Salvador Allende

Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens (US: /ɑːˈjɛndeɪ, -di/,[1][2] UK: /æˈ-, aɪˈɛn-/,[3] Latin American Spanish: [salβaˈðoɾ ɣiˈʝeɾmo aˈʝende ˈɣosens]; 26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a socialist politician,[4][5] who served as the 28th president of Chile from 1970 until his death in 1973.[6] As a democratic socialist committed to democracy,[7][8] he has been described as the first Marxist to be elected president in a liberal democracy in Latin America.[9][10][11]

Salvador Allende | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1970 | |

| 28th President of Chile | |

| In office 3 November 1970 – 11 September 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Eduardo Frei Montalva |

| Succeeded by | Augusto Pinochet |

| 56th President of the Senate of Chile | |

| In office 27 December 1966 – 15 May 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Tomás Reyes Vicuña |

| Succeeded by | Tomás Pablo Elorza |

| Member of the Senate | |

| In office 15 May 1969 – 3 November 1970 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Adonis Sepúlveda Acuña |

| Constituency | Chiloé, Aysén and Magallanes |

| In office 15 May 1961 – 15 May 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Carlos Alberto Martínez |

| Succeeded by | Hugo Ballesteros Reyes |

| Constituency | Aconcagua and Valparaíso |

| In office 15 May 1953 – 15 May 1961 | |

| Preceded by | Elías Lafertte Gaviño |

| Succeeded by | Raúl Ampuero Díaz |

| Constituency | Tarapacá and Antofagasta |

| In office 15 May 1945 – 15 May 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Luis Ambrosio Concha |

| Succeeded by | Aniceto Rodríguez Arenas |

| Constituency | Valdivia, Osorno, Llanquihue, Chiloé, Aysén and Magallanes |

| Secretary of the Socialist Party of Chile | |

| In office January 1943 – July 1944 | |

| Preceded by | Marmaduke Grove |

| Succeeded by | Bernardo Ibáñez |

| Minister of Health and Social Welfare | |

| In office 28 September 1939 – 2 April 1942 | |

| President | Pedro Aguirre Cerda |

| Preceded by | Miguel Etchebarne Riol |

| Succeeded by | Eduardo Escudero Forrastal |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 15 May 1937 – 28 September 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Humberto Casali Monreal |

| Succeeded by | Vasco Valdebenito García |

| Constituency | Quillota and Valparaíso |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens 26 June 1908 Santiago, Chile |

| Died | 11 September 1973 (aged 65) Santiago, Chile |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Resting place | Santiago General Cemetery |

| Political party | Socialist |

| Other political affiliations | Popular Unity Coalition |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Beatriz and Isabel |

| Relatives | Allende family |

| Alma mater | University of Chile |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Website | Foundation |

Allende's involvement in Chilean politics spanned a period of nearly forty years, during which he held various positions including senator, deputy, and cabinet minister. As a life-long committed member of the Socialist Party of Chile, whose foundation he had actively contributed to, he unsuccessfully ran for the national presidency in the 1952, 1958, and 1964 elections. In 1970, he won the presidency as the candidate of the Popular Unity coalition in a close three-way race. He was elected in a run-off by Congress, as no candidate had gained a majority. In office, Allende pursued a policy he called "The Chilean Way to Socialism". The coalition government was far from unanimous. Allende said that he was committed to democracy and represented the more moderate faction of the Socialist Party, while the radical wing sought a more radical course. Instead, the Communist Party of Chile favored a gradual and cautious approach that sought cooperation with Christian democrats,[7] which proved influential for the Italian Communist Party and the Historic Compromise.[12]

As president, Allende sought to nationalize major industries, expand education, and improve the living standards of the working class. He clashed with the right-wing parties that controlled Congress and with the judiciary. On 11 September 1973, the military moved to oust Allende in a coup d'état supported by the CIA, which initially denied the allegations.[13][14] In 2000, the CIA admitted its role in the 1970 kidnapping of a top general who had refused to use the army to stop Allende's inauguration.[15][16] 2023 declassified documents showed that US president Richard Nixon, his national security advisor Henry Kissinger, and the United States government, which had branded Allende as a dangerous communist,[8] were aware of the 1973 coup d'état and its plans to overthrow Allende's democratically-elected government.[17]

As troops surrounded La Moneda Palace, Allende gave his last speech vowing not to resign.[18] Later that day, Allende died by suicide in his office;[19][20][21] the exact circumstances of his death are still disputed.[22][upper-alpha 1] Following Allende's death, General Augusto Pinochet refused to return authority to a civilian government, and Chile was later ruled by the Government Junta, ending more than four decades of uninterrupted democratic governance, a period known as the Presidential Republic (1925–1973); the military dictatorship of Pinochet only ended after the successful internationally-backed 1989 constitutional referendum led to the peaceful Chilean transition to democracy. The military junta that took over dissolved Congress, suspended the Constitution of 1925, and initiated a program of persecuting alleged dissidents, in which at least 3,095 civilians disappeared or were killed.[24]

Early life

_(page_1_crop).jpg.webp)

Allende was born on 26 June 1908[25] in Santiago.[26][27] He was the son of Salvador Allende Castro and Laura Gossens Uribe. Allende's family belonged to the Chilean upper middle class and had a long tradition of political involvement in progressive and liberal causes. His grandfather was a prominent physician and a social reformist who founded one of the first secular schools in Chile.[28] Salvador Allende was of Basque[29] and Belgian descent.[30][31][32] In 1909 he moved with his family to the city of Tacna (then under Chilean administration), living there until 1916, since in that year he would move back to his country in the city of Iquique. In 1918 he studied at the National Institute of Santiago, and in 1919 to 1921 he studied at the Liceo de Valdivia. In 1922 he entered the Eduardo de la Barra school at the age of 16, studying there until 1924.[33]

As a teenager, his main intellectual and political influence came from the shoe-maker Juan De Marchi, an Italian-born anarchist,[28] in 1925 he attended the military service in the Cuirassier Regiment of Tacna.[33] Allende was a talented athlete in his youth, being a member of the Everton de Viña del Mar sports club (named after the more famous English football club of the same name).[34] In 1926 at the age of 18 he studied medicine at the University of Chile in Santiago and in 1927 was elected President of the Student Center. In 1928 he entered the Grand Lodge of Chile and in 1929 he was elected vice president of the Federation of Students of the University of Chile, (FECH). In 1930, he became the representative of the students of the School of Medicine.[33]

During his time at medical school Allende was influenced by Professor Max Westenhofer, a German pathologist who emphasized the social determinants of disease and social medicine.[35][36] In 1931 he was relegated to the North and expelled from the university. However, in that same year, he retook his sixth year of medical school and graduated at 23 years of age. In 1932 he began to practice his profession as a physician and anatomo-pathologist in the Morgue of the Van Buren Hospital. He became the union leader of the Valparaíso doctors, becoming 1st Regional Secretary in Valparaíso. In 1935, at the age of 27, he was relegated to the city of Caldera for the second time, and in 1936 he was imprisoned in the Popular Front in Valparaíso. In 1937 he was elected Deputy of Valparaíso and Aconcagua and in 1938 he served as Undersecretary General of the Socialist Party of Chile.[33]

In 1933 Allende co-founded with Marmaduque Grove and others a section of the Socialist Party of Chile in Valparaíso[28] and became its chairman. He married Hortensia Bussi with whom he had three daughters. He was a Freemason, a member of the Lodge Progreso No. 4 in Valparaíso.[37] In 1933, he published his doctoral thesis Higiene Mental y Delincuencia (Crime and Mental Hygiene) in which he criticized Cesare Lombroso's proposals.[38]

Political involvement up to 1970

In 1938, Allende was in charge of the electoral campaign of the Popular Front headed by Pedro Aguirre Cerda.[28] The Popular Front's slogan was "Bread, a Roof and Work!"[28] After its electoral victory, he became Minister of Health in the Reformist Popular Front government which was dominated by the Radicals.[28] While serving in that position, Allende was responsible for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms, including safety laws protecting workers in the factories, higher pensions for widows, maternity care, and free lunch programmes for schoolchildren.[39]

Upon entering the government, Allende relinquished his congressional seat for Valparaíso, which he had won in 1937. Around that time, he wrote La Realidad Médico Social de Chile (The social and medical reality of Chile). After the Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany, Allende was one of 76 members of the Congress who sent a telegram to Adolf Hitler denouncing the persecution of Jews.[40] Following President Aguirre Cerda's death in 1941, he was again elected deputy while the Popular Front was renamed Democratic Alliance.

