Sal·la

Sal·la (Latin: Sanla) was the Bishop of Urgell from 981 to 1010, and "one of the first Catalan figures whose own words" survive sufficiently "to give colour to his personality and actions", although all of the words attributed to him were written down by scribes.[1] He receives mention in some sixty-three surviving contemporary documents. As bishop, Sal·la dated documents by the reign of Hugh the Great. Although his episcopate largely preceded the Peace of God movement in Catalonia, his excommunication of high-ranking public figures during a church–state dispute in 991 anticipated it.[2] He also pioneered feudal practices such as the granting of fiefs and was frequently "ahead of the feudalising wave".[3]

Feudal politics

Sal·la was the son of Isarn, semi-independent viscount of Conflent. His brother Bernat and Bernat's son Arnau, both viscounts in succession after Isarn, make no appeal to comital authority in all their surviving documents. Sal·la was perhaps named after his uncle Sal·la, founder of Sant Benet de Bages and "perhaps the greatest frontier magnate in tenth-century Catalonia after the counts".[4] Throughout their lives, Sal·la and his brother Bernat endeavoured by exchanges and divisions of their patrimony (inherited estates) to consolidate the former's lands in Urgell and the latter's in Conflent and Ausona, around their respective power bases.[5]

Sal·la was also related, it is not known how, to the viscounts of Ausona.[4] All the bishops of Urgell from 942 to 1040 were members of this same extended family.[6] By 974 he was an archdeacon in the Cathedral of Urgell.[4] At a date unknown, after Sal·la became bishop, the viscount of Urgell, Guillem, swore an oath of fealty to Sal·la personally rather than to the cathedral or its patron, the Virgin. This was commonplace at a later date, but such oaths to the bishop directly are unusual among the documents of tenth-century Catalonia, and Guillem's may be the earliest a record of which survives.[7]

There are three surviving charters, the first of their kind in Catalonia, which show Sal·la selling or giving back land that had first been donated to the cathedral by the one receiving it back, who owed for it an annual render in wax.[3] The amount is uniform across all the donations and is the same as in a further five charters recording gifts to the cathedral for which the original owner retained usufruct for life at the price of an annual render in wax. These all appear to be simple precarial arrangements, then already well known in the rest of Francia and in Italy, where scribes had already developed formulae (absent in these charters of Urgell) distinct from those for sales and grants of usufruct. In two of these documents the tenant was required to have only one lord (that is, the bishop), which is unlike the case of typical precariae and more like that of homage later developed.[3] By thus attaching free peasants to himself, one historian writes, "Sal·la was creating seigneurial dependants thirty years before this process is usually thought to have properly begun".[8]

Fortification of the diocese

The earliest fortification known to have been possessed by the see of Urgell was that Sanaüja in the Segarra, which was owned by Sal·la's predecessor, Guisad II (942–79/80), in 951, as mentioned in the confirmation he received from Pope Agapetus II. How the diocese of Urgell came to possess this site is unknown, but many of the castles acquired under Sal·la originally belonged to Borrell II, Count of Barcelona and Count of Urgell. For example, in 986 one Vidal granted the diocese the fortress at Figuerola, which he had originally purchased from Borrell, and received it back to be held by him and his son against the payment of a census.[9]

The castle of Queralt was sold by Borrell to the viscount of Barcelona in 976. In 1002 Sal·la made a successful claim of rights to it on behalf of his see, although the origin of these rights is not known. In 1007 Sal·la acquired for Urgell the castle of Conques, which was left to it by Borrell's son and successor in the county of Urgell, Ermengol I, in his testament. Most of these grants of castles were made directly to the bishopric and not to the bishop, although this tendency changed after Sal·la's death.[9]

