San Juan Creek

San Juan Creek, also called the San Juan River,[1] is a 29-mile (47 km) long stream in Orange and Riverside Counties, draining a watershed of 133.9 square miles (347 km2).[4][5] Its mainstem begins in the southern Santa Ana Mountains in the Cleveland National Forest. It winds west and south through San Juan Canyon, and is joined by Arroyo Trabuco as it passes through San Juan Capistrano. It flows into the Pacific Ocean at Doheny State Beach. San Juan Canyon provides a major part of the route for California State Route 74 (the Ortega Highway).

| San Juan Creek San Juan River[1] | |

|---|---|

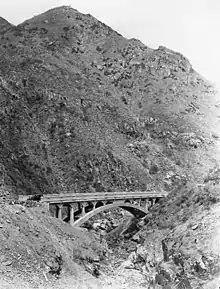

Hikers ford San Juan Creek below the hot springs, February 2008. | |

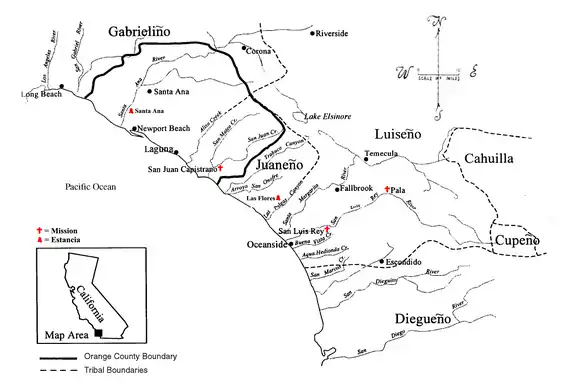

Map of the San Juan Creek watershed | |

| Etymology | Named for Mission San Juan Capistrano by Spanish conquistadors in the 1700s. |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Orange County, Riverside County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | head of San Juan Canyon, at the confluence of Morrell Canyon Creek with Bear Canyon Creek, Santa Ana Mountains |

| • coordinates | 33°36′49″N 117°26′07″W |

| • elevation | 1,690 ft (520 m) |

| Mouth | San Juan Lagoon, Doheny State Beach, Dana Point |

• coordinates | 33°27′42″N 117°41′01″W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 29 mi (47 km) |

| Basin size | 133.9 sq mi (347 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | San Juan Capistrano[2] |

| • average | 26.1 cu ft/s (0.74 m3/s)[3] |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 14,700 cu ft/s (420 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Lucas Canyon Creek, Verdugo Canyon Creek, Trampas Canyon Creek |

| • right | Lion Canyon Creek, Hot Springs Canyon Creek, Cold Spring Canyon Creek, Bell Canyon Creek, Cañada Gobernadora, Cañada Chiquita, Horno Creek, Arroyo Trabuco |

Before Spanish colonization in the 1770s, the San Juan Creek watershed was inhabited by the Acjachemen or Juañeno Native Americans. The Juañeno were named by Spanish missionaries who built Mission San Juan Capistrano on the banks of a stream they named San Juan Creek. The watershed was used mainly for agriculture and ranching until the 1950s when residential suburban development began on a large scale. Since then, the human population has continued to encroach on floodplains of local streams. Flooding in the 20th and 21st centuries has caused considerable property damage in the San Juan watershed.

The San Juan watershed is home to sixteen major native plant communities and hundreds of animal species. However, the watershed is projected to be 48 percent urbanized by 2050. In addition, urban runoff has changed flow patterns in San Juan Creek and introduced pollutants to the river system. Although the main stem of San Juan Creek does not have any major water diversions or dams, some of its tributaries, including Trabuco and Oso Creeks, have been channelized or otherwise heavily modified by urbanization.

Course

San Juan Creek begins high in the Santa Ana Mountains southwest of Lake Elsinore, at the head of the steep and narrow San Juan Canyon, at roughly 1,678 feet (511 m) in elevation where Morrell Canyon Creek, draining the western Elsinore Mountains and southernmost Santa Ana Mountains, has its confluence with Bear Canyon Creek. From there, it flows steeply down a rocky gorge over rapids and waterfalls. San Juan Canyon forms the mountain pass for California State Route 74 (the Ortega Highway), which connects San Juan Capistrano to Lake Elsinore and the Inland Empire. San Juan Falls, a 15-foot (4.6 m) cascade, and the 30-foot (9.1 m) Ortega Falls are located along the headwaters of the creek.[6] The creek then flows generally southwest through a canyon, receiving Hot Springs Creek and Cold Springs Creek from the right, and Lucas Canyon Creek from the left.[7][8][9]