In 1945, Allende became senator for the Valdivia, Llanquihue, Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes provinces; then for Tarapacá and Antofagasta in 1953; for Aconcagua and Valparaíso in 1961; and once more for Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes in 1969. He became president of the Chilean Senate in 1966. During the 50's Allende introduced legislation that established the Chilean national health service, the first program in the Americas to guarantee universal health care.[41]

His three unsuccessful bids for the presidency (in the 1952, 1958 and 1964 elections) prompted Allende to joke that his epitaph would be "Here lies the next President of Chile." In 1952, as candidate for the Frente de Acción Popular (Popular Action Front, FRAP), he obtained only 5.4% of the votes, partly due to a division within socialist ranks over support for Carlos Ibáñez. In 1958, again as the FRAP candidate, Allende obtained 28.5% of the vote. This time, his defeat was attributed to votes lost to the populist Antonio Zamorano.[42] This explanation has been questioned by modern research that suggest Zamorano's votes came from across the political spectrum.[42]

Electoral system

Declassified documents show that from 1962 through 1964, the CIA spent a total of $2.6 million to finance the campaign of Eduardo Frei and $3 million in anti-Allende propaganda "to scare voters away from Allende's FRAP coalition". The CIA considered its role in the victory of Frei a great success.[43][44]

They argued that "the financial and organizational assistance given to Frei, the effort to keep Durán in the race, the propaganda campaign to denigrate Allende—were 'indispensable ingredients of Frei's success'", and they thought that his chances of winning and the good progress of his campaign would have been doubtful without the covert support of the Government of the United States.[45] Thus, in 1964 Allende lost once more as the FRAP candidate, polling 38.6% of the votes against 55.6% for Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. As it became clear that the election would be a race between Allende and Frei, the political right – which initially had backed Radical Julio Durán– settled for Frei as "the lesser evil".

1970 election

_(cropped_%2526_edited).jpg.webp)

Allende was considered part of the moderate wing of the Socialists, with support from the Communists who favored taking power via parliamentary democracy; in contrast, the left-wing of the Socialists (led by Carlos Altamirano) and several other far-left parties called for violent insurrection. Some argue, however, that this was reversed at the end of his period in office.[46][upper-alpha 2]

Allende won the 1970 Chilean presidential election as leader of the Unidad Popular ("Popular Unity") coalition. On 4 September 1970, he obtained a narrow plurality of 36.61% to 35.27% over Jorge Alessandri, a former president, with 27.8% going to a third candidate (Radomiro Tomic) of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC). According to the Chilean Constitution of the time, if no presidential candidate obtained a majority of the popular vote, Congress would choose one of the two candidates with the highest number of votes as the winner. Tradition was for Congress to vote for the candidate with the highest popular vote, regardless of margin. Former president Jorge Alessandri had been elected in 1958 with a plurality of 31.56% over Allende's 28.85%.[48]

One month after the election, on 20 October, while the Senate had still to reach a decision and negotiations were actively in place between the Christian Democrats and the Popular Unity, General René Schneider, Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army, was shot resisting a kidnap attempt by a group led by General Roberto Viaux. Hospitalized, he died of his wounds three days later, on 23 October.[49] Schneider was a defender of the "constitutionalist" doctrine that the army's role is exclusively professional, its mission being to protect the country's sovereignty and not to interfere in politics.[50]

General Schneider's death was widely disapproved of and, for the time, ended military opposition to Allende,[51] whom the Congress finally chose on 24 October. On 26 October, President Eduardo Frei named General Carlos Prats as commander in chief of the army to replace René Schneider.[52] Allende assumed the Presidency on 3 November 1970 after signing a Statute of Constitutional Guarantees proposed by the Christian Democrats in return for their support in Congress. In an extensive interview with Régis Debray in 1972, Allende explained his reasons for agreeing to the guarantees.[53] Some critics have interpreted Allende's responses as an admission that signing the Statute was only a tactical move.[54]

Presidency

"The Chilean Way to Socialism"

In his speech to the Chilean legislature following his election, Allende made clear his intention to move Chile from a capitalist to a socialist society:

We are moving towards socialism, not from an academic love for a doctrinaire system, but encouraged by the strength of our people, who know that it is an inescapable demand if we are to overcome backwardness and who feel that a socialist regime is the only way available to modern nations who want to build rationally in freedom, independence and dignity. We are moving towards socialism because the people, through their vote, have freely rejected capitalism as a system which has resulted in a crudely unequal society, a society deformed by social injustice and degraded by the deterioration of the very foundations of human solidarity.[55]

Upon assuming the presidency, Allende began to carry out his platform of implementing a socialist programme called La vía chilena al socialismo ("the Chilean Path to Socialism"). That included nationalization of large-scale industries (notably copper mining and banking), and government administration of the health-care system, educational system (with the help of a United States educator, Jane A. Hobson-Gonzalez from Kokomo, Indiana), a programme of free milk for children in the schools and in the shanty towns of Chile, and an expansion of the land seizure and redistribution already begun under his predecessor Eduardo Frei Montalva,[56] who had nationalized between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the properties listed for takeover.[57] Allende also intended to improve the socio-economic welfare of Chile's poorest citizens;[58] a key element was to provide employment, either in the new nationalized enterprises or on public-work projects.[58]

In November 1970, 3,000 scholarships were allocated to Mapuche children in an effort to integrate the indigenous minority into the educational system, payment of pensions and grants was resumed, an emergency plan providing for the construction of 120,000 residential buildings was launched, all part-time workers were granted rights to social security, a proposed electricity price-increase was withdrawn, diplomatic relations were restored with Cuba, and political prisoners were granted an amnesty. In December 1970, bread prices were fixed, 55,000 volunteers were sent to the south of the country to teach writing and reading skills and to provide medical attention to a sector of the population that had previously been ignored, a central commission was established to oversee a tri-partite payment plan in which equal place was given to government, employees and employers, and a protocol agreement was signed with the United Centre of Workers which granted workers representational rights on the funding board of the Social Planning Ministry.[59]

An obligatory minimum wage for workers of all ages (including apprentices) was established,[60] free milk was introduced for expectant and nursing mothers and for children between the ages of 7 and 14,[61] free school-meals were established,[62] rent reductions were carried out, and the construction of the Santiago subway was rescheduled so as to serve working-class neighbourhoods first. Workers benefited from increases in social-security payments, an expanded public-works program, and a modification of the wage and salary adjustment mechanism (which had originally been introduced in the 1940s to cope with the country's chronic inflation), while middle-class Chileans benefited from the elimination of taxes on modest incomes and property.[63] In addition, state-sponsored programs distributed free food to the country's neediest citizens,[64] and in the countryside, peasant councils were established to mobilise agrarian workers and small proprietors. In the government's first budget (presented to the Chilean congress in November 1970), the minimum taxable income-level was raised, removing from the tax pool 35% of those who had paid taxes on earnings in the previous year. In addition, the exemption from general taxation was raised to a level equivalent to twice the minimum wage. Exemptions from capital taxes were also extended, which benefitted 330,000 small proprietors. The extra increases that Frei had promised to the armed forces were also fully paid. According to one estimate, purchasing power went up by 28% between October 1970 and July 1971.[65]

