Fire salamander

The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) is a common species of salamander found in Europe.

| Fire salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Salamandra |

| Species: | S. salamandra |

| Binomial name | |

| Salamandra salamandra | |

| |

| Distribution of fire salamander | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

It is black with yellow spots or stripes to a varying degree; some specimens can be nearly completely black while on others the yellow is dominant. Shades of red and orange may sometimes appear, either replacing or mixing with the yellow according to subspecies.[2] This bright coloration is highly conspicuous and acts to deter predators by honest signalling of its toxicity (aposematism)[3] Fire salamanders can have a very long lifespan; one specimen lived for more than 50 years in Museum Koenig, a German natural history museum.

Habitat, behavior and diet

Fire salamanders live in the forests of central Europe and are more common in hilly areas. They prefer deciduous forests since they like to hide in fallen leaves and around mossy tree trunks. They need small brooks or ponds with clean water in their habitat for the development of the larvae. Whether on land or in water, fire salamanders are inconspicuous. They spend much of their time hidden under wood or other objects. They are active in the evening and the night, but on rainy days they are active in the daytime as well.[4]

The diet of the fire salamander consists of various insects, spiders, millipedes, centipedes,[5] earthworms and slugs, but they also occasionally eat newts and young frogs. In captivity, they eat crickets, mealworms, waxworms and silkworm larvae. Small prey will be caught within the range of the vomerine teeth or by the posterior half of the tongue, to which the prey adheres. It weighs about 40 grams. Compared to other salamanders in the region like Luschan's salamander, the fire salamander has been shown to be larger and appears to have a more solid pectoral girdle. Additionally, it has a longer pectoral girdle than Luschan’s salamander. [6] The fire salamander is one of Europe's largest salamanders[7] and can grow to be 15–25 centimetres (5.9–9.8 in) long.[8]

Reproduction

Males and females look very similar, except during the breeding season, when the most conspicuous difference is a swollen gland around the male's vent. This gland produces the spermatophore, which carries a sperm packet at its tip. The courtship happens on land. After the male becomes aware of a potential mate, he confronts her and blocks her path. The male rubs her with his chin to express his interest in mating, then crawls beneath her and grasps her front limbs with his own in amplexus. He deposits a spermatophore on the ground, then attempts to lower the female's cloaca into contact with it. If successful, the female draws the sperm packet in and her eggs are fertilized internally. The eggs develop internally and the female deposits the larvae into a body of water just as they hatch. In some subspecies, the larvae continue to develop within the female until she gives birth to fully formed metamorphs. Breeding has not been observed in neotenic fire salamanders.

In captivity, females may retain sperm long-term and use the stored sperm later to produce another clutch. This behavior has not been observed in the wild, likely due to the ability to obtain fresh sperm and the degradation of stored sperm.[9]

Toxicity

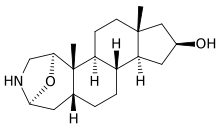

The fire salamander's primary alkaloid toxin, samandarin, causes strong muscle convulsions and hypertension combined with hyperventilation in all vertebrates. Through an analysis of the European fire salamander’s skin secretions, scientists have determined that another alkaloid, such as samandarone, is also released by the salamander.[10] These steroids can be swabbed from the salamander’s parotid glands. Samandarine was often the dominant alkaloid present but the ratio varied between salamanders. This ratio, however, was not shown to be sex dependent.<ref name=Toxicon> Larvae do not produce these alkaloids. Upon maturity, ovaries, livers, and testes appear to produce these defensive steroids. The poison glands of the fire salamander are concentrated in certain areas of the body, especially around the head and the dorsal skin surface. The coloured portions of the animal's skin usually coincide with these glands. Compounds in the skin secretions may be effective against bacterial and fungal infections of the epidermis; some are potentially dangerous to human life.

Distribution

Fire salamanders are found in most of southern and central Europe. They are most commonly found at altitudes between 250 metres (820 ft) and 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), only rarely below (in Northern Germany sporadically down to 25 metres (82 ft)). However, in the Balkans or Spain they are commonly found in higher altitudes as well.

Subspecies

Several subspecies of the fire salamander are recognized. Most notable are the subspecies fastuosa and bernadezi, which are the only viviparous subspecies – the others are ovoviviparous.

- S. s. alfredschmidti

- S. s. almanzoris

- S. s. bejarae

- S. s. bernardezi

- S. s. beschkovi

- S. s. crespoi

- S. s. fastuosa (or bonalli) – yellow-striped fire salamander

- S. s. gallaica – Galician fire salamander

- S. s. gigliolii

- S. s. morenica

- S. s. salamandra – spotted fire salamander, nominate subspecies

- S. s. terrestris – barred fire salamander

- S. s. werneri

Some former subspecies have been lately recognized as species for genetic reasons.

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Orange morph

Orange morph

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Salamandra salamandra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T59467A79323745. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T59467A79323745.en. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- Francis, Eric T.B. (1934). "The anatomy of the Salamander". Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Caspers, Barbara A. (30 June 2020). "Developmental costs of yellow colouration in fire salamanders and experiments to test the efficiency of yellow as a warning colouration". Amphibia-Reptilia. 41 (3): 373–385. doi:10.1163/15685381-bja10006.

- Tanner, Vasco M.; Wood, Stephen L. (1958). "Salamander". The Great Basin Naturalist. Phovo (Utah): Brigham Young University. pp. 97ff. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Sydlowski, Rose. "Salamandra salamandra". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- Özeti, Neclâ (1967). "The Morphology of the Salamander Mertensiella luschani ( Steindachner ) and the Relationships of Mertensiella and Salamandra". American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists ( ASIH ): 287–298.

- "Bsal". www.ravon.nl. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- Griffiths, R (1996). Newts and Salamanders of Europe. London: Academic Press.

- Steinfartz, S.; Stemshorn, K.; Kuesters, D.; Tautz, D. (30 November 2005). "Patterns of multiple paternity within and between annual reproduction cycles of the fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) under natural conditions". Journal of Zoology. 268 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2005.00001.x.

- Mebs, Dietrich; Pogoda, Werner (1 April 2005). "Variability of alkaloids in the skin secretion of the European fire salamander (Salamandra salamadra [sic] terrestris)". Toxicon. 45 (5): 603–606. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.01.001. PMID 15777956.

Further reading

- Manenti, R.; Ficetola, G. F.; De Bernardi, F. (February 2009). "Water, stream morphology and landscape: complex habitat determinants for the fire salamander Salamandra salamandra". Amphibia-Reptilia. 30 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1163/156853809787392766.

- Schmidt, B. R., Schaub, M., and Steinfartz, S. (2007). "Apparent survival of the salamander Salamandra salamandra is low because of high migratory activity". Frontiers in Zoology 4:19.

External links

- Caudata.org entry for Salamandra

- Fantastic Fire Salamanders – Salamandra Salamandra, BioFresh Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities.