Sakhalin-I

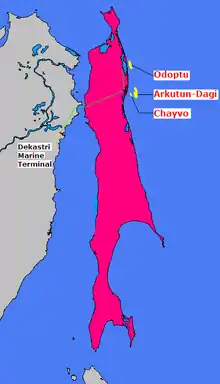

The Sakhalin-I (Russian: Сахалин-1) project, a sister project to Sakhalin-II, is a consortium for production of oil and gas on Sakhalin Island and immediately offshore. It operates three fields in the Okhotsk Sea: Chayvo, Odoptu and Arkutun-Dagi.[1]

| Sakhalin-I project Chayvo, Odoptu, Arkutun-Dagi fields | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Russia |

| Region | Sakhalin |

| Offshore/onshore | offshore |

| Operator | Exxon Neftegas |

| Partners |

|

| Production | |

| Current production of oil | 250,000 barrels per day (~1.2×107 t/a) |

| Estimated oil in place | 2,300 million barrels (~3.1×108 t) |

| Estimated gas in place | 17,100×109 cu ft (480×109 m3) |

In 1996, the consortium completed a production-sharing agreement between the Sakhalin-I consortium, the Russian Federation and the Sakhalin government. The consortium was managed and operated by Exxon Neftegas Limited (ENL), a unit of ExxonMobil,[1] until Exxon's withdrawal in March 2022 following the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine.[2] The Russian government froze Exxon's investment in August 2022 and ordered its transfer to a newly created Russian company the following October.[3]

Since 2003, when the first Sakhalin-1 well was drilled, six of the world's 10 record-setting extended reach drilling wells have been drilled at the fields of the project, using the Yastreb rig. It has set multiple industry records for length, rate of penetration and directional drilling. On 27 August 2012, Exxon Neftegas beat its previous record by completing Z-44 Chayvo well. This ERD well reached a measured total length of 12,376 meters (40,604 ft), making it the longest well in the world.[4][5] In November 2017, the record well reached 15 kilometers (49,000 ft) long.[6]

History

Sakhalin I's fields Chayvo, Arkutun-Dagi and Odoptu were discovered by the Soviets some 20 years before the Production Sharing Agreement of 1996. However these fields had never been properly assessed and a reevaluation of the commercial viability had to be carried out. To do this, factors such as the reservoir quality, producibility and well locations had to be found. 3-D seismic is the most common way to determine much of this however shallow gas reservoirs interfered with the seismic signals and blurred the images somewhat.[1]

Two campaigns of 3-D seismic were carried out along with a number of appraisal wells into the Arkutun-Dagi and Chayvo fields. The results were initially average from the appraisal wells with hydrocarbons being successfully tested, but there was still a large amount of uncertainty involved with the project. However, in late 1998, a revaluation of the 3-D seismic data using the most advanced seismic-visualization techniques then available indicated that the hydrocarbon depth on the edge of the field could be significantly deeper than first thought. In 2000, the Chayvo 6a delineation well confirmed what was suspected, a 150 meters (490 ft) oil column. This provided the certainty that the field was commercially viable in the hostile environment with a potential to be a 1-billion-barrels (160×106 m3) field.[1]

In 2007, the project set a world record when extended-reach drilling (ERD) well Z-11 reached 11,282 meters (37,014 ft).[7][8] That record was broken in early 2008 with extended-reach well Z-12 reaching 11,680 meters (38,320 ft).[8] Both extended-reach wells are in the Chayvo field and reach over 11 kilometers (6.8 mi).[8] As of early 2008, the Chayvo field contains 17 of the world's 30 longest extended-reach-drilling wells.[8] However, in May 2008, both world records of ERD well were surpassed by the GSF Rig 127 operated by Transocean, which drilled the ERD well BD-04A in the Al Shaheen oil field in Qatar. This ERD well was drilled to a record measured length of 12,289 meters (40,318 ft) including a record horizontal reach of 10,902 meters (35,768 ft) in 36 days.[9]

On 28 January 2011, Exxon Neftegas, operator of the Sakhalin-1 project, drilled the then world's longest extended-reach well. It has surpassed both the Al Shaheen well and the previous decades-long leader Kola Superdeep Borehole as the world's longest borehole. The Odoptu OP-11 Well reached a measured total length of 12,345 meters (40,502 ft) and a horizontal displacement of 11,475 meters (37,648 ft). Exxon Neftegas completed the well in 60 days.[10]

