Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois

The Church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois is a Roman Catholic church in the First Arrondissement of Paris, situated at 2 Place du Louvre, directly across from the Louvre Palace. It was named for Germanus of Auxerre, the Bishop of Auxerre (378–448), who became a papal envoy and met Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, on his journeys. Genevieve is reputed to have converted queen Clotilde and her husband, French king Clovis I to Christianity at the tomb of Saint Germain in Auxerre.[1]

| Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 2 Place du Louvre, 1e |

| State | France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°51′34″N 2°20′26″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | French Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 12th century |

| Completed | 15th century |

| Direction of façade | West |

| Website | |

| www | |

The current church was built in the 13th century, with major modifications in the 15th and 16th centuries. From 1608 until 1806, it was the parish church for inhabitants of the palace, and many notable artists and architects who worked on the palace have their tombs in the church. Since the 2019 fire, which badly damaged Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral, the cathedral's regular services have been held at Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois.

History

The first place of worship on the site was a small oratory founded in the 5th century to commemorate a meeting of Saint Germain l'Auxerrois with Saint Genevieve, the future patron saint of Paris.[2] This structure was replaced by a large church, either by Chilperic I, King of Franks, in about 560, or by Saint Landry of Paris, the bishop of Paris, in about 650. That church was destroyed by the Normans in 886, rebuilt by King Robert II the Pious, and then underwent further construction in the 12th century. The church was, from the Middle Ages, both collegiate and parochial: that is to say that it was partly the seat of a college of canons, and the parish church for all the residents of the district.[3] By the 13th century, it was again considered too small, and was enlarged further.Further changes and additions were made in the 15th and 16th centuries. The current structure is largely from the 15th century,[1]

During the Wars of Religion, its bell, "Marie", was rung on the night of 23 August 1572, to signal the beginning of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. Thousands of Huguenots, who were visiting Paris for a royal wedding, were killed by the city's mob. The church hosted the funeral of François de Malherbe in 1628; and in 1720, that of sculptor Antoine Coysevox.

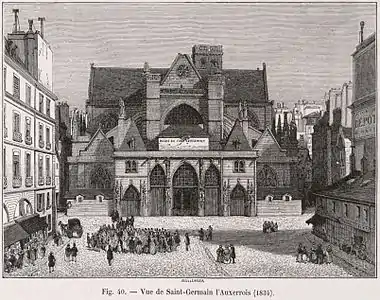

During the French Revolution, the church was closed, pillaged, and converted into a barn for storing feed for animals. a printing shop. and, for a time, as a gunpowder factory.[3] Some of the original stained glass still remains, despite the revolutionary vandalism. The building was returned to the church in 1801, but suffered again during an anticlerical riot in 1831, when many paintings, funeral monuments and windows were damaged or destroyed.[1] It was closed for several years, then underwent restoration between 1838 and 1855 under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Victor Baltard, who also removed some of the surrounding buildings and made the building more visible. It underwent major restoration between 1838 and 1855 before it could reopen.[1] Alexandre Boëly was organist at the church from 1840 to 1851.

The church was nearly demolished twice; once under Louis XIV, who envisaged enlarging the Louvre palace and building a new facade in its place; and again under Napoleon III; Baron Haussmann had a plan to install the beginning of a new boulevard on the site of the church, but the plan was put side after the construction of a small portion.

After 1 September 2019, following the serious fire at Notre-Dame, the cathedral's services were temporarily transferred to Saint-Germain.[4]

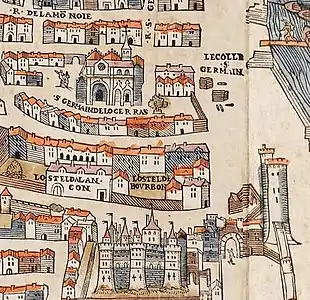

The church (top) on a 1550 map of Paris

The church (top) on a 1550 map of Paris The church in 1834, pre-Haussmann, almost hidden by other buildings

The church in 1834, pre-Haussmann, almost hidden by other buildings Church photographed in the 1850s, before rebuilding of belfry

