Sack of Shamakhi

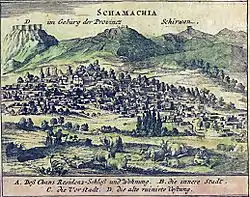

The sack of Shamakhi took place on 18 August 1721, when rebellious Sunni Lezgins, within the declining Safavid Empire, attacked the capital of Shirvan province, Shamakhi (in present-day Azerbaijan Republic).[1][2] The initially successful counter-campaign was abandoned by the central government at a critical moment and with the threat then left unchecked, Shamakhi was taken by 15,000 Lezgin tribesmen, its Shia population massacred, and the city ransacked.

The deaths of Russian merchants within Shamakhi were subsequently used as a casus belli for the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723, leading to the cessation of trade between Iran and Russia and the designation of Astrakhan as the new terminus on the Volga trade route.

Background

By the first decade of the 18th century, the once-prosperous Safavid realm was in a state of heavy decline, with insurrections in numerous parts of its domains.[3] The king, Soltan Hoseyn, was a weak ruler, and although personally inclined to be more humane, flexible, and relaxed than his chief mullah, he went along with the recommendations of his advisers regarding important state decisions.[4] He reigned as a "stationary monarch", preferring, apart from the occasional hunting party, to be inside or near the capital of Isfahan at all times, invisible to all "but the most intimate of courtiers".[3] Having seen not much more of the world than the harem walls, he had quickly fallen under the spell of the leading ulama, most notably Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi.[3] Majlesi, who had already gained considerable political power during the reign of Soltan Hoseyn's predecessor Suleiman I (r. 1666–1694), instigated the persecutions directed towards Safavid Iran's Sunni and Sufi inhabitants, as well as its non-Muslim religious minorities, namely Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians.[3][5] Though the Christians, mainly represented by the Armenians, suffered less than other groups, they were also targeted from time to time.[5] According to historian Roger Savory, even though Soltan Hoseyn did not show personal hostility towards Christians, he was persuaded by the clergy (Majlisi in particular), who had great influence over him, to issue "unjust and intolerant decrees".[5] The tense religious atmosphere in the late Safavid era would prove to be a significant factor in the revolts by Sunni adherents from various places within the empire.[4] As the historian Michael Axworthy notes: "The clearest example was the revolt in Shirvan, where Sunni religious men had been killed, religious books destroyed and Sunni mosques turned into stables".[4]

The Sunni population in the northwestern domains of the Safavids, comprising Shirvan and Daghestan, felt the burden of the Shia persecution during Soltan Hoseyn's reign.[5] 1718 saw an intensification of the Lezgin incursions into Shirvan,[6] rumoured, according to historian Rudi Matthee, to have been incited by then grand vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani (1716–1720).[6] Russia's ambassador to Safavid Iran, Artemy Volynsky, who was in Shamakhi in 1718,[7] reported that, because local officials considered the grand vizier "an infidel", they considered his orders invalid and even questioned the king's authority.[7] Florio Beneveni, an Italian in the Russian diplomatic service, insisted that Shamakhi's inhabitants were ready to revolt against the government for "extorting large sums of money from them".[7] The marauding raids, incursions, and pillages nevertheless carried on; in April of the same year, the Lezgins took the village of Ak Tashi (located near Nizovoi[lower-alpha 1]), but not before abducting a number of its inhabitants and plundering a caravan of 40 people on the road to Shamakhi.[6] After these events, numerous additional reports in relation to the rebels are reported.[6]

Attack and sack

By early May 1718, some 17,000 Lezgin tribesmen had reached a distance of 20 kilometres (12 mi) from Shamakhi, occupying themselves with looting settlements in Shamakhi's surrounding areas.[6] In 1719, the Iranian government decided to send the sepahsalar Hoseynqoli Khan (Vakhtang VI of Kartli) to Georgia with the task of confronting the Lezgin rebellion.[7] Assisted by the ruler of neighboring Kakheti, as well as the beglarbeg of Shirvan, Hoseynqoli Khan moved to Daghestan and made significant progress in putting a halt to the Lezgins.[7] However, in the winter of 1721, at a crucial moment in the campaign, he was recalled.[7] The order, which came after the fall of grand vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani, was made at the instigation of the eunuch faction within the royal court, who had persuaded the shah that a successful end of the campaign would do the Safavid realm more harm than good. In their view, it would enable Vakhtang, the Safavid vali, to form an alliance with Russia with an eye to conquering Iran.[7] Around the same time, in August 1721, Soltan Hoseyn ordered Daud Beg (probably Hadji-Dawud), a rebel mountaineer chieftain of the Lezgins and a Sunni cleric, to be released from prison in the Safavid city of Derbent.[1][6][lower-alpha 2] The government's decision to release him came shortly after the Afghan attack on Safavid Iran from within its far easternmost domains.[1][6][10] Soltan Hoseyn and the government were hoping that Daud Beg and his Daghestani allies would assist in countering the revolt on the eastern front, but Daud instead put himself at the head of a tribal coalition, and then launched a campaign against both the Safavid government forces and the empire's Shia population, eventually marching upon the provincial capital of Shamakhi.[1]