At Caspers Wilderness Park, the San Juan Canyon opens up into a fairly wide valley in the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains. This reach of San Juan Creek is underlain by thick alluvial deposits and is still used for farming and grazing.[10] It is joined by Bell Canyon from the right,[11][12] and Verdugo Canyon Creek from the left. Trampas Canyon enters from the left and Cañada Gobernadora and Cañada Chiquita enter from the right. The creek flows through residential Rancho Mission Viejo, crosses under Interstate 5, and enters a concrete flood control channel, turning south and receiving El Horno Creek on the right.[13] It receives its largest tributary, Arroyo Trabuco, from the right, then flows south toward the Pacific Ocean. The creek forms a fresh water lagoon at the northern end of Doheny State Beach, which overflows into Capistrano Bay during periods of high flow.[7][8][9][14]

Tributaries

All direct tributaries of San Juan Creek, from mouth to source, are listed. The list also includes streams that join major tributaries.

|

|

Bell Creek, the second largest tributary of San Juan Creek, flowing through Caspers Wilderness Park

|

Geology

The San Juan Creek watershed is crossed by a complex network of seismic fault zones, with streams tending to form canyons along fault traces. The Cristianitos fault (Cristianitos) runs northeast-southwest along Oso Creek, passing offshore 7 miles (11 km) south of the mouth of San Juan Creek. The Mission Viejo fault zone parallels the Cristianitos but ends much farther south, in San Diego County. The first recorded earthquake in the area partially destroyed Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1812 (which had been built only six years before), killing forty people in the adobe chapel when it collapsed. Other major quakes occurred in 1862, 1933 and 1938.[15][7]

Soils in the San Juan watershed are mostly sedimentary rock and are highly erosive, resulting in large alluvial deposits along floodplains. Soil types in the San Juan watershed can be divided into the Metz-San Emigdio, Sorrento-Mocho, Myford, Alo-Bosanko, Cieneba-Anaheim-Soper, and Friant-Cieneba-Exchequer associations, in order from low to high elevations. Steep hills in the San Juan watershed are prone to collapse during heavy rainfall or seismic activity.[7][16]

Over the past 1.2 million years the uplift of the San Joaquin Hills, a small coastal mountain range generally following the Pacific coast of Orange County, created a physical barrier for streams flowing off the Santa Ana Mountains. Climate change during the Ice Ages periodically made Southern California much wetter, most recently during the Wisconsinian Glaciation (70,000 to 10,000 years ago), when the area was home to a temperate rainforest climate that would receive rainfall in excess of 80 inches (2,000 mm) per year. The increase in water flow in San Juan Creek allowed it to maintain its course as an antecedent stream, rather than being diverted to the east or west.[17]

Hydrology and groundwater

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) measured the discharge of San Juan Creek in the city of San Juan Capistrano for two periods, from 1928 to 1969 and from 1969 to 1985. Stream flows for the earlier period are considerably different from the later period due to increased volumes of urban runoff. For 1928–1969, the average discharge was 14.3 cubic feet per second (0.40 m3/s),[18] and the peak flow was 22,400 cubic feet per second (630 m3/s) on February 25, 1969.[19] During the 1969–1985 period, the average flow was 26.1 cubic feet per second (0.74 m3/s),[20] and a peak flow of 14,700 cubic feet per second (420 m3/s) was recorded on March 4, 1978.[21] After 1985, the USGS stopped measuring discharge but continues to monitor water level in real-time at the La Novia Street bridge.[22] According to the city of San Juan Capistrano, the largest flood of record occurred on January 11, 2005 with an estimated discharge of 33,650 cubic feet per second (953 m3/s).[23]

According to the California State Water Resources Control Board (1977) the San Juan Creek Groundwater Basin has a total volume of roughly 900,000 acre-feet (1.1×109 m3). Natural groundwater recharge in the San Juan basin is estimated at 160,000 acre-feet (200,000,000 m3) per year. This amount has been reduced due to extensive urbanization of the lower watershed which results in more water running off to the Pacific Ocean. However, water from irrigation run-off and other human activities is responsible for recharging an additional 37,500 acre-feet (46,300,000 m3) per year. The Christianitos and Mission Viejo fault zones split the watershed into distinct "Upper" and "Lower" groundwater basins. The groundwater mostly lies in alluvium, which ranges from a depth of 200 feet (61 m) in the lower elevations to almost none in the high elevations.[7] Groundwater in this basin at the San Juan Capistrano reach is considered of high quality.[24]

