Saharan Air Layer

The Saharan Air Layer (SAL) is an extremely hot, dry and sometimes dust-laden layer of the atmosphere that often overlies the cooler, more-humid surface air of the Atlantic Ocean. It carries upwards of 60 million tonnes of dust annually over the ocean and the Americas.[1] This annual phenomenon sometimes cools the ocean and suppresses Atlantic tropical cyclogenesis.[2]

The SAL is a subject of ongoing study and research. Its existence was first postulated in 1972.[3]: 1330

Creation

The dust cloud originates in Saharan Africa and extends from the surface upwards several kilometers. As the dust drives, or is driven out over the Atlantic ocean, it is lifted above the denser marine air. This atmospheric arrangement is an inversion where the temperature actually increases with height, as the boundary between the SAL and the marine layer suppresses or "caps" any convection originating in the marine layer. Since it is dry air, the lapse rate within the SAL itself is steep, that is, the temperature falls rapidly with height.[4]

Disturbances such as large thunderstorm complexes over North Africa periodically result in vast dust and sand storms, some of which extend as high as 6,000 metres (20,000 ft). The layer is transported westwards cross the Atlantic by a series of broad anticyclonic eddies that are typically found 1,500–4,500 metres (4,900–14,800 ft) above sea level.[5] An estimated 60-200 million tons of dust particles are carried from the Sahara Desert region of North Africa, where it originates, and moves westward annually.[1]

Sometimes a depression to the southwest of the Canary Islands increases the wind speed and intensity of the SAL, which can lift the dust around 5,000 metres (16,000 ft) into the air and often carries the dust as far as the Caribbean.[6]

Effects

.png.webp)

The SAL passes over the Canary Islands where the phenomenon is named "calima" (English: "haze") and manifests as a fog that reduces visibility and deposits a layer of dust over everything. It is especially prevalent in the winter months. Canary islanders suffer respiratory problems during this weather event, and sometimes the dust is so bad that public life and transport halt completely. On January 8, 2002, the dust was so heavy over the Tenerife South Airport, dropping the visibility to 50 metres (160 ft), that it was forced to close.[6]

From Northern Africa, winds blow twenty percent of dust from a Saharan storm out over the Atlantic Ocean, and twenty percent of that, or four percent of a single storm's dust, reaches all the way to the western Atlantic. The remainder settles out into the ocean or washes out of the air with rainfall. Scientists believe the July 2000 measurements made in Puerto Rico, nearly 8 million tonnes, equaled about one-fifth of the year's total dust deposits.

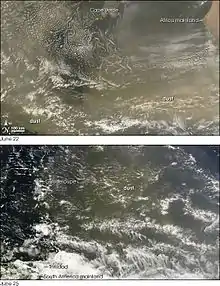

The clouds of dust SAL creates are visible in satellite photos as a milky white to gray shade, similar to haze.

Findings to date indicate that the iron-rich dust particles that often occur within the SAL reflect solar radiation, thus cooling the atmosphere. The particles also reduce the amount of sunlight reaching the ocean, thus reducing the amount of heating of the ocean.[2] They also tend to increase condensation as they drift into the marine layer below, but not precipitation as the drops formed are too small to fall and tend not to readily coalesce. These tiny drops are subsequently more easily evaporated as they move into drier air laterally or dry air mixes down from the SAL aloft.[7] Research on aerosols also shows that the presence of small particles in air tends to suppress winds. The SAL has also been observed to suppress the development and intensifying of tropical cyclones, which may be related directly to these factors.[8]

See also

References

- Prospero JM, Lamb PJ (7 November 2003). "African Droughts and Dust Transport to the Caribbean: Climate Change Implications". Science. 302 (5647): 1024–1027. Bibcode:2003Sci...302.1024P. doi:10.1126/science.1089915. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 14605365. S2CID 13426333.(subscription required)

- Lau KM, Kim KM (16 December 2007). "Cooling of the Atlantic by Saharan dust". Geophysical Research Letters. American Geophysical Union. 34 (23): n/a. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3423811L. doi:10.1029/2007GL031538.

- Prospero, Joseph M.; Mayol-Bracero, Olga L. (September 2013). "Understanding the Transport and Impact of African Dust on the Caribbean Basin". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Bureau of the American Meteorological Society. 94 (9): 1329–1337. Bibcode:2013BAMS...94.1329P. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00142.1.

- Wong S, Dessler AE (2005). "Suppression of deep convection over the tropical North Atlantic by the Saharan Air Layer". Geophysical Research Letters. American Geophysical Union. 32 (9). Bibcode:2005GeoRL..32.9808W. doi:10.1029/2004GL022295.

- Carlson, Toby N.; Prospero, Joseph M. (March 1972). "The Large-Scale Movement of Saharan Air Outbreaks over the Northern Equatorial Atlantic". Journal of Applied Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. 11 (2): 283–297. Bibcode:1972JApMe..11..283C. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1972)011<0283:TLSMOS>2.0.CO;2.

- "Calima". WeatherOnline. London: WeatherOnline Ltd. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Twohy, Cynthia H.; Kreidenweis, Sonia M.; Eidhammer, Trude; Browell, Edward V.; Heymsfield, Andrew J.; Bansemer, Aaron R.; Anderson, Bruce E.; Chen, Gao; Ismail, Syed; DeMott, Paul J.; Van Den Heever, Susan C. (13 January 2009). "Saharan dust particles nucleate droplets in eastern Atlantic clouds". Geophysical Research Letters. American Geophysical Union. 36 (1). Bibcode:2009GeoRL..36.1807T. doi:10.1029/2008GL035846.

- Jason P. Dunion; Christopher S. Velden (2004). "The impact of the Saharan Air Layer on Atlantic tropical cyclone activity". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. American Meteorological Society. 85 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1175/BAMS-85-3-353.