AS2, intended to limit the scope to fewer, more critical material risks and related controls.

An example of a risk statement corresponding to the above assertion level control objective might be: "The risk that revenue is recognized before the delivery of products and services." Note that this reads very similarly to the control objective, only stated in the negative.

Management develops a listing of MMR, linked to the specific accounts and/or control objectives developed above. MMR may be identified by asking the question: "What can go wrong related to the account, assertion or objective?" MMR may arise within the accounting function (e.g., regarding estimates, judgments, and policy decisions) or the internal and external environment (e.g., corporate departments that feed the accounting department information, economic and stock market variables, etc.) Communication interfaces, changes (people, process or systems), fraud vulnerability, management override of controls, incentive structure, complex transactions, and degree of judgment or human intervention involved in processing are other high-risk topics.

In general, management considers questions such as: What is really difficult to get right? What accounting problems have we had in the past? What has changed? Who might be capable or motivated to commit fraud or fraudulent financial reporting? As a high percentage of financial frauds historically have involved the overstatement of revenue, such accounts typically merit additional attention. AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 109 (SAS 109)[9] also provides helpful guidance regarding financial risk assessment.

Under the 2007 guidance, companies are required to perform a fraud risk assessment and assess related controls. This typically involves identifying scenarios in which theft or loss could occur and determining if existing control procedures effectively manage the risk to an acceptable level.[10] The risk that senior management might override important financial controls to manipulate financial reporting is also a key area of focus in the fraud risk assessment.[11]

In practice, many companies combine the objective and risk statements when describing MMR. These MMR statements serve as a target, focusing efforts to identify mitigating controls.

Identify controls that address the material misstatement risks (MMR)

For each MMR, management determines which control (or controls) address the risk "sufficiently" and "precisely" (PCAOB AS#5) or "effectively" (SEC Guidance) enough to mitigate it. The word "mitigate" in this context means the control (or controls) reduces the likelihood of material error presented by the MMR to a "remote" probability. This level of assurance is required because a material weakness must be disclosed if there is a "reasonably possible" or "probable" possibility of a material misstatement of a significant account. Even though multiple controls may bear on the risk, only those that address it as defined above are included in the assessment. In practice, these are called the "in-scope" or "key" controls that require testing.

The SEC Guidance defines the probability terms as follows, per FAS5 Accounting for Contingent Liabilities:

- "Probable: The future event or events are likely to occur."

- "Reasonably possible: The chance of the future event or events occurring is more than remote but less than likely."

- "Remote: The chance of the future event or events occurring is slight."[12]

Judgment is typically the best guide for selecting the most important controls relative to a particular risk for testing. PCAOB AS5 introduces a three-level framework describing entity-level controls at varying levels of precision (direct, monitoring, and indirect.) As a practical matter, control precision by type of control, in order of most precise to least, may be interpreted as:

- Transaction-specific (transaction-level) – Authorization or review (or preventive system controls) related to specific, individual transactions;

- Transaction summary (transaction-level) – Review of reports listing individual transactions;

- Period-end reporting (account-level) – Journal entry review, account reconciliations or detailed account analysis (e.g., utility spending per store);

- Management review controls (direct entity level) – Fluctuation analyses of income statement accounts at varying levels of aggregation or monthly reporting package containing summarized financial and operational information;

- Monitoring controls (monitoring entity level) - Self-assessment and internal audit reviews to verify controls are designed and implemented effectively; and

- Indirect (indirect entity level) - Controls that are not linked to specific transactions, such as the control environment (e.g., tone set by management and hiring practices).

It is increasingly difficult to argue that reliance upon controls is reasonable in achieving assertion-level objectives as one travels along this continuum from most precise to least, and as risk increases. A combination of type 3-6 controls above may help reduce the number of type 1 & 2 controls (transaction-level) that require assessment for particular risks, especially in lower-risk, transaction-intensive processes.

Under the 2007 guidance, it appears acceptable to place significantly more reliance on the period-end controls (i.e., review of journal entries and account reconciliations) and management review controls than in the past, effectively addressing many of the material misstatement risks and enabling either: a) the elimination of a significant number of transactional controls from the prior-year's scope of testing; or b) reducing related evidence obtained. The number of transaction-level controls may be reduced significantly, particularly for lower-risk accounts.

Considerations in testing and evidence decisions

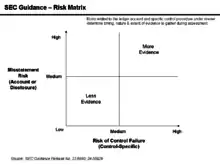

The key SEC principle regarding evidence decisions can be summarized as follows: "Align the nature, timing and extent of evaluation procedures on those areas that pose the greatest risks to reliable financial reporting." The SEC has indicated that the sufficiency of evidence required to support the assessment of specific MMR should be based on two factors: a) Financial Element Misstatement Risk ("Misstatement Risk") and b) Control Failure Risk. These two concepts together (the account- or disclosure-related risks and control-related risks) are called "Internal Control over Financial Reporting Risk" or "ICFR" risk. A diagram was included in the guidance (shown in this section) to illustrate this concept; it is the only such diagram, which indicates the emphasis placed on it by the SEC. ICFR risk should be associated with the in-scope controls identified above and may be part of that analysis. This involves the following steps:

Link each key control to the "Misstatement Risk" of the related account or disclosure

Management assigned a misstatement risk ranking (high, medium or low) for each significant account and disclosure as part of the scoping assessment above. The low, medium, or high ranking assessed should also be associated with the risk statements and control statements related to the account. One way of accomplishing this is to include the ranking within the risk statement and control statement documentation of the company. Many companies use databases for this purpose, creating data fields within their risk and control documentation to capture this information.

