Safety engineering

Safety engineering is an engineering discipline which assures that engineered systems provide acceptable levels of safety. It is strongly related to industrial engineering/systems engineering, and the subset system safety engineering. Safety engineering assures that a life-critical system behaves as needed, even when components fail.

Analysis techniques

Analysis techniques can be split into two categories: qualitative and quantitative methods. Both approaches share the goal of finding causal dependencies between a hazard on system level and failures of individual components. Qualitative approaches focus on the question "What must go wrong, such that a system hazard may occur?", while quantitative methods aim at providing estimations about probabilities, rates and/or severity of consequences.

The complexity of the technical systems such as Improvements of Design and Materials, Planned Inspections, Fool-proof design, and Backup Redundancy decreases risk and increases the cost. The risk can be decreased to ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) or ALAPA (as low as practically achievable) levels.

Traditionally, safety analysis techniques rely solely on skill and expertise of the safety engineer. In the last decade model-based approaches, like STPA (Systems Theoretic Process Analysis), have become prominent. In contrast to traditional methods, model-based techniques try to derive relationships between causes and consequences from some sort of model of the system.

Traditional methods for safety analysis

The two most common fault modeling techniques are called failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) and fault tree analysis (FTA). These techniques are just ways of finding problems and of making plans to cope with failures, as in probabilistic risk assessment. One of the earliest complete studies using this technique on a commercial nuclear plant was the WASH-1400 study, also known as the Reactor Safety Study or the Rasmussen Report.

Failure modes and effects analysis

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a bottom-up, inductive analytical method which may be performed at either the functional or piece-part level. For functional FMEA, failure modes are identified for each function in a system or equipment item, usually with the help of a functional block diagram. For piece-part FMEA, failure modes are identified for each piece-part component (such as a valve, connector, resistor, or diode). The effects of the failure mode are described, and assigned a probability based on the failure rate and failure mode ratio of the function or component. This quantization is difficult for software ---a bug exists or not, and the failure models used for hardware components do not apply. Temperature and age and manufacturing variability affect a resistor; they do not affect software.

Failure modes with identical effects can be combined and summarized in a Failure Mode Effects Summary. When combined with criticality analysis, FMEA is known as Failure Mode, Effects, and Criticality Analysis or FMECA, pronounced "fuh-MEE-kuh".

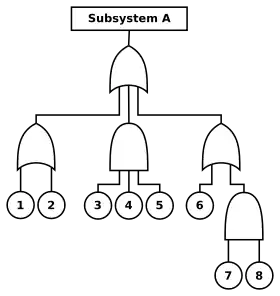

Fault tree analysis

Fault tree analysis (FTA) is a top-down, deductive analytical method. In FTA, initiating primary events such as component failures, human errors, and external events are traced through Boolean logic gates to an undesired top event such as an aircraft crash or nuclear reactor core melt. The intent is to identify ways to make top events less probable, and verify that safety goals have been achieved.

Fault trees are a logical inverse of success trees, and may be obtained by applying de Morgan's theorem to success trees (which are directly related to reliability block diagrams).

FTA may be qualitative or quantitative. When failure and event probabilities are unknown, qualitative fault trees may be analyzed for minimal cut sets. For example, if any minimal cut set contains a single base event, then the top event may be caused by a single failure. Quantitative FTA is used to compute top event probability, and usually requires computer software such as CAFTA from the Electric Power Research Institute or SAPHIRE from the Idaho National Laboratory.

Some industries use both fault trees and event trees. An event tree starts from an undesired initiator (loss of critical supply, component failure etc.) and follows possible further system events through to a series of final consequences. As each new event is considered, a new node on the tree is added with a split of probabilities of taking either branch. The probabilities of a range of "top events" arising from the initial event can then be seen.

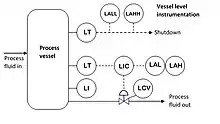

Oil and gas industry offshore (API 14C; ISO 10418)

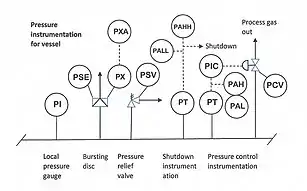

The offshore oil and gas industry uses a qualitative safety systems analysis technique to ensure the protection of offshore production systems and platforms. The analysis is used during the design phase to identify process engineering hazards together with risk mitigation measures. The methodology is described in the American Petroleum Institute Recommended Practice 14C Analysis, Design, Installation, and Testing of Basic Surface Safety Systems for Offshore Production Platforms.