Although San Juan Creek contains water for most of the year, it is highly seasonal, with strong flows during the wettest months of January through March, and shrinking to a trickle during the other months. In poor rain years, the stream can often dry up completely in its lower reaches. The total natural (unimpaired) surface outflow from the San Juan basin into the Pacific is estimated at 5,200 acre-feet (6,400,000 m3) per year. Agricultural and urban runoff significantly increased the average outflow, to 7,800 acre-feet (9,600,000 m3) as of 1993. The maximum annual outflow is 9,000 acre-feet (11,000,000 m3). Although the use of local surface water and groundwater is increasing, local groundwater levels have not been affected significantly by human use, due to the relatively high natural recharge rate.[7]

Due to the lower amount of urbanization in the San Juan watershed as compared with other watersheds in the county, the 100-year flood inundation risk is also significantly lower than in other parts of Orange County. It has been calculated that a 100-year flood in the watershed would only affect a roughly 0.5 mi (0.80 km) wide area for the lower reaches of San Juan Creek inside San Juan Capistrano, while for Arroyo Trabuco, only a 0.2 mi (0.32 km) wide area would be affected, mainly due to considerable entrenchment of the river bed.[25] However, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers considers many levees in the San Juan Capistrano area to be inadequate for handling the 100-year flood, and that such a flood would cause $149 million of property damage.[7]

Watershed

The San Juan Creek watershed covers 133.9-square-mile (347 km2) in south Orange County and a very small portion of Riverside County. The Santa Ana Mountains occupy most of the north, east and south parts watershed, while the San Joaquin Hills border the watershed on the southwest. Along with San Juan Creek, the two largest tributaries – Trabuco and Bell Creeks – both originate in the Santa Ana Mountains. Although more than half of the watershed is undeveloped land, it also includes parts of the cities of Dana Point, Laguna Hills, Laguna Niguel, Mission Viejo, Rancho Santa Margarita, San Clemente, San Juan Capistrano, and the unincorporated communities of Trabuco Canyon (near Rancho Santa Margarita) and Rancho Mission Viejo (east of San Juan).

There are four main alluvial river valleys in the watershed. The San Juan Creek valley occupies the south portion of the watershed; the heavily urbanized lower (southwest) portion is located in the cities of San Juan Capistrano and Dana Point, while the largely rural (northeast) portion extends well into the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains. The Arroyo Trabuco valley forms a large alluvial plain called "Plano Trabuco" in the north part of the watershed (part of suburban Rancho Santa Margarita). The Oso Creek valley is narrower, running south through Mission Viejo and Laguna Hills, and is mostly urbanized. The Bell Creek valley is the least urbanized of the four, being mostly located in the Cleveland National Forest, Starr Ranch Preserve and Caspers Wilderness Park. There are 19 other major tributaries in the watershed.[11][26]

The California Department of Water Resources includes San Juan Creek in the 500-square-mile (1,300 km2) San Juan Hydrologic Unit, which includes the coastal watersheds of Aliso Creek, Salt Creek, Prima Deshecha Cañada, Segunda Deshecha Cañada, and San Mateo Creek, which share a similar range of elevations and climate. Elevation in the Hydrologic Unit ranges from sea level to 5,700 feet (1,700 m) at Santiago Peak (the headwater of Holy Jim Creek, a tributary of Arroyo Trabuco). The climate is Mediterranean, with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. Almost all the precipitation occurs between October and April; the average rainfall is 12 to 16 inches (300 to 410 mm), although mountain areas often receive higher amounts.[7][27] San Juan Creek receives extra runoff from agriculture, urban areas, and other human sources, resulting in unnatural dry season flows[26] that carry trash, heavy metals, oils, pesticides and fertilizer into the creek. The heaviest source of pollution is Oso Creek. Michael Hazzard, a Southern California environmentalist, said after diving into Upper Oso Creek Reservoir: "I spent three days diving to retrieve an outboard motor and my skin broke out in hives and boils and my gallbladder suffered and I later had six operations over a 21⁄2-year period."[28]