Minimum real wages and inflation

The rate of inflation fell from 36.1% in 1970 to 22.1% in 1971, while average real wages rose by 22.3% during 1971.[upper-alpha 3][66] Minimum real wages for blue-collar workers were increased by 56% during the first quarter of 1971, while in the same period real minimum wages for white-collar workers were increased by 23%, a development that decreased the differential ratio between blue- and white-collar workers' minimum wage from 49% (1970) to 35% (1971). Central government expenditures went up by 36% in real terms, raising the share of fiscal spending in GDP from 21% (1970) to 27% (1971), and as part of this expansion, the public sector engaged in a huge housing program, starting to build 76,000 houses in 1971, compared to 24,000 for 1970.[66] During a 1971 emergency program, over 89,000 houses were built, and during Allende's three years as president an average of 52,000 houses were constructed annually.[67] Although the acceleration of inflation in 1972 and 1973 eroded part of the initial increase in wages, they still rose (on average) in real terms during the 1971–73 period.[68] Additionally, Allende government had reduced inflation to 14% in the first nine months of 1971.[69]

Allende's first step in early 1971 was to raise minimum wages (in real terms) for blue-collar workers by 37%–41% and by 8%–10% for white-collar workers. Education, food, and housing assistance expanded significantly, with public housing starts going up twelvefold and eligibility for free milk extended from age 6 to age 15. A year later, blue-collar wages were raised by 27% in real terms and white-collar wages became fully indexed.[70] Price controls were also set up, while the Allende Government introduced a system of distribution networks through various agencies (including local committees on supply and prices) to ensure that shopkeepers adhered to the new rules.[71]

Agrarian and literacy reforms

The new Minister of Agriculture, Jacques Chonchol, promised to expropriate all estates which were larger than eighty "basic" hectares (about 200 acres). That promise was kept, with no farm in Chile exceeding that limit by the end of 1972.[72] Within eighteen months the Latifundia (extensive agricultural estates) had been abolished. The agrarian reform had involved the expropriation of 3,479 properties which, added to the 1,408 properties incorporated under the Frei government, made up some 40% of the total agricultural land area in the country.[65]

Particularly in rural areas, the Allende government launched a campaign against illiteracy, while adult education programs expanded, together with educational opportunities for workers. From 1971 to 1973, enrolments in kindergarten, primary, secondary, and post-secondary schools all increased. The Allende government encouraged more doctors to begin practising in rural and low-income urban areas, and built additional hospitals, maternity clinics, and especially neighborhood health-centers that remained open for longer hours to serve the poor. Improved sanitation and housing facilities for low-income neighborhoods also equalized health-care benefits, while hospital councils and local health councils were established in neighborhood health-centers as a means of democratizing the administration of health policies. The councils gave central-government civil-servants, local-government officials, health-service employees, and community workers the right to review budgetary decisions.[73]

The Allende government sought to bring the arts to the mass of the Chilean population by funding a number of cultural endeavours. With eighteen-year-olds and illiterates now granted the right to vote, mass participation in decision-making was encouraged by the Allende government, with traditional hierarchical structures now challenged by socialist egalitarianism. The Allende Government was able to draw upon the idealism of its supporters, with teams of "Allendistas" travelling into the countryside and shanty towns to perform volunteer work.[72] The Allende government also worked to transform Chilean popular culture through formal changes to school curriculum and through broader cultural education initiatives, such as state-sponsored music festivals and tours of Chilean folklorists and nueva canción musicians.[74] In 1971, the purchase of a private publishing house by the state gave rise to Editorial Quimantu, which became the center of the Allende Government's cultural activities. In the space of two years, 12 million copies of books, magazines, and documents (8 million of which were books) specializing in social analysis, were published. Cheap editions of great literary works were produced on a weekly basis, and in most cases were sold out within a day. Culture came into the reach of the masses for the first time, who responded enthusiastically. "Editorial Quimantu" encouraged the establishment of libraries in community organizations and trade unions. Through the supply of cheap textbooks, it enabled the Left to progress through the ideological content of the literature made available to workers.[65]

To improve social and economic conditions for women, the Women's Secretariat was established in 1971, which took on issues such as public laundry facilities, public food programs, day-care centers, and women's health care (especially prenatal care).[75] The duration of maternity leave was extended from 6 to 12 weeks,[76] while the Allende Government steered the educational system towards poorer Chileans by expanding enrollments through government subsidies.[77] A "democratisation" of university education was carried out, making the system tuition-free, which led to an 89% rise in university enrollments between 1970 and 1973. The Allende Government also increased enrollment in secondary education from 38% in 1970 to 51% in 1974.[78] Enrollment in education reached record levels, including 3.6 million young people, and 8 million school textbooks were distributed among 2.6 million pupils in primary education. An unprecedented 130,000 students were enrolled by the universities, which became accessible to peasants and workers. The illiteracy rate was reduced from 12% in 1970 to 10.8% in 1972, while the growth in primary school enrollment increased from an annual average of 3.4% in the period 1966–70 to 6.5% in 1971–1972. Secondary education grew at a rate of 18.2% in 1971–1972, and the average school enrollment of children between the ages of 6 and 14 rose from 91% (1966–70) to 99%.[65]

Social welfare and programs

Social spending was dramatically increased, particularly for housing, education, and health, and a major effort was made to redistribute wealth to poorer Chileans. As a result of new initiatives in nutrition and health, together with higher wages, many poorer Chileans were able to feed and clothe themselves better than ever before. Public access to the social security system was increased, and state benefits such as family allowances were raised significantly.[72] The redistribution of income enabled wage and salary earners to increase their share of national income from 51.6% (the annual average between 1965 and 1970) to 65% while family consumption increased by 12.9% in the first year of the Allende Government. In addition, while the average annual increase in personal spending had been 4.8% in the period 1965–70, it reached 11.9% in 1971.[65] During the first two years of Allende's presidency, state expenditure on health rose from around 2% to nearly 3.5% of GDP. According to Jennifer E. Pribble, the new spending "was reflected not only in public health campaigns, but also in the construction of health infrastructure".[79] Small programs targeted at women were also experimented with, such as cooperative laundries and communal food preparation, together with an expansion of child-care facilities.[80]

The National Supplementary Food Program was extended to all primary school pupils and to all pregnant women, regardless of their employment or income condition. Complementary nutritional schemes were applied to malnourished children, while antenatal care was emphasized.[81] Under Allende, the proportion of children under the age of 6 with some form of malnutrition fell by 17%.[61] Apart from the existing Supply and Prices councils (community-based bodies which controlled the distribution of essential groups in working-class districts, and were a popular, not government, initiative),[82] community-based distribution centers and shops were developed, which sold directly in working-class neighborhoods. The Allende government felt obliged to increase its intervention in marketing activities, and state involvement in grocery distribution reached 33%.[65] The CUT (central labor confederation) was accorded legal recognition,[83] and its membership grew from 700,000 to almost 1 million. In enterprises in the Area of Social Ownership, an assembly of the workers elected half of the members of the management council for each company. Those bodies replaced the former board of directors.[65]