Church photographed in the 1850s, before rebuilding of belfry Church painted by Claude Monet in 1867

Church painted by Claude Monet in 1867

Exterior

The west front

The west front View from the southeast, with bell tower in center

View from the southeast, with bell tower in center The Gothic porch, or fore-hall, unique in Paris (1435)

The Gothic porch, or fore-hall, unique in Paris (1435)

The exterior of the church harmoniously blends elements of Romanesque architecture, Rayonnant Gothic, Flamboyant Gothic, and Renaissance architecture. The only existing Romanesque elements, dating from the 12th century, are found in the lower portion of the bell tower, where it is attached to the south transept. The western portal was built around 1220-1230.[5] It was originally the meeting place of the Canons of the cathedral, who held their ecclesiastical court there, and was the classroom where pupils were instructed in the catechism.[6]

Above the rose window is a balustrade which encircles the whole church, a work of Jean Gaussel (1435–39).[7]

The statues on the west front, added in the 19th century, represent French saints, including kings and queens, and those important in the development of Christianity in Paris, including Germain d'Auxerre and Saint Clotilde. They are surrounded by a rich assortment of sculpted animals, beggars and fools.

The arches over the doorway are also crowded with sculpture dating to the end of the 14th century, depicting apostles, angels, the damned and the chosen, sages, and foolish and wise virgins. On the piers of the windows and arches are six reposing statues, resting atop demons and other figures, representing King Childebert I, his wife Queen Ultrogotha, and Saint Genevieve, carrying a torch representing the light of Christ. Next to her, an angel relights a torch which a devil has just extinguished. The keys of the vaults also are filled with biblical personages, illustrating the Last Supper and the Adoration of Christ.[6]

The lateral facade is also richly adorned with sculpture, including pinnacles and gargoyles, which also had the practical function of projecting rainwater away from the sides of the building. The consoles of the pinnacles also contain sculpted heads of animals, grimacing monsters, griffons and other fantastic creatures.[6]

One sculptural decoration is a clever pun; it depicts several slices, or "troncons", of fish; they honor a merchant named Tronson who was a major donor to the construction of the church.

It now has construction in Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles. The most striking exterior feature is the porch, with a rose window

Statues on the north portal; kings of France

Statues on the north portal; kings of France Archivolte of West Front

Archivolte of West Front Detail of porch sculpture; devils and monsters

Detail of porch sculpture; devils and monsters Vault key sculpture – the Last Supper

Vault key sculpture – the Last Supper.jpg.webp) Sculpture of slices of carp on the exterior, a pun on the name of the donor

Sculpture of slices of carp on the exterior, a pun on the name of the donor

Bell towers

The original bell tower was placed against the south transept of the church in the late 12th century; its lower portions are the only remaining Romanesque elements of the church. This was the bell tower that gave the signal for the beginning of the Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre of Protestants on 23 August 1572.[1]

The north tower was added in about 1860 and is opposite the hall of the 1st arrondissement (1859). It was built by architect Theodore Ballu. It was part of the vast reconstruction of central Paris conducted by Baron Haussmann To maintain harmony, he made the facade of the city hall almost identical in size and form with the facade of the church, complete with a rose window and a porch. He also designed the campanile or bell tower between the church and the city hall, in the same Neo-Gothic style.[8] At the same time Ballu rebuilt the upper portions of the old belfry of the church.[3]

Rebuilt original bell tower of the church by Théodore Ballu, lower portion from the 12th century

Rebuilt original bell tower of the church by Théodore Ballu, lower portion from the 12th century The church bell tower (foreground), with the Louvre in background and the campanile of the arrondissement city hall behind and to right.

The church bell tower (foreground), with the Louvre in background and the campanile of the arrondissement city hall behind and to right. Campanile of the city hall of the 1st arrondissement by Théodore Ballu, linked to the church (right) and the city hall (left) (1858–63)

Campanile of the city hall of the 1st arrondissement by Théodore Ballu, linked to the church (right) and the city hall (left) (1858–63)

Interior

Nave

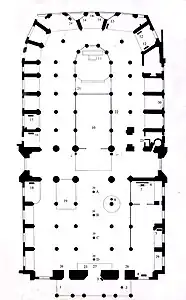

Plan of the church

Plan of the church Nave of the church, facing east, with pulpit (17th c.) on the right

Nave of the church, facing east, with pulpit (17th c.) on the right Bank of seats for the royal family (17th c.)