Conflicts with Count Borrell

As bishop, Sal·la acquired the castle of Carcolze(s) from Count Borrell, whom Sal·la refers to as "my lord" in his charters, in compensation for his half of the castle of Clarà, which Borrell had withheld, contrary to their agreement, which Sal·la refers to as hoc convencione ("this convention").[10] Clarà was then on the frontier between Catalonia and the depopulated valley of the Ebro, and it belonged in Sal·la's family; his brother Bernat owned the other half of it at his death in 1003. In 995 Sal·la sold Carcolzes to his cathedral's sacristan, Bonhom, for five hundred solidi of produce. Within a year Bonhom had sold it at cost to Guillem de Castellbò, the viscount of Urgell, who in turn sold it for the same price back to Sal·la, who finally donated it to his diocese and placed it in the hands of his nephew Ermengol, archdeacon of the cathedral since at least 996.[11]

Sometime before 993, when Borrell imprisoned Sendred, one of the archdeacons of Urgell, in order to extort from him an allod at Somont, Sal·la gained his release by claiming the alod belonged to the church. This appropriation of allodial land in Andorra was legitimised in 1003 in a charter issued by Sendred by which he and his wife Ermeriga and their heirs were to hold it in benefice from the Virgin, patron saint of the see of Urgell.[12]

Dispute with Berga and Cerdagne

In 991, Sal·la, along with bishops Vives of Barcelona and Aimeric of Roda, pronounced excommunication on Arnau and Radulf, the two advisors of Countess Ermengarda, the widow of Oliba Cabreta and regent for her three sons: Bernard I of Besalú, Wifred II of Cerdagne, and Oliba of Berga. The cause of the excommunication was the appropriation of ecclesiastical properties in several parishes in Berga and Cerdagne. The initiative in the act of discipline was taken by Sal·la, whose parishes were the ones concerned, and both the bull of excommunication and the encyclical justifying his actions to his fellow bishops survive.[13] On this occasion he is said to have argued that "excommunication was the weapon of the Church where the sword was the weapon of the layman".[14] Perhaps this drastic measure was designed "to remind his suffragan priests in the affected areas that they had another master as well as the counts".[2]

Whether the ban had the result of rectifying the diocese and the countess is unknown, as there are no surviving acts of Sal·la's in Berga or Cerdagne after 984, and only one act of consecration performed by him after 990 has survived. A papal bull from Sylvester II, dated 1001, confirms the churches of Berga and Cerdagne to the see of Urgell. In 1004 Sal·la sold property in Berga, but it may have been the purchaser and not the church who was able to control the land. Neither the papal confirmation of 1001 nor the diocesan sale of 1004 evidence the resolution of the dispute of 991.[2]

Episcopal succession

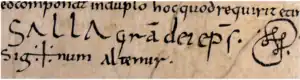

The documents recording both Sal·la's will and its execution have survived. They left most of his property either to his cathedral or to his nephew Ermengol, who succeeded him in the episcopal office.[5] Sometime between 992, when Ermengol, second son of Borrell II, inherited the county of Urgell from his father, and the death of Viscount Bernat of Conflent in 1003, Sal·la came to an agreement (convenientia) with the new count of Urgell whereby the latter would support the candidacy of bishop's nephew to succeed him and in return receive a large sum as payment for performing the act of investiture within ten days of being notified by the bishop of his election.[15] The document is undated—as is typical of convenientiae—but it was drawn up while Bernat was still alive and it carefully avoids any payment for securing Ermengol's succession to the bishopric, which would have been simony and against canon law. That the count was expected to perform the investiture suggests that he regarded it as his customary right.[16] Sal·la extracted from the count an oath not to harm the bishop or the bishopric, and the count in turn demanded a future oath from Ermengol—"that I may have faith (fidelitas) in him" in the words of the agreement. The price of his support was "100 pesas, or equivalent pesetas, or bullion worth 200 pesas instead of those 100 pesas" to be collected from either Ermengol himself or "Bishop Sal·la or his brother Bernat or any of the kinsmen or friends of that same cleric Ermengol written above".[17]

By 1007 Sal·la had named Ermengol his coadjutor. His health may have been ailing, for in that year he drew up his will.[18] That same year, however, he travelled to the County of Pallars, where he and "Bishop Ermengol his coadjutor" signed the act of union of the monasteries of Sant Pere de Burgals in Pallars and Notre Dame de la Grasse north of the Pyrenees, right beneath the signature of Count Sunyer.[19] Sal·la died in 1010 during a raid on Córdoba and was succeeded by Ermengol as planned.[20]

Notes

- Jarrett, 299.

