Samuel Hall (printer)

Samuel Hall (1740-1807), was an Early American publisher and printer, newspaper editor, and an ardent colonial American patriot from Bedford, Massachusetts who was active in this capacity before and during the American Revolution, often printing newspapers and pamphlets in support of American independence. Hall was the founder of The Essex Gazette, the first newspaper published in Salem, Massachusetts in 1768. He often employed his newspaper as a voice supporting colonial grievances over taxation and other actions by the British Parliament that were considered oppressive, and ultimately in support of American independence.

Samuel Hall | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 2, 1740 |

| Died | October 30, 1807 (aged 66) |

| Known for | Establishing the first printing press and newspaper in Salem, 1768 |

Early life and family

Samuel Hall was born on November 2, 1740, in Bedford, Massachusetts. He was the son of Jonathan and Anna (Fowle) Hall. His ancestor, John Hall, settled in Bedford around 1675.[1] As a youth Hall served as an apprentice under his uncle, David Fowle, founder and printer of The New Hampshire Gazette, which is what introduced him to the printing trade.[1][2][3]

Career

Hall moved to Rhode Island and at the age of twenty-two entered into a partnership with the widow Anne Franklin[4][lower-alpha 1] in the publication of the Newport Mercury, beginning with the issue of August 17, 1762. After the death of Mrs. Franklin on April 19, 1763, Hall continued publication of the newspaper paper with success until March 1768, after which he sold it to Solomon Southwick.[1][lower-alpha 2]

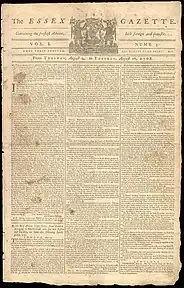

August 9, 1768

In 1767 Hall was persuaded by Captain Richard Derby[lower-alpha 3] to come to Salem, Massachusetts and establish a printing press.[8][9] Receiving financial assistance from Derby, Hall established the first printing house in Salem in 1768,[2][10] and in the same year established its first newspaper, The Essex Gazette,[11] where he announced the purpose of his newspaper, to promote "a due sense of the Rights and Liberties of our Country." Before Hall's printing press arrived in Salem there were only two other printing presses in Massachusetts; One which arrived at Cambridge in 1639, and one at Boston in 1674. Ninety-four years would pass before Hall's printing press would arrive at Salem, making it one of only three printing presses in all of Massachusetts.[9]

In 1774 Hall suffered a serious setback in his printing business when a catastrophic fire swept through Salem and destroyed numerous shops, barns and other dwellings in that city, including Hall's printing shop. With only minutes to spare, Hall was able to save his printing press and some other wares before the fire consumed the shop. Subsequently he moved his printing operation to a large brick building nearby, owned by a Mr. Blaney, which also contained the office of the Salem custom house. With the assistance from friends and neighbors Hall was soon able to continue the printing and publication of the Gazette, giving thanks and tribute to all who gave him help and support in the issue immediately following the fire.[12]

Hall was considered a "staunch patriot", inspired so by the Stamp Act[lower-alpha 4] and the tax on tea.[13] Subsequently the Gazette had strong sympathies to the Whig party and became an able agent to the colonial cause for independence.[1] After three years of publication Hall took on his brother, Ebenezer, as a partner.[2] Their firm was called Samuel & Ebenezer Hall. They remained in Salem until 1775.[2] After the Lexington and Concord, in May 1775, Hall published a full account of the battle, in the Gazette.[14] When the British evacuated Boston in 1776 Hall, under advice of the Massachusetts General Court, and other prominent men of the Whig party, moved into nearby Cambridge with his printing press, and set up his office in Stoughton Hall, at Harvard College, and continued publishing the Gazette, under the new title of The New England Chronicle.[15] Hall's change of location was made "at the Desire of many respectable Gentlemen of the Honourable Provincial Congress", with whom Hall was in high standing.[16]