On 27 August 2012, Exxon Neftegas beat its own record by completing Z-44 Chayvo well. This ERD well reached a measured total length of 12,376 meters (40,604 ft).[5]

Since the start of drilling in 2003 to 2017, Sakhalin-1 has drilled 9 of the 10 longest wells in the world. Since 2013, the project has set five records for drilling wells with the deepest depths in the world. In April 2015, the O-14 production well was drilled, with length of 13.5 kilometers (44,000 ft), in April 2014 the Z-40 well was completed with a length of 13 kilometers (43,000 ft), in April and June 2013 - the Z-43 and Z-42 wells 12.45 kilometers (40,800 ft) and 12.7 kilometers (42,000 ft) long, respectively. In November 2017 the record well reached 15 kilometers (49,000 ft) long.[6][11]

Production from Sakhalin 1 halted in May 2022, when operator Exxon Neftegaz declared force majeure at the project in response to international sanctions imposed on Russia after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February. In October 2022 Vladimir Putin instructed authorities to disband Exxon Neftegaz and transfer the project and all of its assets and equipment to a new operator, in which the government will hold a controlling 80% shareholding for an initial period of one month. The Exxon Neftegaz shareholding may be sold at an auction to a third party if authorities discover any damage to the development.[12]

After handing over operations of Sakhalin 1 to a Rosneft subsidiary production was re-established with an output of 140,000 barrels per day (22,000 m3/d)-150,000 barrels per day (24,000 m3/d) expected to rise to 220,000 barrels per day (35,000 m3/d) eventually.[13]

Development

The three fields will be developed in this order: Chayvo, Odoptu and Arkutun-Dagi. The total project is estimated to cost US$10–12 billion, making it the largest direct investment in Russia from foreign sources. It is also estimated that nearly 13,000 jobs will be created either directly or indirectly. Approximately $2.8 billion has already been spent, which helped lower unemployment and improved the tax base of the regional government. The fields are projected to yield 2.3 billion barrels (370×106 m3) of oil and 17.1 trillion cubic feet (480×109 m3) of natural gas.[1]

In 2007, the consortium reached its production goal of 250,000 barrels per day (40,000 m3/d) of oil.[14] In addition, natural gas production for the peak winter season in 2007 was 140 million cubic feet per day (4.0×106 m3/d).[14]

The first rig is in place for Sakhalin-I, Yastreb, is the most powerful land rig in the world. Parker Drilling Company is the operator of the 52 meters (171 ft) high rig. Although the rig is land based it will drill more than 20 extended-reach wells 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) horizontally out into the Sea of Okhotsk, and 2,600 meters (8,500 ft) in depth. This land-based offshore drilling arrangement is needed because the Sea of Okhotsk is frozen about four months out of the year. The rig is designed to be resistant to the earthquakes that frequent the area, and operate in the −40 °C (−40 °F) temperatures that can occur in the winter.[1]

As part of the project, Russia is in the process of building a 220-kilometre (140 mi) pipeline across the Tatar Strait from Sakhalin Island to De-Kastri oil terminal on the Russian mainland. From De-Kastri it will be loaded onto tankers for transport to East Asian markets.[1]

Consortium

Prior to March 2, 2022 the consortium consisted of:

- 30.0% - ExxonMobil (United States)

- 30.0% - Sakhalin Oil & Gas Development Co (Japan)

- 20.0% - ONGC Videsh Ltd. (India)

- 11.5% - Sakhalinmorneftegas-Shelf (Russia)

- 8.5% - RN-Astra (Russia)

Environment

Scientists and environmental groups have voiced concern that the Sakhalin-I oil and gas project in the Russian Far East, operated by an ExxonMobil subsidiary Exxon Neftegas, threatens the critically endangered western gray whale population.[16][17] Approximately 130 western gray whales remain, of which only 30-35 are reproductive females. These whales only feed during the summer and autumn, in feeding grounds which happen to lie adjacent to Sakhalin-I project onshore and offshore facilities and associated activities along the northeast coast of Sakhalin Island.[18] Particular concerns were caused by the decision to construct a pier and to start shipping in Piltun Lagoon.[19]