Minimum pensions were increased by amounts equal to two or three times the inflation rate, and between 1970 and 1972, such pensions increased by a total of 550%. The incomes of 300,000 retirement pensioners were increased by the government from one-third of the minimum salary to the full amount. Labor insurance cover was extended to 200,000 market traders, 130,000 small shop proprietors, 30,000 small industrialists, small owners, transport workers, clergy, professional sportsmen, and artisans. The public health service was improved, with the establishment of a system of clinics in working-class neighborhoods on the peripheries of the major cities, providing a health center for every 40,000 inhabitants. Statistics for construction in general, and housebuilding in particular, reached some of the highest levels in the history of Chile. Four million square metres were completed in 1971–72, compared to an annual average of 2+1⁄2 million between 1965 and 1970. Workers were able to acquire goods which had previously been beyond their reach, such as heaters, refrigerators, and television sets. As further noted by Ricardo Israel Zipper, "By now meat was no longer a luxury, and the children of working people were adequately supplied with shoes and clothing. The popular living standards were improved in terms of the employment situation, social services, consumption levels, and income distribution."[65]

Economic policy

Chilean presidents were allowed a maximum term of six years, which may explain Allende's haste to restructure the economy. Not only was a major restructuring program organized (the Vuskovic plan), he also had to make it a success if a left-wing successor to Allende was going to be elected. In the first year of Allende's term, the short-term economic results of the economy minister Pedro Vuskovic's expansive monetary policy were highly favorable: 12% industrial growth and an 8.6% increase in GDP, accompanied by major declines in inflation (down from 34.9% to 22.1%) and unemployment (down to 3.8%). By 1972, the Chilean escudo had an inflation rate of 140%. The average real GDP contracted between 1971 and 1973 at an annual rate of a 5.6% negative growth, and the government's fiscal deficit soared while foreign reserves declined.[85] Unemployment rates had dropped from 6.3% in 1970 to 3.5% in 1972 before dropping again in 1973 to the lowest ever recorded.[86]

The combination of inflation and price controls, together with the disappearance of basic commodities from supermarket shelves, led to the rise of black markets in rice, beans, sugar, and flour.[87] The Chilean economic situation was also somewhat exacerbated due to a US-backed campaign to fund worker strikes in certain sectors of the economy.[88] The Allende government announced it would default on debts owed to international creditors and foreign governments. Allende also froze all prices while raising salaries. His implementation of the policies was strongly opposed by landowners, employers, businessmen and transporters associations, and some civil servants and professional unions. The rightist opposition was led by the National Party, the Roman Catholic Church (which in 1973 was displeased with the direction of educational policy),[89] and eventually the Christian Democrats. There were growing tensions with foreign multinational corporations and the government of the United States.

Allende undertook the pioneeristic Project Cybersyn, a distributed decision support system for decentralized economic planning, developed by British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer. Based on the experimental viable system model and the neural network approach to organizational design, the Project consisted of four modules: a network of telex machines (Cybernet) in all state-run enterprises that would transmit and receive information with the government in Santiago. Information from the field would be fed into statistical modeling software (Cyberstride) that would monitor production indicators, such as raw material supplies or high rates of worker absenteeism, in "almost" real time, alerting the workers in the first case and, in abnormal situations, if those parameters fell outside acceptable ranges by a very large degree, also the central government. The information would also be input into an economic simulation software (CHECO, for CHilean ECOnomic simulator) which featured a Bayesian filtering and control setting that the government could use to forecast the possible outcome of economic decisions. Finally, a sophisticated operations room (Opsroom) would provide a space where managers could see relevant economic data, formulate feasible responses to emergencies, and transmit advice and directives to enterprises and factories in alarm situations by using the telex network.[90] In conjunction with the system, the Cybersyn development team also planned the Cyberfolk device system, a closed television circuit connected to an interactive apparatus that would enable the citizenry to actively participate in economic and political decision-making.

Allende raised wages on a number of occasions throughout 1970 and 1971, but the wage hikes were negated by ongoing inflation of Chile's fiat currency. Although price rises had been high even under Frei (27% a year between 1967 and 1970), a basic basket of consumer goods rose by 120% from 190 to 421 escudos in one month alone, August 1972. From 1970 to 1972, while Allende was in government, exports fell 24% and imports rose 26%, with imports of food rising an estimated 149%.[91] Export income fell due to a hard-hit copper industry; the price of copper on international markets fell by almost a third, and post-nationalization copper production fell as well. Copper is Chile's single most important export, as more than half of Chile's export receipts were from that sole commodity.[92] The price of copper fell from a peak of $66 per ton in 1970 to only $48–49 in 1971 and 1972.[93] Chile was already dependent on food imports, and the decline in export earnings coincided with declines in domestic food production following Allende's agrarian reforms.[94]

Foreign policy

In 1971, Chile re-established diplomatic relations with Cuba, joining Mexico and Canada in rejecting a previously established Organization of American States convention prohibiting governments in the Western Hemisphere from establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba. Shortly afterward, Cuban president Fidel Castro made a month-long visit to Chile. Originally, the visit was supposed to be one week; however, Castro enjoyed Chile and one week led to another. Despite his attitude of socialist solidarity, Castro was reportedly critical of Allende's policies. Castro was quoted as saying that "Marxism is a revolution of production", whereas "Allende's was a revolution of consumption."[95]

Socioeconomic and political tensions

In October 1972, the first of what were to be a wave of strikes was led first by truckers, and later by small businessmen, some (mostly professional) unions and some student groups. Other than the inevitable damage to the economy, the chief effect of the 24-day strike was to induce Allende to bring the head of the army, general Carlos Prats, into the government as Interior Minister.[87] Allende also instructed the government to commandeer trucks to keep the nation from coming to a halt. Government supporters also helped to mobilize trucks and buses, but violence served as a deterrent to full mobilization, even with police protection for the strike-breakers. Allende's actions were eventually declared unlawful by the Chilean appeals court and the government was ordered to return trucks to their owners.[96] Throughout his presidency, racial tensions between the poor descendants of indigenous people, who supported Allende's reforms, and the white elite increased.[97]

Throughout his presidency, Allende remained at odds with the Chilean Congress, which was dominated by the Christian Democratic Party. In 1964, Eduardo Frei had promised a "Revolution in Liberty", a middle-class revolution that was funded by the United States government's Alliance for Progress.[98] Frei carried out a series of progressive reforms, including land reform, an issue that had not been touched since Chile's independence in the early 19th century. According to historian Marian Schlotterbeck, this was "[John F.] Kennedy's vision — stave off the threat of communist revolution by improving standards of living across the continent".[99] The Christian Democrats had campaigned on a socialist platform in the 1970 elections but drifted away from those positions during Allende's presidency, and accused Allende of leading Chile toward a Cuban-style dictatorship and sought to overturn many of his more radical policies. They eventually formed a coalition with the National Party.[100]

Allende and his opponents in Congress repeatedly accused each other of undermining the Chilean Constitution and acting undemocratically. Allende's increasingly bold socialist policies (partly in response to pressure from some of the more radical members within his coalition), combined with his close contacts with Cuba, heightened fears in Washington. The Nixon administration continued exerting economic pressure on Chile via multilateral organizations and continued to back Allende's opponents in the Chilean Congress. Almost immediately after his election, Nixon directed CIA and US State Department officials to "put pressure" on the Allende government.[101] His economic policies were used by economists Rudi Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards to coin the term macroeconomic populism.[102] In 1972, Chile's inflation stood at 150%.[103]

Foreign relations during Allende's presidency

Salvador Allende took office in a difficult international context. Chile was aligned with the United States in 1970. Elsewhere in Latin America, Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia were ruled by conservative military dictatorships (soon to be joined by Uruguay). Colombia and Venezuela also had conservative, but democratically elected, governments. Only Cuba, Peru and Mexico viewed the Chilean socialist experiment with sympathy. Under Allende's presidency, Chile joined the Non-Aligned Movement, a position that was then almost unique in Latin America.[104]

Chile, which until then had been fussy about ideological boundaries, diversified its diplomatic and trade relations, regardless of the internal political regime of each country. The government established diplomatic relations with two Latin American countries (Cuba and Guyana), seven African countries (Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Madagascar, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zaire), three European countries (Albania, East Germany and Hungary) and seven Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, North Korea, China, Mongolia, South Vietnam and North Vietnam).[104]

