STS-41

STS-41 was the 36th Space Shuttle mission and the eleventh mission of the Space Shuttle Discovery. The four-day mission had a primary objective of launching the Ulysses probe as part of the "International Solar Polar Mission" (ISPM).

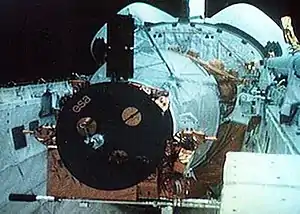

Ulysses and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) in the payload bay of Discovery | |

| Names | Space Transportation System-36 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Ulysses spacecraft deployment |

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1990-090A |

| SATCAT no. | 20841 |

| Mission duration | 4 days, 2 hours, 10 minutes, 4 seconds (achieved) |

| Distance travelled | 2,747,866 km (1,707,445 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 66 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 117,749 kg (259,592 lb) |

| Landing mass | 89,298 kg (196,868 lb) |

| Payload mass | 15,362 kg (33,867 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | October 6, 1990, 11:47:15 UTC |

| Rocket | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch site | Kennedy Space Center, LC-39B |

| Contractor | Rockwell International |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | October 10, 1990, 13:57:19 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Air Force Base, Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 300 km (190 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 307 km (191 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.45° |

| Period | 90.60 minutes |

| Instruments | |

| |

STS-41 mission patch  Bruce E. Melnick, Robert D. Cabana, Thomas Akers, Richard N. Richards, William Shepherd are pictured in front of the T-38 jet trainer | |

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Richard N. Richards Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Robert D. Cabana First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Bruce E. Melnick First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | William Shepherd Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Thomas Akers First spaceflight | |

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Richards | Richards | |

| S2 | Cabana | Cabana | |

| S3 | Melnick | Akers | |

| S4 | Shepherd | Shepherd | |

| S5 | Akers | Melnick |

Mission highlights

Discovery lifted off on October 6 1990 at 7:47:16 a.m. EDT. Liftoff occurred 12 minutes after a two-and-a-half-hour launch window opened that day at 7:35 a.m. EDT. STS-41 featured the heaviest payload to date; Discovery weighed 117,749 kg (259,592 lb).[2]

The primary payload was the European Space Agency (ESA)-built Ulysses spacecraft to explore the polar regions of Sun. Attached to Ulysses were two upper stages, the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) and a mission-specific Payload Assist Module-S (PAM-S), combined for first time to send Ulysses toward an out-of-ecliptic trajectory. Other payloads and experiments included the Shuttle Solar Backscatter Ultraviolet (SSBUV) experiment, INTELSAT Solar Array Coupon (ISAC), Chromosome and Plant Cell Division Experiment (CHROMEX), Voice Command System (VCS), Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE), Investigations into Polymer Membrane Processing (IPMP), Physiological Systems Experiment (PSE), Radiation Monitoring Experiment III (RME III), Shuttle Student Involvement Program (SSIP) and Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS).

Six hours after Discovery's launch, Ulysses was deployed from the payload bay. Ulysses, a joint project between the European Space Agency and NASA, was the first spacecraft to study the Sun's polar regions. Its voyage to the Sun began with a sixteen month trip to Jupiter where the planet's gravitational energy was used to fling Ulysses southward out of the orbital plane of the planets and on toward a solar south pole passage in 1994. The spacecraft crossed back over the orbital plane and made a solar north pole passage in 1995. By the time Discovery touched down at Edwards Air Force Base, California, Ulysses had already traversed 1,600,000 km (990,000 mi) on its five-year mission.

With Ulysses on its way, the STS-41 crew began an ambitious schedule of science experiments. Flowering plant samples were grown in the CHROMEX-2 module in a Kennedy Space Center and Stony Brook University experiment. An earlier version of the experiment flown on STS-29 revealed chromosome damage in root tip cells but no damage to control plants on Earth. By studying plant samples carried on Discovery, researchers hoped to determine how the genetic material in the root cells respond to microgravity. The information gained was of importance to future space travelers on long-term expeditions, researchers on the planned Space Station Freedom, and may contribute to advances in intensive farming practices on Earth.