Since 2006, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has convened the Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel (WGWAP), consisting of marine scientists who provide expert analysis and advice concerning impacts on the endangered western gray whale population from oil and gas projects in the area, including Sakhalin-I.[20] In February 2009, the WGWAP reported that the number of western gray whales observed in the near-shore (primary) feeding area had significantly declined in the summer of 2008, which coincides with industrial activities conducted by ENL (and other companies) in the area. The WGWAP suggested a moratorium on all industrial activities in the area until their effects had been studied or plans made to mitigate any negative effects of industrial activity had been implemented.[21] Cooperation of Sakhalin Energy-ENL with the scientific panel investigating gray whales was hampered by confidentiality agreements and by ENL's lack of motivation to cooperate with the process.[22]

ExxonMobil has responded that since 1997 the company has invested over $40 million to the western whale monitoring program.[23]

In June 2018 the Sakhalin Environment Watch reported a huge die off of Pacific herring fish at the River Kadylaniy near Sakhalin's pipeline outlet.[24] Low oxygen concentrations, related to oil production work has been suggested as the culprit.[25]

ExxonMobil withdrawal

On March 1, 2022, ExxonMobil, the principal operator of the Sakhalin I project, announced its complete withdrawal from the project. A company press release cited the war in Ukraine and the desire to comply with Western sanctions as reasons for the termination of operations, along with a desire to protect investors' assets. In the same document, ExxonMobil announced its intent to end any participation the company had or has planned in the country.[26]

References

- "Sakhalin-1: A New Frontier" - PennWell Custom Publishing (c/o of ExxonMobil)

- "ExxonMobil to discontinue operations at Sakhalin-1, make no new investments in Russia". ExxonMobil. Retrieved 2022-03-02.

- "Putin Orders Sakhalin-1 Project Transferred to Russian Entity". Bloomberg US Edition. October 8, 2022. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- "Z-44 Chayvo Well: The Deepest Oil Extraction (Infographic)". 24 March 2017.

- Sakhalin-1 Project Breaks Own Record for Drilling World`s Longest Extended-Reach Well

- Новый мировой рекорд «Сахалин-1»

- "ExxonMobil Announces Drilling of World-Record Well". ExxonMobil. Business Wire. 24 April 2007.

- Watkins, Eric. - "ExxonMobil drills record extended-reach well at Sakhalin-1" - Oil & Gas Journal - (c/o mapsearch.com) - 11 February 2008

- Transocean Ltd. Press Release (2008). "Transocean GSF Rig 127 Drills Deepest Extended-Reach Well" Archived 2010-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 2009-10-21

- Sakhalin-1 Project Drills World's Longest Extended-Reach Well Archived 2011-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Project history

- Russia takes control of Sakhalin 1 oil and gas project

- Russia's Sakhalin-1 near full oil output after Exxon exit -source

- "Sakhalin-1 Project Production Goal Achieved". ExxonMobil. Business Wire. 14 February 2007.

- Project Information Overview - Sakhalin-1 Project Website

- Sapulkas, Agis (2009-04-24). "Western Gray Whales Get a Break From Noisy Oil Development". Environmental News Service. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- "Gray whales granted rare reprieve". BBC News. April 24, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- "IUCN - Initiative Background". International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on 2010-07-24.

- "Exxon operations threaten endangered western gray whales in Russia". World Wild Fund. 2016-07-11. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- "Western Gray Whale Conservation Initiative: History of Engagement". www.iucn.org. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009.

- "17 Update on Proposed Activity on the Sakhalin Shelf". Report of the Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel at its Fifth Meeting (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. December 2008. pp. 31–33. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- "18 Explicit Discussion of WGWAP modus operandi, Potential Revision of ToR, Structure and Schedule of Panel Meetings". Report of the Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel at its Fifth Meeting (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. December 2008. pp. 33–36. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- Sheridan, Kerry (2016-07-11). "Deal with oil giant helps near-extinct whale recover". phys.org. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- "Hundreds of tons of dead herring wash up on Russian coast". euronews.com. euronews. 2018-06-13.

- "The industrial facilities of Exxon Neftegas Limited could have been involved in the death of herring in the Piltun Bay". ecosakh.ru. 2018-07-09.

- ExxonMobil Press Release (2022). "ExxonMobil to discontinue operations at Sakhalin-1, make no new investments in Russia" Archived 2022-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 2022-04-27

External links

- Sakhalin-1 Project website

- Parker Drilling

- Sakhalin Factsheet - at the Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration

- Сахалин-1 (Russian)