Shortly before the siege, the Sunnis of Shirvan province appealed for help from the Ottomans, their co-religionists[4] and the arch-rivals of the Safavids.[12] The rebel "coalition" consisting of some 15,000 tribesmen, headed by Daud Beg and assisted by Surkhay Khan of the Ghazikumukh, moved towards Shamakhi[lower-alpha 3] which was subsequently put under siege.[1][13] Eventually, the Sunni inhabitants of Shamakhi opened one of the gates of the city to the besiegers; Shamakhi was taken on 18 August 1721, upon which thousands of Shia residents were massacred,[lower-alpha 4] while Christians and foreigners were merely robbed.[1][4] Several Russian merchants were killed as well.[1][14] The stores of the many Russian merchants were looted, resulting in grave economic losses for them.[15][lower-alpha 5] Amongst the merchants was Matvei Evreinov, "reputedly the wealthiest merchant in Russia", who suffered huge losses.[1] The Shia Safavid governor of the city, his nephew, and the rest of his relatives were "cut to pieces by the mob, and their bodies thrown to the dogs".[4][17] After the province was completely overrun by the rebels, Daud Beg appealed to the Russians for protection, declaring his loyalty to the Tsar.[16] Upon being rebuffed, he appealed to the Ottomans, this time successfully; he was then designated by the Sultan as Ottoman governor of Shirvan.[18][1][16]

Aftermath

Artemy Volynsky reported to then Tsar Peter the Great (r. 1682–1725) on the considerable harm done to the Russian merchants and their livelihoods.[15][1] The report stipulated that the 1721 event was a clear violation of the 1717 Russo–Iranian trade treaty, by which the latter had guaranteed to ensure the protection of Russian nationals within the Safavid domains.[15] With the Safavid realm in chaos, and the Safavid ruler unable to fulfill the provisions of the treaty, Volynsky urged Peter to take advantage of the situation and to invade Iran on the pretext of restoring order as an ally of the Safavid king.[15][1] Indeed, Russia shortly afterward used the attack on its merchants in Shamakhi as a pretext to launch the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723.[19][20][10] The episode brought trade between Iran and Russia to a standstill, and made the city of Astrakhan the terminus for the Volga trade route.[10]

Notes

- "Nizovoi" was the Russian name for "Niazabad", an Iranian port 40 km to the northeast of Shamakhi on the Caspian littoral, to the south of Derbent.[8][9] Though it was "hardly" an ideal harbor according to Matthee, Niazabad was only one of few viable ports on the western littoral of the Caspian Sea.[8]

- Daud Beg is also referred to in the sources as "Daud Khan", "Davud Khan Lezgi", "Hajji Davud", "Hajji Da'ud", and "Hajji Da'ud Beg".[10][2][11]

- The rebel coalition reached Shamakhi on 15 August 1721.[13]

- Between 4,000–5,000 Shia's (which includes the city's officials) were killed.[14][7]

- According to Atkin, "perhaps half a million rubles' worth of their property was seized".[14] According to Rudi Mathee, the merchants "are said to have lost 70,000–100,000 tomans", citing Bachoud, Lettre de Chamakié, p. 99, for the 70,000 claim, and the Russian consul Avramov for the 100,000 claim.[10] He then later adds that the Russian sources speak of 400,000 tomans in lost merchandise, but that this is likely an exaggeration in an attempt to "bolster justification" for the Russian attack.[16] The more realistic reports according to Matthee are the ones that state 60,000 tomans.[16]

References

- Kazemzadeh 1991, p. 316.

- Mikaberidze 2011, p. 761.

- Matthee 2005, p. 27.

- Axworthy 2010, p. 42.

- Savory 2007, p. 251.

- Matthee 2012, p. 223.

- Matthee 2012, p. 225.

- Matthee 1999, p. 54.

- Lockhart 1958, p. 577.

- Matthee 1999, p. 223.

- Rashtiani 2018, p. 167.

- Rothman 2015, p. 236.

- Matthee 2015, pp. 489–490.

- Atkin 1980, p. 4.

- Sicker 2001, p. 48.

- Matthee 2012, p. 226.

- Matthee 2015, p. 490.

- Sicker 2001, pp. 47–48.

- Axworthy 2010, p. 62.

- Matthee 2005, p. 28.

Sources

- Atkin, Muriel (1980). Russia and Iran, 1780–1828. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5697-4.

- Axworthy, Michael (2010). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85772-193-8.

- Brunner, Rainer (2011). "MAJLESI, Moḥammad-Bāqer". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- Lockhart, Laurence (1958). The Fall of the Safavī Dynasty and the Afghan Occupation of Persia. Cambridge University Press.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. (1999). The Politics of Trade in Safavid Iran: Silk for Silver, 1600–1730. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-521-64131-9.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. (2005). The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500–1900. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11855-0.

- Matthee, Rudi (2012). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-745-0.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015). "Poverty and Perseverance: The Jesuit Mission of Isfahan and Shamakhi in Late Safavid Iran". Al-Qanṭara. 36 (2): 463–501. doi:10.3989/alqantara.2015.014.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander, ed. (2011). "Russo-Iranian Wars". Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1.

- Rashtiani, Goodarz (2018). "Iranian–Russian Relations in the Eighteenth Century". In Axworthy, Michael (ed.). Crisis, Collapse, Militarism and Civil War: The History and Historiography of 18th Century Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190250331.

- Rothman, E. Nathalie (2015). Brokering Empire: Trans-Imperial Subjects between Venice and Istanbul. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6312-9.

- Savory, Roger (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04251-2.

- Sicker, Martin (2001). The Islamic World in Decline: From the Treaty of Karlowitz to the Disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-96891-5.