Bank of seats for the royal family (17th c.) Carving on the pulpit (17th c.)

Carving on the pulpit (17th c.).jpg.webp) A sculpted angel in the nave

A sculpted angel in the nave

The church has a standard plan: a long central nave, built in the 15th century,[5] on the west for the parishioners; a short transept, or crossing: the choir, where the clergy worshipped during the service; the altar, and the apse, with a ring of chapels, on the east. It is crossed by a short transept between the choir and the nave. There are collateral aisles between the nave outer walls, and the church is ringed by small chapels, each decorated with paintings and sculpture. Much of the decor comes from the time of Louis XIV, and the interior is lighter and brighter than in Gothic churches. The additional light is contributed by the upper windows, which, under the influence of the Neo-classical style, have a majority of clear rather than coloured glass.[6]

The most prominent element of the nave is the monumental carved wooden bank of seats created in 1684 for Louis XIV and the royal family. It is nearly in the center of the church, facing the pulpit. It was made by François Mercier, based on designs by Charles Le Brun.

The transept

The south transept, with 16th century rose window

The south transept, with 16th century rose window The north transept. The original rose window glass was destroyed in a workshop fire in 2009, and was replaced by clear glass.

The north transept. The original rose window glass was destroyed in a workshop fire in 2009, and was replaced by clear glass. North transept window; St. Vincent, martyr

North transept window; St. Vincent, martyr North transept- polychrome wood statue of saint Germain l'Auxerrois (15th c.)

North transept- polychrome wood statue of saint Germain l'Auxerrois (15th c.)

The south transept contains stained glass windows from both the 16th and 19th century.

The north transept retained most of its original 16th-century stained glass, as well as 19th century windows. but a fire 2009 in the workshop where the windows were being restored destroyed them, and they were replaced by clear glass. The north transept also displays a polychrome wood statue of Saint Germain l'Auxerrois, dating to the 15th century.[9]

The choir and altar

The choir, longer than the nave

The choir, longer than the nave.jpg.webp) Lancet windows of the choir (19th c.)

Lancet windows of the choir (19th c.) The altar in the choir. The columns in the choir have cannelures, or vertical grooves, typical of classical or Renaissance architecture

The altar in the choir. The columns in the choir have cannelures, or vertical grooves, typical of classical or Renaissance architecture

The choir, where the clergy traditionally workshops, is unusual because it is longer than the nave, the seating for lay parishioners. Its Gothic architecture makes it the oldest part of the church interior, though it is overlaid with a considerable amount of Renaissance decoration, particularly the cannelures or vertical grooves of the columns, typical of the classical style.

The Chapel of the Virgin

The Chapel of the Virgin (13h c.) (left)

The Chapel of the Virgin (13h c.) (left) Detail of the "Crowning of the Virgin" in the Chapel of the Virgin

Detail of the "Crowning of the Virgin" in the Chapel of the Virgin Statue of Saint Germain the Auxerrois (13th c.)

Statue of Saint Germain the Auxerrois (13th c.) Statue of Saint Marie the Egyptian (end 15th or beginning of 16th century), with her three loaves of bread

Statue of Saint Marie the Egyptian (end 15th or beginning of 16th century), with her three loaves of bread

The Chapel of the Virgin, usually located in the east end of a cathedral, is found at Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois near the entrance of the church on the south collateral aisle. The choir and the first bay of the chapel date from the 14th century.[5] It was created by combining four earlier chapels, then restored in the 19th century. It was originally used exclusively by the cannons of the cathedral chapter, but in the 15th century the cannons moved to the choir and the chapel was opened to the entire congregation.[1]