Ecology

San Juan Creek was originally rich in riparian zones and other types habitat in both its upper and lower watershed, with wetlands totaling over 300 acres (1.2 km2) historically in the lower reaches, before urban development began in the 1950s. Only 0.3 percent of those wetlands remain.[16] Recent efforts of stream conservation have been in the planning stage including habitat conservation plan work.[29]

There are sixteen prominent vegetation zones in the San Juan watershed, which include riparian vegetation, montane woodlands, coastal sage scrub and chaparral. Riparian vegetation is found along the banks of free-flowing streams with a measurable flow for at least several months out of the year. These include most of San Juan Creek, upper Arroyo Trabuco, Cañada Gobernadora, Bell Canyon, and other headwater streams, as well as scattered patches along Oso and El Horno creeks. Forests are present at high elevations, and also occur in close proximity to waterways. Coastal sage scrub is found on south-facing hillsides, while chaparral is found on higher-elevation hillsides and mesas. There are also a number of rare plant communities along rock outcroppings and vernal pools. However, introduced plant species, such as giant reed, castor bean, and tobacco tree, are rapidly spreading along streams.[7][30] Giant reed has taken over huge areas of wetlands, swamps and riparian zones along the creek and its tributaries, although in recent years the county has taken steps toward eradicating it from San Juan Creek and other nearby streams.[31]

Historically, the San Juan watershed supported up to 12 invertebrate species, 5 fish species, 12 amphibian species, 35 reptile species, 143 bird species, and 42 mammal species, which benefited from the diverse vegetation communities present. Some streams and ponds host federally listed endangered/threatened species such as tidewater goby, fairy shrimp, and California red-legged frog. Federally listed bird species include least Bell's vireo, California gnatcatcher, California least tern, and southwestern willow flycatcher. Other listed species include Pacific pocket mouse and Quino checkerspot butterfly. As urbanization continues to increase in the San Juan watershed, most sensitive species have been pushed back to the foothills, mountains, and agricultural/ranching areas of the watershed.[7][30]

In 1987, just five bird species were confirmed in the watershed, while for fish, benthic invertebrates, and certain insects there were no confirmed observations, in part due to insufficient site coverage.

Historic accounts suggest that San Juan Creek provided habitat for steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus) in many historic accounts. However, pollution and competition from introduced sport fishes such as bluegill and striped bass[30] have extirpated steelhead in the creek. Bacteria levels in San Juan Creek exceed state standards by 93 percent.[32] The loss of riparian habitat along the lower 2.7 miles (4.3 km) of San Juan Creek and much of Trabuco and Oso Creeks due to channelization has also reduced steelhead habitat. However, in 2003 the California Department of Fish and Game reported three sightings of steelhead in a large stream pool along Trabuco Creek, immediately downstream of a drop structure that channels the creek beneath Interstate 5.[33] In response, the Department of Fish and Game lobbied Caltrans to build a fish ladder at the structure, but it has not yet been implemented, due to concerns about structural stability of the I-5 bridge and the presence of a nearby natural gas pipeline.[34][35]

History

Indigenous peoples

Before the 18th century, the San Juan Creek watershed was mostly Acjachemen territory, which extended from Aliso Creek in the north to San Mateo Creek in the south, a distance of roughly 35 miles (56 km). Most of the population lived along the two major streams in the area, San Juan and San Mateo Creeks, as well as Arroyo Trabuco.[36]

The Acjachemen lived in villages along San Juan Creek, including villages on the main stem of San Juan Creek, the largest being Putiidhem, which was the mother village of the people, as well as Sajavit and Piwiva, while Huumai was located on the tributary Cañada Gobernadora.[37][38] The Acjachemen diet usually consisted of fruits, acorns, grains, and some meat, while they practiced little agriculture. Shell middens indicate that they also harvested shellfish from the coast. Native peoples in this area are not known to have built permanent structures in this area or significantly influenced the natural environment.[7]

Spanish arrival

The first European land exploration of Alta California, the Spanish Portolá expedition, passed this way on its way north, camping at San Juan Creek on July 23, 1769. Franciscan missionary Juan Crespi noted in his diary: "...we came to a very pleasant green valley, full of willows, alders, live oaks, and other trees not known to us. It has a large arroyo, which at the point where we crossed it carried a good stream of fresh and good water, which, after running a little way, formed in pools in some large patches of tules."[39] On the return journey to San Diego, the party used the campsite again, on January 20.

