Saltwater intrusion

Saltwater intrusion is the movement of saline water into freshwater aquifers, which can lead to groundwater quality degradation, including drinking water sources, and other consequences. Saltwater intrusion can naturally occur in coastal aquifers, owing to the hydraulic connection between groundwater and seawater. Because saline water has a higher mineral content than freshwater, it is denser and has a higher water pressure. As a result, saltwater can push inland beneath the freshwater.[1] In other topologies, submarine groundwater discharge can push fresh water into saltwater.

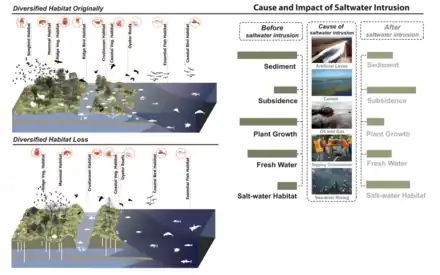

Certain human activities, especially groundwater pumping from coastal freshwater wells, have increased saltwater intrusion in many coastal areas. Water extraction drops the level of fresh groundwater, reducing its water pressure and allowing saltwater to flow further inland. Other contributors to saltwater intrusion include navigation channels or agricultural and drainage channels, which provide conduits for saltwater to move inland. Sea level rise caused by climate change also contributes to saltwater intrusion.[2] Saltwater intrusion can also be worsened by extreme events like hurricane storm surges.[3]

Hydrology

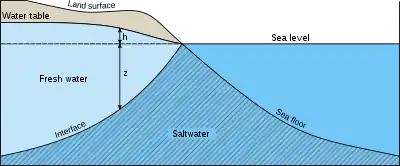

At the coastal margin, fresh groundwater flowing from inland areas meets with saline groundwater from the ocean. The fresh groundwater flows from inland areas towards the coast where elevation and groundwater levels are lower.[2] Because saltwater has a higher content of dissolved salts and minerals, it is denser than freshwater, causing it to have a higher hydraulic head than freshwater. Hydraulic head refers to the liquid pressure exerted by a water column: a water column with higher hydraulic head will move into a water column with lower hydraulic head, if the columns are connected.[4]

The higher pressure and density of saltwater causes it to move into coastal aquifers in a wedge shape under the freshwater. The saltwater and freshwater meet in a transition zone where mixing occurs through dispersion and diffusion. Ordinarily the inland extent of the saltwater wedge is limited because fresh groundwater levels, or the height of the freshwater column, increases as land elevation gets higher.[2]

Causes

Groundwater extraction

Groundwater extraction is the primary cause of saltwater intrusion. Groundwater is the main source of drinking water in many coastal areas of the United States, and extraction has increased over time. Under baseline conditions, the inland extent of saltwater is limited by higher pressure exerted by the freshwater column, owing to its higher elevation. Groundwater extraction can lower the level of the freshwater table, reducing the pressure exerted by the freshwater column and allowing the denser saltwater to move inland laterally.[2] In Cape May, New Jersey, since the 1940s water withdrawals have lowered groundwater levels by up to 30 meters, reducing the water table to below sea level and causing widespread intrusion and contamination of water supply wells.[5][6]

Groundwater extraction can also lead to well contamination by causing upwelling, or upcoming, of saltwater from the depths of the aquifer.[7] Under baseline conditions, a saltwater wedge extends inland, underneath the freshwater because of its higher density. Water supply wells located over or near the saltwater wedge can draw the saltwater upward, creating a saltwater cone that might reach and contaminate the well. Some aquifers are predisposed towards this type of intrusion, such as the Lower Floridan aquifer: though a relatively impermeable rock or clay layer separates fresh groundwater from saltwater, isolated cracks breach the confining layer, promoting upward movement of saltwater. Pumping of groundwater strengthens this effect by lowering the water table, reducing the downward push of freshwater.[6]

Canals and drainage networks

The construction of canals and drainage networks can lead to saltwater intrusion. Canals provide conduits for saltwater to be carried inland, as does the deepening of existing channels for navigation purposes.[2][8] In Sabine Lake Estuary in the Gulf of Mexico, large-scale waterways have allowed saltwater to move into the lake, and upstream into the rivers feeding the lake. Additionally, channel dredging in the surrounding wetlands to facilitate oil and gas drilling has caused land subsidence, further promoting inland saltwater movement.[9]

Drainage networks constructed to drain flat coastal areas can lead to intrusion by lowering the freshwater table, reducing the water pressure exerted by the freshwater column. Saltwater intrusion in southeast Florida has occurred largely as a result of drainage canals built between 1903 into the 1980s to drain the Everglades for agricultural and urban development. The main cause of intrusion was the lowering of the water table, though the canals also conveyed seawater inland until the construction of water control gates.[6]