The chapel is decorated with very elaborate sculpture combined with a with a group of paintings by the 19th century artist Eugene Amaury-Duval (1808–1185), especially the fresco painting "The Crowning of the Virgin". His works were created in a style close to that of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in the 14th century, especially the work of Fra Angelico, with a great simplicity of composition and elegance. Amaury-Duval's His paintings are distinguished from the Pre-Raphaelites by their more sculptural figures.[1]

The oldest work on display in the chapel is a statue of the patron saint of the church, Saint Germain of Auxerre, dating from 13rh century. Nearby is a statue of Saint Mary the Egyptian, from the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century. The figure depicts her clothed only with her long hair, and holding three loaves of bread, which, according to her legend, allowed her to live for sixty years in the Egyptian desert.[6]

The Chapel of the Tomb

The Chapel of the Tomb

The Chapel of the Tomb Sepulchre of Christ altar in the Chapel of the Tomb (1840)

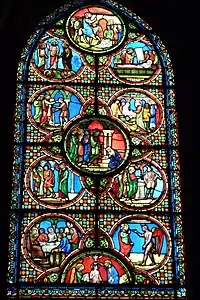

Sepulchre of Christ altar in the Chapel of the Tomb (1840) Chapel window with scenes of life of Christ, by Etienne Thevenot (1840)

Chapel window with scenes of life of Christ, by Etienne Thevenot (1840)

The Chapel of the Tomb (or Chapel of Calvary), along the disambulatory behind the altar at the east end of the church, is one of the oldest in the church. It was created in 1505 by a merchant of drapery named Tronson. He also donated money for ornament of the exterior, sculpture slices of fish, or "Trocons", a pun on his name. It became the chapel of the Guild of Drapers, which held special masses and events in the chapel. During the 1831 riots, the chapel was badly damaged, the tombs pillaged and the stained glass smashed. It was restored in the Neo-Gotnic style beginning in 1840, with new stained glass by Etienne Thevenot (1840), modelled after the windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with scenes depicting the life of Christ. The altar dates to the 1840, and is in the Louis XIV style, carved of the stone of Conflans. The origin of the statue of Christ below the altar in the chapel is of uncertain origin, likely from the 16th century.[10]

The Disambulatory

The Disambulatory, looking southwest. To the left is the Chapel of Saint Landry

The Disambulatory, looking southwest. To the left is the Chapel of Saint Landry

The disambulatory is the passageway that circles the church, enabling parishioners to walk around to the chapels even when a service is going on. It leads to several important chapels and displays several important works of decorative art.

At the entrance to the sacristy is a major work of the 17th century painter Sebastien Bourdon (1616–1671), "Saint Pierre Nolasque receives the habit of the Order of Notre Dame of Mercy." It is an example of the enormous and complex altar paintings for which he was known. Painted at the height of hs career, it displays his particular skill at blending architecture and crowds of figures in rising levels.[11]

Another notable work in the disambulatory is the triptych depicting the history of the original sin and the Legend of the Virgin Mary. It was made of carved and painted wood in Flanders between 1510 and 1530. It portrays (right) God the Father offering the fruits of the tree of life to Adam and Eve; (left) Satan extends the forbidden fruit to Eve; and (center), scenes form the life of the Virgin Mary. It was confiscated from the Church during the Revolution and returned afterwards, with two panels missing.[11]

The Chapel of the Patron Saints

Chapel of the Patron Saints

Chapel of the Patron Saints Neogothic retable in the Chapel of the Patron Saints

Neogothic retable in the Chapel of the Patron Saints Rostaing tombs in the Chapel of the Patron Saints

Rostaing tombs in the Chapel of the Patron Saints

The Chapel of the Patron Saints, accessed from the ambulatory around the choir, traditionally contained the tombs of those who were authorised burial in the church, but did not have a separate sepulchre. When the chapel was restored, many tombs were found. The two statues are from the Rostaing family.