The technique uses system analysis methods to determine the safety requirements to protect any individual process component, e.g. a vessel, pipeline, or pump.[1] The safety requirements of individual components are integrated into a complete platform safety system, including liquid containment and emergency support systems such as fire and gas detection.[1]

The first stage of the analysis identifies individual process components, these can include: flowlines, headers, pressure vessels, atmospheric vessels, fired heaters, exhaust heated components, pumps, compressors, pipelines and heat exchangers.[2] Each component is subject to a safety analysis to identify undesirable events (equipment failure, process upsets, etc.) for which protection must be provided.[3] The analysis also identifies a detectable condition (e.g. high pressure) which is used to initiate actions to prevent or minimize the effect of undesirable events. A Safety Analysis Table (SAT) for pressure vessels includes the following details.[3][4]

| Safety Analysis Table (SAT) pressure vessels | ||

|---|---|---|

| Undesirable event | Cause | Detectable abnormal condition |

| Overpressure | Blocked or restricted outlet

Inflow exceeds outflow Gas blowby (from upstream) Pressure control failure Thermal expansion Excess heat input |

High pressure |

| Liquid overflow | Inflow exceeds outflow

Liquid slug flow Blocked or restricted liquid outlet Level control failure |

High liquid level |

Other undesirable events for a pressure vessel are under-pressure, gas blowby, leak, and excess temperature together with their associated causes and detectable conditions.[4]

Once the events, causes and detectable conditions have been identified the next stage of the methodology uses a Safety Analysis Checklist (SAC) for each component.[5] This lists the safety devices that may be required or factors that negate the need for such a device. For example, for the case of liquid overflow from a vessel (as above) the SAC identifies:[6]

- A4.2d - High level sensor (LSH)[7]

- 1. LSH installed.

- 2. Equipment downstream of gas outlet is not a flare or vent system and can safely handle maximum liquid carry-over.

- 3. Vessel function does not require handling of separate fluid phases.

- 4. Vessel is a small trap from which liquids are manually drained.

The analysis ensures that two levels of protection are provided to mitigate each undesirable event. For example, for a pressure vessel subjected to over-pressure the primary protection would be a PSH (pressure switch high) to shut off inflow to the vessel, secondary protection would be provided by a pressure safety valve (PSV) on the vessel.[8]

The next stage of the analysis relates all the sensing devices, shutdown valves (ESVs), trip systems and emergency support systems in the form of a Safety Analysis Function Evaluation (SAFE) chart.[2][9]

| Safety Analysis Function Evaluation (SAFE) chart | Close inlet valve | Close outlet valve | Alarm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESV-1a | ESV-1b | |||||

| Identification | Service | Device | SAC reference | |||

| V-1 | HP separator | PSH | A4.2a1 | X | X | |

| LSH | A4.2d1 | X | X | |||

| LSL | A4.2e1 | X | X | |||

| PSV | A4.2c1 | |||||

| etc. | ||||||

| V-2 | LP separator | etc. | ||||

X denotes that the detection device on the left (e.g. PSH) initiates the shutdown or warning action on the top right (e.g. ESV closure).

The SAFE chart constitutes the basis of Cause and Effect Charts which relate the sensing devices to shutdown valves and plant trips which defines the functional architecture of the process shutdown system.

The methodology also specifies the systems testing that is necessary to ensure the functionality of the protection systems.[10]

API RP 14C was first published in June 1974.[11] The 8th edition was published in February 2017.[12] API RP 14C was adapted as ISO standard ISO 10418 in 1993 entitled Petroleum and natural gas industries — Offshore production installations — Analysis, design, installation and testing of basic surface process safety systems.[13] The latest 2003 edition of ISO 10418 is currently (2019) undergoing revision.

Safety certification

Typically, safety guidelines prescribe a set of steps, deliverable documents, and exit criterion focused around planning, analysis and design, implementation, verification and validation, configuration management, and quality assurance activities for the development of a safety-critical system.[14] In addition, they typically formulate expectations regarding the creation and use of traceability in the project. For example, depending upon the criticality level of a requirement, the US Federal Aviation Administration guideline DO-178B/C requires traceability from requirements to design, and from requirements to source code and executable object code for software components of a system. Thereby, higher quality traceability information can simplify the certification process and help to establish trust in the maturity of the applied development process.[15]