- Jarrett, 306.

- Jarrett, 311.

- Jarrett, 296–97.

- Jarrett, 307.

- Sal·la's predecessor, Guisad II, was a brother of Guadall II, viscount of Ausona, and the successor of Sal·la's nephew, Eribau, was a son of Ramon, viscount of Ausona, and himself served as viscount there from about 1033, cf. Kosto, 187 n102.

- About this Jarrett, 310, writes: "the numerous early oaths to bishops of Urgell are all preserved only as copies despite the voluminous number of originals in the archive, suggesting that they were not thought important to retain". Kosto, 55, presents a chart of the earliest written oaths from the Catalan counties, showing that only two may pre-date Guillem's: the oath of Count Ermengol I of Urgell to Bishop Sal·la (992x1003) and an oath securely dated to 987 by one Ennec Bonfill to Fruia, Bishop of Vic.

- Jarrett, 312.

- Kosto, 187.

- Kosto, 40, quotes that passage, which is found only in charters surviving as early modern copies, in full: "Tim and again I [Sal·la] granted additional deadlines for him [Borrell] to redeem what he had handed over to me in the agreement" (iterum atque iterum dedi ei alios placitos atque alios ut hoc convencione de supradicta omnia quod michi tradidit redimere fecisset).

- Jarrett, 299–301, who quotes the charter of 995 at length. The scribe of this act was Lleopard.

- Jarrett, 301–3, who also quotes the charter of 1003 at length. The scribe of this charter was the priest Durabiles.

- Jarrett, 304–5, who quotes from the encyclical extensively.

- Jarrett, 313, based on Bowman, 71 n48.

- Kosto, 57.

- Jarrett, 308–9.

- Quoted in Jarrett, 309 n50: pessas .C., aut pessatas valibiles, aut pigdus valibiles de pessas .CC. pro ipsas pessas .C. and Sallane episcopo aut Bernatus fratri suo aut aliquis de ex parentibus vel amicis de isto Ermengaude clericus super scripto.

- Jarrett, 312–13.

- Jarrett, 309–10.

- Bowman 2002, 3–5.

Bibliography

- C. Baraut (ed.), “Les actes de consagracions d’esglésies del bisbat d’Urgell (segles IX–XII)”, Urgellia, 1 (1978): 11–182.

- C. Baraut (ed.), “Set actes més de consagracions d’esglésies del bisbat d’Urgell (segles IX–XII)”, Urgellia, 2 (1979): 481–88.

- C. Baraut (ed.), “Els documents, dels Anys 981–1010, de l’Arxiu Capitular de la Seu d’Urgell”, Urgellia, 3 (1980): 7–166.

- Jeffrey A. Bowman, “The Bishop Builds a Bridge: Sanctity and Power in the Medieval Pyrenees”, The Catholic Historical Review, 88, 1 (2002): 1–16.

- Jeffrey A. Bowman, “Shifting Landmarks: Property, Proof, and Dispute in Catalonia around the Year 1000”, Conjunctions of Religion and Power in the Medieval Past, Ithaca: 2004.

- Jonathan Jarrett, “Sales, Swindles and Sanctions: Bishop Sal·la of Urgell and the Counts of Catalonia”, International Medieval Congress, Leeds, 11 July 2005, published in the Appendix, Pathways of Power in late-Carolingian Catalonia, PhD dissertation, Birkbeck College (2006).

- Adam J. Kosto, Making Agreements in Medieval Catalonia: Power, Order, and the Written Word, 1000–1200, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- E. Magnou-Nortier, “The Enemies of the Peace: Reflections on a Vocabulary, 500–1100”, trans. A. G. Remensnyder in T. Head and R. Landes, The Peace of God: Social Violence and Religious Responses in France around the Year 1000, Ithaca: 1992, 58–79.

- M. Rovira, “Noves dades sobre els vescomtes d’Osona-Cardona”, Ausa, 9, 98 (1981): 249–60.