In 1776, Father Junípero Serra founded Mission San Juan Capistrano on a site close to the creek (possibly near the Cañada Gobernadora confluence), and the creek was named after the mission. The first site was abandoned due to lack of water,[15] although some historical accounts suggest the creek once had a perennial flow.[16] The mission was moved to a second site in present-day San Juan Capistrano, where it still stands. The Spanish referred to the Acjachemem as the Juañeno. The Spanish made the first recorded anthropogenic changes to hydrology in the San Juan watershed, which included excavating irrigation channels, diverting water from streams, and channelizing and changing course of streams.[7] Grazing animals introduced by Europeans, mainly cattle (and later sheep, after a drought decimated the local cattle ranching industry), consumed native grasses and left hillsides exposed and prone to erosion.[7]

The origin of the name of Arroyo Trabuco (Spanish: "Blunderbuss Creek", literally) stems from the Gaspar de Portolà expedition of 1769, during which a soldier lost a blunderbuss ("trabuco"), and the name became associated with the creek after that point.[40][41] The origin of the name of Oso Creek (Spanish: "Bear Creek") is not known. Many of the creeks in the watershed have names of Spanish origin, which were most likely named by the Spanish conquistadors a long time before the area was annexed by the United States.[7]

Before urban development, the damage caused by overgrazing during the Spanish period was still considered capable of recovery. However, the completion of Interstate 5 through the middle of the San Juan Creek watershed in the 1950s transformed the area into a bedroom community for Los Angeles and permanently erased many remaining grassland, meadow and riparian zones. The percent of urbanized land increased from 3 percent in 1964 to 18 percent in 1988. In the 1990s, the watershed was 32 percent urbanized. With continuing development in east San Juan Capistrano and Rancho Mission Viejo, the projected growth by 2050 is 50 percent.[7]

20th century to present

In the late 1960s, Dana Point Harbor was constructed adjacent to the mouth of San Juan Creek.[42] The breakwater prevented the occurrence of a large surf break phenomenon, colloquially known as "Killer Dana", in the bay. When Killer Dana disappeared, water circulation in the bay decreased. As polluted runoff from San Juan Creek continues to flow into the bay, it is trapped for extended periods of time. At Doheny State Beach, 850,000 annual visitors are exposed to potential health risks from high bacteria levels in the water.[43]

During floods in the 1990s, an almost sheer 30-foot (9.1 m) waterfall appeared on Arroyo Trabuco in northern San Juan Capistrano, threatening the foundations of a railroad bridge. The drop required quick reinforcement with grouted riprap. With an average gradient of 29 percent it has become a major barrier to migrating fish and other riverine organisms, and thus isolates aquatic environments in upper Arroyo Trabuco from the rest of the San Juan watershed.[44]

In 1996, severe floods caused by heavy rainstorms in the San Juan watershed caused San Juan Creek to overflow, destroying long sections of the concrete river banks near their confluence. The damage was attributed to severe erosion at the base which caused the concrete to lose support and crumble. A nearby residential community was threatened, but the floods receded before the levee collapsed and no serious harm was done. The failed sections were repaired with grouted riprap.[30][23]

In early 2005, even more severe flooding impacted the San Juan watershed, with an all-time highest flow of 33,650 cubic feet per second (953 m3/s) recorded on January 11. Although the floods did not exceed the San Juan Creek channel capacity of 58,800 cubic feet per second (1,670 m3/s), the west levee of the channel inside San Juan Capistrano nearly failed.[23]

Also in 2005, pumps were installed on Tick and Dove Creeks (tributaries of Bell Canyon) to remove urban runoff from 1,100-acre (450 ha) of residential areas in eastern Rancho Santa Margarita. The pumps remove excess flow and divert it to storage basins for later use as reclaimed irrigation water.[12]

Between 2009 and 2013, extensive levee repairs were conducted along lower San Juan Creek. Construction closed the popular San Juan Creek bikeway for two years, inciting protests from many area residents who are frequent users of the path.[45]

River modifications

Although the San Juan Creek watershed is less heavily developed than other coastal Orange County watersheds, extensive works have been constructed to control floods, reduce erosion, and provide reclaimed water for irrigation. A growing amount of urban runoff flows into the creek and its tributaries, creating a dry season "nuisance flow". Historically, only San Juan Creek and Arroyo Trabuco were known to contain water for most or all of the year.[16] Oso Creek was formerly a seasonal stream, but it now has a permanent flow due to urban runoff.[46] Runoff has caused Doheny Beach to rank in the ten most polluted beaches of California.[43]