It tried to promote Latin American integration. At the 1971 Latin American Economic and Social Council, the Chilean representative Gonzalo Martner García formulated four major proposals, summarized by the historian Jorge Magasich: "1) to ask the United States for a moratorium on external debt for a decade in order to allocate these sums to development policies; 2) to create a Latin American central bank to "invest Latin America's reserves, 70% of which are in the United States", to receive "the region's deposits and assets" and to coordinate the operations of the central banks in order to protect the region from financial turbulence; 3) Promote the creation of a global technology fund for development, fed by compulsory contributions of licenses, industrial processes and other funds for research, so as to limit the abuses associated with technological property; 4) Create a Latin American organisation for the development of science and technology appropriate to the region."[104]

He began negotiations with Bolivia over the historical dispute between the two countries (the latter having lost access to the sea since the War of the Pacific between 1879 and 1884) and welcomed Bolivia's maritime request. Nevertheless, relations became tense again following a coup d'état by Bolivian General Hugo Banzer in August 1971. At the same time, Chile granted asylum to thousands of political exiles from Latin American countries.[104]

Salvador Allende openly rejected the influence of the Organization of American States (OAS), a body close to the United States government, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which favored the interests of more developed countries. On the other hand, he was a fervent defender of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which he considered to be more representative since it allowed economic and trade issues to be negotiated on an equal legal footing. In a speech to UNCTAD, he also warned of the policy of the United States, Japan and the European Economic Community to progressively eliminate obstacles to free trade. He said that "freeing up trade ... erases at a stroke the benefits that the Generalised System of Preferences brings to developing countries".[104]

Allende's Popular Unity government tried to maintain normal relations with the United States. When Chile nationalized its copper industry, the United States government cut off support and increased its support to opposition. Forced to seek alternative sources of trade and finance, Chile gained commitments from the Soviet Union to invest some $400 million in Chile in the next six years. The United States Departement of State put it at $115 million from Eastern Europe and $65 million from China, while Soviet and Chilean Popular Unity sources put it at total of $620 million from socialist countries. Much of the credit was never utilized, and the Soviet were not willing to subsidize Chile the same way they did for Cuba.[105]

Allende's government was disappointed that it received far less economic assistance from the Soviets than it hoped for. Trade between the two countries did not significantly increase and the credits were mainly linked to the purchase of Soviet equipment. Moreover, credits from the Soviet Union were much less than those provided to the People's Republic of China and countries of the Eastern Bloc. When Allende visited the Soviet Union in late 1972 in search of more aid and additional lines of credit after three years, he was turned down.[106]

United States involvement

The United States opposition to Allende started several years before he was elected President of Chile. Declassified documents show that from 1962 to 1964, the CIA spent $3 million on anti-Allende propaganda "to scare voters away from Allende's FRAP coalition" and spent a total of $2.6 million to finance the presidential campaign of Eduardo Frei.[43][44]

The possibility of Allende winning Chile's 1970 election was deemed a disaster by the Nixon administration that wanted to protect American geopolitical interests by preventing the spread of Communism during the Cold War.[107] In September 1970, then United States president Richard Nixon informed the CIA that an Allende government in Chile would not be acceptable and authorized $10 million to stop Allende from coming to power or unseat him.[108] A CIA document declared, "It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup."[109] Henry Kissinger's 40 Committee and the CIA planned to impede Allende's investiture as President of Chile with covert efforts known as "Track I" and "Track II"; Track I sought to prevent Allende from assuming power via so-called "parliamentary trickery", while under the Track II initiative, the CIA tried to convince key Chilean military officers to carry out a coup.[108]

Some point to the involvement of the Defense Intelligence Agency agents that allegedly secured the missiles used to bombard La Moneda Palace.[110] In fact, open US military aid to Chile continued during the Allende administration, and the national government was very much aware of that although there is no record that Allende himself believed that such assistance was anything but beneficial to Chile. During Richard Nixon's presidency, United States officials attempted to prevent Allende's election by financing political parties aligned with opposition candidate Jorge Alessandri and supporting strikes in the mining and transportation sectors.[111] After the 1970 election, the Track I operation attempted to incite Chile's outgoing president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, to persuade his party (PDC) to vote in Congress for Alessandri.[112]

Under the plan, Alessandri would resign his office immediately after assuming it and call new elections. Eduardo Frei would then be constitutionally able to run again (since the Chilean Constitution did not allow a president to hold two consecutive terms, but allowed multiple non-consecutive ones), and presumably easily defeat Allende. The Chilean Congress instead chose Allende as president, on the condition that he would sign a "Statute of Constitutional Guarantees" affirming that he would respect and obey the Chilean Constitution and that his reforms would not undermine any of its elements. Track II was aborted, as parallel initiatives already underway within the Chilean military rendered it moot.[113] During the second term of office of Democratic President Bill Clinton, the CIA acknowledged having played a role in Chilean politics before the coup, but its degree of involvement is debated. The CIA was notified by its Chilean contacts of the impending coup two days in advance but contends it "played no direct role in" the coup.[114]

Much of the internal opposition to Allende's policies came from the business sector, and recently released United States government documents confirm that the United States indirectly[88] funded the truck drivers' strike,[115] which exacerbated the already chaotic economic situation before the coup. The most prominent United States corporations in Chile before Allende's presidency were the Anaconda and Kennecott copper companies and ITT Corporation, International Telephone and Telegraph. Both copper corporations aimed to expand privatized copper production in the city of Sewell in the Chilean Andes, where the world's largest underground copper mine "El Teniente", was located.[116]

At the end of 1968, according to United States Department of Commerce data, United States corporate holdings in Chile amounted to $964 million. Anaconda and Kennecott accounted for 28% of United States holdings, but ITT had by far the largest holding of any single corporation, with an investment of $200 million in Chile.[116] In 1970, before Allende was elected, ITT owned 70% of Chitelco, the Chilean Telephone Company and funded El Mercurio, a Chilean right-wing newspaper. Documents released in 2000 by the CIA confirmed that before the elections of 1970, ITT gave $700,000 to Allende's conservative opponent, Jorge Alessandri, with help from the CIA on how to channel the money safely. ITT president Harold Geneen also offered $1 million to the CIA to help defeat Allende in the elections.[117]

After General Augusto Pinochet assumed power, United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told President Nixon that the United States "didn't do it" (referring to the coup) but "we helped them... created the conditions as great as possible".[118] Recent documents declassified under the Clinton administration's Chile Declassification Project show that the United States government and the CIA sought to overthrow Allende in 1970 immediately before he took office ("Project FUBELT"). Many documents regarding the United States intervention in Chile remain classified. Those who have been declassified showed that Nixon, Kissinger, and the United States government were aware of the coup and the plans to overthrow Allende's democratically elected government.[119][120]

Relations with the Soviet Union

Political and moral support came mostly through the Communist Party and unions of the Soviet Union. For instance, Allende received the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union in 1972. At the same time, there were some fundamental differences between Allende and Soviet political analysts, who believed that some violence or measures that those analysts "theoretically considered to be just", should have been used.[121] Declarations from KGB General Nikolai Leonov, former Deputy Chief of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, confirmed that the Soviet Union supported Allende's government economically, politically and militarily.[121] Leonov stated in an interview at the Chilean Center of Public Studies (CEP) that the Soviet economic support included over $100 million in credit, three fishing ships (that distributed 17,000 tons of frozen fish to the population), factories (as help after the 1971 earthquake), 3,100 tractors, 74,000 tons of wheat and more than a million tins of condensed milk.[121] In mid-1973, the Soviets approved the delivery of weapons (artillery and tanks) to the Chilean Army. When news of an attempt from the Army to depose Allende through a coup d'état reached Soviet officials, the shipment was redirected to another country.[121]