The Chapel of Saint Landry of Paris

Tomb of Saint Landry of Paris, founder the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris hospital

Tomb of Saint Landry of Paris, founder the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris hospital

The Chapel of Saint Landry dates from the 19th century, but it was originally built between 1521 and 1522, and was originally devoted to Saint Peter and Sent Paul. It became a family tomb for Etienne d'Alegre in 1624. It 1817, Louis XVIII took it as the repository of the heart of Joseph Hyacinthe François-de-Paule de Rigaud, comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817). The rest of Rigaud's corpse remained in the family plot of the Calvaire cemetery in Paris. Later in the 19th century, after the overthrow of Louis XVIII, it was rededicated to Saint Landry of Paris, who died in 661. Landry was the Bishop of Paris in the 7th century who founded the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, the oldest Paris hospital, considered the oldest hospital in the world still in operation.[12]

The Chapel of Notre Dame, or of Compassion

.jpg.webp) The Flemish retable (16th c.)

The Flemish retable (16th c.) Detail of the Triptych of the Virgin Mary

Detail of the Triptych of the Virgin Mary.jpg.webp) Detail of the Triptych of the Virgin Mary

Detail of the Triptych of the Virgin Mary

The Chapel of the Compassion, accessed from the disambulatory, was the former royal chapel, and it contains one of the most notable works of art in the church, a Flemish carved retable made in about 1515 in Antwerp, near the end of the Middle Ages, when Flanders was at its artistic height. The carved sculpture represents scenes from the Old and New Testament, full of figures from all ranks of society, from kings and nobles to soldiers and peasants in traditional Flemish costume. The central compartment depicts a Tree of Jesse, illustrating the genealogy of Christ.[11]

Art and decoration

Early stained glass (16th century)

Detail of the Pentecost window (16th c.), south transept

Detail of the Pentecost window (16th c.), south transept "Incredulity of Saint Thomas" by Jean Chastellain (glass) and Noël Bellemare (drawing), (1533) south transept

"Incredulity of Saint Thomas" by Jean Chastellain (glass) and Noël Bellemare (drawing), (1533) south transept Detail of the "Incredulity of Saint Thomas" (1533), south transept

Detail of the "Incredulity of Saint Thomas" (1533), south transept

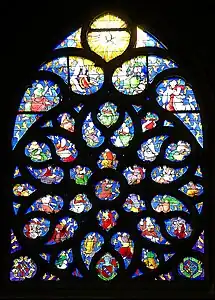

Most of the medieval and Renaissance stained glass was destroyed in the sacking of the church in 1831, but some notable examples remain. These include the rose window in the south transept, with scenes of the Pentecost designed by Jean Chastellan, with the Holy Spirit taking the form of a dove,[13] and the window depicting the Incredulity of saint Thomas, with glass by Jean Chastellain from a drawing by Noël Bellemare (1533).

Stained glass – 19th century

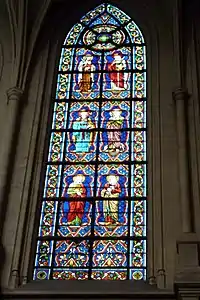

Window in Chapel of Virgin by Charles-Laurent Maréchal and Louis-Napoléon Gugnon (between 1844 and 1847)

Window in Chapel of Virgin by Charles-Laurent Maréchal and Louis-Napoléon Gugnon (between 1844 and 1847) Signature of Maréchal and Gugnon (1847)

Signature of Maréchal and Gugnon (1847) Scenes of the life of Christ, window by Etienne Thenvenot (1844–47)

Scenes of the life of Christ, window by Etienne Thenvenot (1844–47) Window of Saint Toby by Etienne Thenvenot (1844–47)

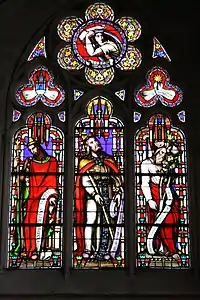

Window of Saint Toby by Etienne Thenvenot (1844–47) Window of Christ and the 12 Apostles, designed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, made by Antoine Lusson

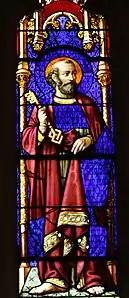

Window of Christ and the 12 Apostles, designed by Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, made by Antoine Lusson Saint Peter by Antoine Lusson

Saint Peter by Antoine Lusson Window depicting Saints Catherine, Theresa, Katherina of Alexandria, Chlotilde, Gertrude, Anna and Magdalena, by Antoine Lusson (1868)

Window depicting Saints Catherine, Theresa, Katherina of Alexandria, Chlotilde, Gertrude, Anna and Magdalena, by Antoine Lusson (1868)

Most of the medieval and Renaissance stained glass was destroyed during the Revolution and in the 1831 riots. but a few notable examples can still be found in the side chapels.