Rate each key control for "control failure risk (CFR)" and "ICFR risk"

CFR is applied at the individual control level, based on factors in the guidance related to complexity of processing, manual vs. automated nature of the control, judgment involved, etc. Management fundamentally asks the question: "How difficult is it to execute this control properly each and every time?"

With account misstatement risk and CFR defined, management can then conclude on ICFR risk (low, medium, or high) for the control. ICFR is the key risk concept used in evidence decisions.

The ICFR rating is captured for each control statement. Larger companies typically have hundreds of significant accounts, risk statements, and control statements. These have a "many to many" relationship, meaning risks can apply to multiple accounts and controls can apply to multiple risks.

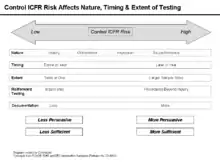

Consider the impact of risk on the timing, nature, and extent of testing

The guidance provides flexibility in the timing, nature and extent of evidence based on the interaction of Misstatement Risk and Control Failure Risk (together, ICFR Risk). These two factors should be used to update the "Sampling and Evidence Guide" used by most companies. As these two risk factors increase, the sufficiency of evidence required to address each MMR increases.

Management has significant flexibility regarding the following testing and evidence considerations, in the context of the ICFR risk related to a given control:

- Extent (sample size): The sample size increases proportionally to ICFR risk.

- Nature of evidence: Inquiry, observation, inspection and re-performance are the four evidence types, listed in order of sufficiency. Evidence beyond inquiry, typically inspection of documents, is required for tests of control operating effectiveness. Re-performance evidence would be expected for the highest risk controls, such as in the period-end reporting process.

- Nature of the control (manual vs. automated): For fully automated controls, either a sample size of one or a "benchmarking" test strategy may be used. If IT general controls related to change management are effective and the fully automated control has been tested in the past, annual testing is not required. The benchmark must be periodically established.

- Scope of roll-forward testing required: As risk increases, roll-forward testing is increasingly likely to be necessary to extend the effect of interim testing to year-end. Lower-risk controls presumably do not require roll-forward testing.

Pervasive factors that also affect the evidence considerations above include:

- Overall strength of entity-level controls, particularly the control environment: Strong entity-level controls act as a pervasive "counter-weight" to risk across the board, reducing the sufficiency of evidence required in lower-risk areas and supporting the spirit of the new guidance in terms of reducing overall effort.

- Cumulative knowledge from prior assessments regarding particular controls: If particular processes and controls have a history of working effectively, the extent of evidence required in lower-risk areas can be reduced.

Consider risk, objectivity, and competence in testing decisions

Management has significant discretion in who performs its testing. The SEC guidance indicates that the objectivity of the person testing a given control should increase proportionally to the ICFR risk related to that control. Therefore, techniques such as self-assessment are appropriate for lower-risk areas, while internal auditors (or the equivalent) generally should test higher-risk areas. An intermediate technique in practice is "quality assurance," where manager A tests manager B's work, and vice versa.

The external auditors ability to rely on management's testing follows similar logic. Reliance is proportional to the competence and objectivity of the management person that completed the testing, also in the context of risk. For the highest risk areas, such as the control environment and period-end reporting process, internal auditors or compliance teams are likely the best choices to perform testing, if a significant degree of reliance is expected from the external auditor. The ability of the external auditor to rely on management's assessment is a major cost factor in compliance.

Strategies for efficient SOX 404 assessment

There are a variety of specific opportunities to make the SOX 404 assessment as efficient as possible.[13][14] Some are more long-term in nature (such as centralization and automation of processing) while others can be readily implemented. Frequent interaction between management and the external auditor is essential to determining which efficiency strategies will be effective in each company's particular circumstances and the extent to which control scope reduction is appropriate.

Centralization and automation

Centralize: Using a shared service model in key risk areas enables multiple locations to be treated as one for testing purposes. Shared service models are typically used for payroll and accounts payable processes, but can be applied to many types of transaction processing. According to a recent survey by Finance Executives International, decentralized companies had dramatically higher SOX compliance costs than centralized companies.[15]

Automate and benchmark: Key fully automated IT application controls have minimal sample size requirements (usually one, as opposed to as many as 30 for manual controls) and may not have to be tested directly at all under the benchmarking concept. Benchmarking allows fully automated IT application controls to be excluded from testing if certain IT change management controls are effective. For example, many companies rely heavily on manual interfaces between systems, with spreadsheets created for downloading and uploading manual journal entries. Some companies process thousands of such entries each month. By automating manual journal entries, both labor and SOX assessment costs may be dramatically reduced. In addition, the reliability of financial statements is improved.