Allende is mentioned in a book written by the official historian of the British Intelligence MI5, Christopher Andrew.[122] According to SIS and Andrew, the book is based on the handwritten notes of KGB archivist defector Vasili Mitrokhin.[123] Andrew alleged that the KGB said that Allende "was made to understand the necessity of reorganizing Chile's army and intelligence services, and of setting up a relationship between Chile's and the USSR's intelligence services."[124] The Soviets observed closely whether the alternative form of socialism could work, and they did not interfere with the Chileans' decisions. Nikolai Leonov affirmed that whenever he tried to give advice to Latin American leaders, he was usually turned down by them, and he was told that they had their own understanding on how to conduct political business in their countries. Leonov added that the relationships of KGB agents with Latin American leaders did not involve intelligence because their intelligence target was the United States. Since many North Americans were living in the region, the Soviets were focusing in recruiting agents from the United States. Latin America was also a better region for KGB agents to get in touch with their informants from the CIA or other contacts from the United States than inside that country.[121]

Crisis

On 29 June 1973, Colonel Roberto Souper surrounded the presidential palace, La Moneda, with his tank regiment but failed to depose the government.[125] That failed coup d'état – known as the Tanquetazo ("tank putsch") – organised by the nationalist Patria y Libertad paramilitary group, was followed by a general strike at the end of July that included the copper miners of El Teniente.

In August 1973, a constitutional crisis occurred, and the Supreme Court of Chile publicly complained about the inability of the Allende government to enforce the law of the land. On 22 August, the Chamber of Deputies (with the Christian Democrats uniting with the National Party) accused the government of unconstitutional acts through Allende's refusal to promulgate constitutional amendments, already approved by the Chamber, which would have prevented his government from continuing his massive nationalization plan[126] and called upon the military to enforce constitutional order.[127]

For months, Allende had feared calling upon the Carabineros ("Carabineers", the national police force), suspecting them of disloyalty to his government. On 9 August, President Allende appointed General Carlos Prats as Minister of Defence. On 24 August 1973, General Prats was forced to resign both as defense minister and as the commander-in-chief of the army, embarrassed by both the Alejandrina Cox incident and a public protest in front of his house by the wives of his generals. General Augusto Pinochet replaced him as Army commander-in-chief the same day.[127]

Resolution by the Chamber of Deputies

On 22 August 1973, the Christian Democrats and the National Party members of the Chamber of Deputies joined to vote 81 to 47 in favor of a resolution that made accusation of disregard by the government of the separation of powers and arrogating legislative and judicial prerogatives to the executive branch of government, among other alleged constitutional violations.[128] The resolution asked the authorities to "put an immediate end" to "breach[es of] the Constitution ... with the goal of redirecting government activity toward the path of law and ensuring the Constitutional order of our Nation, and the essential underpinnings of democratic co-existence among Chileans."[129] The resolution declared that Allende's government sought "to conquer absolute power with the obvious purpose of subjecting all citizens to the strictest political and economic control by the state ... [with] the goal of establishing ... a totalitarian system" and claimed that the government had made "violations of the Constitution ... a permanent system of conduct".[129]

Specifically, the government of Allende was accused of ruling by decree and thwarting the normal legislative system, refusing to enforce judicial decisions against its partisans; not carrying out sentences and judicial resolutions that contravened its objectives, ignoring the decrees of the independent General Comptroller's Office, sundry media offenses and usurping control of the National Television Network and applying economic pressure against those media organizations that are not unconditional supporters of the government, allowing its supporters to assemble with arms, and preventing the same by its right-wing opponents, supporting more than 1,500 illegal takeovers of farms, illegal repression of the El Teniente miners' strike, and illegally limiting emigration.[129] Finally, the resolution condemned the creation and development of government-protected socialist armed groups, which were said to be "headed towards a confrontation with the armed forces". President Allende's efforts to re-organize the military and the police forces were characterized as "notorious attempts to use the armed and police forces for partisan ends, destroy their institutional hierarchy, and politically infiltrate their ranks".[129]

Allende's response

The resolution was later used by Pinochet a way to justify the coup, which occurred two weeks later.[130] On 24 August 1973, two days after the resolution, Allende responded. He accused the opposition of trying to incite a military coup by encouraging the armed forces to disobey civilian authorities.[131] He described the Congress's declaration as "destined to damage the country's prestige abroad and create internal confusion", and predicted: "It will facilitate the seditious intention of certain sectors." He observed that the declaration (passed 81–47 in the Chamber of Deputies) had not obtained the two-thirds Senate majority "constitutionally required" to convict the president of abuse of power, thus the Congress was "invoking the intervention of the armed forces and of Order against a democratically-elected government" and "subordinat[ing] political representation of national sovereignty to the armed institutions, which neither can nor ought to assume either political functions or the representation of the popular will."[132]

Allende argued that he had obeyed constitutional means for including military men to the cabinet at the service of civic peace and national security, defending republican institutions against insurrection and terrorism. In contrast, he said that Congress was promoting a coup d’état or a civil war with a declaration full of affirmations that had already been refuted beforehand and which in substance and process (directly handing it to the ministers rather than directly handing it to the president) violated a dozen articles of the then-current constitution. He further argued that the legislature was usurping the government's executive function.[132]

Allende wrote: "Chilean democracy is a conquest by all of the people. It is neither the work nor the gift of the exploiting classes, and it will be defended by those who, with sacrifices accumulated over generations, have imposed it ... With a tranquil conscience ... I sustain that never before has Chile had a more democratic government than that over which I have the honor to preside ... I solemnly reiterate my decision to develop democracy and a state of law to their ultimate consequences...Congress has made itself a bastion against the transformations ... and has done everything it can to perturb the functioning of the finances and of the institutions, sterilizing all creative initiatives." Adding that economic and political means would be needed to relieve the country's current crisis, and that the Congress was obstructing said means; having already paralyzed the state, they sought to destroy it. He concluded by calling upon the workers and all democrats and patriots to join him in defending the Chilean constitution and the revolutionary process.[132]

Coup

In early September 1973, Allende floated the idea of resolving the constitutional crisis with a plebiscite.[upper-alpha 4] His speech outlining such a solution was scheduled for 11 September but was never able to deliver it. On that same day, the Chilean military under Pinochet, aided by the United States and its CIA, staged a coup against Allende,[134] who was at the head of the first democratically elected Marxist government in Latin America.[135] Historian Peter Winn described the 1973 coup as one of the most violent events in Chilean history.[136] It led to a series of human rights abuses in Chile under Pinochet, who initiated a brutal and long-lasting campaign of political suppression through torture, murder, and exile, which significantly weakened leftist opposition to the military dictatorship of Chile (1973–1990).[137][138] Due to the coup's occurrence on the same date as the 11 September attacks in the United States, it has sometimes been referred to as "the other 9/11".[139][140][141]

Death

| "Workers of my country, I have faith in Chile and its destiny. Other men will overcome this dark and bitter moment when treason seeks to prevail. Keep in mind that, much sooner than later, the great avenues will again be opened through which will pass free men to construct a better society. Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers!" |

| —President Allende's farewell speech, 11 September 1973.[18] |

Just before the capture of La Moneda (the Presidential Palace), with gunfire and explosions clearly audible in the background, Allende gave his farewell speech to Chileans on live radio, speaking of himself in the past tense, of his love for Chile and of his deep faith in its future. He stated that his commitment to Chile did not allow him to take an easy way out, and he would not be used as a propaganda tool by those he called "traitors" (he refused an offer of safe passage).[142] Juan Seoane, Chief of President Allende's Bodyguard at the time of the events –and who was with Allende until moments previous to his death– declared in an interview reported by the University of Chile:[143]