The largest part of the glass in the church dates to the mid-19th century. Very good examples of work of this period, by Charles-Laurent Maréchal and Louis-Napoléon Gugnon, made c. 1844, are found in the Chapel of the Virgin. Another major glass artist of the period, Etienne Thenvenot, created a multi-scene window of scenes of the life of the Virgin Mary, now in the Chapel of the Virgin.[14]

The rose window depicting "The Pentecost" in the south transept was made by Jean Chastellain.[15]

Antoine Lusson, who worked in collaboration with Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, also created Neo-Gothic glass for the church.

Organ

The organ on the tribune over the west entrance (18th c.)

The organ on the tribune over the west entrance (18th c.) The organ of the tribune

The organ of the tribune The choir organ (1838)

The choir organ (1838)

Nothing remains of the original organ of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois, built before the Revolution. Some accounts say that the present organ was transferred from Sainte Chapelle in July 1791. where it had been built twenty years earlier by François-Henri Clicquot, with a case designed by Pierre-Noël Rousset in 1752, but its neo-classical style seems to some writers to be too modern for that date.

In 1838, Following the destruction in the church interior in the 1835 riot, the organ underwent a major restoration by Louis-Paul Dallery, which continued until August 1841. Among the other modifications made by Dallery, at the request of the new organist, Alexandre Boëly (1785–1858), was the addition of additional keys and pedals to enable the organist to fully play the works of Johann-Sebastian Bach. The instrument underwent further major modifications between 1847 and 1850, 1864, and in 1970–1980. The last modification were made with the intent of recapturing the original sound of the first organ by Cliquot in the 18th century. This was not a success, and some parts of the instrument gradually became unplayable.

A new restoration was undertaken beginning in 2008, which undertook to clean out the dust, and to preserve as much as possible of the original mnechanism. Some of the old pipes and effects of the Cliquot organ which had become unplayable were cleaned and returned to service, and other pipes modified and reharmonized, to recapture, as much as possible the original sound.

The smaller choir organ, in the center of the church, was built in 1838 by John Abbey, enlarged in 1900 by Joseph Merklin, and reharmonmized in 1980 par Adrien Maciet.

The current organist is Michael Matthes, named in January 2019.

Latin mass

A Tridentine Mass, also called the traditional latin mass, is celebrated daily in the church. A sung mass on Sunday evenings is also celebrated, making it one of the few churches in Paris that still celebrates the Tridentine Mass.[16]

Notable tombs

The church contains a number of tombs of prominent artists who contributed to the decoration of the neighbouring Louvre during the 17th and 18th century. They include François de Malherbe (1628), Antoine Coysevox (1720), François Boucher (1770), and Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (1779).

See also

References

- Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 24

- MacErlean, Andrew. "St. Genevieve." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Art and Culture -Historique". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- "Home page". Notre-Dame de Paris. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois", Paris Tourist Office

- Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 25

- Presses Universitaires de France (1864). Revue Archéologique (in French). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. p. 595. OCLC 220839783.

- Curl, James Stevens (1999). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Art and Culture -Historique". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Art and Culture -Historique". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 26

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Art and Culture -Historique". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- Mairie de Paris: Vitraux parisiens. Les balades du patromoine Nr.11. Paris

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Art and Culture -Historique". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- (Mairie de Paris: Vitraux parisiens. Les balades du patromoine Nr.11. Paris 2010)

- "Église Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois de Paris » Tous nos horaires". saintgermainlauxerrois.fr. Retrieved 2018-07-21.

Further reading

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1

External links

- Website of the church (in French)

Media related to Église Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois de Paris at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Église Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois de Paris at Wikimedia Commons