Saint Brendan's Island

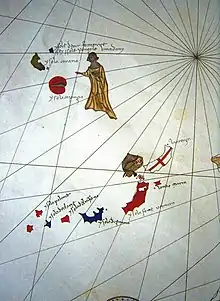

Saint Brendan's Island, also known as Saint Brendan's Isle, is a phantom island or mythical island, supposedly situated in the North Atlantic somewhere west of Northern Africa. It is named after Saint Brendan of Clonfert. He and his followers are said to have discovered it while travelling across the ocean and evangelising its islands. It appeared on numerous maps in Christopher Columbus's time, most notably Martin Behaim's Erdapfel of 1492. It is known as La isla de San Borondón and isla de Samborombón in Spanish.[1]

The first mention of the island was in the Latin text Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis ("Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot") of the ninth century, which inserted the island into Irish and European folklore.

History

Middle Ages

This island is named after Saint Brendan, who claimed to have landed on it in AD 512 with 14 monks, with whom he celebrated a Mass. The monastic party reported its stay as 15 days, while the ships that expected their return complained that they had to wait a year, during which period the island remained concealed behind a thick curtain of mist.

In his Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis, the monk Barino mentioned having visited this same "Paradise" in the Atlantic, it being a thickly wooded, mountainous island where the sun never set and it was always day, where the flora were abundant, the trees bore rich fruit, the rivers ran with fresh water, and the birds sang sweetly in the trees.

In Planiferio de Ebstorf of 1234, Marcos Martinez referred to "the lost island discovered by St Brendan[,] but nobody has found it since", and in Mapamundi de Hereford of 1275 the whole archipelago is described as "The Isles of the Blessed and the Island of St Brendan".

Early Modern Age

The Portuguese writer Luís Perdigão recorded the interest of the King of Portugal after a sea captain informed Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) that he had found the island but was driven off by tumultuous sea conditions. Henry ordered him back: he sailed off but never returned. Christopher Columbus is said to have believed in its existence.

In 1520, members of Ferdinand Magellan's expedition are thought to have named Samborombón Bay on the coast of Argentina after Saint Brendan's Isle, attributing the bay's nearly semicircular shape to the detachment of the wandering island from the South American mainland.[2]

In 1566, Hernán Pérez de Grado, First Regent of the Royal Canary Islands Court, ordered the justices at La Palma, El Hierro and La Gomera to investigate the phenomenon. In his history, Abreu y Galindo reports a conversation with a French adventurer claiming to have visited San Borondon, departing thence when a storm set in and making the voyage to La Palma for shelter within a day. In another report, Alonso de Espinosa, governor of El Hierro, described sighting San Borondon island northwest of El Hierro and "leeward" of La Palma. He listed 100 witnesses to the apparition.

Juan de Abréu Galindo reported in Historia de la Conquista de las siete Islas Canarias that "the island of Saint Brendan (San Borondon), which is the eighth and last, whose existence may be inferred from sightings of its apparitions, seems to be located at 20 degrees 30 minutes of latitude and eight leagues [40 kilometres] due west of La Gomera." (The longitude given in the coordinates is based on the old measurement before the introduction of the Greenwich meridian).

Modern Age

In 1719, the Scottish monk Sigbert de Gembloux reported seeing the island, as did Don Matea Dacesta, mayor of Valverde, El Hierro in 1721. As a result of these sightings, that same year Juan de Mur y Aguerre, military governor of the Canary Islands, appointed a new commission of inquiry under Gaspar Dominguez, a sea captain; no fresh evidence was uncovered and subsequently interest waned. According to the Canary historian Ramirez, in 1723 a priest performed the rite of exorcism towards the island during one of its apparitions behind a low cloud. This was witnessed by a large number of persons and sworn to on affidavit.

In 1759, a Franciscan friar mentioned (but not identified by name) by Viera y Clavijo wrote to a friend: "I was most desirous to see the island of San Borondon and, finding myself in Alexero, La Palma, on 3 May at six of the morning, I saw, and can swear to it on oath, that while having in plain view at the same time the island of El Hierro, I saw another island of the same colour and appearance, and I made out through a telescope, much-wooded terrain in its central area. Then I sent for the priest Antonio Jose Manrique, who had seen it twice previously, and upon arrival he saw only a portion of it, for when he was watching, a cloud obscured the mountain. It was subsequently visible for another 90 minutes. being seen by about forty spectators, but in the afternoon when we returned to the same point we could see nothing on account of the heavy rain."

In his Noticias, Vol I, 1772, chronicler Viera y Clavijo wrote: "A few years ago while returning from the Americas, the captain of a ship of the Canary Fleet believed he saw La Palma appear and, having set his course for Tenerife based on his sighting, was astonished to find the real La Palma materialize in the distance next morning." Viera adds that a similar entry is made in the diaries of Colonel don Roberto de Rivas, who made the observation that his ship "having been close to the island of La Palma in the afternoon, and not arriving there until late the next day", the officer was forced to conclude that "the wind and current must have been extraordinarily unfavourable during the night."

Further expeditions were organised in the search for the island, but from the 19th century onwards, reported sightings of San Borondon became less frequent.

See also

Notes

- Haase, Wolfgang; Reinhold, Meyer (1993). The Classical Tradition and the Americas: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition v. 1. Walter de Gruyter. p. 200. ISBN 978-3-11-011572-7.

- Sánchez Zinny, Fernando (21 July 2012). "Una leyenda anclada en la bahía de Samborombón". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 May 2017.