St. Martinville, Louisiana

St. Martinville (French: Saint-Martin)[2] is a city in and the parish seat of St. Martin Parish, Louisiana, United States.[3] It lies on Bayou Teche, 13 miles (21 km) south of Breaux Bridge,[4] 16 miles (26 km) southeast of Lafayette,[5] and 9 miles (14 km) north of New Iberia.[6] The population was 6,114 at the 2010 U.S. census, and 5,379 at the 2020 United States census.[7] It is part of the Lafayette metropolitan statistical area.

Saint Martinville, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City of Saint Martinville | |

Main Street | |

| Nickname: Petit Paris (Little Paris) | |

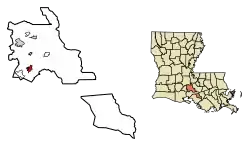

Location within St. Martin Parish, Louisiana | |

| Coordinates: 30°07′30″N 91°49′50″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Parish | St. Martin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jason Willis (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.16 sq mi (8.18 km2) |

| • Land | 3.05 sq mi (7.90 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.28 km2) |

| Elevation | 23 ft (7 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 5,379 |

| • Density | 1,762.45/sq mi (680.56/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 70582 |

| Area code | 337 |

| FIPS code | 22-67600 |

| Website | http://www.stmartinville.org/ |

History

In the 16th century, the area between the Atchafalaya River, in Louisiana, the Gulf of Mexico and Trinity River, in Texas, was occupied by numerous tribes or subdivisions of the Attakapan people. The territory was not closed to outsiders, and several traders roamed through it on business.

Europeans did not begin to settle there until French explorers claimed and founded the colony of Louisiana in 1699.[8] They referred to the territory between the Atchafalaya River and Bayou Nezpique, where the Eastern Atakapa lived, as the Attakapas Territory, adopting the name from the Choctaw language term for this people. The French colonial government gave land away to French soldiers and settlers.

Poste des Atakapas (Attakapas Post) was founded as a trading post on the banks of the Bayou Teche, and settlers started to arrive. Some came separately from France, such as M. Masse, who came about 1754 from Grenoble. Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire, a Frenchman from Lyon, and some other Frenchmen from Mobile, in present-day Alabama, arrived in late 1763 or early 1764. Fuselier bought land between Vermilion River and Bayou Teche from the Eastern Attakapas chief Kinemo. Shortly after that, the rival Appalousa (Opelousas) invaded the area via the Atchafalaya and Sabine rivers, and exterminated much of the Eastern Atakapan. Gabriel Fuselier's son Agricole Fuselier was prominent in settling what developed as New Iberia, Louisiana.

Gradually groups of more French speakers arrived, such as the first Acadians from Nova Scotia. They were assigned to this area in 1765 by Jean-Jacques Blaise d'Abbadie, the French official who was administering Louisiana for the Spanish. They had been expelled from Acadia by the British,[9][10] who had defeated France in the Seven Years' War and taken over its territories in North America east of the Mississippi River. Spain took over Louisiana and other territories west of the Mississippi but tended to rely on French colonists to administer La Louisiane.

The Acadians were led by Joseph Broussard. In 1768-1769, fifteen families arrived from Pointe Coupee, another French colonial community. Their members had migrated from Saint-Domingue (now Haïti) or from Paris via Fort de Chartres, in present-day Illinois. Between the arrivals of the two groups, the French captain Étienne de Vaugine came in 1764 and acquired a large domain east of Bayou Teche.

On April 25, 1766, after the arrival of the first Acadians, the census showed a population of 409 inhabitants for the Attakapas region. In 1767, the Attakapas Post had 150 inhabitants before the arrival of the 15 families from Pointe Coupee.

In 1803, after losing his effort to regain control over Saint-Domingue during its slave revolt, Napoleon sold Louisiana in 1803 to the United States through the Louisiana Purchase.[11] The U.S. settlers and territorial government organized the Attakapas Territory between 1807 and 1868. After Louisiana became a state, Saint Martin Parish was created. Attakapas Post was renamed as Saint Martinville and designated as the parish seat.

