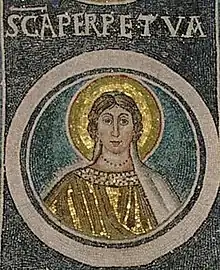

Perpetua and Felicity

Perpetua and Felicity (Latin: Perpetua et Felicitas) were Christian martyrs of the 3rd century. Vibia Perpetua was a recently married, well-educated noblewoman, said to have been 22 years old at the time of her death, and mother of an infant son she was nursing.[6] Felicity, a slave woman imprisoned with her and pregnant at the time, was martyred with her. They were put to death along with others at Carthage in the Roman province of Africa.

Perpetua and Felicity | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The martyrdom of Perpetua, Felicitas, Revocatus, Saturninus and Secundulus, from the Menologion of Basil II (c. 1000 AD) | |

| Martyrs | |

| Born | c. 182[1] |

| Died | c. 203 (aged 20–21) Carthage, Roman province of Africa |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | Roman Catholic Church:

Anglican Communion

|

| Patronage |

|

The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity narrates their death. According to the passion narrative, five people were arrested and executed at the military games in celebration of the Emperor Septimius Severus's birthday. Along with Felicitas and Perpetua, these included two free men, Saturninus and Secundulus, and an enslaved man named Revocatus; all were catechumens or Christians being instructed in the faith but not yet baptized. To this group of five was added a further man named Saturus, who voluntarily went before the magistrate and proclaimed himself a Christian. Perpetua's first person narrative was published posthumously as part of the Passion.[7][8]

Imprisonment

Perpetua's account opens with conflict between her and her father, who wishes her to recant her belief. Perpetua refuses, and is soon baptized before being moved to prison. Perpetua was imprisoned in Carthage in the days leading up to her martyrdom. She described these days and what she endured in her diary.[6]

Perpetua described the physical and emotional torments that she suffered in the prison leading up to her martyrdom. Perpetua suffered physically due to the heat, rough prison guards, and the cessation of regular breastfeeding. Perpetua also described how the prison conditions improved after she was able to bribe the guards so that she and the other martyrs were moved to another part of the prison, with her infant. Her physical torment was also eased after she was able to breastfeed her child.[9] Perpetua described bodily ailments in detail and the most common in her narrative was the cycle of pain and relief she would feel in her breasts.

At the encouragement of her brother, Perpetua asks for and receives a vision, in which she climbs a dangerous ladder to which various weapons are attached. At the foot of a ladder is a serpent, which is faced first by Saturus and later by Perpetua. The serpent does not harm her, and she ascends to a garden. At the conclusion of her dream, Perpetua realizes that the martyrs will suffer.

The day before her martyrdom, Perpetua envisions herself defeating a savage Egyptian and interprets this to mean that she would have to do battle not merely with wild beasts, but with the Devil himself.

Veneration

In Carthage a basilica was erected over the tomb of the martyrs, the Basilica Maiorum, where an ancient inscription bearing the names of Perpetua and Felicitas has been found.

Saints Felicitas and Perpetua are among the martyrs commemorated by name in the Roman Canon of the Mass.

The feast day of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas, 7 March, was celebrated across the Roman Empire and was entered in the Philocalian Calendar, the 4th-century calendar of martyrs venerated publicly in Rome. When Saint Thomas Aquinas's feast was inserted into the Roman calendar, for celebration on the same day, the two African saints were thenceforth only commemorated. The Tridentine Calendar, established by Pope Pius V, continued to commemorate the two until the year 1908, when Pope Pius X brought the date for celebrating them forward to 6 March.[10] In the 1969 revision of the General Roman Calendar, the feast of Saint Thomas Aquinas was moved, and that of Saints Perpetua and Felicity was restored to their traditional 7 March date.[11]

Other Churches, including the Lutheran Church and the Episcopal Church, commemorate these two martyrs on 7 March, never having altered the date to 6 March. The Anglican Church of Canada, however, historically commemorated them on 6 March (The Book of Common Prayer, 1962), but have since changed to the traditional 7 March date (Book of Alternative Services, 1985).

Perpetua and Felicity are remembered in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church on 7 March.[12][13]

In the Eastern Orthodox Church the feast day of Saints Perpetua of Carthage and the catechumens Saturus, Revocatus, Saturninus, Secundulus, and Felicitas is 1 February.[3][4]

References

- Salisbury, Joyce Ellen (3 March 2019). "Perpetua:: Christian Martyr". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "The Calendar" (PDF). Church of England. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ἡ Ἁγία Περπέτουα ἡ Μάρτυς καὶ οἱ σὺν αὐτῇ. 1 Φεβρουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- Martyr Perpetua, a woman of Carthage. OCA – Feasts and Saints.

- Lutheran Woman Today, Volume 11. Publishing House of Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 1998.

Perpetua is commemorated by the church on March 7.

- MELISSA, PEREZ. VIBIA PERPETUA'S DIARY: A WOMAN'S WRITING IN A ROMAN TEXT OF ITS OWN (PDF) (Thesis). Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

She was "of good family, recently married, and well educated with an infant son at her breast."

- Heffernan, Thomas J. (2012). The passion of Perpetua and Felicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199777570.001.0001. ISBN 9780199777570.

- Gold, Barbara K. (2018). Perpetua: athlete of god. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780195385458.001.0001. ISBN 9780195385458.

- Dova, Stamatia (2017). "Lactation Cessation and the Realities of Martyrdom in the Passion of Saint Perpetua". Illinois Classical Studies. 42: 245–265. doi:10.5406/illiclasstud.42.1.0245. S2CID 164888397 – via JSTOR.

- "Calendarium", p. 89.

- "Calendarium", p. 119.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 1 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-234-7.