On February 14, 1776, Hall's brother and partner, Ebenezer, died, leaving a wife and child, and with Samuel publishing the paper on his own again.[17] In April 1776 Hall moved his newspaper to Boston, and continued printing his paper, now simply called The New England Chronicle, with The Essex Gazette removed from the title, and operated there until 1781, until he returned to Salem.[18][19] In June he sold out to Powars & Willis, who renamed the newspaper The Independent Chronicle.[1] He continued printing in Salem until November 1785, after which time he returned to Boston, and established another printing house, along with a book store, in Cornhill.[20] In the Gazette of November 15, 1785, Hall stated his reasons for moving back to Boston, in that the taxes on advertising had cost him much business and that it was recommended by trusted friends that he move from Salem.[21]

Hall took on other printing assignments, which include the printing of The History of Cambridge in 1801, by Abiel Holmes.[22]

Final days and legacy

After Hall relinquished the publication of a newspaper, he printed a few octavo and duodecimo volumes, a variety of small books, for children, illustrated with prints from wood-cuts, and many pamphlets, often containing religious sermons. Historian Isaiah Thomas said of Hall that, "He was a correct printer, and judicious editor; industrious, faithful to his engagements, a respectable citizen, and a firm friend to his country." Hall died on October 30, 1807, at the age of sixty-seven.[20]

See also

Notes

- Ann (Smith) Franklin was married to James Franklin, the older brother of Benjamin Franklin[5]

- Southwick printed some of the first copies of the Declaration of Independence.[6]

- Derby was a successful and principal merchant of the town engaged in foreign trade.[7]

- The Stamp Act had imposed heavy duties on newspapers and official documents of sorts. See: Stamp Act 1765

Citations

- Moody; Malone (ed.), 1932, v. 8, pp. 141

- Thomas, 1874, v. 1, p. 177

- Tapley, 1927, p. 5

- Tapley, 1927, p. 6

- Isaacson, 2004, p. 111

- Crane, 1992, p. 125

- Tapley, 1927, p. 7

- Phillips, 1929, p. 33

- Robbiti, 1948, p. 36

- Robotti, 1948, p. 36

- Buckingham, 1850, v. 1, p. 217

- Tapley, 1927, pp. 25-26

- Tapley, 1927, p. 7

- Hurd (ed.), 1888, p. 118

- Buckingham, 1850, p. 220

- Tapley, 1927, p. 29

- Brigham, 1947, pp. 353

- Thomas, 1874, v. 2, p. 74

- Holmes, 1801, p. 19

- Thomas, 1874, v. 1, p. 178

- Buckingham, 1850, p. 225

- Holmes, 1801

Bibliography

- Brigham, Clarence S. (1947). History and Bibliography of American Newspapers. Vol. I. American Antiquarian Society.

- Buckingham, Joseph Tinker (1850). Specimens of newspaper literature : with personal memoirs, anecdotes, and reminiscences. Vol. I. Boston : Charles C. Little and James Brown.

- —— (1850). Specimens of newspaper literature : with personal memoirs, anecdotes, and reminiscences. Vol. II. Boston : Charles C. Little and James Brown.

- Crane, Elaine Forman (1992). A Dependent People: Newport, Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-1112-8.

- Phillips, James Duncan (1929). The life and times of Richard Derby, merchant of Salem, 1712-1783. Cambridge, Riverside Press.

- Hammett, Charles Edward (1887). A contribution to the bibliography and literature of Newport, R. I.; comprising a list of books published or printed, in Newport. Newport, R.I., C. E. Hammett, jun.

- Holmes, Abiel (1801). The History of Cambridge. Cornhill, Boston, Samuel Hall.

- Hurd, Duane Hamilton, ed. (1888). History of Essex County, Massachusetts, with biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men. Vol. I. Philadelphia, J. W. Lewis & Co.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin, An American Life. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5807-4.

- Moody, Robert E. (1943). Malone, Dumas (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. VIII.

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. - Robotti, Frances Diane (1948). Chronicles of old Salem; a history in miniature. Salem, Mass.

- Tapley, Harriet Silvester (1927). Salem imprints, 1768-1825 : a history of the first fifty years of printing in Salem, Massachusetts, with some account of the bookshops, booksellers, bookbinders and the private libraries. Salem, Mass. : The Essex Institute.

- Thomas, Isaiah (1874). The history of printing in America, with a biography of printers. Vol. I. New York, B. Franklin.

- —— (1874). The history of printing in America, with a biography of printers. Vol. II. New York, B. Franklin.