The Upper Oso Reservoir and Lake Mission Viejo, both on Oso Creek, are the largest impoundments in the watershed, holding about 7,500 acre-feet (9,300,000 m3) combined. While Lake Mission Viejo was built solely for recreation, the 115-acre (0.47 km2) Upper Oso Reservoir collects Oso Creek water and diverts it for irrigation use. The reservoir is occasionally used by air tankers to combat wildfires in the Cleveland National Forest.[47] The Santa Margarita Water District is currently proposing a new 5,000-acre-foot (6,200,000 m3) reservoir in Verdugo Canyon, another tributary of San Juan Creek, to collect and store reclaimed water.

The lower 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of San Juan Creek are channelized between levees, from a point immediately upstream of the Interstate 5 bridge to Doheny Beach. Arroyo Trabuco is only channelized for several hundred yards above its confluence with San Juan Creek. Oso Creek is the most heavily modified, flowing in an artificial channel for almost its entire length. Bell Creek and other eastern tributaries have retained their natural characteristics. The USACE describes the San Juan and Arroyo Trabuco levees as providing a "fairly high level of protection currently",[7] though flooding in 1996 and 2005 caused significant damage. As a result, failure scenarios of levees in the San Juan watershed have been extensively studied.[7][30] To protect against future flooding, work has begun on a new west-bank levee replacement to be finished in 2013.[45]

A few check dams exist on small upper tributaries of San Juan Creek, mostly inside the Cleveland National Forest. A larger gabion-type dam is located on the middle part of San Juan Creek near the Cañada Gobernadora. Although the dam has silted in and is no longer used for water storage, its roughly 3-to-4-foot (0.91 to 1.22 m) drop still poses a problem for migrating steelhead. There are a few water diversion weirs that exist on San Juan tributary streams to divert water for irrigation, ranching and limited municipal uses, but due to limited flows and polluted water, the usefulness of these structures are limited.[44]

A number of drop structures (small dams used to control water velocity and erosion) exist on tributaries of San Juan Creek. On Arroyo Trabuco, there are eight drop structures, mostly built of riprap. The largest are a 30-foot (9.1 m) cascade immediately downstream of a Metrolink bridge, and a concrete drop structure at the terminus of a culvert that crosses underneath Interstate 5.[48] There are also seven drop structures on Oso Creek, mostly built of riprap.[48] There are no such specifically constructed structures on San Juan Creek itself.[48]

List of crossings

This is a list of major crossings of San Juan Creek, proceeding upstream of the mouth.[7][49]

|

|

References

- "San Juan Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- "USGS Gage #11046550 on San Juan Creek at San Juan Capistrano, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1969–1985. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- "USGS Gage #11046550 on San Juan Creek at San Juan Capistrano, CA". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1969–1985. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- 7.5 Minute Quadrangle Map, U.S. Geological Survey, San Juan Capistrano, 1968, photorevised 1981

- "Introduction to San Juan Creek Watershed". Watershed and Coastal Resources Division of Orange County. www.ocwatersheds.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13.

- Shaffer, p. 379-380

- "San Juan Watershed Watershed Management Study" (PDF). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. www.ocwatersheds.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-13. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- "San Juan Creek Watershed and Elevation Ranges (Map)". Watershed and Coastal Resources Division of Orange County. www.ocwatersheds.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Map of San Juan Creek (Map). Cartography by NAVTEQ. Google Maps. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- "San Juan Creek Watershed – Land Use". Watershed and Coastal Resources Division of Orange County. www.ocwatersheds.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- "San Juan Creek Watershed Management Study" (PDF). Watershed and Coastal Resources Division of Orange County. August 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-13. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Riparian Habitat Enhancement and Monitoring". Audubon – California Starr Ranch Sanctuary. www.starrranch.org. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Section 2.2: Physical Environment" (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- "General Plan 13: Floodplain Management Element" (PDF). City of San Juan Capistrano. 14 December 1999. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- "Mission San Juan Capistrano". The San Juan Capistrano Historical Society. sjchistoricalsociety.com. Archived from the original on 2007-07-18. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- "San Juan Creek". California Resources Agency. ceres.ca.gov. 2 December 1997. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Colburn, Ivan P. "The Role of Antecedent Rivers in Shaping the Orange/Los Angeles Coastal Plain" (PDF). California State University Los Angeles, Department of Geology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- "USGS Gage #11046500 San Juan Creek near San Juan Capistrano, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1928–1969. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- "USGS Gage #11046500 San Juan Creek near San Juan Capistrano, CA: Peak-Flow Data". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1928–1969. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- "USGS Gage #11046550 San Juan Creek at San Juan Capistrano, CA: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1969–1985. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- "USGS Gage #11046550 San Juan Creek at San Juan Capistrano, CA: Peak-Flow Data". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1969–1985. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- "USGS Gage #11046530 San Juan Creek at La Novia St Bridge at San Juan Capistrano, CA: Current Conditions". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- "Agenda Item". County of Orange, Resources Development and Management Department. City of San Juan Capistrano. 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Earth Metrics Incorporated, Phase I Environmental Site Assessment for Rancho San Juan Capistrano, bounded by San Juan Creek Road, Paseo Ranchero and Camino San Jose Road, San Juan Capistrano, California, January 4, 1990