Usually a failure in safety-certified systems is acceptable if, on average, less than one life per 109 hours of continuous operation is lost to failure.{as per FAA document AC 25.1309-1A} Most Western nuclear reactors, medical equipment, and commercial aircraft are certified to this level. The cost versus loss of lives has been considered appropriate at this level (by FAA for aircraft systems under Federal Aviation Regulations).[16][17][18]

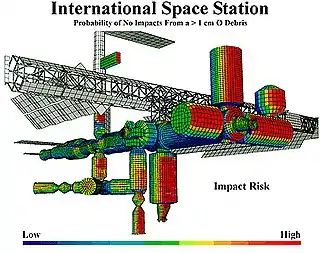

Preventing failure

Once a failure mode is identified, it can usually be mitigated by adding extra or redundant equipment to the system. For example, nuclear reactors contain dangerous radiation, and nuclear reactions can cause so much heat that no substance might contain them. Therefore, reactors have emergency core cooling systems to keep the temperature down, shielding to contain the radiation, and engineered barriers (usually several, nested, surmounted by a containment building) to prevent accidental leakage. Safety-critical systems are commonly required to permit no single event or component failure to result in a catastrophic failure mode.

Most biological organisms have a certain amount of redundancy: multiple organs, multiple limbs, etc.

For any given failure, a fail-over or redundancy can almost always be designed and incorporated into a system.

There are two categories of techniques to reduce the probability of failure: Fault avoidance techniques increase the reliability of individual items (increased design margin, de-rating, etc.). Fault tolerance techniques increase the reliability of the system as a whole (redundancies, barriers, etc.).[19]

Safety and reliability

Safety engineering and reliability engineering have much in common, but safety is not reliability. If a medical device fails, it should fail safely; other alternatives will be available to the surgeon. If the engine on a single-engine aircraft fails, there is no backup. Electrical power grids are designed for both safety and reliability; telephone systems are designed for reliability, which becomes a safety issue when emergency (e.g. US "911") calls are placed.

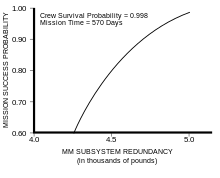

Probabilistic risk assessment has created a close relationship between safety and reliability. Component reliability, generally defined in terms of component failure rate, and external event probability are both used in quantitative safety assessment methods such as FTA. Related probabilistic methods are used to determine system Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF), system availability, or probability of mission success or failure. Reliability analysis has a broader scope than safety analysis, in that non-critical failures are considered. On the other hand, higher failure rates are considered acceptable for non-critical systems.

Safety generally cannot be achieved through component reliability alone. Catastrophic failure probabilities of 10−9 per hour correspond to the failure rates of very simple components such as resistors or capacitors. A complex system containing hundreds or thousands of components might be able to achieve a MTBF of 10,000 to 100,000 hours, meaning it would fail at 10−4 or 10−5 per hour. If a system failure is catastrophic, usually the only practical way to achieve 10−9 per hour failure rate is through redundancy.

When adding equipment is impractical (usually because of expense), then the least expensive form of design is often "inherently fail-safe". That is, change the system design so its failure modes are not catastrophic. Inherent fail-safes are common in medical equipment, traffic and railway signals, communications equipment, and safety equipment.

The typical approach is to arrange the system so that ordinary single failures cause the mechanism to shut down in a safe way (for nuclear power plants, this is termed a passively safe design, although more than ordinary failures are covered). Alternately, if the system contains a hazard source such as a battery or rotor, then it may be possible to remove the hazard from the system so that its failure modes cannot be catastrophic. The U.S. Department of Defense Standard Practice for System Safety (MIL–STD–882) places the highest priority on elimination of hazards through design selection.[20]

One of the most common fail-safe systems is the overflow tube in baths and kitchen sinks. If the valve sticks open, rather than causing an overflow and damage, the tank spills into an overflow. Another common example is that in an elevator the cable supporting the car keeps spring-loaded brakes open. If the cable breaks, the brakes grab rails, and the elevator cabin does not fall.