Effect on water supply

Many coastal communities around the United States are experiencing saltwater contamination of water supply wells, and this problem has been seen for decades.[10] Many Mediterranean coastal aquifers suffer for seawater intrusion effects.[11][12] The consequences of saltwater intrusion for supply wells vary widely, depending on extent of the intrusion, the intended use of the water, and whether the salinity exceeds standards for the intended use.[2][13] In some areas such as Washington State, intrusion only reaches portions of the aquifer, affecting only certain water supply wells. Other aquifers have faced more widespread salinity contamination, significantly affecting groundwater supplies for the region. For instance, in Cape May, New Jersey, where groundwater extraction has lowered water tables by up to 30 meters, saltwater intrusion has caused closure of over 120 water supply wells since the 1940s.[6]

Ghyben–Herzberg relation

The first physical formulations of saltwater intrusion were made by Willem Badon-Ghijben in 1888 and 1889 as well as Alexander Herzberg in 1901, thus called the Ghyben–Herzberg relation.[14] They derived analytical solutions to approximate the intrusion behavior, which are based on a number of assumptions that do not hold in all field cases.

In the equation,

the thickness of the freshwater zone above sea level is represented as and that below sea level is represented as . The two thicknesses and , are related by and where is the density of freshwater and is the density of saltwater. Freshwater has a density of about 1.000 grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) at 20 °C, whereas that of seawater is about 1.025 g/cm3. The equation can be simplified to

.[2]

The Ghyben–Herzberg ratio states that, for every meter of fresh water in an unconfined aquifer above sea level, there will be forty meters of fresh water in the aquifer below sea level.

In the 20th century the vastly increased computing power available allowed the use of numerical methods (usually finite differences or finite elements) that need fewer assumptions and can be applied more generally.[15]

Modeling

Modeling of saltwater intrusion is considered difficult. Some typical difficulties that arise are:

- The possible presence of fissures and cracks and fractures in the aquifer, whose precise positions and extents are unknown but which have great influence on the development of the saltwater intrusion

- The possible presence of small scale heterogeneities in the hydraulic properties of the aquifer, which are too small to be taken into account by the model but which may also have great influence on the development of the saltwater intrusion

- The change of hydraulic properties by the saltwater intrusion. A mixture of saltwater and freshwater is often undersaturated with respect to calcium, triggering dissolution of calcium in the mixing zone and changing hydraulic properties.

- The process known as cation exchange, which slows the advance of a saltwater intrusion and also slows the retreat of a saltwater intrusion.

- The fact that saltwater intrusions are often not in equilibrium makes it harder to model. Aquifer dynamics tend to be slow and it takes the intrusion cone a long time to adapt to changes in pumping schemes, rainfall, etc. So the situation in the field can be significantly different from what would be expected based on the sea level, pumping scheme etc.

- For long-term models, the future climate change forms a large unknown but good results are possible . Model results often depend strongly on sea level and recharge rate. Both are expected to change in the future.

Mitigation and management

Saltwater is also an issue where a lock separates saltwater from freshwater (for example the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in Washington). In this case a collection basin was built from which the saltwater can be pumped back to the sea. Some of the intruding saltwater is also pumped to the fish ladder to make it more attractive to migrating fish.[16]

As groundwater salinization becomes a relevant problem, more complex initiatives should be applied from local technical and engineering solutions to rules or regulatory instruments for whole aquifers or regions.[17]

Areas of occurrence

- Benin

- Cyprus

- Bou Regreg (Morocco)

- Pakistan

- Suriname

- Tunisia

- United States

- ACF River Basin (Florida/Georgia)

- Environment of Florida

- Essex County, Massachusetts[18]

- Hiram M. Chittenden Locks (Washington)

- Hutchinson Island (Georgia)

- Lake Lanier (Georgia)

- Lake Pontchartrain (Louisiana)

- Miami River (Florida)

- Mississippi River Delta

- Oxnard Plain (California)

- San Leandro (California)

- Sonoma Creek (California)

- Western Shore of Lake Superior[19] (Minnesota)

- Mekong Delta

- Italy[11][20][21]

See also

- Groundwater

- Environmental migrant – People forced to leave their home region due to changes to their local environment