Overall assessment approach

Review testing approach and documentation: Many companies or external audit firms mistakenly attempted to impose generic frameworks over unique transaction-level processes or across locations. For instance, most of the COSO Framework elements represent indirect entity-level controls, which should be tested separately from transactional processes. In addition, IT security controls (a subset of ITGC) and shared service controls can be placed in separate process documentation, enabling more efficient assignment of test responsibility and removing redundancy across locations. Testing the key journal entries and account reconciliations as separate efforts enables additional efficiency and focus to be brought to these critical controls.

Rely on direct entity-level controls: The guidance emphasizes identifying which direct entity-level controls, particularly the period-end process and certain monitoring controls, are sufficiently precise to remove assertion-level (transactional) controls from scope. The key is to determine which combination of entity-level and assertion-level controls address particular MMR.

Minimize roll-forward testing: Management has more flexibility under the new guidance to extend the effective date of testing performed during mid-year ("interim") periods to the year-end date. Only the higher risk controls will likely require roll-forward testing under the new guidance. PCAOB AS5 indicates that inquiry procedures, regarding whether changes in the control process occurred between the interim and year-end period, may be sufficient in many cases to limit roll-forward testing.

Revisit scope of locations or business units assessed: This is a complex area requiring substantial judgment and analysis. The 2007 guidance focused on specific MMR, rather than dollar magnitude in determining the scope and sufficiency of evidence to be obtained at decentralized units. The interpretation (common under the pre-2007 guidance) that a unit or group of units was material and therefore a large number of controls across multiple processes require testing irrespective of risk, has been superseded. Where account balances from single units or groups of similar units are a material portion of the consolidated account balance, management should carefully consider whether MMR may exist in a particular unit. Testing focused on just the controls related to the MMR should then be performed. Monitoring controls, such as detailed performance review meetings with robust reporting packages, should also be considered to limit transaction-specific testing.

IT assessment approach

Focus IT general control (ITGC) testing: ITGC are not included in the definition of entity-level controls under the SEC or PCAOB guidance. Therefore, ITGC testing should be performed to the extent it addresses specific MMR. By nature, ITGC enables management to place reliance on fully automated application controls (i.e., those that operate without human intervention) and IT-dependent controls (i.e., those that involve the review of automatically generated reports). Focused ITGC testing is merited to support the control objectives or assertions that fully automated controls have not been changed without authorization and that control reporting generated is both accurate and complete. Key ITGC focus areas therefore likely to be critical include: change management procedures applied to specific financial system implementations during the period; change management procedures sufficient to support a benchmarking strategy; and periodic monitoring of application security, including separation of duties.

PCAOB guidance subsequent to 2007

The PCAOB issues "Staff Audit Practice Alerts" (SAPA) periodically that "highlight new, emerging or otherwise noteworthy circumstances that may affect how auditors conduct audits under the existing requirements of the standards..." Under SAPA #11 Considerations for Audits of Internal Control over Financial Reporting (October 24, 2013), the PCAOB discussed significant audit practice issues regarding ICFR assessment. These included, among other topics:

- System-generated reports ("Information provided by the entity" or "IPE"): Requirements that auditors (and by proxy management) obtain additional evidence that fully automated reports and manual queries used as control inputs are accurate and complete.

- Entity-level controls and management review controls: Excessive reliance was sometimes placed on entity-level controls and management review controls (similar conceptually to period-end controls), which were insufficiently precise to reduce the risk of material misstatement to the "remote" level. SAPA #11 provides additional criteria to assist in this evaluation of precision.

- Criteria for investigation: Auditors did not always obtain sufficient evidence that management's controls were executed effectively where unusual variation outside of specified tolerances was noted. For example, management may have signed a control report saying it was reviewed but provided no other documentation of investigation, despite some unusual activity on the report. SAPA #11 states: "Verifying that a review was signed-off provides little or no evidence by itself about the control's effectiveness."[16]

SAPA #11 may translate into more work for management teams, which may be required by auditors to retain evidence that these reports and queries were accurate and complete. Further, management may be required to retain additional evidence of investigation where detective control report amounts contain transactions or trends outside of predefined tolerance ranges.

References

- PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5

- SEC Interpretive Guidance

- SEC List of SOX Guidance

- PCAOB AS2201 An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting that is Integrated with an Audit of Financial Statements-December 31, 2017

- SEC Press Release 2007-101

- AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 110

- AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 106

- COSO-J. Stephen McNally-The 2013 COSO Framework & SOX Compliance

- AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 109

- PWC – Elements of an Anti-Fraud Program

- AICPA Management Override Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- FASB: Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No.5 - March 1975

- Deloitte-Touche Lean and Balanced

- E&Y Paper "The New 404 Balancing Act"

- FEI Survey Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- PCAOB Staff Audit Practice Alert #11-October 24, 2013