In 1867, Governor Benjamin Flanders appointed Monroe Baker as mayor who was one of the earliest if not the first African-American mayor to serve in the United States.[12]

Geography

St. Martinville is located at 30°7′30″N 91°49′50″W (30.125053, -91.830593), in Acadiana.[13] The city is part of the Lafayette metropolitan statistical area. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.0 square miles (7.8 km2), of which 3.0 square miles (7.8 km2) is land and 0.33% is water. Its terrain is mixture of swamp and prairie.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 652 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,190 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,606 | 35.0% | |

| 1890 | 1,814 | 13.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,926 | 6.2% | |

| 1910 | 2,318 | 20.4% | |

| 1920 | 2,465 | 6.3% | |

| 1930 | 2,455 | −0.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,501 | 42.6% | |

| 1950 | 4,614 | 31.8% | |

| 1960 | 6,468 | 40.2% | |

| 1970 | 7,153 | 10.6% | |

| 1980 | 7,965 | 11.4% | |

| 1990 | 7,137 | −10.4% | |

| 2000 | 6,989 | −2.1% | |

| 2010 | 6,114 | −12.5% | |

| 2020 | 5,379 | −12.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1,853 | 34.45% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 3,240 | 60.23% |

| Native American | 14 | 0.26% |

| Asian | 19 | 0.35% |

| Other/Mixed | 145 | 2.7% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 108 | 2.01% |

At the 2020 United States census, there were 5,379 people, 2,567 households, and 1,366 families residing in the city. At the 2010 United States census,[16] there were 6,114 people, 2,320 households, and 1,533 families residing in the city.

According to the 2019 American Community Survey, the racial and ethnic makeup was 63.0% Black and African American, 32.8% non-Hispanic white, 0.4% Asian, 2.3% two or more races, and 1.5% Hispanic and Latin American of any race.[17] In 2010, the racial makeup of the city was 35.3% White, 62.7% Black and African American, 0.20% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.2% from other races, and 1.3% from two or more races; Hispanic or Latin Americans of any race were 1.4% of the population. In 2005, 81.1% of the population over the age of five spoke only English at home, 15.9% of the population spoke French, and 2.7% spoke Louisiana Creole French.[18]

At the 2010 U.S. census, there were 2,320 households, out of which 27.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.5% were married couples living together, 28.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.9% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52 and the average family size was 3.13. In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.9% under the age of 18, 6.6% from 20 to 24, 22.8% from 25 to 44, 26.9% from 45 to 64, and 15.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.7 males. By the 2019 census estimates, the population was spread throughout 3,120 housing units and the median age was 47.5; 5.6% of the population were aged 5 and under, and 79.6% were aged 18 and older; 22.4% were aged 65 and older.[19]

In 2019, the median household income was $25,520 and 28.2% of its population lived at or below the poverty line. Males had a median income of $30,505 versus $27,167 for females. In 2010, the median income for a household in the city was $24,246 and the median income for a family was $33,009. Males had a median income of $30,710 versus $33,455 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,835. About 24.6% of families and 29.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.2% of those under age 18 and 16.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

The economy of St. Martinville is fueled by agriculture and tourism.[20] Agricultural production mainly yields crops of crawfish and sugar cane. The latter was a major commodity crop before the American Civil War, when it was dependent on enslaved labor. It has continued to be important.

Education

Public schools in St. Martin Parish are operated by the St. Martin Parish School Board. The city of St. Martinville is zoned to the Early Learning Center (Grades PK-1), St. Martinville Primary School (Grades 1-5), St. Martinville Junior High School (Grades 6-8) and St. Martinville Senior High School (Grades 9-12).[21] The Evangeline campus of Louisiana Technical College is located in St. Martinville.

Culture and arts

St. Martinville is widely considered an important site in the development of Cajun culture, and it is in the heart of Cajun Country. A multicultural community in St. Martinville, with Acadians and Cajuns, Creoles (French coming via the French West Islands - Guadeloupe, Martinique and Santo Domingo), French, Spaniards and Africans. Once New Orleans was founded and began to have epidemics, some New Orleanians escaped the city and came to St. Martinville. Its nickname, Petit Paris ("Little Paris"), dates from the era when St. Martinville was known as a cultural mecca with good hotels and a French theater, the Duchamp Opera House (founded in 1830), which featured the best operas and witty comedies.

The third oldest town in Louisiana, St. Martinville has many buildings and homes with historic architecture. The historic St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church and La Maison Duchamp on Main Street are part of the legacy of the Acadian people. The church was dedicated to Martin of Tours in France, where a St Martin de Tours church can be found. St. Martinville is the site of the "Evangeline Oak", featured in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem about the Acadian expulsion.

The city houses an African American Museum and is a posted destination on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail, which was established in 2008.[22][23]

St. Martinville is the setting of the 2013 film, Christmas on the Bayou, starring Hilarie Burton as Katherine, a divorced mother and business executive, with Tyler Hilton as Caleb, Katherine's former childhood companion. In the story line, Katherine rekindles romance and discovers where she truly belongs after she comes to St. Martinville to spend Christmas with her mother Lilly (Markie Post), and son Zack (Brody Rose). Randy Travis and Ed Asner are cast, respectively, as Mr. Greenhall and Papa Noel (the bayou Santa Claus).[24]

Notable people

- Clementine Barnabet, serial killer and mass murderer

- Calvin Borel, jockey, three-time Kentucky Derby winner.

- Jefferson J. DeBlanc, World War II ace fighter pilot and Medal of Honor recipient. Resided in St. Martinville and is buried in the town's Catholic cemetery.

- Early Doucet, wide receiver for the LSU Fighting Tigers (2004–2008) and the Arizona Cardinals (2008–2012).

- Willie Francis, survived the electric chair at age 17.

- Beverly Guirard, microbiologist, expert on vitamin B6

- Paul Jude Hardy, first Republican to be elected Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana (1988–1992).

- Jay Hebert, professional golfer, 1960 PGA Championship winner.

- Jeff Landry, Republican congressman for the Third Congressional District (2011–2013) and Attorney General of Louisiana (2016–).

- Darrel Mitchell, professional basketball player.

- Fred H. Mills, Jr., Republican state representative for St. Martin Parish.

- David Turpeau, minister and state legislator in Ohio

- Nathan Williams, zydeco accordionist and singer.

Sister cities

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- Jack A. Reynolds. "St. Martinville" entry in "Louisiana Placenames of Romance Origin." LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses #7852. 1942. p. 480.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Distance between Saint Martinville, LA and Breaux Bridge, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "Distance between Saint Martinville, LA and Lafayette, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "Distance between Saint Martinville, LA and New Iberia, LA". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "QuickFacts: St. Martinville city, Louisiana". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- "Colonial Louisiana". Louisiana State Museum. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "From Acadian to Cajun - Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "Cajuns". 64 Parishes. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "Milestones: 1801–1829 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- Grissom, Ken (July 12, 2006). "Baker First Black Mayor". Teche News – via Newspapers.com.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- "2019 Demographic and Housing Estimates". data.census.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "Data Center Results". Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- "Geography Profile: St. Martinville city, Louisiana". data.census.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- "St. Martinville". Louisiana Official Travel and Tourism Information. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- Archived August 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Kimberly Quillen, "African American Heritage Trail unveiled in New Orleans this morning", Times Picayune, February 27, 2008, accessed January 17, 2015

- "A Story Like No Other: African American Heritage Trail", website

- "Christmas on the Bayou". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

External links

- City of St. Martinville

- "On The Road To St. Martinville, Louisiana," an on-line photo journal of historic St. Martinville, Louisiana.