- Garald G. Parker – American hydrologist

- Inflatable rubber dam

- Peak water – Concept on the quality and availability of freshwater resources

References

- Johnson, Teddy (2007). "Battling Seawater Intrusion in the Central & West Coast Basins" (PDF). Water Replenishment District of Southern California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-08. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- Barlow, Paul M. (2003). "Ground Water in Freshwater-Saltwater Environments of the Atlantic Coast". USGS. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- "CWPtionary Saltwater Intrusion yes". LaCoast.gov. 1996. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- Johnson, Ted (2007). "Battling Seawater Intrusion in the Central & West Coast Basins" (PDF). Water Replenishment District of Southern California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-08. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- Lacombe, Pierre J. & Carleton, Glen B. (2002). "Hydrogeologic Framework, Availability of Water Supplies, and Saltwater Intrusion, Cape May County, New Jersey" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- Barlow, Paul M. & Reichard, Eric G. (2010). "Saltwater intrusion in coastal regions of North America". Hydrogeology Journal. USGS. 18 (1): 247–260. Bibcode:2010HydJ...18..247B. doi:10.1007/s10040-009-0514-3. S2CID 128870219. Retrieved 2012-12-10.

- Reilly, T.E. & Goodman, A.S. (1987). "Analysis of saltwater upconing beneath a pumping well". Journal of Hydrology. 89 (3–4): 169–204. Bibcode:1987JHyd...89..169R. doi:10.1016/0022-1694(87)90179-x.

- Good, B. J., Buchtel, J., Meffert, D.J., Radford, J., Rhinehart, W., Wilson, R. (1995). "Louisiana's Major Coastal Navigation Channels" (pdf). Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Barlow, Paul M. (2008). "Preliminary Investigation: Saltwater Barrier - Lower Sabine River" (PDF). Sabine River Authority of Texas. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

- Todd, David K. (1960). "Salt water intrusion of coastal aquifers in the United States" (PDF). Subterranean Water. IAHS Publ. (52): 452–461. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-25. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- Polemio, Maurizio (2016-04-01). "Monitoring and Management of Karstic Coastal Groundwater in a Changing Environment (Southern Italy): A Review of a Regional Experience". Water. 8 (4): 148. doi:10.3390/w8040148.

- Polemio, Maurizio; Pambuku, Arben; Limoni, Pier Paolo; Petrucci, Olga (2011-01-01). "Carbonate Coastal Aquifer of Vlora Bay and Groundwater Submarine Discharge (Southwestern Albania)". Journal of Coastal Research. 270: 26–34. doi:10.2112/SI_58_4. ISSN 0749-0208. S2CID 54861536.

- Romanazzi A, Polemio M. "Modelling of coastal karst aquifers for management support: Study of Salento (Apulia, Italy)" (PDF). Italian Journal of Engineering Geology and Environment. 13, 1: 65–83.

- Verrjuit, Arnold (1968). "A note on the Ghyben-Herzberg formula" (PDF). Bulletin of the International Association of Scientific Hydrology. Delft, Netherlands: Technological University. 13 (4): 43–46. doi:10.1080/02626666809493624. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- Romanazzi, A.; Gentile, F.; Polemio, M. (2015-07-01). "Modelling and management of a Mediterranean karstic coastal aquifer under the effects of seawater intrusion and climate change". Environmental Earth Sciences. 74 (1): 115–128. Bibcode:2015EES....74..115R. doi:10.1007/s12665-015-4423-6. ISSN 1866-6299. S2CID 56376966.

- Mausshardt, Sherrill; Singleton, Glen (1995). "Mitigating Salt-Water Intrusion through Hiram M. Chittenden Locks". Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering. 121 (4): 224–227. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(1995)121:4(224).

- Polemio, Maurizio; Zuffianò, Livia Emanuela (2020). "Review of Utilization Management of Groundwater at Risk of Salinization". Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management. 146 (9): 03120002. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0001278. ISSN 0733-9496. S2CID 225224426.

- "Case Studies of Various Water Quality Problems | H2O Care".

- "In a Pickle: The Mystery of the North Shore's Salty Well Water". www.seagrant.umn.edu. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- Vespasiano, Giovanni; Cianflone, Giuseppe; Romanazzi, Andrea; Apollaro, Carmine; Dominici, Rocco; Polemio, Maurizio; De Rosa, Rosanna (2019-11-01). "A multidisciplinary approach for sustainable management of a complex coastal plain: The case of Sibari Plain (Southern Italy)". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 109: 740–759. Bibcode:2019MarPG.109..740V. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.06.031. ISSN 0264-8172. S2CID 197580624.

- Zuffianò, L. E.; Basso, A.; Casarano, D.; Dragone, V.; Limoni, P. P.; Romanazzi, A.; Santaloia, F.; Polemio, M. (2016-07-01). "Coastal hydrogeological system of Mar Piccolo (Taranto, Italy)". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 23 (13): 12502–12514. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-4932-6. ISSN 1614-7499. PMID 26201653. S2CID 9262421.