- Technical Background Report, General Plan Update – City of San Juan Capistrano, August 1999

- "San Juan Hydrologic Unit Profile". California Coastal Conservancy. Southern California Coastal Watersheds Inventory. Archived from the original on 2009-05-30. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program (SWAMP) Report on the San Juan Hydrologic Unit" (PDF). California State Water Resources Control Board. Jul 2007. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- Reyes, David (4 January 2004). "He Puts Clean Water First". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Jae Chung, San Juan Creek/San Mateo Creek SAMP, 27 December 2007

- "San Juan Creek Watershed Management Plan" (PDF). Watershed and Coastal Resources Division of Orange County. www.ocwatershed.com. September 2002. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- "Mitigation Concept" (PDF). County of Orange. www.ocplanning.net. 2004. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- "Beach Buddies and Beach Bums: Testing the Waters 2006. NRDC's Annual Guide to Water Quality at Vacation Beaches" (PDF). National Resources Defense Council. www.nrdc.org. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- Weikel, Dan (2003-12-24). "Endangered Steelhead Trout Likely Making A Comeback In O.C. Creek". The Los Angeles Times. articles.latimes.com. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- Brennan, Pat. "Big fish, bigger plans: A large steelhead trout tries to swim up San Juan Creek – and one day, the species might succeed". OC Register. www.ocregister.com. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- Weikel, Dan (2003-12-24). "Endangered Steelhead Trout Likely Making A Comeback In O.C. Creek". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- "Native American History (Juañeno)". The San Onofre Foundation. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- O'Neil, Stephen; Evans, Nancy H. (1980). "Notes on Historical Juaneno Villages and Geographical Features". UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 2 (2): 226–232.

- Koerper, Henry; Mason, Roger; Peterson, Mark (2002). Catalysts to complexity : late Holocene societies of the California coast. Jon Erlandson, Terry L. Jones, Jeanne E. Arnold, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA. pp. 64–66, 79. ISBN 978-1-938770-67-8. OCLC 745176510.

- Bolton, Herbert E. (1927). Fray Juan Crespi: Missionary Explorer on the Pacific Coast, 1769–1774. HathiTrust Digital Library. pp. 136–137, 270–271. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Trabuco Canyon History". Trabuco Canyon, California. www.trabucocanyon.org. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- "Trabuco Canyon, California". Orange County City Guide. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- "History of Dana Point". www.bridgeguys.com. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- "LA County beaches most polluted in state". The Daily Bruin. dailybruin.ucla.edu. 26 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- Katagi, Wendy; Johnson, Theodore; Sutherland, George (2008). "Steelhead Recovery in the San Juan and Trabuco Creeks Watershed". Trout Unlimited South Coast Chapter. American Society of Civil Engineers.

- "Creek levee construction to block bicycle route for 2 more years". OC Register. 6 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Oso Creek/Hydrology". Laguna Niguel Amended Gateway Specific Plan. City of Laguna Niguel. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Upper Oso Reservoir Dam". WayMarking.com. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- "OC Flood Channel Grade Control Structure Inventory". Orange County Flood Control Division. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- "National Bridge Inventory". Retrieved 2009-06-11.

Works cited

- Shaffer, Chris. The Definitive Guide to the Waterfalls of Southern and Central California. Shafdog Publications, 2005.