Some systems can never be made fail safe, as continuous availability is needed. For example, loss of engine thrust in flight is dangerous. Redundancy, fault tolerance, or recovery procedures are used for these situations (e.g. multiple independent controlled and fuel fed engines). This also makes the system less sensitive for the reliability prediction errors or quality induced uncertainty for the separate items. On the other hand, failure detection & correction and avoidance of common cause failures becomes here increasingly important to ensure system level reliability.[21]

See also

- ARP4761 – aerospace recommended practice

- Earthquake engineering – Study of earthquake-resistant structures

- Effective safety training

- Forensic engineering – Investigation of failures associated with legal intervention

- Hazard and operability study – Study of risks in a plan or operation

- IEC 61508 – International standard for safety-related systems

- Loss-control consultant

- Nuclear safety – Regulations for uses of radioactive materials

- Occupational medicine – Medical specialty concerned with the maintenance of health in the workplace

- Occupational safety and health – Field concerned with the safety, health and welfare of people at work

- Process safety – safety of facilities handling hazardous or flammable materials

- Reliability engineering – Sub-discipline of systems engineering that emphasizes dependability

- Risk assessment – Estimation of risk associated with exposure to a given set of hazards

- Risk management – Identification, evaluation and control of risks

- Safety life cycle – series of phases from initiation and specifications of safety requirements, covering design and development of safety features in a safety-critical system, and ending in decommissioning of that system

- Zonal safety analysis

Associations

- Institute of Industrial Engineers – Professional society for the support of the industrial engineering profession

- International System Safety Society

References

Notes

- API RP 14C p.1

- API RP 14C p.vi

- API RP 14C p.15-16

- API RP 14C p.28

- API RP 14C p.57

- API RP 14C p.29

- "Identification and reference designation".

- API RP 14C p.10

- API RP 14C p.80

- API RP 14C Appendix D

- Farrell, Tim (1978). "Impact of API 14C on the Design And Construction of Offshore Facilities". All Days. doi:10.2118/7147-MS. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "API RP 14C". Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "ISO 10418". Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Rempel, Patrick; Mäder, Patrick; Kuschke, Tobias; Cleland-Huang, Jane (2014-01-01). "Mind the gap: Assessing the conformance of software traceability to relevant guidelines". Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering. ICSE 2014. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 943–954. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.660.2292. doi:10.1145/2568225.2568290. ISBN 9781450327565. S2CID 12976464.

- Mäder, P.; Jones, P. L.; Zhang, Y.; Cleland-Huang, J. (2013-05-01). "Strategic Traceability for Safety-Critical Projects". IEEE Software. 30 (3): 58–66. doi:10.1109/MS.2013.60. ISSN 0740-7459. S2CID 16905456.

- ANM-110 (1988). System Design and Analysis (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Advisory Circular AC 25.1309-1A. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- S–18 (2010). Guidelines for Development of Civil Aircraft and Systems. Society of Automotive Engineers. ARP4754A.

- S–18 (1996). Guidelines and methods for conducting the safety assessment process on civil airborne systems and equipment. Society of Automotive Engineers. ARP4761.

- Tommaso Sgobba. "Commercial Space Safety Standards: Let’s Not Re-Invent the Wheel". 2015.

- Standard Practice for System Safety (PDF). E. U.S. Department of Defense. 1998. MIL-STD-882. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- Bornschlegl, Susanne (2012). Ready for SIL 4: Modular Computers for Safety-Critical Mobile Applications (pdf). MEN Mikro Elektronik. Retrieved 2015-09-21.

Sources

- Lees, Frank (2005). Loss Prevention in the Process Industries (3 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-7555-0.

- Kletz, Trevor (1984). Cheaper, safer plants, or wealth and safety at work: notes on inherently safer and simpler plants. I.Chem.E. ISBN 978-0-85295-167-5.

- Kletz, Trevor (2001). An Engineer's View of Human Error (3 ed.). I.Chem.E. ISBN 978-0-85295-430-0.

- Kletz, Trevor (1999). HAZOP and HAZAN (4 ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-85295-421-8.

- Lutz, Robyn R. (2000). Software Engineering for Safety: A Roadmap (PDF). The Future of Software Engineering. ACM Press. ISBN 978-1-58113-253-3. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- Grunske, Lars; Kaiser, Bernhard; Reussner, Ralf H. (2005). "Specification and Evaluation of Safety Properties in a Component-based Software Engineering Process". Springer: 737–738. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.69.7756.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - US DOD (10 February 2000). Standard Practice for System Safety (PDF). Washington, DC: US DOD. MIL-STD-882D. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- US FAA (30 December 2000). System Safety Handbook. Washington, DC: US FAA. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- NASA (16 December 2008). Agency Risk Management Procedural Requirements. NASA. NPR 8000.4A.

- Leveson, Nancy (2011). Engineering a Safer World - Systems Thinking Applied To Safety. Engineering Systems. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01662-9. Retrieved 3 July 2012.