"Allende began to say goodbye to us one by one, he gave us a hug and told us ‘Thank you for everything, comrade, thank you for everything'”, and then he said that he was going to leave last. He walked to the end of the line with his AK, turned around behind a wall, and then he shouted, 'Allende doesn't surrender…!'. The shot was heard as fifteen meters from where we were". (Reports in El Tiempo and other Latin-American media confirmed Allende´s last words).[144]

Shortly afterwards, the coup plotters announced that Allende had committed suicide. An official announcement declared that the weapon he had used was an automatic rifle. Before his death he had been photographed several times holding an AK-47, a gift from Fidel Castro.[145] He was found dead with that gun, according to contemporaneous statements made by officials in the Pinochet regime. In an interview with David Frost, Allende's first cousin, Isabel Allende, said that, at a family lunch nine days before his death, Allende had said that he would either stay till the end of this term of presidency or he would be taken out feet first.[146] Lingering doubts regarding the manner of Allende's death persisted throughout the period of the Pinochet regime. Many Chileans and independent observers refused to accept on faith the government's version of events amid speculation that Allende had been murdered by government agents. Pinochet had long left power and died when in 2011 a Chilean court opened a criminal investigation into the circumstances of Allende's death.[147][148]

The ongoing criminal investigation led to a May 2011 court order that Allende's remains be exhumed and autopsied by an international team of experts.[149] Results of the autopsy were officially released in mid-July 2011. The team of experts concluded that the former president had shot himself with an AK-47 assault rifle.[150] In December 2011 the judge in charge of the investigation affirmed the experts' findings and ruled Allende's death a suicide.[151] On 11 September 2012, the 39th anniversary of Allende's death, a Chilean appeals court unanimously upheld the trial court's ruling, officially closing the case.[152] The Guardian reported that a scientific autopsy of the remains had confirmed that "Salvador Allende committed suicide during the 1973 coup that toppled his socialist government."[149] It went on to say:

British ballistics expert David Prayer said Allende died of two shots fired from an assault rifle that was held between his legs and under his chin and was set to fire automatically. The bullets blew out the top of his head and killed him instantly. The forensics team's conclusion was unanimous. Spanish expert Francisco Etxeberria said: "We have absolutely no doubt" that Allende committed suicide.[149]

Isabel Allende Bussi, the daughter of Allende and a member of the Senate of Chile told the BBC that: "The report conclusions are consistent with what we already believed. When faced with extreme circumstances, he made the decision of taking his own life, instead of being humiliated."[153] The definitive and unanimous results produced by the 2011 Chilean judicial investigation appear to have laid to rest decades of nagging suspicions that Allende might have been assassinated by the Chilean Armed Forces. Public acceptance of the suicide theory had already been growing for much of the previous decade. In a post-junta Chile where restrictions on free speech were steadily eroding, independent and seemingly reliable witnesses began to tell their stories to the news media and to human rights researchers. The cumulative weight of the facts reported by those witnesses provided enough support for many previously unconfirmed details relating to Allende's death.[154]

Family

Well-known relatives of Salvador Allende include his daughter Isabel Allende Bussi (a politician) and his cousin Isabel Allende Llona (a writer).

Memorials

On the 30th anniversary of his death, an Allende Museum opened in Chile, and an Allende foundation has since managed his estate.[155]

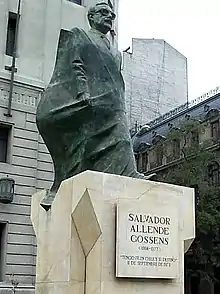

South America

Memorials to Allende include a statue in front of the Palacio de la Moneda. The placement of the statue was controversial; it was placed facing the eastern edge of the Plaza de la Ciudadanía, a plaza which contains memorials to a number of Chilean statesmen. However, the statue is not located in the plaza, but rather on a surrounding sidewalk facing an entrance to the plaza. His tomb is a major tourist attraction. Allende is buried in the general cemetery of Santiago.[156]

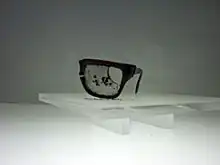

There is a square in São Paulo, Brazil, named after Allende. In Nicaragua, the tourist port of Managua is named after him. The Salvador Allende Port is located near downtown Managua. The broken glasses of Allende were given to the Chilean National History Museum in 1996 by a woman who had found them in La Moneda in 1973.[157]

Europe

In 1984, a memorial stone dedicated to him was erected in the Gajnice neighbourhood of Zagreb.[158] There is a bronze bust of him accompanied by a memorial stone in the Donaupark in Vienna.[159][160] In Istanbul, a statue of Allende can be found side by side with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Ataşehir.[161]

European landmarks named after Allende include one of the major streets in the Karaburma neighborhood of Belgrade, an avenue linking the parishes of Caxias and Paço de Arcos in Oeiras, Portugal, a park in La Spezia, Italy, and a street in Sokol District, Moscow, which named after Allende soon after his death. A memorial plaque is also installed there. Further tributes include Salvador Allende Square in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, near the Chilean embassy, the Plaza de Salvador Allende square in Viladecans, near Barcelona, and the Salvador-Allende-Straße avenue and a nearby bridge in Berlin,[162] Streets in several other German cities, especially in former East Germany but also in the West, are named after Allende, as is a street in Szekszárd, Hungary, and Allende Park in Budapest.[163] Allende Avenue (5th Avenue) in Harlow, Essex, was renamed to Zelenskyy Avenue in May 2023 in recognition of the president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[164][165]

North America

In 2009, the Salvador Allende Monument, Montreal, was installed in Parc Jean-Drapeau. A residential street in Toronto has also been named after him.[166]

Public perception

Allende is seen as a significant historical figure in Chile. The former social-democratic president Ricardo Lagos honored Allende as a humanist and a statesman.[155]

Notes

- The precise matter of Allende's death is a subject of controversy. After decades of suspicions that Allende might have been assassinated by the Chilean Armed Forces, a Chilean court in 2011 authorized the exhumation and autopsy of Allende's remains. A team of international experts examined the remains and concluded that Allende had shot himself with an AK-47 assault rifle.[23]

- The Communist Party belonged to the moderate wing of the Unidad Popular coalition, while Allende's Socialist Party was split between two factions; the moderate vía pacífica and the radical vía insurreccional.[47]

- Quote from p. 195 – "Looking at the traditional macroeconomic variables, the first year of the UP Government achieved relatively spectacular results for the Chilean economy (see tables 7.7 and 7.8)".

- Allende's personal adviser, Juan Garcés, escaped the siege on the Moneda Palace and fled to Europe, where he published testimonies about the last days of the administration: "On September 10, Allende had assembled his ministers in an extraordinary council to finalize the call announcing the plebiscite."[133]

References

Citations

- "Allende". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Allende Gossens". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Allende, Isabel". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Patsouras, Louis (2005). Marx in Context. iUniverse. p. 265.

In Chile, where a large socialist movement was in place for decades, a socialist, Salvadore Allende, led a popular front electoral coalition, including Communists, to victory in 1970.

- Medina, Eden (2014). Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile. MIT Press. p. 39.

... in Allende's socialism.

- "Profile of Salvador Allende". BBC. 8 September 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

Chile's Salvador Allende was murdered in a United States-backed coup on 11 September 1973 — three years earlier he had become Latin America's first democratically-elected Marxist president.

- Cohen, Youssef (1994). Radicals, Reformers, and Reactionaries: The Prisoner's Dilemma and the Collapse of Democracy in Latin America. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 98–118. ISBN 978-0-2261-1271-8. Retrieved 30 August 2023 – via Google Books.

- Busky, Donald F. (2000). Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-275-96886-1. Retrieved 30 August 2023 – via Google Books.