Understanding fire behavior in microgravity was part of the continuing research to improve Space Shuttle safety. In a specially designed chamber, called the Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE), a strip of paper was burned and filmed to gain an understanding of the development of flame and its movement in the absence of convection currents. This experiment was sponsored by the Lewis Research Center (LeRC) and Mississippi State University.

Atmospheric ozone depletion is an environmental problem of worldwide concern. At the time, NASA's Nimbus 7 satellite and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS) satellites provided daily data to permit researchers to detect ozone trends. The Shuttle Solar Backscatter Ultraviolet (SSBUV) instrument, from the Goddard Space Flight Center, carried an ozone detector instrument identical to those on the satellites. By comparing Discovery's measurements with coordinated satellite observations, scientists were able to calibrate their satellite instruments to insure the most accurate readings possible.

In 1990, a commercial expendable launch vehicle stranded an INTELSAT VI communications satellite in low Earth orbit. Before STS-41, NASA was evaluating a possible Shuttle rescue mission in 1992. In preparation for this rescue, solar arrays, similar to those on the satellite, were exposed to the conditions of low orbit to determine if they were in any way altered by the atomic oxygen present. When the returned arrays were closely examined, it was found that the arrays were not significantly damaged. Based on this finding, NASA went ahead and carried out STS-49 in 1992.

Until STS-41, previous research had shown that during the process of adapting to microgravity, animals and humans experienced loss of bone mass, cardiac deconditioning, and after prolonged periods (over 30 days), developed symptoms similar to that of terrestrial disuse osteoporosis. The goal of the STS-41 Physiological Systems Experiment (PSE), sponsored by the Ames Research Center and Pennsylvania State University's Center for Cell Research, was to determine if pharmacological treatments would be effective in reducing or eliminating some of these disorders. Proteins, developed by Genentech of San Francisco, California, were administered to eight rats during the flight while another eight rats accompanying them on the flight did not receive the treatment.

The Investigations into Polymer Membrane Processing (IPMP) experiment was conducted to determine the role convection currents play in membrane formation. Membranes are used in commercial applications for purification of medicines, kidney dialysis, and water desalination. This experiment was sponsored in part by the Battelle Advanced Materials Center for the Commercial Development of Space in Columbus, Ohio.

During open periods in the STS-41 crew schedule, the astronauts video taped a number of demonstrations as part of an effort to create an educational video tape for middle school level students. The tape was later distributed nationwide through NASA's Teacher Resource Center network.

The astronauts evaluated the suitability of graphical user interfaces. Previous shuttle crews used Grid Systems laptop computers with command-line interfaces. The evaluation used mostly commercially available hardware and software, including a Macintosh Portable laptop. The astronauts found the Portable's trackball did not work well in weightlessness. The evaluation was continued on STS-43, this time using a Macintosh Portable with a modified trackball.[3]

Additional crew activities included experimenting with a voice command system (VCS) to control onboard television cameras and monitoring ionizing radiation exposure to the crew within the orbiter cabin.

On October 10, 1990, at 6:57:19 a.m. PDT, Discovery landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on runway 22. Rollout distance was 2,523 m (8,278 ft) and the rollout time was 49 seconds (including a braking test). Discovery was returned to Kennedy Space Center on October 16, 1990.

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Project Gemini, which was first used to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by their families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[4]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer | Played for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 |

"Rise and Shine, Discovery!" | a group of Boeing employees | Ulysses |

| Day 3 |

"Semper Paratus" | The Coast Guard Band | Bruce Melnick |

| Day 4 |

Fanfare for the Common Man | Aaron Copland | |

| Day 5 |

"The Highwayman" | The Highwaymen |

See also

References

- "STS-41". Spacefacts. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- Chowdhury, Abdul (June 10, 2020). "STS-41". Life Science Data Archive. NASA. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- Lewis, Peter H. (August 12, 1991). "SHUTTLE MISSION PUTS COMPUTERS TO THE TEST NASA makes Grid, Macintosh space-friendly". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- Fries, Colin (June 25, 2007). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links

- NASA mission summary Archived July 28, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- STS-41 Video Highlights Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)