Samuel Johnson (pamphleteer)

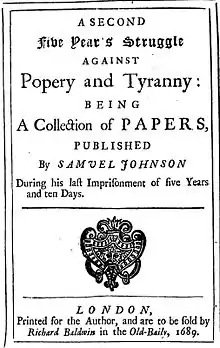

Samuel Johnson (1649–1703) was an English clergyman and political writer, sometimes called "the Whig" to distinguish him from the author and lexicographer of the same name. He is one of the best known pamphlet writers who developed Whig resistance theory.[1]

Life

From a humble background, Samuel Johnson was educated at St. Paul's School and Trinity College, Cambridge, and took orders.[2] He attacked James, Duke of York in Julian the Apostate (1682).

Johnson was illegally deprived of his orders, flogged, and imprisoned. He continued, however, his attacks on the Government by pamphlets, and did much to influence the public mind in favour of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Dryden gave him a place in Absalom and Achitophel as "Benjochanan". After the Revolution he was restored to his orders and received a pension, but considered himself insufficiently rewarded by a deanery, which he declined. He was married for many years and suffered from many illnesses.

The Julian tracts

Johnson's 1682 pamphlet Julian the Apostate was a reply to a sermon A Discourse of the Sovereign Power earlier the same year by George Hickes;[3] it was printed by John Darby.[4] With its sequels, it employed a technique of vilification by the use of parallels in classical literature.[5] In 1683 he followed it with Julian's Arts, but the timing turned out badly, with the revelations of the Rye House Plot, and the pamphlet was held back.[6]

Julian the Apostate met with seven published replies, as well as becoming the target of Oxford sermons. These included pamphlets from Hickes (Jovian), John Bennet (Constantius the Apostate), Edward Meredith, and Thomas Long.[7] He was defended by William Atwood in A Letter of Remarks upon Jovian.[8] William Sherlock backed up Jovian and passive obedience in Case of Resistance (1684).[9]

Whig partisan

.jpg.webp)

Johnson was chaplain to Lord William Russell, a Whig leader, from 1679. Russell directed Johnson's attention to constitutional theory.[10] The result of Johnson's researches was posthumously published in 1769 as A History and Defence of Magna Charta;[11] a second edition appeared in 1772.[12] Russell was later caught up in the Rye House trials. Russell's final speech before his execution was printed, and Johnson, Darby, and Gilbert Burnet were questioned about their involvement in its publication.[13]

References

- Nicholas Phillipson; Quentin Skinner (26 February 1993). Political Discourse in Early Modern Britain. Cambridge University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-521-39242-6. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- "Johnson, Samuel (JHN666S)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Theodor Harmsen. "Hickes, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13203. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Beth Lynch. "Darby, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67087. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hugh Thomas Swedenberg (1972). England in the Restoration and early eighteenth century: essays on culture and society. University of California Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-520-01973-7. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1892). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Melinda S. Zook (1 November 2010). Radical Whigs and Conspiratorial Politics in Late Stuart England. Penn State University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-271-03986-2. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Melinda Zook. "Atwood, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/884. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 52. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Melinda S. Zook (1 November 2010). Radical Whigs and Conspiratorial Politics in Late Stuart England. Penn State Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-271-03986-2. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Samuel Johnson (1769). A History and Defence of Magna Charta. Containing a Copy of the Original Charter at Large, with an English Translation; the Manner of its being Obtained from King John, with its Preservation and Final Establishment in the Succeeding Reigns; with an Introductory Discourse, Containing a Short Account of the Rise and Progress of National Freedom, from the Invasion of Caesar to the Present Times. Also the Liberties which are Confirmed by the Bill of Rights, &c. To which is Added, an Essay on Parliaments, Describing their Origin In England, and the Extraordinary Means by which they have been Lengthened from Half Yearly to Septennial ones. London: Printed for J. Bell, (successor to Mr. Bathoe) at his Circulating-Library, near Exeter-Exchange, in the Strand; S. Bladon, Pater-Noster-Row; and C. Etherington, at York. OCLC 184790025.

- Samuel Johnson (1772). A History and Defence of Magna Charta: Shewing the Manner of its being Obtained from King John, with its Preservation and Final Establishment in the Succeeding Reigns; with an Introductory Discourse, Containing a Short Account of the Rise and Progress of National Freedom, from the Invasion of Cæsar to the Present Times. Also, the Liberties which are Confirmed by the Bill of Rights, &c. To which is Added, an Essay on Parliaments, Describing their Origin in England, and the Extraordinary Means by which they have been Lengthened from Half Yearly to Septennial Ones. By Samuel Johnson, A.M. (2nd ed.). London: Printed for J. Bell, (successor to Mr. Bathoe) at his Circulating-Library, near Exeter-Exchange, in the Strand; S. Bladon, Pater-Noster-Row; and C. Etherington, at York. OCLC 508864662.

- James Rees Jones (1992). Liberty Secured?: Britain Before and After 1688. Stanford University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-8047-1988-9. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.