- "Chile: The Bloody End of a Marxist Dream". Time. 24 September 1973. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

Allende's downfall had implications that reached far beyond the borders of Chile. His had been the first democratically elected Marxist government in Latin America.

- Mabry, Don (2003). "Chile: Allende's Rise and Fall". Historical Text Archive. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Ross, Jen (12 December 2006). "Controversial legacy of former Chilean dictator". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

Gen. Augusto Pinochet, who overthrew Chile's democratically elected Communist government in a 1973 coup and ruled for 17 years, died Sunday without ever having been condemned for the human rights abuses committed during his rule.

- Ayala, Fernando (31 October 2020). "Salvador Allende and the Chilean way to socialism". Meer. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- "Chile: The Bloody End of a Marxist Dream". Time. 24 September 1973. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014. 24 September 1973. "Allende's downfall had implications that reached far beyond the borders of Chile. His had been the first democratically elected Marxist government in Latin America. ... Recently, TIME Correspondent Rudolph Rauch visited a group of truckers camped near Santiago who were enjoying a lavish communal meal of steak, vegetables, wine and empanadas (meat pies). 'Where does the money for that come from?' he inquired. 'From the CIA,' the truckers answered laughingly. In Washington, the CIA denied the allegation."

- Winn, Peter (2010). "Furies of the Andes". In Grandin & Joseph, Greg & Gilbert (ed.). A Century of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 239–275.

- Briscoe, David (20 September 2000). "CIA Admits Involvement in Chile". ABC News. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Evans, Michael (10 August 2023). "National Security Archive: Chile's Coup at 50: Kissinger Briefed Nixon on Failed 1970 CIA Plot to Block Allende Presidency". H-Net. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Wilkinson, Tracy (29 August 2023). "Previously classified documents released by U.S. show knowledge of 1973 Chile coup". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Salvador Allende's Last Speech

- "Chilean court confirms Allende suicide - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- "BBC News - Chile inquiry confirms President Allende killed himself". Bbc.co.uk. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- "Admite hija de Allende suicidio de su padre". El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico. 17 August 2003. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Davison, Phil (20 June 2009). "Hortensia Bussi De Allende: Widow of Salvador Allende who helped lead opposition to Chile's military dictatorship". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- "nacion.cl - Restos de Salvador Allende fueron exhumados". Lanacion.cl. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- Associated Press in Santiago (8 July 2016). "Former Chilean army chief charged over 1973 killing of activists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- "Línea de Tiempo – Fundación Salvador Allende". fundacionsalvadorallende.cl. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Hermes H. Benítez & Juan Gonzalo Rocha. "Los verdaderos nombres de Allende" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- "La senadora Allende se equivoca sobre el nacimiento de su padre" (in Spanish). El Mostrador. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Patricio Guzmán, Salvador Allende (film documentary, 2004)

- "José Ramón Allende Padin". Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- "El personaje de hoy: Salvador Allende". 14 July 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Item 0002 - Laura Gossens de Allende, catalogoafudec.udec.cl

- Ancestros, infancia y juventud de Salvador Allende Gossens Archived 22 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, interferencia.cl

- "Cronología de Salvador Allende". Fundación Salvador Allende (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- Tallentire, Mark (3 August 2010). "A hundred years on, Everton face Everton for the first time". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Waitzkin, Howard (2005). "Commentary: Salvador Allende and the birth of Latin American social medicine". International Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (4): 739–741. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh176. PMID 15860637.

- Porter, Dorothy (October 2006). "How Did Social Medicine Evolve, and Where Is It Heading?". PLOS Medicine. 3 (10): e399. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030399. PMC 1621092. PMID 17076552.

- "Famous Freemasons Masonic Presidents". Calodges.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- "Unmasked defamatory libel on Salvador Allende". 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2007. with link to thesis, on the Clarin's website (Spanish version available)

- Salvador Allende by Hedda Garza

- "Telegram protesting against the persecution of Jews in Germany" (PDF) (in Spanish). El Clarín de Chile's. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2005.

- Tedeschi, SK; Brown, TM; Fee, E (2003). "Salvador Allende". Am J Public Health. 93 (12): 2014–5. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.12.2014. PMC 1448142. PMID 14652324.

- Navia, Patricio; Soto Castro, Ignacia (2017). "El efecto de Antonio Zamorano, el Cura de Catapilco, en la derrota de Salvador Allende en la elección presidencial de 1958". Historia (in Spanish). 50 (1).

- "Chile 1964: CIA Covert Support in Frei Election Detailed". The National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "Memorandum for the 303 Committee:Final Report: March 1969 Chilean Congressional Election". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Document 269". U.S. Department of State: Office of the Historian. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Gonzalo Rojas Sanchez; Columna Centenaria, 2008.

- Angell, Alan (1993). "Chile since 1958". In Bethell, Leslie (ed.). Chile since independence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–160, 167. ISBN 0-521-43987-6.

- Tutee, p. 2-3.

- Tutee, p. 3 - 4(till line viii).

- Tutee, p. 6.

- Tutee, p. 7.

- Debray, Régis (1971). The Chilean Revolution: Conversations with Allende. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-71726-5.

- Régis Debray (1972). The Chilean Revolution: Conversations with Allende. New York: Vintage Books.

- "Como Allende destruyo la democracia en Chile" (in Spanish). elcato.org. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- First speech to the Chilean parliament after his election

- "La Unidad Popular" (in Spanish). icarito.latercera.cl. Archived from the original on 7 March 2005., archived 7 March 2005 on the Internet Archive

- Collier & Sater, 1996.

- Peter, Winn (2009). The Chilean Revolution. UNESP. ISBN 9788571399952. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Compagnon, Olivier (2004). "Popular Unity: Chile, 1970-1973" (PDF). In Schlager, Neil (ed.). Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide. Vol. 2. St. James Press. pp. 128–131. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- Mamalakis, Markos (10 August 1973), Income Redistribution in Chile Under Salvador Allende (PDF), Paper presented on 17 August 1973 at the Western Economic Association Meetings in Claremont, California, archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2021, retrieved 31 July 2021

- McGuire, J.W. (2010). Wealth, Health, and Democracy in East Asia and Latin America. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-139-48622-4. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Wright, T.C. (2001). Latin America in the Era of the Cuban Revolution. Praeger. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-275-96705-5. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Henderson, J.D.; Delpar, H.; Brungardt, M.P.; Weldon, R.N. (2000). A Reference Guide to Latin American History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-56324-744-6. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Politics and Ideology in Allende's Chile by Ricardo Israel Zipper.

- "The Socialist-Populist Chilean Experience, 1970–1973" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Collins, Joseph; Lear, John (1995). Chile's Free Market Miracle. Food First. p. 150. ISBN 9780935028638 – via Internet Archive.

- Marcel, M.; Solimano, A. (1993). Developmentalism, Socialism, and Free Market Reform: Three Decades of Income Distribution in Chile. Vol. 1188. Policy Research Department, World Bank. p. 12. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Angell, Alan (1973). "Problems in Allende's Chile". Current History. 64 (378): 57–86. doi:10.1525/curh.1973.64.378.57. ISSN 0011-3530. JSTOR 45314075. S2CID 249804192.

- The Macroeconomics of populism in Latin America by Rüdiger Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards

- The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume VIII, edited by Leslie Bethell.

- A History of Chile, 1808–1994, by Simon Collier and William F. Sater.

- Andrain, C. (2010). Political Change in the Third World. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-415-60129-0. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Mularski, Jedrek. Music, Politics, and Nationalism in Latin America: Chile During the Cold War Era. Amherst: Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1-60497-888-9.

- Shayne, J.D. (2004). The Revolution Question: Feminisms in El Salvador, Chile, and Cuba. Rutgers University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8135-3484-8. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2015.